- The Day After

-

This article is about the 1983 television film. For other uses, see The Day After (disambiguation).

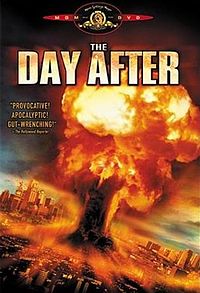

The Day After

The Day After DVD coverGenre Science fiction

PostapocalypticDirected by Nicholas Meyer Produced by Robert Papazian Written by Edward Hume Starring Jason Robards

JoBeth Williams

Steve Guttenberg

John Cullum

John Lithgow

Amy MadiganMusic by David Raksin

Virgil ThomsonCountry United States Language English Original channel ABC Release date November 20, 1983 Running time 126 minutes The Day After is a 1983 American television movie which aired on November 20, 1983, on the ABC television network. It was seen by more than 100 million people during its initial broadcast.[1]

The film portrays a fictional war between NATO forces and the Warsaw Pact that rapidly escalates into a full scale nuclear exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union. It focuses on the residents of Lawrence, Kansas, and Kansas City, Missouri, as well as several family farms situated next to nuclear missile silos.

The cast includes JoBeth Williams, Steve Guttenberg, John Cullum, Jason Robards and John Lithgow. The film was written by Edward Hume, produced by Robert Papazian and directed by Nicholas Meyer. It was released on DVD on May 18, 2004, with MGM.

Contents

Storyline

Background on the war

The chronology of the events leading up to the war is depicted entirely via television and radio news broadcasts. The Soviet Union is shown to have commenced a military buildup in East Germany with the goal of intimidating the United States into withdrawing from West Berlin. When the United States does not back down, Soviet armored divisions are sent to the border between West and East Germany.

During the late hours of Friday, September 15, news broadcasts report a "widespread rebellion among several divisions of the East German Army." As a result, the Soviets blockade West Berlin. Tensions mount and the United States issues an ultimatum that the Soviets stand down from the blockade by 6:00 A.M. the next day, or it will be interpreted as an act of war. The Soviets refuse, and the President of the United States puts all U.S. military forces around the world on a "stage 2 alert."

On Saturday, September 16, NATO forces in West Germany invade East Germany through the Helmstedt checkpoint to free Berlin. The Soviets hold the Marienborn corridor and inflict heavy casualties on NATO troops. Two Soviet MiG-25s cross into West German airspace and bomb a NATO munitions storage facility, also striking a school and a hospital. A subsequent radio broadcast states that Moscow is being evacuated. At this point, major U.S. cities begin mass evacuations as well. There soon follow unconfirmed reports that nuclear weapons were used in Wiesbaden and Frankfurt. Meanwhile, in the Persian Gulf, naval warfare erupts, as radio reports tell of ship sinkings on both sides.

Eventually the Soviet Army reaches the Rhine. Seeking to prevent Soviet forces from invading France and causing the rest of Western Europe to fall, NATO halts the Soviet advance by airbursting three low-yield nuclear weapons over advancing Soviet troops. Soviet forces counter by launching a nuclear strike on NATO headquarters in Brussels. In response, the United States Strategic Air Command begins scrambling B-52 bombers.

After the initial nuclear exchange in Europe, the United States enacts its "launch on warning" policy which will launch a full-scale nuclear attack on the Soviet Union if and when the United States receives indication that the Soviet Union is preparing to do the same.

The Soviet Air Force then destroys a BMEWS station in RAF Fylingdales, England and another at Beale Air Force Base in California. Meanwhile, on board the EC-135 Looking Glass aircraft, the order comes in from the President of the United States for a full nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. Almost simultaneously, an Air Force officer receives a report that a massive Soviet nuclear assault against the United States has been launched, stating "32 targets in track, with 10 impacting points." Another airman receives a report that over 300 Soviet ICBMs are inbound. It is deliberately unclear in the film whether the Soviet Union or the United States launches the main nuclear attack first.

