- Psycho (film)

-

Psycho

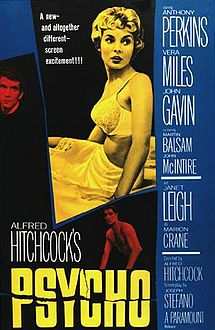

Theatrical release posterDirected by Alfred Hitchcock Produced by Alfred Hitchcock Screenplay by Joseph Stefano Based on Psycho by

Robert BlochStarring Anthony Perkins

Vera Miles

John Gavin

Martin Balsam

John McIntire

Janet LeighMusic by Bernard Herrmann Cinematography John L. Russell Editing by George Tomasini Studio Shamley Productions Distributed by Paramount Pictures (Original)

Universal PicturesRelease date(s) June 16, 1960 Running time 109 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $806,947 Box office $32,000,000 Psycho is a 1960 American suspense/psychological thriller film directed by Alfred Hitchcock and starring Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins. The film is based on the screenplay by Joseph Stefano, who adapted it from the 1959 novel of the same name by Robert Bloch. The novel was loosely inspired by the crimes of Wisconsin murderer and grave robber Ed Gein,[1] who lived just 40 miles from Bloch.

The film depicts the encounter between a secretary, Marion Crane (Leigh), hiding at a secluded motel after embezzling money from her employer, and the motel's disturbed owner and manager, Norman Bates (Perkins), and the aftermath of their encounter.[2]

Psycho initially received mixed reviews, but outstanding box office returns prompted a re-review which was overwhelmingly positive and led to four Academy Award nominations. Psycho is now considered one of Hitchcock's best films[3] and is highly praised as a work of cinematic art by international critics.[4] The film spawned two sequels, a prequel, a remake, and a television movie spin-off. In 1992, the film was selected to be preserved by the Library of Congress at the National Film Registry.

Contents

Plot

In need of money to marry her lover Sam Loomis (John Gavin), Phoenix secretary Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) steals $40,000 from one of her employer's clients and flees in her car. En route to Sam's California home, she parks along the road to sleep. A highway patrol officer awakens her and, suspicious of her agitated state, he begins to follow her. When she trades her car for another one at a car dealership, he notes the new vehicle's details. By the time Marion returns to the road, there is a heavy rainstorm which prompts her to spend the night at the Bates Motel rather than drive in the rain.

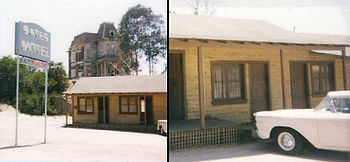

The "Psycho" set still stands on the Universal lot. At the time this picture was taken (1997), the car driven by Janet Leigh in the film was parked in front of the motel.

The "Psycho" set still stands on the Universal lot. At the time this picture was taken (1997), the car driven by Janet Leigh in the film was parked in front of the motel.

Owner Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) tells Marion he rarely has customers because of his location along an older, less-traveled highway, and mentions he lives with his mother in the house overlooking the motel. He then shyly invites Marion to have supper with him. She overhears Norman arguing with his mother about his supposed sexual interest in Marion, and during the meal, Marion angers him by suggesting he institutionalize his mother. He admits he would like to do so, but does not want to abandon her.

Marion resolves to return to Phoenix to return the money. As she undresses in her room, Norman watches through a peephole in his office wall. After calculating how she can repay the money she has spent, Marion flushes her notes down the toilet and begins to shower. Suddenly, an anonymous figure enters the bathroom and stabs Marion to death. Norman finds the corpse, and immediately assumes that his mother committed the murder. He cleans the bathroom and places Marion's body, wrapped in the shower curtain, and all her possessions—including the money—in the trunk of her car and sinks it in a nearby swamp.

Shortly afterward, Sam is contacted by both Marion's sister Lila (Vera Miles) and private detective Milton Arbogast (Martin Balsam), who has been hired by Marion's employer to find her and recover the money. Arbogast traces Marion to the motel and questions Norman, who lies unconvincingly about Marion having left weeks before. He refuses to let Arbogast talk to his mother, claiming she is ill. Arbogast calls Lila and tells her he will contact her again after hopefully questioning Norman's mother. Arbogast enters Norman's house and is attacked by a figure who slashes his face with a large kitchen knife, causing him to fall down the stairs, and then stabs him to death. Norman confronts his mother and urges her to hide in the cellar. She rejects the idea and orders him out of her room. Against her will, Norman carries her to the fruit cellar.

When Arbogast does not call Lila, she and Sam contact the local police. Deputy Sheriff Al Chambers is perplexed to learn Arbogast saw a woman in a window, revealing that Norman's mother had died ten years earlier. Norman had found her dead alongside her married lover; an apparent murder-suicide. When Chambers dismisses Lila and Sam's concerns over Arbogast's disappearance, the two decide to search the motel themselves. Posing as a married couple, Sam and Lila check into the motel and search Marion's cabin, where they find a scrap of paper with "$40,000" written on it. While Sam distracts Norman, Lila sneaks into the house to search for his mother. Sam suggests Norman killed Marion for the money so he could buy a new hotel. Realizing Lila is missing, Norman knocks Sam unconscious and rushes to the house. Lila sees him and hides in the cellar where she discovers the mummified body of Mrs. Bates. Seconds later, Norman rushes in, wearing his mother's clothes and a wig, and carrying a knife. Sam arrives just in time to subdue Bates and save Lila.

After Norman's arrest, forensic psychiatrist Dr. Fred Richmond (Simon Oakland) tells Sam and Lila that Mrs. Bates is alive in Norman's fractured psyche. After the death of Norman's father, the pair lived as if they were the only people in the world. When his mother found a lover, however, Norman was consumed with jealousy and murdered both of them. Wracked with guilt, he tried to "erase the crime" by bringing his mother "back to life" in his mind. He stole her corpse and preserved the body, and developed a split personality in which the two personas — Norman and "Mother" — coexist; when he is "Mother", he acts, talks and dresses as she would. Marion is revealed to have been "Mother"'s third victim, the first two also having been attractive young women; "Mother" is as jealous of Norman as he is of her, and so "she" kills anyone he feels attracted to. His psychosis protects him from knowing about other crimes committed after his mother's death.

Norman sits in a cell, his mind dominated by the Mother persona. In voiceover, she says that she will prove to the authorities that she is harmless by refusing to swat a fly on Norman's hand. Marion's car is shown being recovered from the swamp.

