- Piazza dei Miracoli

-

Piazza del Duomo, Pisa * UNESCO World Heritage Site

Country Italy Type Cultural Criteria i, ii, iv, vi Reference 395 Region ** Europe Inscription history Inscription 1987 (11th Session) * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List

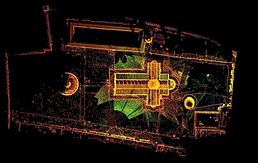

** Region as classified by UNESCO Aerial perspective on Piazza del Duomo, created with laser scan data from a CyArk/University of Ferrara partnership. The Cathedral is cruciform in plan and is situated on an east-west axis with the primary apse facing east.

Aerial perspective on Piazza del Duomo, created with laser scan data from a CyArk/University of Ferrara partnership. The Cathedral is cruciform in plan and is situated on an east-west axis with the primary apse facing east.

The Piazza del Duomo ("Cathedral Square") is a wide, walled area at the heart of the city of Pisa, Tuscany, Italy, recognized as one of the main centers for medieval art in the world. Partly paved and partly grassed, it is dominated by four great religious edifices: the Duomo (cathedral), the Campanile (the cathedral's free standing bell tower), the Baptistry and the Camposanto.

It is otherwise known as Piazza dei Miracoli ("Square of Miracles"). This name was created by the Italian writer and poet Gabriele d'Annunzio who, in his novel Forse che si forse che no (1910) described the square in this way:

L’Ardea roteò nel cielo di Cristo, sul prato dei Miracoli.

which means: "The Ardea rotated over the sky of Christ, over the meadow of Miracles."

Often people tend to mistake the term with Campo dei Miracoli ("Field of Miracles"). This one is a fictional magical field in the book Pinocchio, where a gold coin seed will grow a money tree.[1]

In 1987 the whole square was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Contents

Duomo

The heart of the Piazza del Duomo is, obviously, the Duomo, the medieval cathedral, entitled to Santa Maria Assunta (St. Mary of the Assumption). This is a five-naved cathedral with a three-naved transept. The church is known also as the Primatial, the archbishop of Pisa being a Primate since 1092.

Construction was begun in 1064 by the architect Busketo, and set the model for the distinctive Pisan Romanesque style of architecture. The mosaics of the interior, as well as the pointed arches, show a strong Byzantine influence.

The façade, of grey marble and white stone set with discs of coloured marble, was built by a master named Rainaldo, as indicated by an inscription above the middle door: Rainaldus prudens operator.

The massive bronze main doors were made in the workshops of Giambologna, replacing the original doors destroyed in a fire in 1595. The central door was in bronze and made around 1180 by Bonanno Pisano, while the other two were probably in wood. However worshippers never used the façade doors to enter, instead entering by way of the Porta di San Ranieri (St. Ranieri's Door), in front of the Leaning Tower, made in around 1180 by Bonanno Pisano.

Above the doors there are four rows of open galleries with, on top, statues of Madonna with Child and, on the corners, the Four evangelists.

Also in the façade we can find the tomb of Busketo (on the left side) and an inscription about the foundation of the Cathedral and the victorious battle against Saracens.

At the east end of the exterior, high on a column rising from the gable is a modern replica of the Pisa Griffin, the largest Islamic metal sculpture known, the original of which was placed there probably in the 11th or 12th century, and is now in the Cathedral Museum.

The interior is faced with black and white marble and has a gilded ceiling and a frescoed dome. It was largely redecorated after a fire in 1595, which destroyed most of the medieval art works.

Fortunately, the impressive mosaic, in the apse, of Christ in Majesty, flanked by the Blessed Virgin and St. John the Evangelist, survived the fire. It evokes the mosaics in the church of Monreale, Sicily. Although it is said that the mosaic was done by Cimabue, only the head of St. John was done by the artist in 1302 and was his last work, since he died in Pisa in the same year. The cupola, at the intersection of the nave and the transept, was decorated by Riminaldi showing the ascension of the Blessed Virgin.

Galileo is believed to have formulated his theory about the movement of a pendulum by watching the swinging of the incense lamp (not the present one) hanging from the ceiling of the nave. That lamp, smaller and simpler than the present one, it is now kept in the Camposanto, in the Aulla chapel.

The impressive granite Corinthian columns between the nave and the aisle came originally from the mosque of Palermo, captured by the Pisans in 1063.

The coffer ceiling of the nave was replaced after the fire of 1595. The present gold-decorated ceiling carries the coat of arms of the Medici.

The elaborately carved pulpit (1302–1310), which also survived the fire, was made by Giovanni Pisano and is one the masterworks of medieval sculpture. It was packed away during the redecoration and was not rediscovered and re-erected until 1926. The pulpit is supported by plain columns (two of which mounted on lions sculptures) on one side and by caryatids and a telamon on the other: the latter represent St. Michael, the Evangelists, the four cardinal virtues flanking the Church, and a bold, naturalistic depiction of a naked Hercules. A central plinth with the liberal arts supports the four theological virtues.