The first salvo of the Soviet nuclear attack on the central United States (as shown from the point of view of the residents of Kansas and western Missouri) occurs at 3:38 PM Central Daylight Time when a large-yield nuclear weapon is air burst at a high altitude over Kansas City, Missouri, in order to generate an electromagnetic pulse and disable any defensive weapons covering the nearby Minuteman III missile silos of Whiteman AFB. Thirty seconds later, incoming Soviet ICBMs begin to hit military and population targets, including Kansas City. Sedalia, Missouri, all the way south to El Dorado Springs, Missouri, is blanketed with ground burst nuclear weapons. While there are no specifics given, it is strongly suggested in the film that America's cities, military, and industrial base are heavily damaged or destroyed. The aftermath depicts the central United States as a blackened wasteland of burned-out cities filled with radiation, burn, and blast victims. Eventually, the American President gives a radio address in which he declares that there is a ceasefire between the United States and the Soviet Union, which suffered similar damage.

Plot

The story follows several citizens and those they encounter after a nuclear attack on Kansas City, Missouri. The narrative structure of the film is presented as a before and after scenario with the first half introducing us to the various characters and their stories. The center section is the nuclear disaster itself. The latter half of the film shows the effects of the fallout on the characters.

Dr. Russell Oakes (Jason Robards) lives in the upper-class Brookside neighborhood with his wife (Georgann Johnson) and works in a hospital in downtown Kansas City. He is scheduled to teach a hematology class at the University of Kansas hospital in nearby Lawrence, Kansas, and is en route when he hears an alarming Emergency Broadcast System alert on his car radio. He pulls off the crowded motorway, attempts to contact his wife, but gives up due to the incredibly long line at a phone booth. Oakes heads back home down I-70, the only eastbound motorist. The nuclear attack begins and Kansas City is gripped with panic as air raid sirens wail. Oakes' car is disabled by the electromagnetic pulse, as is all electricity. Oakes is about thirty miles away from downtown when the missiles hit. His family, many colleagues and millions of others are killed. He walks ten miles to Lawrence and at the university hospital treats the wounded with Dr. Sam Hachiya (Calvin Jung) and Nurse Bauer (JoBeth Williams). Also at the university, science Professor Joe Huxley (John Lithgow) and students use a Geiger counter to monitor the level of nuclear fallout outside. They build a makeshift radio to maintain contact with Dr. Oakes at the hospital, as well as to locate any other broadcasting survivors outside the city.

Billy McCoy (William Allen Young) is an Airman First Class in the United States Air Force stationed at Whiteman AFB near Kansas City who is called into duty during the DEFCON 2 alert. He is among the first to witness the initial missile launches signaling the start of a full-scale nuclear war. After it becomes clear that a Soviet counterstrike is imminent, the unit panics; several Airmen stubbornly insist they stay on duty while the others, including McCoy, point out that it is futile. McCoy drives away in a truck to retrieve his wife and child in Sedalia, but it is disabled by the EMP blast. McCoy, realizing what has happened, flees the truck and finds an abandoned bunker, barely escaping the oncoming nuclear blast. After the attack, McCoy walks towards a town and finds an abandoned store, where he takes candy bars and other provisions while gunfire is heard in the distance. While standing in line for a drink of water from a well pump, McCoy befriends a man who is mute and shares his provisions. As they both begin to suffer the effects of radiation sickness, they leave a refugee camp and head to the hospital at Lawrence, where McCoy ultimately succumbs to the disease.

Farmer Jim Dahlberg (John Cullum) and his family live in rural Harrisonville, Missouri, far outside of Kansas City but very close to a field of missile silos. While the family is preparing for the wedding of their eldest daughter, Denise, they are forced to prepare for the impending attack by converting their basement into a makeshift fallout shelter. As the missiles are launched, Dahlberg forcefully carries his wife Eve, who denied the severity of the escalating crisis and continued the wedding preparations, down to the basement from their bedroom. Eve collapses into a fit of hysteria upon realizing a nuclear war has begun. While running to the shelter, the Dahlberg's son, Danny, stared directly at a nuclear explosion and was flash-blinded. University of Kansas student Stephen Klein (Steve Guttenberg), hitchhiking home to Joplin, Missouri, stumbles upon the farm and is taken in by the Dahlbergs. After several days in the basement, Denise, distraught over the situation and the unknown whereabouts of her fiance, Bruce, leaves the basement and runs outside. Klein goes after her and forces her back into the basement. In the weeks afterwards, Danny's condition deteriorates as does Denise's, who begins hemorrhaging while at a makeshift church service. Klein takes Danny and Denise to Lawrence for treatment. Dr. Hachiya attempts to treat Danny with no improvement, and Klein and Denise develop terminal radiation sickness. Dahlberg, upon returning from an emergency farmers meeting, confronts a group of survivors squatting on the farm and is shot to death.