Cast

- Anthony Perkins as Norman Bates

- Janet Leigh as Marion Crane

- Vera Miles as Lila Crane

- John Gavin as Sam Loomis

- Martin Balsam as Det. Milton Arbogast

- John McIntire as Sheriff Al Chambers

- Simon Oakland as Dr. Fred Richmond

- Frank Albertson as Tom Cassidy

- Pat Hitchcock as Caroline

- Vaughn Taylor as George Lowery

- Lurene Tuttle as Mrs. Chambers

- John Anderson as California Charlie

- Mort Mills as Highway patrolman

- Virginia Gregg, Jeanette Nolan, and Paul Jasmin (all uncredited) as the voice of Norma Bates

- Ted Knight (uncredited) as a police officer

The success of Psycho jump-started Perkins's career, but he soon began to suffer from typecasting.[5] However, when Perkins was asked whether he would have still taken the role knowing that he would be typecast afterward, he replied with a definite "yes".[6]

Until her death, Leigh continued to receive strange and sometimes threatening calls, letters, and even tapes detailing what they would like to do to Marion Crane. One letter was so "grotesque" that she passed it along to the FBI, two of whose agents visited Leigh and told her the culprits had been located and that she should notify the FBI if she received any more letters of that type.[7]

Norman's mother was voiced by Paul Jasmin, Virginia Gregg, and Jeanette Nolan, who also provided some screams for Lila's discovery of the mother's corpse. The three voices were thoroughly mixed, except for the last speech, which is all Gregg's.[8]

Production

Development

Psycho is based on the 1959 novel of the same name by Robert Bloch which in turn is based loosely on the case of convicted Wisconsin murderer Ed Gein.[9] Both Gein and Psycho's protagonist, Norman Bates, were solitary murderers in isolated rural locations. Both had deceased domineering mothers, and had sealed off one room of their house as a shrine to their mother, and both dressed in women's clothing. However, there are many differences between Bates and Ed Gein. Among others, Gein would not be strictly considered a serial killer, having officially killed "only" two people.[10]

Peggy Robertson, Hitchcock's production assistant, read Anthony Boucher's positive review of the Bloch novel and decided to show the book to Hitchcock, even though readers at Hitchcock's home studio Paramount Pictures rejected its premise for a film. Hitchcock acquired rights to the novel for $9,500.[11] He reportedly ordered Robertson to buy up copies to keep the novel's surprises for the film.[12] Hitchcock chose to film Psycho to recover from two aborted projects with Paramount: Flamingo Feather and No Bail for the Judge. Hitchcock also faced genre competitors whose works were critically compared to his own and so wanted to film new material. The director also disliked stars' salary demands and trusted only a few people to choose prospective material, including Robertson.[13]

Paramount executives did not want to produce the film and refused to provide the budget that Hitchcock received from them for previous films with the studio.[14] Hitchcock decided to plan for Psycho to be filmed quickly and inexpensively, similar to an episode of his ongoing television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and hired the television series crew as Shamley Productions. He proposed this cost-conscious approach to Paramount but executives again refused to finance the film, telling him their sound stages were occupied or booked even though production was known to be in a slump. Hitchcock countered with the offer to finance the film personally and to film it at Universal-International if Paramount would distribute. He also deferred his director's fee of $250,000 for a 60% ownership of the film negative. This offer was finally accepted. Hitchcock also experienced resistance from producer Herbert Coleman and Shamley Productions executive Joan Harrison, who did not think the film would be a success.[15]

Novel adaptation

James Cavanaugh, who had written some of the Alfred Hitchcock Presents television shows, wrote the original screenplay.[16] Hitchcock rejected it, saying that the story dragged and read like a television short horror story.[17] His assistant recalls that the treatment was very dull.[16] Hitchcock reluctantly agreed to meet with Stefano, who had worked on only one film before. Despite Stefano's newness to the industry, the meeting went well, and Hitchcock hired him.[16]

The screenplay is relatively faithful to the novel, with a few notable adaptations by Hitchcock and Stefano. Stefano found the character of Norman Bates — who, in the book, is middle-aged, overweight, and more overtly unstable — unsympathetic, but became more intrigued when Hitchcock suggested the casting of Anthony Perkins.[17] Stefano eliminated Bates' drinking,[18] which evidently necessitated removing Bates' "becoming" the Mother personality when in a drunken stupor. Also gone is Bates' interest in spiritualism, the occult and pornography.[19] Hitchcock and Stefano elected to open the film with scenes in Marion's life, and not introduce Bates at all until 20 minutes into the film, rather than open with Bates reading a history book as Bloch does.[18] Indeed, writer Joseph W. Smith notes that, "Her story occupies only two of the novel's 17 chapters. Hitchcock and Stefano expanded this to nearly half the narrative".[20] He likewise notes there is no hotel tryst between Marion and Sam in the novel. For Stefano, the conversation between Marion and Norman in the hotel parlor in which she displays a maternal sympathy towards him makes it possible for the audience to switch their sympathies towards Norman Bates after Marion's murder.[21] When Lila Crane is looking through Norman's room, in the film she opens a book with a blank cover whose contents we do not see. In the novel these are "pathologically pornographic" illustrations. Stefano wanted to give the audience "indications that something was quite wrong, but it could not be spelled out or overdone."[21] In his book of interviews with Hitchcock, François Truffaut notes that the novel "cheats" by having extended conversations between Norman and "Mother" and stating what Mother is "doing" at various given moments.[22] For obvious reasons, these were omitted from the film.

The first name of the female protagonist was changed from Mary to Marion, since a real Mary Crane existed in Phoenix.[23] Also changed is the novel's budding romance between Sam and Lila. Hitchcock preferred to focus the audience's attention on the solution to the mystery rather than a budding romance,[24] and Stefano thought such a relationship would make Sam Loomis seem cheap.[21] Instead of having Sam explain Norman's pathology to Lila, the film simply has a psychiatrist do the talking.[25] (Stefano was in therapy dealing with his relationship with his own mother at the time of writing the film.)[26] The novel is more violent than the film; for instance, Crane is beheaded in the shower, as opposed to being stabbed to death.[16] Minor changes include changing Marion's telltale earring found after her death to a scrap of paper that failed to flush down the toilet. This provided some shock effect, since toilets were virtually never seen on screen in the 1960s.[27] The location of Arbogast's death was moved from the foyer to the stairwell. Stefano thought this would make it easier to conceal the truth about "Mother" without tipping that something was being hidden.[28] As Janet Leigh put it, this gave Hitchcock more options for his camera.[25]

Pre-production

Paramount, whose contract guaranteed another film by Hitchcock, did not want Hitchcock to make Psycho. Paramount was expecting No Bail for the Judge starring Audrey Hepburn, who became pregnant and had to bow out, leading Hitchcock to scrap the production. Their official stance was that the book was "too repulsive" and "impossible for films", and nothing but another of his star-studded mystery thrillers.[11][29] They did not like "anything about it at all" and denied him his usual budget.[11][29] So, Hitchcock financed the film's creation through his own Shamley Productions, shooting at Universal Studios under the Revue television unit.[14][30] Hitchcock's original Bates Motel and Psycho House movie set buildings, which were constructed on the same stage as Lon Chaney Sr.'s The Phantom of the Opera, are still standing at Universal Studios in Universal City near Hollywood and are a regular attraction on the studio's tour.[31][32] As a further result of cost cutting, Hitchcock chose to film Psycho in black and white, keeping the budget under $1,000,000.[33] Other reasons for shooting in black and white were his desire to prevent the shower scene from being too gory and his admiration for Les Diaboliques's use of black and white.[34][35]

To keep costs down and because he was most comfortable around them, Hitchcock took most of his crew from his television series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, including the cinematographer, set designer, script supervisor, and first assistant director.[36] He hired regular collaborators Bernard Herrmann as music composer, George Tomasini as editor, and Saul Bass for the title design and storyboarding of the shower scene. In all, his crew cost $62,000.[37]

Through the strength of his reputation, Hitchcock cast Leigh for a quarter of her usual fee, paying only $25,000 (in the 1967 book Hitchcock/Truffaut, Hitchcock said that Leigh owed Paramount one final film on her seven-year contract which she had signed in 1953).[38] His first choice, Leigh agreed after having only read the novel and making no inquiry into her salary.[23] Her co-star, Anthony Perkins, agreed to $40,000.[37] Both stars were experienced and proven box-office draws.

