- Celts (modern)

-

A Celtic identity emerged in the "Celtic" nations of Western Europe, following the identification of the native peoples of the Atlantic fringe as "Celts" by Edward Lhuyd in the 18th century and during the course of the 19th-century Celtic Revival, taking the form of ethnic nationalism particularly within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, where the Irish Home Rule Movement resulted in the secession of the Irish Free State in 1922. After World War II, the focus of the Celticity movement shifted to linguistic revival and protectionism, e.g. with the foundation of the Celtic League in 1961, dedicated to preserving the surviving Celtic languages.[1]

Since the Enlightenment, the term Celtic has been applied to a wide variety of peoples and cultural traits present and past. Today, Celtic is often used to describe people of the Celtic nations (the Bretons, the Cornish, the Irish, the Manx people, the Scots and the Welsh) and their respective cultures and languages.[2] Except for the Bretons (if discounting Norman & Channel Islander connections), all groups mentioned have been subject to strong Anglicisation since the Early Modern period, and are hence are also described as participating in an Anglo-Celtic macro-culture. By the same token, the Bretons have been subject to strong Frenchification since the Early Modern period, and can similarly be described as participating in a Franco-Celtic macro-culture.

Less common is the assumption of Celticity for European cultures deriving from Continental Celtic roots (Gauls and Celtiberians). These were either Romanised or Germanised much earlier, before the Early Middle Ages. Nevertheless, Celtic origins are sometimes implied for continental groups such as the Asturians, Galicians, Portuguese, French, Swiss, Alpine Italians, Germans,[3] or Austrians. The names of Belgium and the Aquitaine hark back to Gallia Belgica and Gallia Aquitania, respectively, in turn named for the Belgae and the Aquitani.[4][5] The Latin name of the Swiss Confederacy, Confoederatio Helvetica, harks back to the Helvetii, the name of Galicia to the Gallaeci and the Auvergne of France to the Averni.

Contents

Celtic revival and Romanticism

Further information: Celtic Revival'Celt' has been adopted as a label of self-identification by a variety of peoples at different times. 'Celticity' can refer to the inferred links between them.

During the 19th century, French nationalists gave a privileged significance to their descent from the Gauls. The struggles of Vercingetorix were portrayed as a forerunner of the 19th-century struggles in defence of French nationalism, including the wars of both Napoleons (Napoleon I of France and Napoleon III of France). Basic French history textbooks emphasised the ways in which Gauls could be seen as an example of cultural assimilation; however, the notion that French history textbooks commonly began with the famous words "Nos ancêtres les Gaulois..." ("Our ancestors the Gauls...") is not supported in fact.[6] A similar use of Celticity for 19th century nationalism was made in Switzerland, when the Swiss were seen to originate in the Celtic tribe of the Helvetii, a link still found in the official Latin name of Switzerland, Confœderatio Helvetica, the source of the nation code CH and the name used on postage stamps (Helvetia).

Before the advance of Indo-European studies, philologists established that there was a relationship between the Goidelic and Brythonic languages, as well as a relationship between these languages and the extinct Celtic languages such as Gaulish, spoken in classical times. The terms Goidelic and Brythonic were first used to describe the two Celtic language families by Edward Lhuyd in his 1707 study and, according to the National Museum Wales, during that century "people who spoke Celtic languages were seen as Celts."[2]

At the same time, there was also a tendency to play up alternative heritages in the British Isles at certain times. For example, in the Isle of Man, in the Victorian era, the Viking heritage was emphasised, and in Scotland, both Norse and Anglo-Saxon heritage was emphasised.

A romantic image of the Celt as noble savage was cultivated by the early William Butler Yeats, Lady Gregory, Lady Charlotte Guest, Lady Llanover, James Macpherson, Chateaubriand, Théodore Hersart de la Villemarqué and the many others influenced by them. This image coloured not only the English perception of their neighbours on the so-called "Celtic fringe" (compare the stage Irishman), but also Irish nationalism and its analogues in the other Celtic-speaking countries. Among the enduring products of this resurgence of interest in a romantic, pre-industrial, brooding, mystical Celticity are Gorseddau, the revival of the Cornish language,[7][8] and the revival of the Gaelic games.

