- Short-tail stingray

-

Short-tail stingray

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Chondrichthyes Subclass: Elasmobranchii Order: Myliobatiformes Family: Dasyatidae Genus: Dasyatis Species: D. brevicaudata Binomial name Dasyatis brevicaudata

(F. W. Hutton, 1875)

Range of the short-tail stingray[2] Synonyms Trygon brevicaudata F. W. Hutton, 1875

Trygon schreineri Gilchrist, 1913The short-tail stingray or smooth stingray (Dasyatis brevicaudata) is a common species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae. It occurs off southern Africa, typically offshore at a depth of 180–480 m (590–1,570 ft), and off southern Australia and New Zealand, from the intertidal zone to a depth of 156 m (512 ft). It is mostly bottom-dwelling in nature and can be found across a range of habitats from estuaries to reefs, but also frequently swims into open water. The largest stingray in the world, this heavy-bodied species grows upwards of 2.1 m (6.9 ft) across and 350 kg (770 lb) in weight. Its plain-colored, diamond-shaped pectoral fin disc is characterized by a lack of dermal denticles even in adults, and white pores beside the head on either side. Its tail is usually shorter than the disc and thick at the base, with a midline row of large thorns in front of the stinging spine and dorsal and ventral fin folds behind.

The diet of the short-tail stingray consists of invertebrates and bony fishes, including burrowing and midwater species. It tends to remain within a relatively limited area throughout the year, preferring deeper waters during the winter, and is not known to perform long migrations. Large aggregations of rays form seasonally at certain locations, such as in the summer at the Poor Knight Islands off New Zealand. Both birthing and mating have been documented within the aggregations at Poor Knights. This species is aplacental viviparous, with the developing embryos sustained by histotroph ("uterine milk") produced by the mother; the litter size is 6–10. The short-tail stingray is not aggressive but is capable of inflicting a potentially lethal wound with its long, venomous sting. It is caught incidentally by commercial and recreational fisheries throughout its range, usually surviving to be released. Because its population does not appear threatened by human activity, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed it under Least Concern.

Contents

Taxonomy

The original description of the short-tail stingray was made by Frederick Wollaston Hutton, Curator of the Otago Museum, from a female specimen 1.2 m (3.9 ft) across caught off Dunedin in New Zealand. He published his account in an 1875 issue of the scientific journal Annals and Magazine of Natural History, in which he named the new species Trygon brevicaudata, derived from the Latin brevis ("short") and cauda ("tail"). Subsequent authors have assigned this species to the now-obsolete genus Bathytoshia, and then to Dasyatis.[3][4] The short-tail stingray may also be referred to as giant black ray, giant stingray, New Zealand short-tail stingaree, Schreiners ray, short-tailed stingaree, shorttail black stingray, and smooth short-tailed stingray.[5] It is closely related to the similar-looking but smaller pitted stingray (Dasyatis matsubarai) of the northwestern Pacific.[6]

Distribution and habitat

The short-tail stingray is common and widely distributed in the temperate waters of the Southern Hemisphere. Off southern Africa, it has been reported from Cape Town in South Africa to the mouth of the Zambezi River in Mozambique. Along the southern Australian coast, it is found from Shark Bay in Western Australia to Maroochydore in Queensland, including Tasmania. In New Zealand waters, it occurs off North Island and the Chatham Islands, and rarely off South Island and the Kermadec Islands. Records from northern Australia and Thailand likely represent misidentifications of Himantura fai and D. matsubarai respectively.[2][4] Over the past few decades, its range and numbers off southeastern Tasmania have grown, possibly as a result of climate change.[7]

Off southern Africa, the short-tail stingray is rare in shallow water and most often found over offshore banks at a depth of 180 to 480 m (590 to 1,570 ft). On the other hand, off Australia and New Zealand it is found from the intertidal zone to no deeper than 156 m (512 ft).[1] Australian and New Zealand rays are most abundant in the shallows during the summer. A tracking study conducted on two New Zealand rays suggests that they shift to deeper waters during the winter, but do not undertake long-distance migrations.[8] The short-tail stingray is mainly bottom-dwelling in nature, inhabiting a variety of environments including brackish estuaries, sheltered bays and inlets, sandy flats, rocky reefs, and the outer continental shelf.[1][6] However, it also makes regular forays upward into the middle of the water column.[8]

