- Roughtail stingray

-

Roughtail stingray

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Chondrichthyes Subclass: Elasmobranchii Order: Myliobatiformes Family: Dasyatidae Genus: Dasyatis Species: D. centroura Binomial name Dasyatis centroura

(Mitchill, 1815)

Range of the roughtail stingray Synonyms Dasybatus marinus Garman, 1913

Pastinaca acanthura Gronow, 1854

Pastinaca aspera Cuvier, 1816

Raia gesneri Cuvier, 1829

Raja centroura Mitchill, 1815

Trygon aldrovandi Risso, 1827

Trygon brucco Bonaparte, 1834

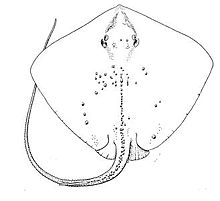

Trygon thalassia Müller & Henle, 1841The roughtail stingray (Dasyatis centroura) is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae, with separate populations in coastal waters of the northwestern, eastern, and southwestern Atlantic Ocean. This bottom-dwelling species typically inhabits sandy or muddy areas with patches of invertebrate cover, at a depth of 15–50 m (49–160 ft). It is seasonally migratory, overwintering in offshore waters and moving into coastal habitats for summer. The largest stingray in the Atlantic,[2] the roughtail stingray grows up to 2.6 m (8.5 ft) across and 300 kg (660 lb) in weight. It is plain in color, with an angular, diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc and a long, whip-tail tail bearing a subtle fin fold underneath. The many thorns on its back and tail serve to distinguish it from other stingrays that share its range.

Often found lying on the bottom buried in sediment, the roughtail stingray is a generalist predator that feeds on a variety of benthic invertebrates and bony fishes. It is aplacental viviparous, with the embryos receiving nourishment initially from yolk, and later from histotroph ("uterine milk") produced by the mother. In the northwestern Atlantic, females bear an annual litter of 4–6 young in fall and early winter, after a gestation period of 9–11 months. By contrast, in the Mediterranean there is evidence that females bear two litters of 2–6 young per year after a gestation period of only four months. Rays in the northwestern Atlantic are also larger at birth and sexual maturity than those from the Mediterranean. The venomous tail spine of the roughtail stingray is potentially dangerous to humans. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed this species under Least Concern overall and in the northwestern Atlantic, where it is not commercially utilized. However, in the Mediterranean and southwestern Atlantic it is subject to heavy fishing pressure and has been assessed as Near Threatened.

Contents

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The first description of the roughtail stingray was published by American naturalist Samuel Mitchell in one of the earliest North American works on ichthyology, a short treatise on the fishes of New York in the 1815 first volume of Transactions of the Literary and Philosophical Society of New York.[3][4] Mitchell based his account on specimens caught off Long Island, though did not designate any types, and named the new species Raja centroura, from the Greek centoro ("pricker") in reference to its thorns. Subsequent authors moved this species to the genus Dasyatis.[2][5] This ray may also be referred to as rough-tailed stingray, rough-tailed northern stingray, or thorny stingray.[6][7]

The taxonomy of the roughtail stingray is not fully resolved, with the disjunct northwestern Atlantic, southwestern Atlantic, and eastern Atlantic populations differing in life history and perhaps representing a complex of different species.[1] Lisa Rosenberger's 2001 phylogenetic analysis of 14 Dasyatis species, based on morphology, found that the roughtail stingray is the sister species to the broad stingray (D. lata), and that they form a clade with the southern stingray (D. americana) and the longtail stingray (D. longa).[8] The close relationship between the roughtail and southern stingrays was upheld by a genetic analysis published by Leticia de Almeida Leao Vaz and colleagues in 2006.[9] The roughtail and broad stingrays are found in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans respectively, and therefore likely diverged before or with the formation of the Isthmus of Panama (c. 3 Ma).[8]

Distribution and habitat

The roughtail stingray is broadly but discontinuously distributed in the coastal waters of the Atlantic Ocean. In the western Atlantic, it occurs from the Georges Bank off New England southward to Florida, the Bahamas, and the northeastern Gulf of Mexico; there are also scattered reports from Venezuela to Argentina. In the eastern Atlantic, it occurs from the southern Bay of Biscay to Angola, including the Mediterranean Sea, Madeira, and the Canary Islands. A single record from Quilon, India was likely a misidentification.[1]