Contemporary Celtic identity

The modern Celtic groups' distinctiveness as national, as opposed to regional, minorities has been periodically recognised by major British papers. For example, a Guardian editorial in 1990 pointed to these differences, and said that they should be constitutionally recognised:

Smaller minorities also have equally proud visions of themselves as irreducibly Welsh, Irish, Manx or Cornish. These identities are distinctly national in ways which proud people from Yorkshire, much less proud people from Berkshire will never know. Any new constitutional settlement which ignores these factors will be built on uneven ground.[9]

The Republic of Ireland, on surpassing Britain's GDP per capita in the 1990s for the first time in centuries, was given the moniker "Celtic tiger". Thanks in part to agitation on the part of Cornish regionalists, Cornwall was able to obtain Objective One funding from the European Union. Scotland and Wales obtained agencies like the Welsh Development Agency, and Scottish and Welsh Nationalists have recently supported the institution of the Scottish Parliament and National Assembly for Wales. More broadly, a distinct identity in opposition to that of the metropolitan capitals has been forged and taken strong root.

These latter evolutions have proceeded hand in hand with the growth of a pan-Celtic or inter-Celtic dimension, seen in many organisations and festivals operating across various Celtic countries. Celtic studies departments at many universities in Europe and beyond, have studied the various ancient and modern Celtic languages and associated history and folklore under one roof.

Some of the most vibrant aspects of modern Celtic culture are music, song and festivals. Under the Music and Festivals sections below, the full richness of these aspects that have captured the world's attention are outlined.[10]

Sports such as Hurling, Gaelic Football and Shinty are seen as being Celtic.

The USA has also taken part in discussions of modern Celticity. For example, Virginia Senator James H. Webb, in his 2004 book Born Fighting–How the Scots-Irish Shaped America, controversially asserts that the early "pioneering" immigrants to North America were of Scots-Irish origins. He goes on to argue that their distinct Celtic traits (loyalty to kin, mistrust of governmental authority, and military readiness), in contrast to the Anglo-Saxon settlers, helped construct the modern American identity. Irish Americans also played an important role in the shaping of 19th-century Irish republicanism through the Fenian movement, the development of a discourse of the Great Hunger as a British atrocity, and so on.

Celtic nations

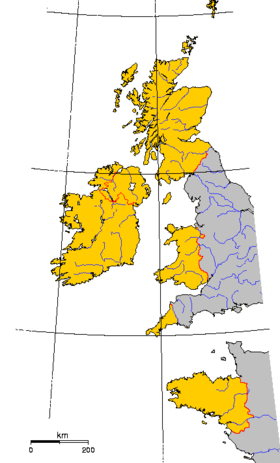

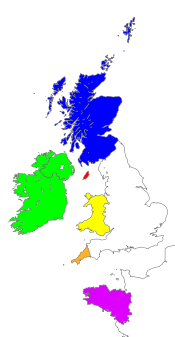

Main article: Celtic nationsSix nations tend to be most associated with a modern Celtic identity, and are considered 'the Celtic nations'.

It is these 'Six Nations' that (alone) are considered Celtic by the Celtic League and the Celtic Congress amongst others.[11][12] These organisations ascribe to a definition of Celticity based mainly upon language. In the aforementioned six regions, Celtic languages have survived and continue to be used to varying degrees in Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Isle of Man, Cornwall and Brittany.[13]

A number of activists on behalf of other regions/nations have also sought recognition as modern Celts, reflecting the wide diffusion of ancient Celts across Europe. Of these, the most prominent are Galicia and Asturias.