Paramount did distribute the film, but four years later Hitchcock sold his stock in Shamley to Universal's parent company and his next six films were made at and distributed by Universal.[30] After another four years, Paramount sold all rights to Universal.[30]

Filming

The film, independently produced by Hitchcock, was shot at Revue Studios,[39] the same location as his television show. Psycho was shot on a tight budget of $806,947.55,[40] beginning on November 11, 1959 and ending on February 1, 1960.[41][42] Filming started in the morning and finished by six or earlier on Thursdays (when Hitchcock and his wife would dine at Chasen's).[43] Nearly the whole film was shot with 50 mm lenses on 35 mm cameras. This trick closely mimicked normal human vision, which helped to further involve the audience.[44]

Before shooting began in November, Hitchcock dispatched assistant director Hilton Green to Phoenix to scout locations and shoot the opening scene. The shot was supposed to be an aerial shot of Phoenix that slowly zoomed into the hotel window of a passionate Marion and Sam. Ultimately, the helicopter footage proved too shaky and had to be spliced with footage from the studio.[45] Another crew filmed day and night footage on Highway 99 between Fresno and Bakersfield, California for projection when Marion drives from Phoenix. They also provided the location shots for the scene in which she is pulled over by the highway patrolman.[45] In one street scene shot in downtown Phoenix, Christmas decorations were discovered to be visible; rather than re-shoot the footage, Hitchcock chose to add a graphic to the opening scene marking the date as "Friday, December the Eleventh".[46]

Green also took photos of a prepared list of 140 locations for later reconstruction in the studio. These included many real estate offices and homes such as those belonging to Marion and her sister.[45] He also found a girl who looked just like he imagined Marion and photographed her whole wardrobe, which would enable Hitchcock to demand realistic looks from Helen Colvig, the wardrobe supervisor.[45] The look of the Bates Motel was modeled on Edward Hopper's painting The House by The Railroad.[47]

Both the leads, Perkins and Leigh, were given freedom to interpret their roles and improvise as long as it did not involve moving the camera.[48] An example of Perkins's improvisation is Norman's habit of munching on candy corn.[49]

Throughout filming, Hitchcock created and hid various versions of the "Mother corpse" prop in Leigh's dressing room closet. Leigh took the joke well, and she wondered whether it was done to keep her on edge and thus more in character or to judge which corpse would be scarier for the audience.[50]

During shooting, Hitchcock was forced to uncharacteristically do retakes for some scenes. The final shot in the shower scene, which starts with an extreme close-up on Marion's eye and pulls up and out, proved very difficult for Leigh, since the water splashing in her face made her want to blink, and the cameraman had trouble as well since he had to manually focus while moving the camera.[48] Retakes were also required for the opening scene, since Hitchcock felt that Leigh and Gavin were not passionate enough.[51] Leigh had trouble saying "Not inordinately" for the real estate office scene, requiring additional retakes.[52] Lastly, the scene in which the mother is discovered required complicated coordination of the chair turning around, Miles hitting the light bulb, and a lens flare, which proved to be the sticking point. Hitchcock forced retakes until all three elements were to his satisfaction.[53]

According to Hitchcock, a series of shots with Arbogast going up the stairs in the Bates house before he is stabbed were directed by Hilton Green, working with storyboard artist Saul Bass's drawings only while Hitchcock was incapacitated with the common cold. However, upon viewing the dailies of the shots, Hitchcock was forced to scrap them. He claimed they were "no good" because they did not portray "an innocent person but a sinister man who was going up those stairs".[54] Hitchcock later re-shot the scene, though a little of the cut footage made its way into the film. Filming the murder of Arbogast proved problematic owing to the overhead camera angle necessary to hide the film's twist. A camera track constructed on pulleys alongside the stairway together with a chairlike device had to be constructed and thoroughly tested over a period of weeks.[55]

Alfred Hitchcock's cameo is a signature occurrence in most of his films. In Psycho, he can be seen through a window, wearing a Stetson hat, standing outside Marion Crane's office.[56] Wardrobe mistress Rita Riggs says that Hitchcock chose this scene for his cameo so that he could be in a scene with his daughter (who played one of Marion's colleagues). Others have suggested that he chose this early appearance to avoid distracting the audience.[57]

Shower scene

The murder of Janet Leigh's character in the shower is the film's pivotal scene and one of the best known scenes in cinema history. As such, it spawned numerous myths and legends. It was shot from December 17 to December 23, 1959, and features 77 different camera angles.[58] The scene "runs 3 minutes and includes 50 cuts."[59] Most of the shots are extreme close-ups, except for medium shots in the shower directly before and directly after the murder. The combination of the close shots with their short duration makes the sequence feel more subjective than it would have been if the images were presented alone or in a wider angle, an example of the technique Hitchcock described as "transferring the menace from the screen into the mind of the audience".[60]

In order to capture the straight-on shot of the shower head, the camera had to be equipped with a long lens. The inner holes on the spout were blocked and the camera placed farther back, so that the water appears to be hitting the lens but actually went around and past it.[61]

The soundtrack of screeching violins, violas, and cellos was an original all-strings piece by composer Bernard Herrmann entitled "The Murder." Hitchcock originally wanted the sequence (and all motel scenes) to play without music,[62] but Herrmann begged him to try it with the cue he had composed. Afterward, Hitchcock agreed that it vastly intensified the scene, and he nearly doubled Herrmann's salary.[63][64][65] The blood in the scene is in fact chocolate syrup, which shows up better on black-and-white film, and has more realistic density than stage blood.[1] The sound of the knife entering flesh was created by plunging a knife into a melon.[66][67]

It is sometimes claimed that Leigh was not in the shower the entire time and that a body double was used. However, in an interview with Roger Ebert and in the book Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, Leigh stated that she was in the scene the entire time; Hitchcock used a live model as her stand-in only for the scenes in which Norman wraps up Marion's body in a shower curtain and places her body in the trunk of her car.[68] However, the 2010 book The Girl in Alfred Hitchcock's Shower by Robert Graysmith contradicts this, identifying Marli Renfro as Leigh's body double for some of the shower scenes.