One of the deepest-diving stingrays, the roughtail stingray has been recorded to a depth of 274 m (899 ft) in the Bahamas and regularly occurs down to 200 m (660 ft) in the Mediterranean.[7] However, it is most common at a depth of 15–50 m (49–160 ft).[6] This bottom-dwelling species favors live-bottom habitat (patches of rough terrain that are densely encrusted by sessile invertebrates), and also frequents adjacent open areas of sand or mud.[7] Rays in the northwestern Atlantic do not usually enter brackish water, whereas those off West Africa have been recorded from the lower reaches of large rivers.[10][11]

The favored temperature range of the roughtail stingray is 15–22 °C (59–72 °F), which is the most important factor determining its distribution. It conducts seasonal migrations off the eastern United States: from December to May, this ray is found over the middle and outer parts of the continental shelf from Cape Hatteras in North Carolina to Florida, with larger rays occurring further south than smaller ones. In the spring, the population moves north of the Cape and towards the coast into bays, inlets, and saltier estuaries, though preserving the north-south gradient of body sizes. A similar migration, from shallow coastal waters in summer to deeper offshore waters in winter, apparently occurs in the Mediterranean.[7] Pregnant females tend to be found apart from other individuals.[7][12]

Description

The roughtail stingray has a diamond-shaped pectoral fin disk 1.2–1.3 times as wide as long, with straight to gently sinuous margins, rather angular outer corners, and a moderately long, obtuse snout. The eyes are proportionally smaller than other stingrays in its range and immediately followed by larger spiracles. There is a curtain of skin between the nostrils with a finely fringed posterior margin. The mouth is bow-shaped with a row of six papillae (nipple-like structures) across the floor. The seven upper and 12–14 lower tooth rows at the center are functional, though the total number of tooth rows is much greater. The teeth are arranged with a quincunx pattern into flattened surfaces; each has a tetragonal base with a blunt crown in juveniles and females, and a pointed cusp in adult males.[10][13]

The pelvic fins have nearly straight margins and angular tips. The tail is long and whip-like, measuring some 2.5 times the length of the disc. A long, saw-toothed spine is placed atop the tail at around half a disc length back from the tail base; sometimes one or two replacement spines are also present in front of the existing one. Behind the spine, there is a long ventral fin fold that is much lower than that of the southern stingray. Individuals under 46–48 cm (18–19 in) across have completely smooth skin. Larger rays develop increasing numbers of distinctive tubercles or bucklers (flat-based thorns) over the middle of the back from the snout to the tail base, as well as dorsal and lateral rows of thorns on the tail. The bucklers vary in size, with the largest of equal diameter to the eye, and may bear up to three thorns each. This species is a uniform dark brown or olive above, and off-white below without dark fin margins.[10][13] Among the largest members of its family, the roughtail stingray can reach 2.6 m (8.5 ft) across, 4.0 m (13.1 ft) long, and 300 kg (660 lb) in weight.[14] Females grow larger than males.[12]

Biology and ecology

The roughtail stingray is reportedly not highly active, spending much time buried in the sediment. It is a generalist predator whose diet generally reflects the most available prey in its environment.[7] It mainly captures prey off the bottom, but also opportunistically takes free-swimming prey.[15] A variety of invertebrates, as well as bony fishes such as sand lance and scup, are known to be consumed.[2][7] Off Massachusetts, the main prey are crabs (Cancer), bivalves (Mya), gastropods (Polinices), squid (Loligo) and annelid worms.[10] In Delaware Bay, most of its diet consists of the shrimp Cragon septemspinosa and the blood worm Glycera dibranchiata; the overall dietary composition there is nearly identical to that of bluntnose stingrays (D. say) that share the bay.[15] The shrimp Upogebia affinis is a major food source off Virginia.[1] Off Florida, crustaceans (Rananoides, Ovalipes, Sicyonia brevirostris, and Portunus) and polychaete worms are the most important prey.[7]

Sharks and other large fishes, in particular the great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran), prey upon the roughtail stingray.[2] The live sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates) is sometimes found attached to its body.[16] Known parasites of this species include the tapeworms Acanthobothrium woodsholei,[17] Anthocephalum centrurum,[18] Lecanicephalum sp.,[19] Oncomegas wageneri,[20] Polypocephalus sp.,[19] Pterobothrium senegalense,[21] and Rhinebothrium maccallumi,[22] the monogenean Dendromonocotyle centrourae,[23] and the leech Branchellion torpedinis.[24]