Ultimately, the overall situation at the hospital becomes dire and grim. Dr. Oakes collapses from exhaustion and upon awakening finds out that Nurse Bauer has died from meningitis. Oakes, suffering from terminal radiation sickness, decides to return to Kansas City to "see my home one last time before I die" while Dr. Hachiya stays behind. Oakes hitches a ride on an Army National Guard truck, where he witnesses military personnel blindfolding and executing looters. At his home, he finds the charred remains of his wife's wristwatch and a family huddled in the ruins. Oakes angrily orders them to leave. The family silently offers Oakes food, causing him to collapse in despair.

As the scene fades to black, Professor Huxley forlornly calls into his makeshift radio: "Hello? This is Lawrence, Lawrence, Kansas. Is anybody there? Anybody? Anybody at all..."

Production

The Day After was the idea of ABC Motion Picture Division president Brandon Stoddard, who, after watching The China Syndrome, was so impressed that he envisioned creating a film exploring the effects of nuclear war on the United States. Stoddard asked his executive vice president of television movies and miniseries Stu Samuels to develop a script. Samuels created the title The Day After to emphasize that the story was not to be about a nuclear war itself but the aftermath. Samuels suggested several writers and eventually Stoddard commissioned veteran television writer Edward Hume to write the script in 1981. The American Broadcasting Company, which financed the production, was concerned about the graphic nature of the film and how to appropriately portray the subject on a family-oriented television channel. Hume undertook a massive amount of research on nuclear war and went through several drafts until finally ABC deemed the plot and characters acceptable.

Originally, the film was based more around and in Kansas City, Missouri. Kansas City was not bombed in the original script, although Whiteman Air Force Base was, making Kansas City suffer shock waves and the horde of survivors staggering into town. There was no Lawrence, Kansas in the story, although there was a small Kansas town called "Hampton". While Hume was writing the script, he and producer Robert Papazian, who had great experience in on-location shooting, took several trips to Kansas City to scout locations and met with officials from the Kansas film commission and from the Kansas tourist offices to search for a suitable location for "Hampton." It came down to a choice of either Warrensburg, Missouri and Lawrence, Kansas, both college towns — Warrensburg was home of Central Missouri State University and was near Whiteman Air Force Base and Lawrence was home of the University of Kansas and was near Kansas City. Hume and Papazian ended up selecting Lawrence, due to the access to a number of good locations: a university, a hospital, football and basketball venues, farms, beautiful countryside. Lawrence was also agreed upon as being the "geographic center" of the United States. The Lawrence people were urging ABC to change the name "Hampton" to "Lawrence" in the script.

Back in Los Angeles, the idea of making a TV movie showing the true effects of nuclear war on average American citizens was still stirring up controversy. ABC, Hume and Papazian realized that for the scene depicting the nuclear blast, they would have to use state-of-the-art special effects and they took the first step by hiring some of the best special effects people in the business to draw up some storyboards for the complicated blast scene. Then, ABC hired Robert Butler to direct the project. For several months, this group worked on drawing up storyboards and revising the script again and again; then, in the spring of 1982, Butler was forced to leave The Day After because of other contractual commitments. ABC then offered the project to two other directors, who both turned it down. Finally, in May, ABC hired feature film director Nicholas Meyer, who had just completed the blockbuster Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Meyer was apprehensive at first and doubted ABC would get away with making a television film on nuclear war without the censors diminishing its effect. However, after reading the script, Meyer agreed to direct The Day After.

However, Meyer wanted to make sure he would film the script he was offered. He didn't want the censors to chop up the film, nor did he want the film to be a regular Hollywood disaster movie from the start. Meyer figured the more The Day After resembled such a film, the less effective it would be. Meyer just wanted to dump the facts on nuclear war in people's laps. So first of all he made it clear to ABC that no TV or film stars should be in The Day After. ABC agreed, although they wanted to have one star to help attract European audiences to the film when it would be shown theatrically there. Later, while flying to visit his parents in New York City, Meyer happened to be on the same plane with Jason Robards and asked the star to join the cast.