Another popular myth is that in order for Leigh's scream in the shower to sound realistic, Hitchcock used ice-cold water. Leigh denied this on numerous occasions, saying that he was very generous with a supply of hot water.[69] All of the screams are Leigh's.[8]

Another myth was that Hitchcock told Leigh only to stand in the shower, and she had no idea that her character was actually going to be murdered, causing an authentic reaction. The most notorious urban legend arising from the production of Psycho began when Saul Bass, the graphic designer who created many of the title sequences of Hitchcock's films and storyboarded some of his scenes, claimed that he had actually directed the shower scene. This claim was refuted by several people associated with the film. Leigh, who is the focus of the scene, stated, "...absolutely not! I have emphatically said this in any interview I've ever given. I've said it to his face in front of other people... I was in that shower for seven days, and, believe me, Alfred Hitchcock was right next to his camera for every one of those seventy-odd shots."[70] Hilton Green, the assistant director and cameraman, also denies Bass's claim: "There is not a shot in that movie that I didn't roll the camera for. And I can tell you I never rolled the camera for Mr. Bass."[70] Roger Ebert, a longtime admirer of Hitchcock's work, was also amused by the rumor, stating, "It seems unlikely that a perfectionist with an ego like Hitchcock's would let someone else direct such a scene."[71]

However, commentators such as Stephen Rebello and Bill Krohn have established that Saul Bass did contribute to the creation of that scene in his capacity as a graphic artist.[72] Bass is credited for the design of the opening credits, and also as "Pictorial Consultant" in the credits. When interviewing Hitchcock, François Truffaut asked about the extent of Bass's contribution to the film, to which Hitchcock said that Bass designed the titles as well as provided storyboards for the Arbogast murder (which he claimed to have rejected), but made no mention of Bass providing storyboards for the shower scene.[73] According to Bill Krohn's Hitchcock At Work, Bass's first claim to have directed the scene was in 1970, when he provided a magazine with 48 drawings used as storyboards as proof.[74]

Krohn's analysis of the production of Psycho in his book Hitchcock at Work, while refuting Bass's claims for directing the scene, notes that these storyboards did introduce key aspects of the final scene—most notably, the fact that the killer appears as a silhouette, and details such as the shower curtain being torn down, the curtain rod being used as a barrier, and the transition from the hole of the drainage pipe to Marion Crane's dead eyes which (as Krohn notes) is highly reminiscent of the iris titles for Vertigo.[74]

Krohn's research also notes that Hitchcock shot the scene with two cameras: one a BNC Mitchell, the other a handheld camera called an Éclair which Orson Welles had used in Touch of Evil (1958). In order to create an ideal montage for the greatest emotional impact on the audience, Hitchcock shot a lot of footage of this scene which he trimmed down in the editing room. He even brought a Moviola on the set to gauge the footage required. The final sequence, which his editor George Tomasini worked on with Hitchcock's advice, went far beyond the basic paradigms set up by Bass's storyboards.[74]

According to Donald Spoto in The Dark Side of Genius, Hitchcock's wife, Alma Reville, spotted a blooper in one of the last screenings of Psycho before its official release: after Marion was supposedly dead, one could see her blink. According to Patricia Hitchcock, talking in Laurent Bouzereau's "making of" documentary, Alma spotted that Leigh's character appeared to take a breath. In either case, the postmortem activity was edited out and was never seen by audiences.[16] Although Marion's eyes should be dilated after her death, the contact lenses necessary for this effect would have required six weeks of acclimatization to wear them, so Hitchcock decided to forgo them.[75]

It is often claimed that, despite its graphic nature, the "shower scene" never once shows a knife puncturing flesh.[76][77][78] However, a frame by frame analysis of the sequence shows one shot in which the knife apparently penetrates Leigh's abdomen (actually a prosthetic prop) but it is acknowledged this could be created by lighting and reverse motion.[79] Leigh herself was so affected by this scene when she saw it, that she no longer took showers unless she absolutely had to; she would lock all the doors and windows and would leave the bathroom and shower door open.[80] She never realized until she first watched the film "how vulnerable and defenseless one is".[16]

Leigh and Hitchcock fully discussed what the scene meant:

Marion had decided to go back to Phoenix, come clean, and take the consequence, so when she stepped into the bathtub it was as if she were stepping into the baptismal waters. The spray beating down on her was purifying the corruption from her mind, purging the evil from her soul. She was like a virgin again, tranquil, at peace.[70]Film theorist Robin Wood also discusses how the shower washes "away her guilt". He comments upon the "alienation effect" of killing off the "apparent center of the film" with which spectators had identified.[81]

Soundtrack

Score

Hitchcock insisted that Bernard Herrmann write the score for Psycho, in spite of the composer's refusal to accept a reduced fee for the film's lower budget.[82] The resulting score, according to Christopher Palmer in The Composer in Hollywood (1990) is "perhaps Herrmann's most spectacular Hitchcock achievement."[83] Hitchcock was pleased with the tension and drama the score added to the film,[84] later remarking "33% of the effect of Psycho was due to the music."[85] The singular contribution of Herrmann's score may be inferred from the film's credit roll, where the composer's name precedes only the director's own, a distinction unprecedented in the annals of commercial cinematic music. Herrmann used the lowered music budget to his advantage by writing for a string orchestra rather than a full symphonic ensemble,[82] disregarding Hitchcock's request for a jazz score.[86] He thought of the single tone color of the all-string soundtrack as a way of reflecting the black-and-white cinematography of the film.[87] Hollywood composer Fred Steiner, in an analysis of the score to Psycho, points out that string instruments gave Herrmann access to a wider range in tone, dynamics and instrumental special effects than any other single instrumental group would have.[88]

The main title music, a tense, contrapuntal piece, sets the tone of impending violence, and returns three times on the soundtrack.[89][90] Though nothing shocking occurs during the first 15–20 minutes of the film, the title music remains in the audience's mind, lending tension to these early scenes.[89] Herrmann also maintains tension through the slower moments in the film through the use of ostinato.[85]

There were rumors that Herrmann had used electronic means, including amplified bird screeches to achieve the shocking effect of the music in the Shower Scene. The effect was achieved, however, only with violins in a "screeching, stabbing sound-motion of extraordinary viciousness."[91] The only electronic amplification employed was in the placing of the microphones close to the instruments, to get a harsher sound.[91] Besides the emotional impact, the Shower Scene cue ties the soundtrack to birds.[91] The association of the Shower Scene music with birds also telegraphs to the audience that it is Norman, the stuffed-bird collector, who is the murderer rather than his mother.[91]

Herrmann biographer Steven C. Smith writes that the music for the Shower Scene is "probably the most famous (and most imitated) cue in film music,"[87] but Hitchock was originally opposed to having music in this scene.[91] When Herrmann played the Shower Scene cue for Hitchcock, the director approved its use in the film. Herrmann reminded Hitchcock of his instructions not to score this scene, to which Hitchcock replied, "Improper suggestion, my boy, improper suggestion."[92] This was one of two important disagreements Hitchcock had with Herrmann, in which Herrmann ignored Hitchcock's instructions. The second one, over the score for Torn Curtain (1966), resulted in the end of their professional collaboration.[93] A survey conducted by PRS for Music, in 2009, showed that the British public consider the score from 'the shower scene' to be the scariest theme from any film.[94]

To honor the 50th anniversary of Psycho, in July 2010, the San Francisco Symphony[95] obtained a print of the film with the soundtrack removed, and projected it on a large screen in Davies Symphony Hall while the orchestra performed the score live. This was previously mounted by the Seattle Symphony in October, 2009 as well, performing at the Benroya Hall for two consecutive evenings.

Recordings

Several CDs of the film soundtrack have been released, including:

- The 1970s soundtrack recording with Bernard Herrmann conducting the National Philharmonic Orchestra [Unicorn CD, 1993].[96]

- The 1997 Varèse Sarabande CD features all the music scored in the film, but the pieces were re-recorded in 1975 by the composer.[96]

- The 1998 Soundstage Records SCD 585 CD claims to feature the tracks from the original master tapes. However, it has been asserted that the release is a bootleg recording.[96]

- Track listing (Psycho — Soundstage Records)

- All pieces by Bernard Herrmann.

