- Mogao Caves

-

Mogao Caves * UNESCO World Heritage Site

Country China Type Cultural Criteria i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi Reference 440 Region ** Asia-Pacific Inscription history Inscription 1987 (11th Session) * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List

** Region as classified by UNESCOThe Mogao Caves or Mogao Grottoes (Chinese: 莫高窟; pinyin: Mògāo kū), also known as the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas (Chinese: 千佛洞; pinyin: qiān fó dòng), form a system of 492 temples 25 km (16 mi) southeast of the center of Dunhuang, an oasis strategically located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu province, China. The caves may also be known as the Dunhuang Caves, however, this term may also include other Buddhist cave sites in the Dunhuang area, such as the Western Thousand Buddha Caves, and the Yulin Caves farther away. The caves contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist art spanning a period of 1,000 years.[1] The first caves were dug out 366 AD as places of Buddhist meditation and worship.[2] The Mogao Caves are the best known of the Chinese Buddhist grottoes and, along with Longmen Grottoes and Yungang Grottoes, are one of the three famous ancient Buddhist sculptural sites of China.

Contents

History

Dunhuang was established as a frontier garrison outpost by the Han Dynasty Emperor Wudi to protect against the Xiongnu in 111 BC. It also became an important gateway to the West, a centre of commerce along the Silk Road, as well as a meeting place of various people and religions such as Buddhism.

The construction of the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang is generally taken to have began some time in the fourth century AD. According to a book written during the reign of Tang Empress Wu, Fokan Ji (佛龕記, An Account of Buddhist Shrines) by Li Junxiu (李君修), a Buddhist monk named Lè Zūn (樂尊, which may also be pronounced Yuezun) had a vision of a thousand Buddhas bathed in golden light at the site in 366 AD, inspiring him to built a cave here.[3] The story is also found in other sources, such as in inscriptions on a stele in cave 332, an earlier date of 353 AD however was given in another document (沙州土鏡).[4] He was later joined by a second monk Faliang (法良), and the site gradually grew, by Northern Liang a small community of monks had formed at the site. Members of the ruling family of Northern Wei and Northern Zhou constructed many caves here, and it flourished in the short-lived Sui Dynasty whose emperors promoted Buddhism. By the Tang Dynasty, the number of caves had reached over a thousand.[5]

The caves initially served only as a place of meditation, but developed to serve the monasteries that sprung up nearby in the early periods, and by the Sui and Tang dynasty, Mogao had become a place of worship and pilgrimage for the public.[6] From the 4th until the 14th century, caves were constructed by monks to serve as shrines with funds from donors. These caves were elaborately painted, the cave paintings and architecture served as aids to meditation, as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as mnemonic devices, and as teaching tools to inform those illiterate about Buddhist beliefs and stories. The major caves were sponsored by patrons such as wealthy merchants, local ruling elite, foreign dignitaries, as well as Chinese emperors.

During the Tang Dynasty, Dunhuang had became the main hub of commerce of the Silk Road and a major religious centre. A large number of the caves were constructed at Mogao during this era, including the two large statues of Buddha at the site, the largest one constructed following an edict by Tang Empress Wu Zetian. The site escaped the persecution of Buddhists ordered by Emperor Wuzong in 845 as it was then under Tibetan control. As a frontier town, Dunhuang had been occupied at various times by other non-Han Chinese people. After the Tang Dynasty, the site went into a gradual decline, and construction of new caves ceased entirely after the Yuan Dynasty. Islam had conquered much of Central Asia, and the Silk Road declined in importance when trading via sea-routes began to dominate Chinese trade with the outside world. During the Ming Dynasty, the Silk Road was finally officially abandoned, and Dunhuang slowly became depopulated and largely forgotten by the outside world. Most of the Mogao caves were abandoned, the site however was still a place of pilgrimage and used as a place of worship by local people at the beginning of the twentieth century when there was renewed interest in the site.

Discovery and revival

During late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, Western explorers began to show interest in the ancient Silk Road and the lost cities of Central Asia, and those who passed through Dunhuang noted the murals and artefacts such as the Stele of Sulaiman at Mogao. The biggest discovery however came from a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu (王圓籙) who appointed himself guardian of some of these temples around the turn of the century.