Like other stingrays, the roughtail stingray is aplacental viviparous: the developing embryo is initially sustained by yolk and later by histotroph ("uterine milk", containing proteins, lipids, and mucus) delivered by the mother through finger-like projections of the uterine epithelium called "trophonemata". Only the left ovary and uterus are functional in adult females. Off the eastern United States, reproduction occurs on an annual cycle with mating in winter and early spring. After a gestation period of 9–11 months, females give birth to 4–6 (typically five) young in fall or early winter. The newborns measure 34–37 cm (13–15 in) across.[7] Off North Africa, birthing occurs in June and December, indicating either that females bear two litters per year with a four-month gestation period, or that there are two cohorts of females bearing one litter per year with a ten-month gestation period. The newborns are much smaller than those in the northwestern Atlantic at 8–13 cm (3.1–5.1 in) across, which would be consistent with a shorter gestation period.[12] The size at maturity also differs between the two regions: off the eastern United States males and females mature at 130–150 cm (51–59 in) and 140–160 cm (55–63 in) across respectively, while off North Africa males and females mature at 80 cm (31 in) and 66–100 cm (26–39 in) across respectively.[7][12]

Human interactions

With its large size and long, venomous spine, the roughtail stingray can inflict a severe wound and can be very dangerous for fishers to handle. However, it is not aggressive and usually occurs too deep to be encountered by beachgoers.[10] It has been reported to damage farmed shellfish beds. The pectoral fins or "wings" are sold for human consumption fresh, smoked, or dried and salted; the rest of the ray may also be processed to obtain fishmeal and liver oil.[6] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the roughtail stingray as of Least Concern worldwide, while noting that as a large, slow-reproducing species it is susceptible to population depletion.[1]

In the northwestern Atlantic, the roughtail stingray is listed under Least Concern; it is not targeted or utilized by commercial fisheries, though inconsequential numbers are captured incidentally in trawls and on demersal longlines.[1] Historically, it was sometimes ground up for fertilizer.[10] In the Mediterranean, intensive fishing occurs in the habitat of the roughtail stingray, and it is caught incidentally by artisanal and commercial fishers using trawls, longlines, gillnets, and handlines. Though no specific data is available on this species, declines of other species and its intrinsic susceptibility to depletion have led it to be assessed as Near Threatened in the region. In the southwestern Atlantic, the roughtail stingray and other large rays are heavily fished using demersal trawls, gillnets, longlines, and hook-and-line; this fishing pressure is liable to increase due to growing commercial interest in using large stingrays for minced fish products. Anecdotal reports suggest that landings of this species are decreasing, leading to a regional assessment of Near Threatened.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Rosa, R.S., M. Furtado, F. Snelson, A. Piercy, R.D. Grubbs, F. Serena and C. Mancusi (2007). Dasyatis centroura. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on March 23, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Eagle, D. Biological Profiles: Roughtail Stingray. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on March 23, 2009.

- ^ Mitchill, S.L. (1815). "The fishes of New York described and arranged". Transactions of the Literary and Philosophical Society of New York 1: 355–492. http://books.google.com/?id=6XwTAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA355&q=.

- ^ Fitch, J.E. and R.J. Lavenberg (1971). Marine Food and Game Fishes of California. University of California Press. p. 11. ISBN 0520018311.

- ^ Eschmeyer, W.N. (ed.) centroura, Raja. Catalog of Fishes electronic version (February 19, 2010). Retrieved on March 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Dasyatis centroura" in FishBase. March 2009 version.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Struhsaker, P. (April 1969). "Observations on the Biology and Distribution of the Thorny Stingray, Dasyatis Centroura (Pisces: Dasyatidae)". Bulletin of Marine Science 19 (2): 456–481. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/umrsmas/bullmar/1969/00000019/00000002/art00014.

- ^ a b Rosenberger, L.J.; Schaefer, S. A. (August 6, 2001). "Phylogenetic Relationships within the Stingray Genus Dasyatis (Chondrichthyes: Dasyatidae)". Copeia 2001 (3): 615–627. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001[0615:PRWTSG]2.0.CO;2. http://pinnacle.allenpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1643/0045-8511(2001)001%5B0615:PRWTSG%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

- ^ de Almeida Leao Vaz, L., C.R. Porto Carreiro, L.R. Goulart-Filho and M.A.A. Furtado-Neto (2006). "Phylogenetic relationships in rays (Dasyatis, Elasmobranchii) from Ceara State, Brazil". Arquivos de Ciencias do Mar 39: 86–88.