Meyer plunged into several months of nuclear research, which made him quite pessimistic about the future. Every day, Meyer would come home feeling ill. He soon realized that what he was learning was making him sick. Meyer and Papazian also made trips to the ABC censors, and to the United States Department of Defense during this time. There were conflicts with both. Meyer had many heated arguments over elements in the script, both little and big, that the network censors wanted cut out of the film. The Department of Defense said they would cooperate with ABC if it was made clear in the script that the Soviet Union launched their missiles first, something Meyer and Papazian were at pains not to do.

In any case, Meyer, Papazian, Hume, and several casting directors spent most of July, 1982 taking numerous trips to Kansas City. In between casting in Los Angeles, where they stuck mostly to unknowns, they would fly to the Kansas City area to interview local actors and scenery. They were hoping to find some real Midwesterners for smaller roles. Hollywood casting directors strolled through shopping malls in Kansas City, looking for local people to fill small and supporting roles, while the daily newspaper in Lawrence ran an advertisement calling for local residents of all ages to sign up for jobs as a large number of extras in the film and a professor of theater and film at the University of Kansas was hired to head up the local casting of the movie. Out of the eighty or so speaking parts, only fifteen were cast in Los Angeles. The remaining roles were filled in Kansas City and Lawrence.

While in Kansas City, Meyer and Papazian toured the Federal Emergency Management Agency offices in Kansas City. When asked what their plans for surviving nuclear war were, a FEMA official replied that they were experimenting with putting evacuation instructions in telephone books in New England. "In about six years, everyone should have them." This meeting led Meyer to later refer to FEMA as "a complete joke." It was during this time that the decision was made to change "Hampton" in the script to "Lawrence." Meyer and Hume figured since Lawrence was a real town, that it would be more believable and besides, Lawrence was a perfect choice to be a representative of Middle America. The town boasted a "socio-cultural mix," sat near the exact geographic center of the continental U.S., and Hume and Meyer's research told them that Lawrence was a prime missile target, because 150 Minuteman missile silos stood nearby. Lawrence had some great locations, and the people there were more supportive of the project. Suddenly, less emphasis was put on Kansas City, the decision was made to have the city completely annihilated in the script, and Lawrence was made the primary location in the film.

Filming

The Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Lawrence, Kansas, the town where much of "The Day After" takes place.

The Douglas County Courthouse in downtown Lawrence, Kansas, the town where much of "The Day After" takes place.

Production began on Monday, August 16, 1982, at a farm just west of Lawrence. Sunshine was needed but it turned out to be a dreadfully overcast day. The set required a floodlight. The crew set fire to the farm's red barn for one scene during the blast sequence (it was eventually cut). The owner of the farm was not paid, but ABC did compensate by building him a new barn. A set in rural Lawrence, depicting a schoolhouse, was made in six days from fiberglass "skins." On Monday, August 30, 1982, ABC shut down Rusty's IGA supermarket in Lawrence's Hillcrest Shopping Center from 7 A.M. until 2 P.M. to shoot a scene representing panic buying. A local man and his infant son came to the market, apparently unaware that ABC was filming a movie. The man reportedly saw the chaos and ran back into his car in fear.

Local extras were paid $75 to shave heads bald, have latex scar tissue and burn-marks pasted on their faces, be plastered with coats of artificial mud, and be dressed in tattered clothes for scenes of radiation sickness. They were requested not to bathe or shower until filming was completed. In a small Lawrence park, ABC set up a grimy shantytown to serve as home to survivors. It was known as "Tent City." On Friday, September 3, 1982, the cameras rolled with many students as extras. The next day, Jason Robards, the best-known "star" of the film, arrived and production moved to Lawrence Memorial Hospital.

Many local individuals and businesses profited. It was estimated in newspaper accounts that ABC spent $1 million in Lawrence, not all on the production. Meyer said he wanted the film not to take political stands, but rather just remind people of nuclear war's perils. He thought of the TV film as a gigantic public service announcement.

On September 6, in downtown Lawrence, the filmmakers repainted signs, changing the names of stores, staining the facades with soot. The large windows were shattered into sharp teeth, bricks were scattered and junked cars were painted with clouds of black spray. Two industrial-sized yellow fans bolted to a flatbed trailer blew clouds of white flakes into the air. This fallout-matter was actually cornflakes painted white.

Next day, students poured into Allen Fieldhouse, the basketball arena, the only place on campus big enough to accommodate so many wounded. A scene was filmed with thousands of radiation victims stretched out on the court floor.