Description

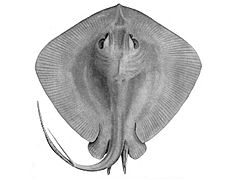

Heavily built and characteristically smooth, the pectoral fin disc of the short-tail stingray has a rather angular, rhomboid shape and is slightly wider than long. The leading margins of the disc are very gently convex, and converge on a blunt, broadly triangular snout. The eyes are small and immediately followed by much larger spiracles. The widely spaced nostrils are long and narrow; between them is a short, skirt-shaped curtain of skin with a fringed posterior margin. The modestly sized mouth has an evenly arched lower jaw, prominent grooves at the corners, and 5–7 papillae (nipple-like structures) on the floor. Additional, tiny papillae are scattered on the nasal curtain and outside the lower jaw. The teeth are arranged with a quincunx pattern into flattened surfaces; each tooth is small and blunt, with a roughly diamond-shaped base. There are 45–55 tooth rows in either jaw. The pelvic fins are somewhat large and rounded at the tips.[2][9]

The tail is usually shorter than the disc and bears one, sometimes two serrated stinging spines on the upper surface, about halfway along its length. It is broad and flattened until the base of the sting; after, it tapers rapidly and there is a prominent ventral fin fold running almost to the sting tip, as well as a low dorsal ridge. Dermal denticles are only found on the tail, with at least one thorn appearing on the tail base by a disc width of 45 cm (18 in). Adults have a midline row of large, backward-pointing, spear-like thorns or flattened tubercles in front of the sting, as well as much smaller, conical thorns behind the sting covering the tail to the tip. The dorsal coloration is grayish brown, darkening towards the tip of the tail and above the eyes, with a line of white pores flanking the head on either side. The underside is whitish, darkening towards the fin margins and beneath the tail.[2][9] Albino individuals have been reported.[10] The short-tail stingray is the largest stingray species,[1] known to reach at least 2.1 m (6.9 ft) in width, 4.3 m (14 ft) in length, and 350 kg (770 lb) in weight. Reliable observers off New Zealand have reported sighting individuals almost 3 m (10 ft) across.[1] Mature females are about a third larger than mature males.[6]

Biology and ecology

The short-tail stingray is usually slow-moving but can achieve sudden bursts of speed, flapping its pectoral fins with enough force to cavitate the water and create an audible "bang".[11] It is known to form large seasonal aggregations; a well-known example occurs every summer (January to April) at the Poor Knights Islands off New Zealand, particularly under the rocky archways. In some areas it moves with the rising tide into very shallow water.[8][12] Individual rays tend to stay inside a relatively small home range with a radius of under 25 km (16 mi).[8] Captive experiments have shown it capable of detecting magnetic fields via its electroreceptive ampullae of Lorenzini, which in nature may be employed for navigation.[13]

The short-tail stingray forages for food both during the day and at night.[14] It feeds primarily on benthic bony fishes and invertebrates, such as molluscs and crustaceans. The lateral line system on its underside allows it to detect the minute water jets produced by buried bivalves and spoon worms, which are then extracted via suction; the excess water is expelled through the spiracles.[15] Fishes and invertebrates from open water, including salps and hyperiid amphipods, are also eaten in significant quantities.[8] Off South Africa, this ray has been observed patrolling the egg beds of the chokka squid (Loligo vulgaris reynaudii) during mass spawnings, capturing squid that descend to the bottom to spawn.[16] The short-tail stingray has few predators due to its size; these include the copper shark (Carcharhinus brachyurus), the smooth hammerhead (Sphryna zygaena), the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), and the killer whale (Orcinus orca).[4][8] When threatened, it raises its tail warningly over its back like a scorpion.[2] Smaller fishes have been observed using swimming rays for cover while hunting their own prey.[11] Known parasites of this species include the nematode Echinocephalus overstreeti,[17] and the monogeneans Heterocotyle tokoloshei and Dendromonocotyle sp.[18][19]

Life history

The summer aggregations of the short-tail stingray at the Poor Knights Islands seem to at least partly serve a reproductive purpose, as both mating and birthing have been observed among the gathered rays. Courtship and mating take place in mid-water, and it has been speculated that the rising current flowing continuously through the narrow archways aids the rays in maintaining their position.[6][11] Each receptive female may be followed by several males, who attempt to bite and grip her disc. One or two males may be dragged by the female for hours before she accedes; the successful male flips upside-down beneath her, inserting one of his claspers into her vent and rhythmically waving his tail from side to side. Copulation lasts 3–5 minutes.[8][12] Females in captivity have been observed mating with up to three different males in succession.[20]