- ^ a b c d e f Bigelow, H.B. and W.C. Schroeder (1953). Fishes of the Western North Atlantic, Part 2. Sears Foundation for Marine Research, Yale University. pp. 352–362.

- ^ Hennemann, R.M. (2001). Sharks & Rays: Elasmobranch Guide of the World. IKAN-Unterwasserarchiv. p. 252. ISBN 3925919333.

- ^ a b c d Capapé, C. (1993). "New data on the reproductive biology of the thorny stingray, Dasyatis centroura (Pisces: Dasyatidae) from off the Tunisian coasts". Environmental Biology of Fishes 38 (1–3): 73–40. doi:10.1007/BF00842905. http://www.springerlink.com/content/r35875104p69u541/.

- ^ a b McEachran, J.D. and Fechhelm, J.D. (1998). Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico: Myxiniformes to Gasterosteiformes. University of Texas Press. p. 175. ISBN 0292752067.

- ^ Dulcic, J., I. Jardas, V. Onofri and J. Bolotin (August 2003). "The roughtail stingray Dasyatis centroura (Pisces : Dasyatidae) and spiny butterfly ray Gymnura altavela (Pisces : Gymnuridae) from the southern Adriatic". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 83 (4): 871–872. doi:10.1017/S0025315403007926h. http://journals.cambridge.org/production/action/cjoGetFulltext?fulltextid=170022.

- ^ a b Hess, P.W. (June 19, 1961). "Food Habits of Two Dasyatid Rays in Delaware Bay". Copeia (American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists) 1961 (2): 239–241. doi:10.2307/1440016. JSTOR 1440016.

- ^ Schwartz, F.J. (2004). "Five species of sharksuckers (family Echeneidae) in North Carolina". Journal of the North Carolina Academy of Science 120 (2): 44–49.

- ^ Goldstein, R.J. (October 1964). "Species of Acanthobothrium (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea) from the Gulf of Mexico". The Journal of Parasitology (The American Society of Parasitologists) 50 (5): 656–661. doi:10.2307/3276123. JSTOR 3276123.

- ^ Ruhnke, T.R. (1994). "Resurrection of Anthocephalum Linton, 1890 (Cestoda: Tetraphyllidea) and taxonomic information on five proposed members". Systematic Parasitology 29 (3): 159–176. http://www.springerlink.com/content/g22m250139580p54/.

- ^ a b Timothy, D., J. Littlewood and R.A. Bray (2001). Interrelationships of the Platyhelminthes. CRC Press. p. 153. ISBN 0748409033.

- ^ Toth, L.M., R.A. Campbell and G.D. Schmidt (July 1992). "A revision of Oncomegas Dollfus, 1929 (Cestoda: Trypanorhyncha: Eutetrarhynchidae), the description of two new species and comments on its classification". Systematic Parasitology 22 (3): 167–187. doi:10.1007/BF00009664. http://www.springerlink.com/content/q7121h414245tk34/.

- ^ Campbell, R.A. and I. Beveridge (1996). "Revision of the family Pterobothriidae Pintner, 1931 (Cestoda: Trypanorhyncha)". Invertebrate Taxonomy 10 (3): 617–662. doi:10.1071/IT9960617. http://www.publish.csiro.au/?paper=IT9960617.

- ^ Campbell, R.A. (June 1970). "Notes on Tetraphyllidean Cestodes from the Atlantic Coast of North America, with Descriptions of Two New Species". The Journal of Parasitology (The American Society of Parasitologists) 56 (3): 498–508. doi:10.2307/3277613. JSTOR 3277613.

- ^ Cheung, P. and W. Brent (1993). "A new dendromonocotylinid (monogenean) from the skin of the roughtail stingray, Dasyatis centroura Mitchill". Journal of Aquariculture and Aquatic Sciences 6 (3): 63–68.

- ^ Sawyer, R.T., A.R. Lawler and R.M. Oversrteet (December 1975). "Marine leeches of the eastern United States and the Gulf of Mexico with a key to the species". Journal of Natural History 9 (6): 633–667. doi:10.1080/00222937500770531. http://www.informaworld.com/index/J58123G4546V6008.pdf.

External links

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Dasyatis

- Animals described in 1815

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.