On September 8, a four-mile stretch on K-10 between the Edgerton Road exit and the DeSoto interchange at former K-285 (now Lexington Avenue) was closed for shooting highway scenes representing a mass exodus on Interstate 70. On September 10, Robards' character was filmed returning to what is left of Kansas City to find his home.

ABC used the demolition site of the former St. Joseph Hospital located at Linwood Boulevard and Prospect Avenue in an inner-city neighborhood in Kansas City as the set. The network paid the city to halt demolition for a month so it could film scenes of destruction there. However, when the crew arrived, more demolition had apparently taken place. Meyer was angry, but then realized he could populate the area with fake corpses and junked cars "and then I got real happy." Robards was in makeup at 6 a.m. to look like a radiation poisoning victim. The makeup took three hours to apply. Passers-by strained for a closer look as Robards lifted the arm of a body stuck under fallen debris — just the arm, severed at the shoulder. It was at this site that the moving final scene where Dr. Oakes confronts a family of squatters was filmed.

The Liberty Memorial in downtown Kansas City, Missouri was an important but hard-to-reach location in "The Day After."

The Liberty Memorial in downtown Kansas City, Missouri was an important but hard-to-reach location in "The Day After."

There were more problems on September 11. Meyer had desperately wanted the Liberty Memorial, a tall war memorial in Penn Valley Park overlooking downtown Kansas City, for two scenes: postcard-perfect shots of Kansas City near the beginning and a scene of Robards stumbling through the ruins. However, one director of the local parks department was opposed to letting it be used for commercial purposes and expressed concern that ABC would damage the Memorial. A resolution was reached. By using fiberglass, the filmmakers made it look as if the Memorial had been reduced to rubble. Robards stumbled through debris once again. That evening, the cast and crew flew to Los Angeles.

Interior hospital scenes with Robards and JoBeth Williams were shot in L.A. Many scientific advisors from various fields were on set to ensure the accuracy of the explosion, its effects and its victims. The government, nervous of how it would be portrayed, didn't allow the production to use stock footage of nuclear explosions in the film, so ABC hired special effects creators. The result was a frighteningly real explosion and iconic "mushroom cloud" created by injecting oil-based paints and inks downward into a water tank with a piston, filmed at high speed with the camera mounted upside down. The image was then optically color- and contrast-inverted. The water tank used for the "mushroom clouds" was the same water tank used to create the "Mutara Nebula" special effect in The Wrath of Khan.

The Day After relied heavily on footage from other movies and from declassified government films. Extensive use of stock footage was interspersed with special effects of the mushroom clouds. While the majority of the missile launches came from United States Department of Defense footage of ICBM missile tests (mainly Minuteman IIIs from Vandenberg Air Force Base adjacent to Lompoc, California), all of the stock footage of missile launches were acquired from declassified DoD film libraries. The scenes of Air Force personnel aboard the Airborne Command Post receiving news of the incoming attack are footage of actual military personnel during a drill and had been aired several years earlier in a 1979 PBS documentary, "First Strike". In the original footage, the silo is "destroyed" by an incoming "attack" just moments before launching its missiles, which is why the final seconds of the launch countdown are not seen in this movie.

Further stock footage was taken from news events (fires and explosions) and the 1979 theatrical film Meteor (such as a bridge collapsing and the destruction of a tall office building originally used to depict the destruction of the World Trade Center in that film). Brief scenes of stampeding crowds were also borrowed from the disaster film Two-Minute Warning (1976). Other footage had been previously used in theatrical films such as Superman and Damnation Alley.

The editing of The Day After was one of the most nerve-wracking processes ABC had ever gone through in post-production of any of their films. There were many meetings with the censors and Nicholas Meyer was enraged and confused because the network actually cut out many scenes due to what it considered slow pacing, not because they were too controversial or too graphic.