Like other stingrays, the short-tail stingray is aplacental viviparous: once the developing embryos exhaust their yolk supply, they are provisioned with histotroph ("uterine milk", enriched with proteins, lipids and mucus) produced by the mother and delivered through specialized extensions of the uterine epithelium called "trophonemata".[4] Females bear litters of 6–10 pups in the summer; males appear to assist in the process by nudging the female's abdomen with their snouts. Females are ready to mate again shortly after giving birth.[2][6][12] Newborns measure 32–36 cm (13–14 in) across.[1][2]

Human interactions

Curious and unaggressive, the short-tail stingray may approach humans and can be trained to be hand-fed.[21] At Hamelin Bay in Western Australia, many short-tail stingrays, thorntail stingrays (D. thetidis), and Australian bull rays (Myliobatis australis) regularly gather to be hand-fed fish scraps; the number of visitors has steadily increased in recent years, and there is interest in developing the site as a permanent tourist attraction.[22] However, if startled or harassed this species is capable of inflicting a serious, even fatal wound with its sting. The sting can measure over 30 cm (12 in) long and penetrate most types of footwear, including kevlar bootees; its mucous sheath contains a toxin that causes necrosis. The most dangerous injuries involve damage to a vital organ, massive blood loss, and/or secondary septicemia or tetanus. There have been cases where a startled ray had jumped out of the water and pierced a wader's chest cavity. This species is responsible for the majority of stingray injuries off New Zealand.[23][24]

Throughout its range, the short-tail stingray is caught incidentally by various commercial fisheries using trawls, Danish and purse seines, longlines and set lines, and drag and set nets. It is also caught by recreational fishers using hook-and-line (from boats or the shore), spears, and harpoons. Most individuals caught are released alive; often fishers cut off their tails beforehand for safety, though this practice does not seem to have a significant impact on the rays' long-term survival. Sport fishers occasionally keep captured rays for meat or angling competitions; a small number are also kept for display in public aquariums,[1] and it has reproduced in captivity.[12] As it survives fishing activities well and remains common throughout its range, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the short-tail stingray as Least Concern. Within most of this species' range off New Zealand, targeting it commercially is prohibited.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Duffy, C. and L. Paul (2003). "Dasyatis brevicaudata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/41796. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Last, P.R. and J.D. Stevens (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 434–435. ISBN 0674034112.

- ^ Hutton, F. W. (November 1, 1875). "Descriptions of new species of New Zealand fish". Annals and Magazine of Natural History (Series 4) 16 (95): 313–317. http://books.google.com/?id=0MtMAAAAYAAJ&lpg=PA313&dq=%22Descriptions%20of%20new%20species%20of%20New%20Zealand%20fish%22&pg=PA317#v=onepage&q=%22Descriptions%20of%20new%20species%20of%20New%20Zealand%20fish%22&f=false.

- ^ a b c d Bester, C.. "Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department: Short-tail Stingray". Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/Gallery/Descript/ShorttailStingray/ShorttailStingray.html. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2010). "Dasyatis brevicaudata" in FishBase. September 2010 version.

- ^ a b c d e Hennemann, R.M. (2001). Sharks & Rays: Elasmobranch Guide of the World. IKAN-Unterwasserarchiv. pp. 195–199, 254.

- ^ Last, P.R., W.T. White, D.C. Gledhill, A.J. Hobday, R. Brown, G.J. Edgar, and G. Pecl (July 23, 2010). "Long-term shifts in abundance and distribution of a temperate fish fauna: a response to climate change and fishing practices". Global Ecology and Biogeography 20: 58. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00575.x. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00575.x/full.

- ^ a b c d e f g Le Port, A., T. Sippel and J.C. Montgomery (May 9, 2008). "Observations of mesoscale movements in the short-tailed stingray, Dasyatis brevicaudata from New Zealand using a novel PSAT tag attachment method". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 359 (2): 110–117. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2008.02.024. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0022098108001299.

- ^ a b Garrick, J.A.F. (June 1954). "Studies on New Zealand Elasmobranchii. Part II. A Description of Dasyatis brevicaudatus (Hutton), Batoidei, with a review of records of the species outside New Zealand". Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand 82 (1): 189–198. http://rsnz.natlib.govt.nz/volume/rsnz_82/rsnz_82_01_002130.pdf.