In neither Galicia / Northern Portugal nor Asturias has a Celtic language survived, and as such both fall outside of the litmus test used by the Celtic League, and the Celtic Congress. Nevertheless, many organisations organised around Celticity consider that Galicia / Northern Portugal (Douro, Minho and Tras-os-Montes) and Asturias "can claim a Celtic cultural or historic heritage".[14] These claims to Celticity are rooted in the long[15] historical existence of Celts in these regions and ethnic connections to other Atlantic Celtic peoples[16][17][18](see Celtiberians, Celtici and Castro culture). In 2009, the Gallaic Revival Movement, sponsored by the Liga Celtiga Galaica (the Galician Celtic League), claimed to be reconstructing the Q-Celtic Gallaic language based on the Atebivota Dictionary and Old Celtic Dictionary compiled by Vincent F. Pintado.[19][20][21][22]

Elements of Celtic music, dance, and folklore can be found within England (e.g. Yan Tan Tethera, Well dressing, Halloween), and the Cumbric language survived until the collapse of the Kingdom of Strathclyde in about 1018.[23] England as a whole comprises many distinct regions, and some of these regions, such as Cumbria, Lancashire, Western Yorkshire[24] and Devon,[25] can claim more Celtic heritage than others. In 2009, it was claimed that revival of the Cumbric language was being attempted in the Cumberland area of England.[24][26]

Similarly, in France outside of Brittany, in the Auvergne (province) chants are sung around bonfires remembering a Celtic god.[27]

Migration from Celtic countries

Main article: Celtic diasporaA significant portion of the populations of the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand is composed of people whose ancestors were from one of the "Celtic nations". This concerns the Irish diaspora most significantly (see also Irish American), but to a lesser extent also the Welsh diaspora and the Cornish diaspora.

There are three areas outside Europe with communities of Celtic language speakers:

- the province of Chubut in Patagonia with Welsh-speaking Argentinians (known as Y Wladfa)

- Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia with Scottish Gaelic-speaking Canadians

- southeast Newfoundland with Irish-speaking Canadians.

The most common mother-tongue amongst the Fathers of Confederation which saw the formation of Canada was Gaelic.[28] There is a movement in Cape Breton for a separate province in Canada, as espoused by the Cape Breton Labour Party and others.

In some former British colonies, or particular regions within them, the term Anglo-Celtic has emerged as a descriptor of an ethnic grouping. In particular, Anglo-Celtic Australian is a term comprising about 80% of the population.[29]

Music

Main article: Celtic musicFurther information: List of Celtic choirs(see External links - Music at end of article for examples of modern Celtic music)

Gaelic singer Karen Matheson OBE with Capercaillie at Celtic Rock 2007

Gaelic singer Karen Matheson OBE with Capercaillie at Celtic Rock 2007

The claim that distinctly Celtic styles of music exist was made during the nineteenth century, and was associated with the revival of folk traditions and pan-Celtic ideology. The Welsh anthem "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau" was adopted as a pan-Celtic anthem.[30] Though there are links between Scots Gaelic and Irish Gaelic folk musics, very different musical traditions existed in Wales and Brittany. Nevertheless, Gaelic styles were adopted as typically Celtic even by Breton revivalists such as Paul Ladmirault.[31]

Celticism came to be associated with the bagpipe and the harp. The roots revival, applied to Celtic music, has brought much inter-Celtic cross-fertilisation, as, for instance, the revival by Welsh musicians of the use of the mediaeval Welsh bagpipe under the influence of the Breton binioù, Irish uillean pipes and famous Scottish pipes,[32] or the Scots have revived the bodhran from Irish influence.[33] Charles le Goffic introduced the Scottish Highland pipes to Brittany.