The film was originally planned by the network as a four-hour "event" to be spread over two nights, having an actual total running time of 180 minutes without commercials. Meyer had felt the script was padded, and had suggested cutting out an hour worth of material and presenting the whole film during one night. The network had disagreed, and Meyer had filmed the entire script. Meanwhile, the network had found out it was difficult to find advertisers, considering the subject matter, and Meyer was told he could edit the film for a one-night version. Meyer's original cut ran two hours and twenty minutes, which he presented to the network. After the screening, the executives were sobbing and seemed deeply affected, making Meyer believe they approved of his cut. However, a long six-month struggle began over the final shape of the film. The network now wanted to trim the film to the bone, but Meyer and his editor Bill Dornisch refused to cooperate. Dornisch was fired, and Meyer walked off. Other editors were brought in to do their versions, but the network ultimately was not happy with their work. Meyer was finally brought back in, and a compromise was reached, with a final running time of 120 minutes.[2][3]

It was originally planned The Day After would be aired in May, but it was pushed back to November to allow for the post-production work that would reduce the film's length. The first major cut was made to the film that could be called "censorship": censors forced ABC to cut an entire scene of a child having a nightmare about nuclear holocaust and then sitting up, screaming. A psychiatrist told ABC that this would disturb children. "This strikes me as ludicrous", Meyer wrote in TV Guide at the time. "Not only in relation to the rest of the film, but also when contrasted with the huge doses of violence to be found on any average evening of TV viewing." In any case, a few more cuts were made, including to a scene where Denise is shown to possess a diaphragm and another scene where a hospital patient abruptly sits up screaming (this was excised from the original television broadcast, but then restored for home video releases). Meyer persuaded ABC to dedicate the film to the citizens of Lawrence and also to put a disclaimer at the end of the film, following the credits, letting the viewer know that The Day After downplayed the true effects of nuclear war so they would be able to have a story. The disclaimer also included a list of books the viewer can read to find out more on the subject. When the film was finished, Meyer vowed never to work in television again.

The Day After received one of the largest promotional campaigns prior to its broadcast. Commercials aired several months in advance, ABC distributed half a million "viewer's guides", which discussed the dangers of nuclear war and prepared the viewer for the graphic scenes of mushroom clouds and radiation burn victims. Discussion groups were also formed nationwide. Some schools required their students to watch it as a homework assignment and discuss it the next morning in class, while others encouraged parents not to allow their children to view the film at all.[citation needed]

Music

Composer David Raksin wrote original music and adapted music from The River (a documentary film score by concert composer Virgil Thomson). Although he recorded just under 30 minutes of music, much of it was edited out of the final cut.

Deleted and alternate scenes

Due to the film being shortened from the original four hours to 2½, several planned special-effects scenes were scrapped, although storyboards were made in anticipation of a possible "expanded" version. They included a "bird's eye" view of Kansas City at the moment of two nuclear detonations as seen from a 737 on approach, as well as simulated newsreel footage of the tactical nuclear exchanges in Germany between NATO and Warsaw Pact troops.

ABC censors severely toned down scenes to reduce the body count or severe burn victims. Meyer refused to remove key scenes (such as the "lady in the bathtub" near the film's end), but reportedly some 8½ minutes of excised footage still exist, significantly more graphic. Some footage was reinstated for the film's release on home video.

JoBeth Williams' character was originally scripted with a death scene, asking whether the living envy the dead in a nuclear war's aftermath. This scene was cut when the film was reduced to 2½ hours. In the released version, Nurse Bauer's death occurs off-camera and is mentioned by Dr. Hachiya as having been due to meningitis. The dialogue was garbled and some viewers failed to hear the cause of death on the first viewing.

One cut scene shows a battle between surviving students over food. The two sides were to be athletes versus the science students under the guidance of Professor Huxley. Another brief scene later cut related to a firing squad, where two U. S. soldiers are blindfolded and executed. An officer reads the charges, verdict and sentence, as a bandaged chaplain reads the Last Rites. A similar sequence occurs in a 1965 UK-produced faux documentary, The War Game.

In the original broadcast, when the President addressed the nation, the voice was an imitation of Ronald Reagan. In subsequent broadcasts, that voice was overdubbed by a stock actor.

Reaction

On its original broadcast (Sunday, November 20, 1983), ABC and local TV affiliates opened 1-800 hotlines with counselors standing by. There were no commercial breaks after the nuclear attack. ABC then aired a live debate, hosted by Nightline's Ted Koppel, featuring scientist Carl Sagan, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Elie Wiesel, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, General Brent Scowcroft and conservative writer William F. Buckley, Jr.. Sagan argued against nuclear proliferation, while Buckley promoted the concept of nuclear deterrence. Sagan described the arms race in the following terms: "Imagine a room awash in gasoline, and there are two implacable enemies in that room. One of them has nine thousand matches, the other seven thousand matches. Each of them is concerned about who's ahead, who's stronger."