- ^ Talent, L.G. (1973). "Albinism in embryo gray smoothhound sharks, Mustelus californicus, from Elkhorn Slough, Monterey Bay, California". Copeia 1973 (3): 595–597. doi:10.2307/1443129. JSTOR 1443129. (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Anthoni, J.F.. "Poor Knights marine reserve: The mystery of the social sting rays". Sea Friends. http://www.seafriends.org.nz/issues/res/pk/stingrays.htm. Retrieved September 15, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Michael, S.W. (1993). Reef Sharks & Rays of the World. Sea Challengers. p. 83. ISBN 0930118189.

- ^ Molteno, T.C.A. and W.L. Kennedy (2009). "Navigation by Induction-Based Magnetoreception in Elasmobranch Fishes". Journal of Biophysics 2009: 1. doi:10.1155/2009/380976. PMC 2814134. PMID 20130793. http://www.hindawi.com/journals/jbp/2009/380976.html.

- ^ Svane, I., S. Roberts and T. Saunders (April 2008). "Fate and consumption of discarded by-catch in the Spencer Gulf prawn fishery, South Australia". Fisheries Research 90 (1–3): 158–169. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2007.10.008. http://www.reefwatch.asn.au/prawns/PDF/Svane_etal_2008.pdf.

- ^ Montgomery, J. and E. Skipworth (December 9, 1997). "Detection of Weak Water Jets by the Short-Tailed Stingray Dasyatis brevicaudata (Pisces: Dasyatidae)". Copeia 1997 (4): 881–883. doi:10.2307/1447310. JSTOR 1447310. (subscription required)

- ^ Smale, M., W. Sauer and M. Roberts (2001). "Behavioural interactions of predators and spawning chokka squid off South Africa: towards quantification". Marine Biology 139 (6): 1095–1105. doi:10.1007/s002270100664. http://www.springerlink.com/content/3l7g1xa27aacmd6p/.

- ^ Moravec, F. and J. Justine (2006). "Three nematode species from elasmobranchs off New Caledonia" (PDF). Systematic Parasitology 64 (2): 131–145. doi:10.1007/s11230-006-9034-x. PMID 16773474. http://horizon.documentation.ird.fr/exl-doc/vcc/2006/07/010035677.pdf.

- ^ Vaughan, D.B. and L.A. Chisholm (2010). "Heterocotyle tokoloshei sp. nov. (Monogenea, Monocotylidae) from the gills of Dasyatis brevicaudata (Dasyatidae) kept in captivity at Two Oceans Aquarium, Cape Town, South Africa: Description and notes on treatment". Acta Parasitologica 55 (2): 108–114. doi:10.2478/s11686-010-0018-2. http://www.springerlink.com/content/0285343946185424/.

- ^ Chisholm, L.A., I.D. Whittington and A.B.P. Fischer (2004). "A review of Dendromonocotyle (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from the skin of stingrays and their control in public aquaria". Folia Parasitologica 51 (2–3): 123–130. PMID 15357391. http://www.paru.cas.cz/folia/pdfs/showpdf.php?pdf=20704.

- ^ Michael, S.W. (2001). Aquarium Sharks & Rays. T.F.H. Publications. p. 217. ISBN 18900087572.

- ^ Aitken, K.. "Smooth Stingray (Dasyatis brevicaudata) Dasyatidae.". Marine Themes Stock Library. http://www.marinethemes.com/smoothray.html. Retrieved Retrieved on September 15, 2010.

- ^ Lewis, A. and D. Newsome (2003). "Planning for Stingray Tourism at Hamelin Bay, Western Australia: the Importance of Stakeholder Perspectives". International Journal of Tourism Research 5 (5): 331–346. doi:10.1002/jtr.442.

- ^ Adams, S. (2007). "Bites and Stings: Marine Stings". Journal of the Accident and Medical Practitioners Association (JAMPA) 4 (1). http://www.ampa.co.nz/Adams_Bites%20and%20Stings%20Marine%20stings%20FINAL.pdf.

- ^ Slaughter, R.J., D. Michael, G. Beasley, B.S Lambie, and L.J. Schep (February 27, 2009). "New Zealand's venomous creatures". Journal of the New Zealand Medical Association 122 (1290). https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/122-1290/3494/.

External links

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Dasyatis

- Animals described in 1875

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.