- "Prelude; The City; Marion and Sam; Temptation" - 6:15

- "Flight; The Patrol Car; The Car Lot; The Package; The Rainstorm" - 7:21

- "Hotel Room; The Window; The Parlour; The Madhouse; The Peephole" - 8:52

- "The Bathroom; The Murder; The Body; The Office; The Curtain; The Water; The Car; The Swamp" - 6:58

- "The Search; The Shadow; Phone Booth; The Porch; The Stairs; The Knife" - 5:41

- "The Search; The First Floor; Cabin 10; Cabin 1" - 6:18

- "The Hill; The Bedroom; The Toys; The Cellar; Discovery; Finale" - 5:00

Controversy

Psycho is a prime example of the type of film that appeared in the United States during the 1960s after the erosion of the Production Code. It was unprecedented in its depiction of sexuality and violence, right from the opening scene in which Sam and Marion are shown as lovers sharing the same bed, with Marion in a bra.[97] In the Production Code standards of that time, unmarried couples shown in the same bed would be taboo.[98]

According to the book Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, the censors in charge of enforcing the Production Code wrangled with Hitchcock because some of them insisted they could see one of Leigh's breasts. Hitchcock held onto the print for several days, left it untouched, and resubmitted it for approval. Each of the censors reversed their positions: those who had previously seen the breast now did not, and those who had not, now did. They passed the film after the director removed one shot that showed the buttocks of Leigh's stand-in.[99] The board was also upset by the racy opening, so Hitchcock said that if they let him keep the shower scene he would re-shoot the opening with them on the set. Since they did not show up for the re-shoot, the opening stayed.[99]

Another cause of concern for the censors[100][101][102] was that Marion was shown flushing a toilet, with its contents (torn-up note paper) fully visible. Up until that time in mainstream film and television in the U.S., a toilet flushing was never heard, let alone seen. A possible exception is the Turner Classic Movies print of the 1959 Walt Disney film The Shaggy Dog, in which a toilet is heard flushing off-camera. However, because of the possibility of audio dubbing in restorations and reissues of the film over the years, today it is unclear whether or not the sound of the toilet flushing was in the original 1959 release.

Also, according to the "Making of" featurette on the Collector's Edition DVD, some censors objected to the use of the word "transvestite" in the film's closing scenes.[16] This objection was withdrawn after writer Joseph Stefano took out a dictionary and proved to them that the word carried no hidden sexual context, but merely referred to "a man who likes to wear womens clothing".[102]

Internationally, Hitchcock was forced to make minor changes to the film, mostly to the shower scene. In Britain the shot of Norman washing blood from his hands was objected to and in Singapore, though the shower scene was left untouched, the murder of Arbogast and a shot of Mother's corpse were removed.[103]

Promotion

Hitchcock did most of the promotion on his own, forbidding Leigh and Perkins to make the usual television, radio, and print interviews for fear of their revealing the plot.[104] Even critics were not given private screenings but rather had to see the film with the general public, which, despite possibly affecting their reviews,[103] certainly preserved the plot.

The film's original trailer features a jovial Hitchcock taking the viewer on a tour of the set, and almost giving away plot details before stopping himself. It is "tracked" with Bernard Herrmann's Psycho theme, but also jovial music from Hitchcock's comedy The Trouble with Harry; most of Hitchcock's dialogue is post-synchronized. The trailer was made after completion of the film, and since Janet Leigh was no longer available for filming, Hitchcock had Vera Miles don a blonde wig and scream loudly as he pulled the shower curtain back in the bathroom sequence of the preview. Since the title, "Psycho," instantly covers most of the screen, the switch went unnoticed by audiences for years. However a freeze-frame analysis clearly reveals that it is Vera Miles and not Janet Leigh in the shower during the trailer.[30]

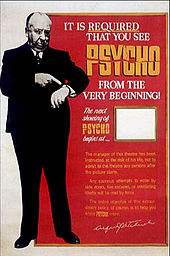

The most controversial move was Hitchcock's "no late admission" policy for the film, which was unusual for the time. It was not entirely original as Clouzot had done the same in France for Les Diaboliques.[105] Hitchcock thought that if people entered the theater late and never saw the star actress Janet Leigh, they would feel cheated.[30] At first theater owners opposed the idea, claiming that they would lose business. However, after the first day, the owners enjoyed long lines of people waiting to see the film.[30]

The film was so successful that it was reissued to theaters in 1965. A year later, CBS purchased the television rights for $450,000. CBS planned to televise the film on September 23, 1966, but three days earlier, Valerie Percy, daughter of Illinois senate candidate Charles H. Percy, was murdered. As her parents slept mere feet away, she was stabbed a dozen times with a double-edged knife. In light of the murder, CBS agreed to postpone the screening, but as a result of the Apollo pad fire of January 27, 1967, the network washed its hands of Psycho,[106] and shortly afterward Paramount included the film in its first syndicated package of post-1950 movies, "Portfolio I." WABC-TV in New York City was the first station in the country to air Psycho (with some scenes significantly edited), on its late-night movie series, The Best of Broadway, on June 24, 1967.[107] Following another successful theatrical reissue in 1969, the film finally made its way to general television airing in one of Universal's syndicated programming packages for local stations in 1970. Psycho was aired for twenty years in this format, then leased to cable for two years before returning to syndication as part of the "List of a Lifetime" package.[106]

Interpretations

Subversion of romance through irony

In Psycho, Hitchcock subverts the romantic elements that are seen in most of his work. The film is instead ironic as it prevents "clarity and fulfillment" of romance. The past is central to the film; the main characters "struggle to understand and resolve destructive personal histories" and ultimately fail.[108] Lesley Brill writes, "The inexorable forces of past sins and mistakes crush hopes for regeneration and present happiness." The crushed hope is highlighted by the death of the protagonist, Marion Crane, halfway through the film.[109] Marion is like Persephone of Greek mythology, who is abducted temporarily from the world of living. The myth does not sustain with Marion, who dies hopelessly in her room at the Bates Motel. The room is wallpapered with floral print like Persephone's flowers, but they are only "reflected in mirrors, as images of images—twice removed from reality". In the scene of Marion's death, Brill describes the transition from the bathroom drain to Marion's lifeless eye, "Like the eye of the amorphous sea creature at the end of Fellini's La Dolce Vita, it marks the birth of death, an emblem of final hopelessness and corruption." Unlike heroines in Hitchcock's other films, she does not reestablish her innocence or discover love.[110]

Marion is deprived of "the humble treasures of love, marriage, home and family", which Hitchcock considers elements of human happiness. There exists among Psycho's secondary characters a lack of "familial warmth and stability", which demonstrates the unlikelihood of domestic fantasies. The film contains ironic jokes about domesticity, such as when Sam writes a letter to Marion, agreeing to marry her, only after the audience sees her buried in the swamp. Sam and Marion's sister Lila, in investigating Marion's disappearance, develop an "increasingly connubial" relationship, a development that Marion is denied.[111] Norman also suffers a similarly perverse definition of domesticity. He has "an infantile and divided personality" and lives in a mansion whose past occupies the present. Norman displays stuffed birds that are "frozen in time" and keeps childhood toys and stuffed animals in his room. He is hostile toward suggestions to move from the past, such as with Marion's suggestion to put his mother "someplace" and as a result kills Marion to preserve his past. Brill explains, "'Someplace' for Norman is where his delusions of love, home, and family are declared invalid and exposed."[112]