One psychotherapist counseled viewers at Shawnee Mission East High School in the Kansas City suburbs and 1,000 others held candles at a peace vigil in Penn Valley Park. A discussion group called Let Lawrence Live was formed by the English department at the university and dozens from the Humanities department gathered on the Kansas campus in front of the Memorial Campanile and lit candles in a peace vigil. At Baker University, a private school in Baldwin City, Kansas, roughly 10 miles south of Lawrence, a number of students drove around the city, looking at sites depicted in the film as having been destroyed.

The film provoked much political debate. Some argued that the film underscored the true personal horror of nuclear conflict[citation needed] and that the United States should therefore renounce the "first use" of nuclear weapons, a policy which had been a cornerstone of NATO defense planning in Europe.

Critics tended to claim the film was either sensationalizing nuclear war or that it was too tame.[4] The special effects and realistic portrayal of nuclear war received praise. The film received twelve Emmy nominations and won two Emmy awards.

Nearly 100 million Americans watched The Day After on its first broadcast, a record audience for a made-for-TV movie. Producers Sales Organization picked up international distribution rights to the film for the sum of $1,500 and released the film theatrically around the world to great success[citation needed] in the Eastern Bloc, China, North Korea and Cuba (this international version contained six minutes of footage not in the telecast edition). Since commercials are not sold in these markets, Producers Sales Organization lost an undisclosed sum of money. Years later this international version was released to tape by Embassy Home Entertainment (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer now holds the video rights in the US).

Commentator Ben Stein, critical of the movie's message (i.e. that the strategy of Mutual Assured Destruction would lead to a war), wrote in the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner what life might be like in an America under Soviet occupation. (Stein's idea was eventually dramatized in the miniseries Amerika, also broadcast by ABC.)

The New York Post accused Meyer of being a traitor, writing, "Why is Nicholas Meyers doing Yuri Andropov's work for him?"[5] Phyllis Schlafly declared that "This film was made by people who want to disarm the country, and who are willing to make a $7 million contribution to that cause".[5] Much press comment focused on the unanswered question in the film of who started the war.[5]

Effects on policymakers

President Ronald Reagan watched the film several days before its screening, on 5 November 1983.[5] He wrote in his diary that the film was "very effective and left me greatly depressed,"[5] and that it changed his mind on the prevailing policy on a "nuclear war".[6] The film was also screened for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. A government advisor who attended the screening, a friend of Meyer's, told him "If you wanted to draw blood, you did it. Those guys sat there like they were turned to stone."[5] Three years later, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty was signed at Reykjavik, and in Reagan's memoirs he drew a direct line from the film to the signing.[5] An oft-repeated story[by whom?] was that Reagan sent Meyer a telegram after the summit, saying, "Don't think your movie didn't have any part of this, because it did."[2] In a 2010 interview, Meyer said that this was a myth, and that the sentiment stemmed from a friend's letter to Meyer; he suggested the story had origins in editing notes received from the White House during the production, which "may have been a joke, but it wouldn't surprise me, him being an old Hollywood guy".[5]

The film also had impact outside the US. In 1987, during the era of Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost and perestroika reforms, the film was shown on Soviet television.

Cast

Striving for a documentary style[citation needed], casting director Hank McCann used many newcomers or obscure actors. Jason Robards and John Cullum were the best-known actors in the production. Bibi Besch was a relative unknown, recently thrust into the spotlight as Dr. Carol Marcus in Meyer's Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Steve Guttenberg, who went on to considerable success, was at the time known for the 1982 Barry Levinson comedy Diner. Stephen Furst was known primarily as Flounder in National Lampoon's Animal House. George Petrie, a stock player on several incarnations of Jackie Gleason's television series and the Ewing family lawyer in Dallas, had a small role as a doctor. Cullum and Besch later played Holling Vincoeur and Maggie O'Connell's mother on Northern Exposure.

Locals filled smaller supporting roles. Jeff East, who played Bruce Gallatin, was a local Kansas City actor who had appeared in Superman as the young Clark Kent. Doug Scott and Ellen Anthony, who played the younger Dahlberg children, were found in Lawrence (Anthony was the daughter of the film's Kansas casting director Jack Wright). Arliss Howard (who played an Airman) went on to major films, but at the time was a local thespian. Charles Oldfather, Herk Harvey and Charles Whitman, all at one time professors at The University of Kansas, were cast as farmers.