The present day reconstruction of the pulpit is not the correct one. Now it lies not in the same original position, that was nearer the main altar, and the disposition of the columns and the panels are not the original ones. Also the original stairs (maybe in marble) were lost.

The upper part has nine panels dramatic showing scenes from the New Testament, carved in white marble with a chiaroscuro effect and separated by figures of prophets: Annunciation, Massacre of the Innocents, Nativity, Adoration of the Magi, Flight into Egypt, Crucifixion, and two panels of the Last Judgement.

The church also contains the bones of St Ranieri, Pisa's patron saint, and the tomb of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII, carved by Tino da Camaino in 1315. That tomb, originally in the apse just behind the main altar, was disassembled and changed position many times during the years for political reasons. At last the sarcophagus is still in the Cathedral, but some of the statues were put in the Camposanto or in the top of the façade of the church. The original statues now are in the Museum of the Opera del Duomo.

Pope Gregory VIII was also buried in the cathedral. The fire in 1595 destroyed his tomb.

The Cathedral has a prominent role in determining the beginning of the Pisan New Year. Between the tenth century and 1749, when the Tuscan calendar was reformed, Pisa used its own calendar, in which the first day of the year on March 25, which is the day of the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary. The Pisan New Year begins 9 months before the ordinary one. The exact moment is determined by a ray of sun that, through a window on the left side, hit a shelf egg-shaped on the right side, just above the pulpit by Giovanni Pisano. This occurs at noon.

In the Cathedral also can be found some relics brought during the Crusades: the remains of three Saints (Abibo, Gamaliel and Nicodemus) and a vase that it is said to be one of the jars of Cana.

The building, as have several in Pisa, has tilted slightly since its construction.

Baptistery

The Baptistery See also: Baptistry (Pisa)

See also: Baptistry (Pisa)The Baptistery, dedicated to St. John the Baptist, stands opposite the west end of the Duomo. The round Romanesque building was begun in the mid 12th century: 1153 Mense August fundata fuit haec ("In the month of August 1153 was set up here..."). It was built in Romanesque style by an architect known as Diotisalvi ("God Save You"), who worked also in the church of the Holy Sepulchre in the city. His name is mentioned on a pillar inside, as Diotosalvi magister. the construction was not, however, finished until the 14th century, when the loggia, the top storey and the dome were added in Gothic style by Nicola Pisano and Giovanni Pisano.

It is the largest baptistery in Italy. Its circumference measures 107.25 m. Taking into account the statue of St. John the Baptist (attributed to Turino di Sano) on top of the dome, it is even a few centimetres higher than the Leaning Tower.

The portal, facing the façade of the cathedral, is flanked by two classical columns, while the inner jambs are executed in Byzantine style. The lintel is divided in two tiers. The lower one depicts several episodes in the life of St. John the Baptist, while the upper one shows Christ between the Madonna and St John the Baptist, flanked by angels and the evangelists.

The immensity of the interior is overwhelming, but it is surprisingly plain and lacks decoration. It has notable acoustics also.

The octagonal font at the centre dates from 1246 and was made by Guido Bigarelli da Como. The bronze sculpture of St. John the Baptist at the centre of the font, is a remarkable work by Italo Griselli.

The pulpit was sculpted between 1255-1260 by Nicola Pisano, father of Giovanni Pisano, the artist who produced the pulpit in the Duomo. The scenes on the pulpit, and especially the classical form of the naked Hercules, show at best Nicola Pisano's qualities as the most important precursor of Italian renaissance sculpture by reinstating antique representations.[2] Therefore, surveys of the Italian Renaissance usually begin with the year 1260, the year that Nicola Pisano dated this pulpit.[3]

Bell Tower

See also: Leaning Tower of PisaThe campanile (bell tower) is located behind the cathedral. The last of the three major buildings on the piazza to be built, construction of the bell tower began in 1173 and took place in three stages over the course of 177 years, with the bell-chamber only added in 1372. Five years after construction began, when the building had reached the third floor level, the weak subsoil and poor foundation led to the building sinking on its south side. The building was left for a century, which allowed the subsoil to stabilise itself and prevented the building from collapsing. In 1272, to adjust the lean of the building, when construction resumed, the upper floors were built with one side taller than the other. The seventh and final floor was added in 1319. By the time the building was completed, the lean was approximately 1 degree, or 2.5 feet (80 cm) from vertical. At its greatest, measured prior to 1990, the lean measured approximately 5.5 degrees. As of 2010, this has been reduced to approximately 4 degrees.