Light and darkness feature prominently in Psycho. The first shot after the intertitle is the sunny landscape of Phoenix before the camera enters a dark hotel room where Sam and Marion appear as bright figures. Marion is almost immediately cast in darkness; she is preceded by her shadow as she reenters the office to steal money and as she enters her bedroom. When she flees Phoenix, darkness descends on her drive. The following sunny morning is punctured by a watchful police officer with black sunglasses, and she finally arrives at the Bates Motel in near darkness.[113] Bright lights are also "the ironic equivalent of darkness" in the film, blinding instead of illuminating. Examples of brightness include the opening window shades in Sam's and Marion's hotel room, vehicle headlights at night, the neon sign at the Bates Motel, "the glaring white" of the bathroom tiles where Marion dies, and the fruit cellar's exposed light bulb shining on the corpse of Norman's mother. Such bright lights typically characterize danger and violence in Hitchcock's films.[114]

Motifs

The film often features shadows, mirrors, windows, and, less so, water. The shadows are present from the very first scene where the blinds make bars on Marion and Sam as they peer out the window. The stuffed birds' shadows loom over Marion as she eats, and Norman's mother is seen in only shadows until the very end. More subtly, back-lighting turns the rakes in the hardware store into talons above Lila's head.[115]

Mirrors reflect Marion as she packs, her eyes as she checks the rear-view mirror, her face in the policeman's sunglasses, and her hands as she counts out the money in the car dealership's bathroom. A motel window serves as a mirror by reflecting Marion and Norman together. Hitchcock shoots through Marion's windshield and the telephone booth, when Arbogast phones Sam and Lila. The heavy downpour can be seen as foreshadowing of the shower, and it letting up can be seen as a symbol of Marion making up her mind to return to Phoenix.[115]

There are a number of references to birds. Marion's last name is Crane and she is from Phoenix. Norman's hobby is stuffing birds, and he comments that Marion eats like a bird. Marion's first car was a Thunderbird.[115] The motel room has pictures of birds on the wall. When Norman accidentally knocks one off, he's identified as the killer—he has, in British slang, "offed a bird" (killed a young woman).

Psychoanalytic interpretation

Psycho has been called "the first psychoanalytical thriller."[116] The sex and violence in the film were unlike anything previously seen in a mainstream film. "[T]he shower scene is both feared and desired," wrote French film critic Serge Kaganski. "Hitchcock may be scaring his female viewers out of their wits, but he is turning his male viewers into potential rapists, since Janet Leigh has been turning men on ever since she appeared in her brassiere in the first scene."[116]

In his documentary The Pervert's Guide to Cinema, Slavoj Žižek remarks that Norman Bates's mansion has three floors, paralleling the three levels of the human mind that are postulated by Freudian psychoanalysis: the top floor would be the superego, where Bates's mother lives; the ground floor is then Bates's ego, where he functions as an apparently normal human being; and finally, the basement would be Bates's id. Žižek interprets Bates's moving his mother's corpse from top floor to basement as a symbol for the deep connection that psychoanalysis posits between superego and id.[117]

Reception

Initial reviews of the film were thoroughly mixed.[118] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote, "There is not an abundance of subtlety or the lately familiar Hitchcock bent toward significant and colorful scenery in this obviously low-budget job." Crowther called the "slow buildups to sudden shocks" reliably melodramatic but contested Hitchcock's psychological points, reminiscent of Krafft-Ebing's studies, as less effective. While the film did not conclude satisfactorily for the critic, he commended the cast's performances as "fair".[119] British critic C. A. Lejeune was so offended that she not only walked out before the end but permanently resigned her post as film critic for The Observer.[120] Other negative reviews stated, "a blot on an honorable career", "plainly a gimmick movie", and "merely one of those television shows padded out to two hours."[118][121] Positive reviews stated, "Anthony Perkins' performance is the best of his career... Janet Leigh has never been better", "played out beautifully", and "first American movie since Touch of Evil to stand in the same creative rank as the great European films."[118][122] A good example of the mix is the New York Herald Tribune's review, which stated, "...rather difficult to be amused at the forms insanity may take... keeps your attention like a snake-charmer."[118]

The public loved the film, with lines stretching outside of theatres as people had to wait for the next showing. It broke box-office records in Japan, China and the rest of Asia, France, Britain, South America, the United States and Canada, and was a moderate success in Australia for a brief period.[118] It is one of the largest-grossing black-and-white films and helped make Hitchcock a multimillionaire and the third-largest shareholder in Universal.[123] Psycho was, by a large margin, the top moneymaking film of Hitchcock's career, earning $11,200,000 ($82.5 million in 2010, adjusted for inflation).[124]

In the United Kingdom, the film shattered attendance records at the London Plaza Cinema, but nearly all British critics panned it, questioning Hitchcock's taste and judgment. Reasons cited for this were the critics' late screenings, forcing them to rush their reviews, their dislike of the gimmicky promotion, and Hitchcock's expatriate status.[125] Perhaps thanks to the public's response and Hitchcock's efforts at promoting it, the critics did a re-review, and the film was praised. Time magazine switched its opinion from "Hitchcock bears down too heavily in this one" to "superlative" and "masterly", and Bosley Crowther put it on his Top Ten list of 1960.[125]

Psycho was initially criticized for making other filmmakers more willing to show gore; three years later, Blood Feast, considered to be the first "gore film", was released.[126] Psycho's success financially and critically had others trying to ride its coattails. Inspired by Psycho, Hammer Film Productions launched a series of mystery thrillers including The Nanny[127] (1965) starring Bette Davis and William Castle's Homicidal (1961) was followed by a whole slew of more than 13 other splatter films.[126]

Recognition

Award Category Name Outcome Academy Awards (33rd) Director Alfred Hitchcock Nominated Best Supporting Actress Janet Leigh Nominated Best Cinematography, Black-and White John L. Russell Nominated Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Black-and-White Joseph Hurley, Robert Clatworthy, George Milo Nominated Directors Guild of America Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures Alfred Hitchcock Nominated Edgar Allan Poe Awards Best Motion Picture Joseph Stefano (screenwriter), Robert Bloch (author) Won International Board of Motion Picture Reviewers Best Actor Anthony Perkins Tied Golden Globe Awards (18th) Best Supporting Actress Janet Leigh Won Writers Guild of America, East Best Written American Drama Joseph Stefano Nominated In 1992, the film was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Leigh asserted, "no other murder mystery in the history of the movies has inspired such merchandising."[128] Any number of items emblazoned with Bates Motel, stills, lobby cards, and highly valuable posters are available for purchase. In 1992, it was adapted scene-for-scene into three comic books by the Innovative Corporation.[128]

Psycho has appeared on a number of lists by websites, television channels, and magazines. The shower scene was featured as number four on the list of Bravo Network's 100 Scariest Movie Moments,[129] whilst the finale was ranked number four on Premiere's similar list.[130] Entertainment Weekly's book titled The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time ranked the film as #11.[1]

Recognition by American Film Institute Recognition Year Ranking Notes AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies 1998 #18 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Thrills 2001 #1 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains 2003 #2 Norman Bates (Villain) AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes 2005 #56 "A boy's best friend is his mother." AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores 2005 #4 AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies 2007 #14 The line, "We all go a little mad sometimes." was also nominated for AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes.