Unaccompanied or A cappella [34] styles of singing are performed across the modern Celtic world due to the folk music revival, popularity of Celtic choirs, world music, scat singing [35] and hip hop rapping in Celtic languages.[36][37] Traditional rhythmic styles used to accompany dancing and now performed are Puirt a beul from Scotland, Ireland, and Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Sean-nós song from Ireland and Kan ha diskan from Brittany. Other traditional unaccompanied styles sung currently are Waulking song and Psalm singing or Lining out both from Scotland.[38]

The emergence of folk-rock led to the creation of a popular music genre labelled Celtic music which "frequently involves the blending of traditional and modern forms, e.g. the Celtic-punk of The Pogues, the ambient music of Enya ... the Celtic-rock of Runrig, Rawlins Cross and Horslips."[39] Pan-Celtic music festivals were established, notably the Festival Interceltique de Lorient founded in 1971, which has occurred annually since.

Festivals

Pipers at the

Festival Interceltique de LorientMain articles: List of Celtic festivals, Eisteddfod, Mod (Scotland), Fleadh Cheoil, Fleadh, and Fest NozThe Scottish Mod and Irish Fleadh Cheoil are seen as an equivalent to the Breton Fest Noz and Welsh Eisteddfod.[40][41][42]

The birthdays of the most important Celtic Saints of Celtic Christianity for each Celtic nation have become the focus for festivals, feasts and marches: Ireland - Saint Patrick's Day,[43] Wales - Saint David's Day,[44] Scotland - Saint Andrew's Day,[45] Cornwall - Saint Piran's Day,[46] Isle of Man - St Maughold's Feast Day [47] and Brittany - Grand Pardon of Sainte-Anne-d'Auray Pilgrimage.[48]

See also

References

- ^ "Celtic League - About us". http://www.celticleague.net/about-us/.

- ^ a b "Who were the Celts? ... Rhagor". Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales website. Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales. 2007-05-04. http://www.museumwales.ac.uk/en/rhagor/article/1939/. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ^ Chadwick, Nora (1970). The Celts. Penguin Books. pp. 53.

- ^ Wightman, Edith Mary (1985). Gallia Belgica. University of California Press. pp. 12, 26–29. ISBN 0-520-05297-8. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=aEyS54uSj88C&printsec=frontcover&dq=gallia+belgica#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Laurent, Peter Edmund (1868). An introduction to the study of ancient geography. Oxford. pp. 20, 21. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=Q00ZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA20&lpg=PA20&dq=Gallia+Aquitania#v=onepage&q=Gallia%20Aquitania&f=false.

- ^ Weber, Eugen (1991) "Gauls versus Franks: conflict and nationalism", in Nationhood and Nationalism in France, edited by Robert Tombs. London: HarperCollins Academic; Dietler, Michael (1994) "'Our ancestors the Gauls': archaeology, ethnic nationalism, and the manipulation of Celtic identity in modern Europe", American Anthropologist 96:584-605.

- ^ "A brief history of the Cornish language". Maga Kernow. http://www.magakernow.org.uk/index.aspx?articleid=38590#Revival.

- ^ Beresford Ellis, Peter (1990, 1998, 2005). The Story of the Cornish Language. Tor Mark Press. pp. 20–22. ISBN 0-85025-371-3.

- ^ The Guardian, editorial, 8 May 1990

- ^ "Things Celtic Music Directory : Festivals and Pubs". http://www.celticmp3s.com/things_celtic_music/Festivals_and_Pubs/. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "The Celtic League". Celtic League website. The Celtic League. 2010. http://www.celticleague.net/. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "Information on The International Celtic Congress Douglas, Isle of Man hosted by" (in Irish, English). Celtic Congress website. Celtic Congress. 2010. http://www.ccheilteach.ie/cc-hist-mellis.html. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "Visio-Map of Europe Celtic Europe.vsd" (PDF). http://www.breizh.net/icdbl/saozg/Celtic_Languages.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Celtic League American Branch - Celtic Nations". Celticleague.org. http://www.celticleague.org/celtic_nations.html. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "The Celts in Portugal" (PDF). http://www4.uwm.edu/celtic/ekeltoi/volumes/vol6/6_11/gamito_6_11.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- ^ "Oppida and Celtic society in western Spain" (PDF). http://www4.uwm.edu/celtic/ekeltoi/volumes/vol6/6_5/alvarez_sanchis_6_5.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Briga Toponyms in the Iberian Peninsula" (PDF). http://www4.uwm.edu/celtic/ekeltoi/volumes/vol6/6_15/garcia_alonso_6_15.pdf. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Galiza Celta". http://www.galizacelta.com/.