The tower stands approximately 60m high, and was built to accommodate a total of seven main bells, cast to the musical scale:

- 1st bell (clockwise): L'Assunta, cast in 1654 by Giovanni Pietro Orlandi, weight 3,620 kg (7,981 lb)

- 2nd bell: Il Crocifisso, cast in 1572 by Vincenzo Possenti, weight 2,462 kg (5,428 lb)

- 3rd bell: San Ranieri, cast in 1719-1721 by Giovanni Andrea Moreni, weight 1,448 kg (3,192 lb)

- 4th bell: La Terza (1st small one), cast in 1473, weight 300 kg (661 lb)

- 5th bell: La Pasquereccia or La Giustizia, cast in 1262 by Lotteringo, weight 1,014 kg (2,235 lb)

- 6th bell: Il Vespruccio (2nd small one), cast in the 14th century and again in 1501 by Nicola di Jacopo, weight 1,000 kg (2,205 lb)

- 7th bell: Dal Pozzo, cast in 1606 and again in 2004, weight 652 kg (1,437 lb)[4]

- Number of steps to the top: 296[5]

Campo Santo

See also: Camposanto MonumentaleThe Campo Santo, also known as camposanto monumentale ("monumental cemetery") or camposanto vecchio ("old cemetery"), lies at the northern edge of the Square. It is a walled cemetery, which many claim is the most beautiful cemetery in the world. It is said to have been built around a shipload of sacred soil from Golgotha, brought back to Pisa from the Fourth Crusade by Ubaldo de' Lanfranchi, archbishop of Pisa in the 12th century, hence the name "Campo Santo" (Holy Field).

The building itself dates from a century later and was erected over the earlier burial ground. The building of this huge, oblong Gothic cloister began in 1278 by the architect Giovanni di Simone. He died in 1284 when Pisa suffered a defeat in a naval battle of Meloria against the Genoans. The cemetery was only completed in 1464. The outer wall is composed of 43 blind arches. There are two doorways. The one on the right is crowned by a gracious Gothic tabernacle. It contains the Virgin Mary with Child, surrounded by four saints. It is the work from the second half of the 14th century by a follower of Giovanni Pisano. Most of the tombs are under the arcades, although a few are on the central lawn. The inner court is surrounded by elaborate round arches with slender mullions and plurilobed tracery.

It contained a huge collection of Roman sculptures and sarcophagi, but now there are only 84 left. The walls were once covered in frescoes, the first were applied in 1360, the last about three centuries later. The Stories of the Old Testament by Benozzo Gozzoli (15th century) were situated in the north gallery, while the south arcade was famous for the Stories of the Genesis by Piero di Puccio (end 15th century). The most remarkable fresco is the realistic The Triumph of Death, the work of Buonamico Buffalmacco. But on 27 July 1944 incendiary bombs dropped by Allied aircraft set the roof on fire and covered them in molten lead, all but destroying them. Since 1945 restoration works have been going on and now the Campo Santo has been brought back to its original state.

The Spedale Nuovo di Santo Spirito

On the southest edge of the square there is the building of Spedale Nuovo di Santo Spirito ("New Hospital of Holy Spirit") built in 1257 by Giovanni di Simone maybe over a preexisting hospital. The function of this hospital was to help pilgrims, poor, sick people and abandoned children with a shelter. It later changed its name in Spedale della Misericordia ("Hospital of the Mercy") or di Santa Chiara ("Sant Claire") that was the name of the little church included in the complex.

The exterior was in brick walls with two-light windows in gothic style, whereas the interior was painted in two colors, black and white, to imitate the marble colors of the other buildings. During the Medici domination of the city, in 1562, the hospital was restructured according to Florentine renaissance canons: all the doors and windows were modified with new rectangular ones encased in gray sandstone.

Nowadays the building is no more an hospital. In the middle part of it, since 1979 is host the Museum of Sinopias where are kept the original drawings of the Camposanto frescoes.

See also

- Cathedral architecture

- Cathedrals in Italy

References

- ^ Carlo Collodi (1883). "Campo de' Miracoli 'in Italian". http://www.linguaggioglobale.com/Pinocchio/txt/18.htm. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ^ Barsali, G.; U. Castelli, R. Gagetti, O. Parra (1995). Pisa, History and Masterpieces. Florence: Bonechi Edizioni "Il Turismo" S.r.l.. pp. 46. ISBN 88-7204-192-9.

- ^ Michael Greenhalgh (1978). "Classicism from the Fall of Rome to Nicola Pisano: Survival and Revival". http://rubens.anu.edu.au/new/books_and_papers/classical_tradition_book/chap1.html. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- ^ "Leaning Tower of Pisa: 1920's Photo of Dal Pozzo". www.endex.com. http://www.endex.com/gf/buildings/ltpisa/ltpinfo/BellsFile/DalPozzo.htm. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ Davies, Andrew (2005). The Children's Visual World Atlas. Sydney, Australia: The Fog Press. ISBN 1-740893-17-4.

Sources

- Tobino, Mario (1982). Pisa la Piazza dei Miracoli. De Agostini.

External links

- Official website

- Photo gallery

- Field of Miracles

- Interactive High resolution 360° Panoramic Photo of Piazza dei Miracoli Virtual Tour by Hans von Weissenfluh

- Piazza dei Miracoli digital media archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from a University of Ferrara/CyArk research partnership.

Coordinates: 43°43′24″N 10°23′43″E / 43.72333°N 10.39528°E

Categories:- Piazzas in Pisa

- Buildings and structures in Pisa

- Romanesque architecture in Tuscany

- World Heritage Sites in Italy

- Domes

- Sites of papal elections

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.