Sequels and remakes

Three sequels were produced: Psycho II (1983), Psycho III (1986), and Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990), the last being a part-prequel television movie written by the original screenplay author, Joseph Stefano. Anthony Perkins returned to his role of Norman Bates in all three sequels, and also directed the third film. The voice of Norman Bates's mother was maintained by noted radio actress Virginia Gregg with the exception of Psycho IV, where the role was played by Olivia Hussey. Vera Miles also reprised her role of Lila Crane in Psycho II.[131] The sequels were well received but considered inferior to the original.[132][133]

Bates Motel was a failed television pilot spin-off which later aired as a television movie (before the release of Psycho IV). Anthony Perkins declined to appear in the pilot, so Norman's cameo appearance was played by Kurt Paul, who was Perkins's stunt double on Psycho II and III.[134] In 1998, Gus Van Sant directed a remake of Psycho. The film is in color and features a different cast, but aside from this it is a virtually shot-for-shot remake copying Hitchcock's camera movements and editing.[135] A Conversation with Norman (2005), directed by Jonathan M. Parisen, was a film inspired by Psycho.

As of 2010, a drama film is in development based on the book by Stephen Rebello, Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho. The film will be entitled Alfred Hitchcock Presents and will be directed by Ryan Murphy and star Anthony Hopkins as Hitchcock.[136]

Cultural impact

Psycho has become one of the most recognizable films in cinema history, and is arguably Hitchcock's best known film.[137][138] In his novel, Bloch used an uncommon plot structure: he repeatedly introduced sympathetic protagonists, then killed them off. This played on his reader's expectations of traditional plots, leaving them uncertain and anxious. Hitchcock recognized the effect this approach could have on audiences, and utilized it in his adaptation, killing off Leigh's character at the end of the first act. This daring plot device, coupled with the fact that the character was played by the biggest box-office name in the film, was a shocking turn of events in 1960.[97]

The most original and influential moment in the film is the "shower scene", which became iconic in pop culture because it is often regarded as one of the most terrifying scenes ever filmed. Part of its effectiveness was due to the use of startling editing techniques borrowed from the Soviet montage filmmakers,[139][140] and to the iconic screeching violins in Bernard Herrmann's musical score. The iconic shower scene is frequently spoofed, given homage to and referenced in popular culture, complete with the violin screeching sound effects (see Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, among many others).[141]

Psycho is now widely considered to be the first film in the slasher film genre,[142][143] and has been referenced in films numerous times; examples include the 1974 musical horror film Phantom of the Paradise, 1978 horror film Halloween (which starred Jamie Lee Curtis, Janet Leigh's daughter),[144] the 1977 High Anxiety, the 1980 Fade to Black, the 1980 Dressed to Kill and Wes Craven's 1996 horror satire Scream.[145] Bernard Herrmann's opening theme has been sampled by rapper Busta Rhymes on his song "Gimme Some More".[146] In the comic book stories of Jonni Future, the house inherited by title character is patterned after the Bates Hotel.[147] The ending sequence is also parodied by South Park in Season 15, Episode 6 "City Sushi."

Ratings

Psycho has been rated and re-rated several times over the years by the MPAA. Upon its initial release, the film received a certificate stating that it was "Approved" (certificate #19564) under the simple pass/fail system of the Production Code in use at that time. Later, when the MPAA switched to a voluntary letter ratings system in 1968, Psycho was one of a number of high-profile motion pictures to be retro-rated with an "M" (Mature Audiences).[148] This remained the only rating the film would receive for 16 years, and according to the guidelines of the time "M" was the equivalent of a "PG" rating.[149] Then, in 1984, during the uproar of increased parental concern regarding violence in "PG" films,[149] Psycho was retro-rated again to its current rating of "R." This rating took effect, however, before the institution of the "PG-13" rating by the MPAA that same year, and there are those who have speculated that if the rating had existed at the time, or if Psycho were rated in America today, it would receive a "PG-13."

Home media

The film has been released several times on videotape, LaserDisc, and DVD. MCA DiscoVision Incorporated (parent company, MCA Inc) first released Psycho on the LaserDisc format in "standard play" (5 sides) in 1979, and "extended play" (2 sides) in October 1981. MCA/Universal Home Video released a new LaserDisc version of Psycho in August 1988 (Catalog #: 11003). In May 1998, Universal Studios Home Video released a deluxe edition of Psycho as part of their Signature Collection. This THX® certified Widescreen (1.85:1) LaserDisc Deluxe Edition (Catalog #: 43105) is spread across 4 extended play sides and 1 standard play side, and includes a new documentary and isolated Bernard Hermann score. A DVD edition was released in at the same time as the LaserDisc.[150]

Laurent Bouzereau produced a documentary looking at the film's production and reception for the initial DVD release. Universal released a 50th Anniversary edition on Blu-ray in the United Kingdom on 9 August 2010,[151] with Australia following with the same edition (featuring a different cover) being made available on the 1st of September 2010.

[152] A Blu-ray in US was released on October 19, 2010 to mark the film's 50th anniversary, featuring yet another different cover.[153]

References

- ^ a b c The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time. New York: Entertainment Weekly Books, 1999

- ^ Motion Picture Purgatory: Psycho

- ^ Psycho is the top listed Hitchcock film in The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time by Entertainment Weekly, and the highest Hitchcock film on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies.

- ^ "Psycho reviews". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/psycho/. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ Leigh, pp. 156, 187–188, 163

- ^ Leigh, p. 159

- ^ Leigh, pp. 132–133

- ^ a b Leigh, p. 83

- ^ Rebello 1990, pp. 7–14

- ^ Reavill, Gil (2007). Aftermath, Inc.: Cleaning Up After CSI Goes Home. Gotham. p. 228. ISBN 9781592402960. "With only two confirmed kills, Ed did not technically qualify as a serial killer (the traditional minimum requirement was three)"

- ^ a b c Leigh, p. 6

- ^ Rebello 1990, pp. 19–20

- ^ Rebello 1990, pp. 18–19

- ^ a b Rebello 1990, p. 23

- ^ Rebello 1990, pp. 26–29

- ^ a b c d e f g The Making of Psycho, 1997 documentary directed by Laurent Bouzereau, Universal Studios Home Video, available on selected Psycho DVD releases.

- ^ a b Leigh, pp. 36–37

- ^ a b Rebello 1990, p. 39

- ^ Tangentially mentioned by interviewer of Stefano [1] but generally given less attention than the film's omission of Bates's alcoholism and pornography.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 15

- ^ a b c Interview in Creative ScreenWriting Journal. Reproduced at

- ^ Truffaut 1967, p. 268

- ^ a b Leigh, pp. 33–34

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 16

- ^ a b Leigh, p. 39

- ^ Caminer & Gallagher 1996

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 47

- ^ Interview with Stefano

- ^ a b Rebello 1990, p. 13

- ^ a b c d e f Leigh, pp. 96–97

- ^ Leigh, pp. 86, 173

- ^ See WikiMapia {Coordinates: 34°8'12"N 118°20'48"W}.