- ^ "The Old Celtic Dictionary". http://www.celticgrove.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=294:old-celtic-dictionary&catid=4:latest&Itemid=7.

- ^ "Old Celtic Dictionary". http://www.oldcelticdictionary.com/.

- ^ "Gallaic Revival Movement". http://gallaicrevivalmovement.ning.com/.

- ^ "Gallaic Revival Movement Home Page". http://www.gallaicrevivalmovement.spruz.com/.

- ^ Fischer, S. R. (2004) History of Language. Reaktion Books, p. 118

- ^ a b "Cumbric Revival". http://forum.stirpes.net/brythonic/24884-cumbric-revival.html.

- ^ "An Ger Dewnansek". http://members.fortunecity.com/gerdewnansek/.

- ^ "Cumbric Revival - Global". http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=91716548372&ref=search.

- ^ "The Gods of Gaul and the Continental Celts". pp. Chapter 3. http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/rac/rac06.htm#fr_61. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ^ Ministry of Canadian Heritage. Gaelic most common mother-tongue among Fathers of Confederation. URL accessed 26/04/2006.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2003, "Population characteristics: Ancestry of Australia's population" (from Australian Social Trends, 2003). Retrieved 1 September 2006.

- ^ Loffler, Marion A Book of Mad Celts: John Wickens and the Celtic Congress of Caernarfon 1904, Llandysul: Gomer Press, 2000, p. 38

- ^ Bempéchat, Paul-André, Allons enfants de quelle patrie? Breton nationalism and the Impressionist aesthetic, (Center for European Studies working papers).

- ^ http://www.pibydd.fsnet.co.uk/bagpipes.htm

- ^ http://www.ceolas.org/instruments/#bodhran

- ^ "The Australian Gaelic Singers at the Sydney A Capella Festival". http://www.sydneyacappellafestival.com.au/content.cfm/performers/The+Australian+Gaelic+Singers. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Alarik, Scott. "Irish Music and Scottish Music: What's the Difference, Really?". http://www.scottalarik.com/index.php?page=stories&family=&archives=show.

- ^ "Dan Y Cownter 3" (in Cymraeg, English). http://www.danycownter.com/. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ "Welsh Music Foundation" (in Cymraeg, English). http://www.welshmusicfoundation.com/. Retrieved 9 May 2010.

- ^ Robertson, Boyd & Taylor, Iain (1993) Gaelic: a complete course for beginners. London: Hodder & Stoughton; p. 53

- ^ Shuker, Roy (2005) Popular Music: the key concepts, Routledge; p. 38.

- ^ "Wales - Land of Song". 2008. http://www.analekta.com/media/analekta/analekta/file/1235402868_file.pdf. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ "Celtic Music". http://www.druidcircle.org/library/index.php?title=Celtic_Music. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ Robertson, Boyd and Taylor, Iain Gaelic - A Complete Course for Beginners; p. 63

- ^ "St Patrick's Day Parades and Events Worldwide". http://www.st-patricks-day.com/st_patricks_day_parades_home.asp.

- ^ "The National St David's Day Parade". http://www.stdavidsday.org/.

- ^ "St Andrew's Day: Scotland and around the world". http://www.scotland.org/standrewsday/.

- ^ "St Piran's Tide". http://www.an-daras.com/cutoms/cu_stpirans_events.htm.

- ^ "St Maughold's Feast Day". http://www.isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/parishes/md/stmaugh.htm.

- ^ "Grand Pardon de sainte Anne d'Auray". http://sainte-anne-auray.net/spip.php?article72.