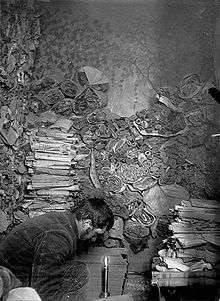

Some of the caves had by then been blocked by sand, and Wang set about clearing away the sand and made an attempt at repairing the site. In one such cave, in the year 1900, Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave.[7] Behind the wall was a small cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts. In the next few years, Wang took some manuscripts to show to various officials who expressed varying level of interest, but in 1904 Wang re-sealed the cave following an order by the governor of Gansu.

Words of Wang's discovery drew the attention of a joint British/Indian group led by Hungarian archaeologist Aurel Stein who was on an archaeological expedition in the area n 1907.[8] Stein negotiated with Wang to allow him to remove a significant number of manuscripts as well as the finest paintings and textiles for a fee. He was followed by a French expedition under Paul Pelliot who acquired many thousand of items in 1908, then a Japanese expedition under Otani Kozui in 1911, and a Russian expedition under Sergei F. Oldenburg in 1914. A well-known scholar Luo Zhenyu (羅振玉) edited some of the manuscripts Pelliot acquired into a volume which was then published in 1909 as "Manuscripts of the Dunhuang Caves" (敦煌石室遺書).[9]

Stein and Pelliot provoked much interest in the West about the Dunhuang Caves, however, there were initially little interest in official circles in China. Concerned that the remaining manuscripts might be lost, Luo Zhenyu and others persuaded the Ministry of Education to recover the rest of the manuscripts to be sent to Peking (Beijing) in 1910. However, not all the remaining manuscripts were taken to Peking, and of those retrieved, many were then stolen. Some of the caves were damaged when the caves were used by the local authority in 1921 to house Russian soldiers fleeing the civil war following the Russian Revolution. In 1924, American explorer Langdon Warner removed a number of murals as well as a statue from some of the caves.

The travel of Zhang Qian to the West, mural from cave 323, 618-712 AD. Detail view.

The travel of Zhang Qian to the West, mural from cave 323, 618-712 AD. Detail view.

The situation improved in 1941, when the painter Zhang Daqian (張大千) arrived at the caves with a small team of assistants and stayed for two and a half years to repair and copy the murals. He then exhibited and published the copies of the murals, which helped to publicize and give much prominence to the art of Dunhuang within China.[10] Historian Xiang Da then persuaded Yu Youren, a prominent member of the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party), to set up an institution, Research Institute of Dunhuang Art (later renamed Dunhuang Academy), at Mogao in 1944 to look after the site and its contents. In 1956, the first Premier of the People's Republic of China, Zhou Enlai, took a personal interest in the caves and sanctioned a grant to repair and protect the site; and in 1961, the Mogao Caves were declared to be a specially protected historical monument by the State Council. The site escaped the widespread damage caused during the Cultural Revolution.[11]

Today, the site is the subject of an ongoing archaeological project.[12] The Mogao Caves became one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1987.[1] From 1988 to 1995 a further 248 caves were discovered to the North of the 487 caves known since the early 1900s.[13]

The Library Cave

The cave no. 17 discovered by Wang Yuanlu came to be known as the Library Cave. It is sited off the entrance leading to cave no.16, and was originally used as a memorial cave for a local monk Hongbian on his death in 862 AD. Hongbian, from a wealthy Wu family, was responsible for the construction of cave 16, and the Library Cave may have been used as his retreat in his life time. The cave originally contained his statue which was move to another cave when it was used to keep manuscripts, some of which bear Hongbian's seal. Large number of documents dating from 406 to 1002 AD were found in the cave, heaped up in closely packed layers of bundles of scrolls. The Library Cave also contained textiles such as banners, numerous damaged figurines of Buddhas, and other Buddhist paraphernalia. According to Stein who was the first to describe the cave in its original state:[14]

“ Heaped up in layers, but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest's little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet, and filling, as subsequent measurement showed, close on 500 cubic feet. The area left clear within the room was just sufficient for two people to stand in. ” — Aurel Stein, Ruins of Desert Cathay: Vol. IIThe Library Cave was walled off sometime early in the 11th century. A number of theories have been proposed as the reason for sealing the caves. Stein first proposed that the cave had become a waste repository for venerable, damaged and used manuscripts and hallowed paraphernalia and then sealed perhaps when the place came under threat. Following this interpretation some suggested that the handwritten manuscripts of the Tripitaka became obsolete when printing became widespread, the older manuscripts were therefore stored away.[15] Another suggestion is that the cave was simply used as a book storehouse for documents which accumulated over a century and a half, then sealed up when it became full.[16]