John Lithgow, JoBeth Williams and Amy Madigan were relative newcomers. Williams had recently starred in Poltergeist and Lithgow in The World According to Garp, earning an Academy Award nomination. He soon appeared 1983's eventual Best Picture Terms of Endearment and was nominated again. Madigan would star in films such as Field of Dreams.

- The Oakes

- Jason Robards as Dr. Russell Oakes

- Georgann Johnson as Helen Oakes

- Kyle Aletter as Marilyn Oakes

- The Dahlbergs

- John Cullum as Jim Dahlberg

- Bibi Besch as Eve Dahlberg

- Lori Lethin as Denise Dahlberg

- Doug Scott as Danny Dahlberg

- Ellen Anthony as Joleen Dahlberg

- Hospital staff

- JoBeth Williams as Nurse Nancy Bauer

- Calvin Jung as Dr. Sam Hachiya

- Lin McCarthy as Dr. Austin

- Rosanna Huffman as Dr. Wallenberg

- George Petrie as Dr. Landowska

- Jonathan Estrin as Julian French

- Others

- Steve Guttenberg as Stephen Klein

- John Lithgow as Joe Huxley

- Amy Madigan as Alison Ransom

- William Allen Young as Airman First Class Billy McCoy

- Jeff East as Bruce Gallatin

- Dennis Lipscomb as Reverend Walker

- Clayton Day as Dennis Hendry

- Antonie Becker as Ellen Hendry

- Stephen Furst as Aldo

- Arliss Howard as Tom Cooper

- Stan Wilson as Vinnie Conrad

- Harry Bugin as Man at phone

Awards

Emmy Awards won:

- Outstanding Film Sound Editing for a Limited Series or a Special

- Outstanding Achievement In Special Visual Effects

Emmy Award nominations:

- Outstanding Achievement in Hairstyling

- Outstanding Achievement in Makeup

- Outstanding Art Direction for a Limited Series or a Special

- Outstanding Cinematography for a Limited Series or a Special (Gayne Rescher)

- Outstanding Directing in a Limited Series or a Special (Nicholas Meyer)

- Outstanding Drama/Comedy Special (Robert Papazian)

- Outstanding Film Editing for a Limited Series or a Special (William Dornisch and Robert Florio)

- Outstanding Film Sound Mixing for a Limited Series or a Special

- Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Limited Series or a Special (John Lithgow)

- Outstanding Writing in a Limited Series or a Special (Edward Hume)

See also

- Kansas City Plant

- Able Archer 83

- Doomsday device

- Nuclear weapons in popular culture

- List of nuclear holocaust fiction

- Barefoot Gen Fact-based manga which subsequently was adapted into film, anime and television drama formats.

- The War Game 1965 BBC television drama documentary.

- Testament (film) 1983 made for television movie.

- Warday 1984 novel.

- Threads 1984 BBC television drama.

- Amerika 1987 ABC television miniseries.

References

- ^ "Tipoff". The Ledger. 20 January 1989. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=8rROAAAAIBAJ&sjid=BvwDAAAAIBAJ&pg=1194,1429539&dq=jobeth+williams+tv+movie+nielsen+ratings&hl=en. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ a b Niccum, John. "Fallout from The Day After". lawrence.com. http://www.lawrence.com/news/2003/nov/19/fallout_from/. Retrieved 11 October 2011.

- ^ Meyer, Nicholas, "The View From the Bridge: Memories of Star Trek and a Life in Hollywood", page 150. Viking Adult, 2009

- ^ Susan Emmanuel. "The Day After". The Museum of Broadcast Communications. http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/D/htmlD/dayafterth/dayafter.htm.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Empire, "How Ronald Reagan Learned To Start Worrying And Stop Loving The Bomb", November 2010, pp134-140

- ^ Reagan, An American Life, 585

External links

- The Day After at the Internet Movie Database

- The Day After at AllRovi

- Footage from the attack scenes

Films directed by Nicholas Meyer 1970s Time After Time (1979)1980s Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) · The Day After (1983) · Volunteers (1985) · The Deceivers (1988)1990s Categories:- English-language films

- 1983 television films

- American films

- American television films

- American disaster films

- Cold War films

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films directed by Nicholas Meyer

- Films set in Kansas

- Films set in Missouri

- Science fiction television films

- Science fiction war films

- World War III speculative fiction

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.