Bibliography

- John Koch (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1851094407. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=f899xH_quaMC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Celtic+Culture:+A+Historical+Encyclopedia#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Alistair Moffat (2001). The Sea Kingdoms: The History of Celtic Britain and Ireland. HarperCollins. ISBN 0002572168. http://www.amazon.co.uk/Sea-Kingdoms-History-Britain-Ireland/dp/0002572168.

- Megaw, J. V. S & M. R. (1996). "Ancient Celts and modern ethnicity". Antiquity. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb3284/is_n267_v70/ai_n28668313/?tag=content;col1. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- Karl, Raimund (2004). Celtoscepticism. A convenient excuse for ignoring non-archaeological evidence?. http://books.google.com.au/books?id=3B0LFhbmkocC&pg=PR6&lpg=PR6&dq=Celtoscepticism.+A+convenient+excuse+for+ignoring+non-archaeological+evidence%3F#v=onepage&q=Celtoscepticism.%20A%20convenient%20excuse%20for%20ignoring%20non-archaeological%20evidence%3F&f=false. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- Ellis, P. B. (1992) "Introduction". Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford University Press

- Davies, Norman (1999) The Isles: a history. Oxford University Press

- Dietler, Michael (2006) " Celticism, Celtitude, and Celticity: the consumption of the past in the age of globalization". Celtes et Gaulois dans l’histoire, l’historiographie et l’idéologie moderne. Bibracte, Centre Archéologique Européen

- O'Driscoll, Robert (ed.) (1981) The Celtic Consciousness. George Braziller, Inc, New York City.

- Patrick Ryan, 'Celticity and storyteller identity: the use and misuse of ethnicity to develop a storyteller's sense of self', Folklore 2006.

External links

- Celtic Friends Network - Meet Modern Celts and top Celtic artists from around the world.

- Celtic League

- Galizan Celtic League

- Celtic League - American Branch

- The Celtic Realm

- CelticCountries.com - Monthly magazine on current affairs in the Celtic nations

- Celtic-World.Net, - Various information on Celtic culture and music

- National Geographic Map: The Celtic RealmPDF (306 KB)

- The Celtic Nations

- soc.culture.celtic newsgroup FAQ

- Music

- Dan Y Cownter 3 - Welsh Music Foundation artists (Cymraeg, English)

- Hoax Emcee - Hip Hop rapping (Cymraeg, English)

- James Graham - Puirt a beul (Gàidhlig)

- Julie Fowlis - BBC Radio 2 Folk Singer of the Year 2008 (Gàidhlig)

- Teine - Waulking song "Hi Rim Bo" (Gàidhlig)

- Christine Primrose - Traditional Scottish Gaelic songs (Gàidhlig)

- Puirt a beul in Ar Cànan 'S Ar Ceòl - Celtic Lyrics Corner (Gàidhlig, English)

- Puirt a beul in Cliar - Celtic Lyrics Corner (Gàidhlig, English)

- Kila Ireland (Gaeilge)

- Skwardya, Cornwall (Kernewek)

- Alan Stivell, Brittany - see "Tri Martalod" video link (Brezhoneg)

- Eluveitie Switzerland - Celtic Folk Metal (Gaulish)

Celts Ancient Celts

Celtic studiesPlacesGaelic Ireland · Dálriata / Alba · Iron Age Britain / Roman Britain / Sub-Roman Britain ·

Iron Age Gaul / Roman Gaul · Galatia · Gallaecia · Britonia · Balkans · TransylvaniaReligionSociety

Modern Celts

Celtic RevivalLanguages Proto-Celtic · Insular Celtic (Brythonic · Goidelic) · Continental Celtic (Celtiberian · Gaulish · Galatian · Gallaecian · Lepontic · Noric)Festivals Lists Celts · Tribes · Deities · English words of Celtic origin · Spanish words of Celtic origin · Galician words of Celtic origin · French words of Gaulish originCategories:- Celtic culture

- Cultural spheres of influence

- Ethnicity in politics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.