Others, such as Pelliot, suggested an alternative scenario, that the monks hurriedly hid the documents in advance of an attack by invaders, perhaps when Xi Xia invaded in 1035. This theory was proposed in light of the absence of document from Xi Xia and the disordered state Pelliot found the room in (perhaps a misinterpretation because the room was disturbed by Stein the year before). Another theory posits that the items were from a monastic library and hidden due to threats from Muslims who were moving eastward. This theory proposes that that the monks of a nearby monastery heard about the fall of the Buddhist kingdom of Khotan to Karakhanids invaders from Kashgar in 1006 and the destruction it caused, so they sealed their library to avoid them being destroyed.[17] The latest date recorded in the documents found in the cave is generally accepted to be 1002, and although other dates have been suggested, the cave was likely to have been sealed not long after that date.

The Dunhuang manuscripts

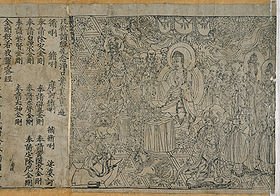

Main article: Dunhuang manuscripts The Chinese Diamond Sūtra, the oldest known dated printed book in the world, British Library Or.8210/P.2.

The Chinese Diamond Sūtra, the oldest known dated printed book in the world, British Library Or.8210/P.2.

The manuscripts from the the Library Cave date from fifth century until early eleventh century when it was sealed. Up to 50,000 manuscripts may have been kept there, one of the greatest treasure trove of ancient documents found. While most of them are in Chinese, large number of documents are in various other languages such as Tibetan, Uigur, Sanskrit, and Sogdian, including the then little known Khotanese. They may be old hemp paper scrolls in Chinese and many other languages, Tibetan pothis, and paintings on hemp, silk or paper. The subject matter of the great majority of the scrolls is Buddhist in nature, but it also covers a diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works are original commentaries, apocryphal works, workbooks, books of prayers, Confucian works, Taoist works, Nestorian Christian works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises.

Many of the manuscripts were previously unknown or thought lost, and the manuscripts provide a unique insight into religious and secular matters of Northern China as well as other Central Asian kingdoms from the early periods, through to Tang and early Song Dynasty. The manuscripts found in the Library Cave include the earliest dated printed book, the Diamond Sutra from 868 AD which was first translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the fourth century. These scrolls also include manuscripts that ranged from the Nestorian Jesus Sutras to Dunhuang Go Manual and ancient music scores, as well as the image of the Chinese astronomy Dunhuang map. These scrolls chronicle the development of Buddhism in China, record the political and cultural life of the time, as well as providing documents of mundane secular matters that give a rare glimpse into the lives of ordinary people of these eras.

The manuscripts were dispersed all over the world in the aftermath of the discovery. Stein's acquisition was split between Britain and India because his expedition was funded by both countries. Stein had the first pick and he was able to collect around 7,000 complete manuscripts and 6,000 fragments, although these include many duplicate copies of the Diamond and Lotus Sutras. Pelliot took almost 10,000 documents, but unlike Stein, Pelliot was a trained sinologist fluent in Chinese and was therefore able to pick a better selection of documents than Stein. Pelliot was interested in the more unusual and exotic of the Dunhuang manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated lay men's groups. Many of these manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest in which the Buddhist texts were written on the opposite side of the paper. Hundreds more of the manuscripts were sold by Wang to Otani Kozui and Sergei Oldenburg. Efforts are now underway to reconstitute digitally the Library Cave manuscripts and these are now available as part of International Dunhuang Project.

Art

Mural of Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin), Worshipping Bodhisattvas and Mendicant in cave 57. Early Tang.

Mural of Avalokiteśvara (Guanyin), Worshipping Bodhisattvas and Mendicant in cave 57. Early Tang.

The art of Dunhuang covers more than ten major genres, such as architecture, stucco sculpture, wall paintings, silk paintings, calligraphy, woodblock printing, embroidery, literature, music and dance, and popular entertainment.[18]

Early art of Dunhuang showed strong influence from India and Central Asia, many of the caves for example followed the Indian central column style of cave construction. The art however became gradually sinicized.

The murals on the caves covered a long period of history, from the 5th to the 14th century. The murals are extensive, covering an area of 450,000 square feet (42,000 m²). They are valued for the the scale and richness of content as well as their artistry. The murals are largely of Buddhist theme, some however are of traditional mythical themes and portraits of patrons. These murals documents the changing styles of Buddhist art for nearly a thousand years. The artistry of the murals reached its apogee during the Tang period. The quality of the art work dropped after the tenth century.

Caves

The caves were cut into the side of a cliff which is close to two kilometers long. At its height during the Tang Dynasty, there were more than a thousands caves, but over time, many of the caves were lost, including the earliest caves. 735 caves currently exist in Mogao, the best-known ones are the 487 caves located in the southern section of the cliff which are places of pilgrimage and worship. 248 caves have also been found to the north which were living quarters, meditation and burial sites for the monks. The caves at the southern section are decorated, while those at the north section are mostly plain.

From the murals, sculptures and other objects found in the caves, around five hundred caves were determined to be built in the following era (list from the 1980s, more have been identified since):

- Sixteen Kingdoms (366-439) - 7 caves, the oldest dated to Northern Liang period.

- Northern Wei (439-534) and Western Wei (535-556) - 10 from each phase

- Northern Zhou (557-580) - 15 caves

- Sui Dynasty (581-618) - 70 caves

- Early Tang (618- 704) - 44 caves

- High Tang (705-780) - 80 caves

- Middle Tang (781-847) - 44 caves (This era in Dunhuang is also known as the Tibetan period because Dunhuang was then under Tibetan occupation.)

- Late Tang (848-906) - 60 caves

- The Five Dynasty (907-923) - 32 caves

- Song Dynasty (960-1035)- 43 caves

- Western Xia (1036-1226) - 82 caves

- Yuan Dynasty (1227-1368) - 10 caves

Gallery

-

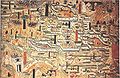

10th century mural from Cave 61, showing Tang Buddhist monasteries of Mount Wutai, Shanxi province

-

The travel of Zhang Qian to the West, complete view, c. 700 AD

-

The travel of Zhang Qian to the West, close-up view of Emperor Han Wudi (156 – 87 BC) worshipping two statues of the Buddha

-

A Tang Chinese silk landscape painting depicting a young Sakyamuni cutting his hair

See also

- List of World Heritage Sites in China

- Buddhism in China

- International Dunhuang Project

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Stele of Sulaiman

- Dunhuang Go Manual

- Silk Road

- Three hares

- Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves

Footnotes

- ^ a b "Mogao Caves". UNESCO. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/440. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ Zhang Wengin

- ^ Fokan Ji 《佛龕記》 Original text: 莫高窟者厥,秦建元二年,有沙门乐僔,戒行清忠,执心恬静。当杖锡林野,行至此山,忽见金光,状有千佛。□□□□□,造窟一龛。

- ^ Le Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=9jb364g4BvoC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ "Dunhuang -- Mogao Caves --". http://www.travelchinaguide.com/attraction/gansu/dunhuang/mogao_grottoes/index.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Xiuqing Yang (2007). Dunhuang Sees Great Changes Over the Years. China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 7508509161.

- ^ "Chinese Exploration and Excavations in Chinese Central Asia". International Dunhuang Project. http://idp.bl.uk/pages/collections_ch.a4d. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ Serindia vol. II pg. 801-802, Aurel Stein

- ^ Dunhuang shi shi yi shu

- ^ The Epochal Significance in Zhang Daqian's Copies of Dunhuang Fresco

- ^ Duan, Wenjie; Tan, Chung (1994). Dunhuang art: through the eyes of Duan Wenjie. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts. ISBN 81-7017-313-2. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=0SdXEVaFTJ0C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=daqin&f=false.

- ^ "The International Dunhuang Project". International Dunhuang Project. http://idp.bl.uk/. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ Brief report on the both the southern and northern caves

- ^ Opening of the hidden chapel M. Aurel Stein, Ruins of Desert Cathay: Vol II

- ^ Akira, Fujieda, "The Tun-Huan Manuscripts", in Essays on the sources for Chinese history (1973). edited by Donald D. Leslie, Colin Mackerras, and Wang Gungwu. Australian National University, ISBN 0-87249-329-6

- ^ The Provenance and Character of the Dunhuang Documents

- ^ The Nature of the Dunhuang Library Cave and the Reasons for its Sealing

- ^ Whitfield, Roderick, Susan Whitfield, and Neville Agnew. "Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road" (2000). The British Library. ISBN 0-7123-4697-x

References

- Duan Wenjie [editor-in-chief], Mural Paintings of the Dunhuang Mogao Grotto (1994) Kenbun-Sha, Inc. / China National Publications Import and Export Corporation, ISBN 4-906351-04-2

- Hopkirk, Peter. Foreign Devils on the Silk Road: The Search for the Lost Cities and Treasures of Chinese Central Asia (1980). Amherst: The University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0-87023-435-8

- Stein, M. Aurel. Ruins of Desert Cathay: Personal Narrative of Explorations in Central Asia and Westernmost China, volume 2 (1912). London: Macmillan.

- Whitfield, Roderick, Susan Whitfield, and Neville Agnew. "Cave Temples of Mogao: Art and History on the Silk Road" (2000). Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute. ISBN 0-89236-585-4

- Wood, Frances, "The Caves of the Thousand Buddhas: Buddhism on the Silk Road" in "The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia" (2002) by Frances Wood. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23786-2

- Zhang Wenbin, ed. "Dunhuang: A Centennial Commemoration of the Discovery of the Cave Library" (2000). Beijing: Morning Glory Publishers. ISBN 7-5054-0716-3

External links

- Introduction of the arts (mostly Buddhist arts) of the Mogao Caves with images

- A large collections of images of murals and other artifacts from the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang

- International Dunhuang Project

- Mogao caves video

Notable Caves of China East South Central Southwest Furong Cave • Shuang River Cave Group • Xueyu Cave • Zhijin Cave • Zhong CaveSoutheast Luobi Cave • Macaque CaveNorth Northeast Northwest World Heritage Sites in China East Classical Gardens of Suzhou · Fujian Tulou · Lushan National Park · Mount Huang (Huangshan) · Mount Sanqing (Sanqingshan) · Mount Tai (Taishan) · Mount Wuyi (Wuyishan) · Temple and Cemetery of Confucius and Kong Family Mansion, Qufu · Ancient villages in Southern Anhui - Xidi and Hongcun · West Lake Cultural Landscape of Hangzhou

South Central Ancient Building Complex in the Wudang Mountains · Historic Centre of Macau · Kaiping Diaolou and Villages · Longmen Grottoes · Historic Monuments of Dengfeng, including the Shaolin Monastery and Gaocheng Observatory · Wulingyuan Scenic and Historic Interest Area · Yin Xu

Southwest Dazu Rock Carvings · Historic Ensemble of the Potala Palace, including the Jokhang and Norbulingka · Huanglong Scenic and Historic Interest Area · Jiuzhaigou Valley Scenic and Historic Interest Area · Old Town of Lijiang · Mount Emei Scenic Area, including Leshan Giant Buddha Scenic Area · Mount Qingcheng and the Dujiangyan Irrigation System · Sichuan Giant Panda Sanctuaries · Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas

North Mount Wutai (Wutaishan) · Chengde Mountain Resort and its outlying temples including the Putuo Zongcheng Temple, Xumi Fushou Temple and the Puning Temple · Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang · Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian · Ancient City of Pingyao · Summer Palace, an Imperial Garden in Beijing · Temple of Heaven: an Imperial Sacrificial Altar in Beijing · Yungang Grottoes

Northeast Capital Cities and Tombs of the Ancient Koguryo Kingdom · Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang

Northwest Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor · Mogao Caves

Multiple regions Gansu topics General Geography Education Culture Tangwang languageCuisine Visitor attractions Jiayuguan Pass • Bingling Temple • Mogao Grottoes • Silk Route Museum • Labrang Monastery • Maijishan GrottoesCoordinates: 40°02′14″N 94°48′15″E / 40.03722°N 94.80417°E

Categories:- Former populated places in China

- Central Asian Buddhist sites

- Chinese Buddhist grottoes

- Sites along the Silk Road

- World Heritage Sites in China

- Chinese architectural history

- Dunhuang

- Gansu

- Buddhist pilgrimages

- Caves of Gansu

- Visitor attractions in Gansu

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.