- ^ Rothenberg, Robert S. (July 2001). "Getting Hitched — Alfred Hitchcock films released on digital video disks.". USA Today (Society for the Advancement of Education).. http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1272/is_2674_130/ai_76550723. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 82

- ^ CBS/AP (May 20, 2004). "'Psycho' Voted Best Movie Death: British Film Magazine Rates It Ahead Of 'Strangelove,' 'King Kong'". CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2004/05/20/entertainment/main618647.shtml. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 28

- ^ a b Leigh, pp. 12–13

- ^ Truffaut 1967

- ^ Hall, John W. (September 1995). "Touch of Psycho? Hitchcock, Welles.". Bright Lights Film Journal. http://www.brightlightsfilm.com/14/psycho.html. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Leigh, pp. 22–23

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 128

- ^ Leigh, p. 88

- ^ Leigh, p. 66

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 93

- ^ a b c d Leigh, pp. 24–26

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 90

- ^ Wagstaff 2004, p. 234 See also Liner notes to CD recording of score by Joel McNeely & Royal Scottish National Orchestra

- ^ a b Leigh, p. 73

- ^ Leigh, p. 62

- ^ Leigh, pp. 46–47

- ^ Leigh, p. 55

- ^ Leigh, p. 59

- ^ Leigh, pp. 87–88

- ^ Truffaut 1967, p. 273

- ^ Leigh, pp. 85–86

- ^ Allen 2007, p. 21

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 97

- ^ Leigh, pp. 65, 67

- ^ Dancyger 2002[page needed]

- ^ Hitchcock in an interview with Richard Schickel.Schickel, Richard; Frank Capra (2001). The Men Who Made the Movies. I.R. Dee. p. 308. ISBN 1566633745, 9781566633741.

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 144

- ^ "Mr. Hitchcock's suggestions for placement of music (08/Jan/1960)". January 1960. http://www.hitchcockwiki.com/wiki/Mr._Hitchcock%27s_suggestions_for_placement_of_music_%2808/Jan/1960%29. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ Leigh, pp. 165–166

- ^ Aspinall, David (September 2003). "Bernard Herrmann: Psycho: National Philharmonic, conducted by composer.". The Film Music Pantheon #3. Audiophilia.. http://www.audiophilia.com/features/da69.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Kiderra, Inga (Winter 2000). "Scoring Points". USC Trojan Family Magazine.. http://www.usc.edu/dept/pubrel/trojan_family/winter00/FilmScoring/Music_pg1.html. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Lehmann-Haupt, Christopher (May 7, 1990). "Books of The Times; 'Casaba,' He Intoned, and a Nightmare Was Born". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE0DE173CF934A35756C0A966958260&sec=&pagewanted=print. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ "Psycho stabbing 'best film death". BBC News. 20 May 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/3732949.stm. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (October 5, 2004). "Janet Leigh dies at age 77". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20041005/PEOPLE/41004009/1023. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Leitch, Luke (October 4, 2004). "Janet Leigh, star of Psycho shower scene, dies at 77". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 2007-12-05. http://web.archive.org/web/20071205234941/http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4153/is_20041004/ai_n12103901. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ a b c Leigh, pp. 67–70

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 15, 1996). "Movie Answer Man". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19961215/ANSWERMAN/612150303/1023. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 117

- ^ "Psycho: The Title Credits". http://notcoming.com/saulbass/caps_psycho.php. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ a b c Krohn 2003[page needed]

- ^ Leigh, pp. 176, 42

- ^ Leigh, p. 169

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1998-12-06). "Psycho (1960)". Great Movies (rogerebert.com). http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19981206/REVIEWS08/401010353/1023. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (2004-10-05). "Janet Leigh, 77, Shower Taker of 'Psycho,' Is Dead". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/05/movies/05leigh.html?ex=1254715200&en=596717cddaea56ef&ei=5090. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ^ "8 frames of "Psycho"". hitchcockwiki.com. 8 May 2008. http://www.hitchcockwiki.com/blog/?p=274. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Leigh, p. 131

- ^ Wood 1989, p. 146

- ^ a b Smith 1991, p. 236

- ^ Palmer 1990, pp. 273–274

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 240

- ^ a b Smith 1991, p. 241

- ^ Psycho – Bernard Herrmann. Soundtrack-express.com. Retrieved on 2010-11-21.

- ^ a b Smith 1991, p. 237

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 274

- ^ a b Palmer 1990, p. 275

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 238

- ^ a b c d e Palmer 1990, p. 277

- ^ Palmer 1990, p. 240

- ^ Smith 1991, p. 192

- ^ "Psycho shower music voted scariest movie theme tune". The Daily Telegraph (London). 2009-10-28. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/film-news/6456025/Psycho-shower-music-voted-scariest-movie-theme-tune.html. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "CSO - Friday Night at the Movies". Chicago. 2010-11-19. http://cso.org/TicketsAndEvents/EventDetails.aspx?eid=3530. Retrieved 2011-11-23.

- ^ a b c Bernard Herrmann and 50th anniversary of PSYCHO. Americanmusicpreservation.com (1960-06-16). Retrieved on 2010-11-21.

- ^ a b Psycho (1960). Retrieved November 20, 2010.

- ^ "Psycho – Classic Hitchcock Horror Turns 50". http://www.voxy.co.nz/entertainment/psycho-%E2%80%93-classic-hitchcock-horror-turns-50/1117/51910. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ a b Leigh, p. 112

- ^ "'Psycho' and deadly sin". http://cinepad.com/plumbing4.htm. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ Kermode, Mark (2010-10-22). "Psycho: the best horror film of all time". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2010/oct/22/psycho-horror-hitchcock. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ a b Taylor, Ella (1998-12-09). "Hit the showers: Gus Van Sant's 'Psycho' goes right down the drain". Seattle Weekly. http://web.archive.org/web/20071205070358rn_1/www.seattleweekly.com/1998-12-09/film/hit-the-showers.php. Retrieved 2010-04-17.

- ^ a b Leigh, pp. 105–6

- ^ Leigh, p. 95

- ^ Rebello 1990, p. 21

- ^ a b Leigh, p. 187

- ^ WABC TO TONE DOWN 'PSYCHO' FOR JUNE 24. The New York Times, June 1, 1967. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ Brill 1988, pp. 200–201

- ^ Brill 1988, p. 223

- ^ Brill 1988, p. 224

- ^ Brill 1988, p. 228

- ^ Brill 1988, p. 229

- ^ Brill 1988, p. 225

- ^ Brill 1988, pp. 225–226

- ^ a b c Leigh, pp. 90–93

- ^ a b Kaganski 1997

- ^ Fiennes, Sophie (director); Žižek, Slavoj (writer/narrator) (2006). The Pervert's Guide to Cinema (documentary). Amoeba Film. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0828154.

- ^ a b c d e Leigh, pp. 99–102

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (June 17, 1960). "Screen: Sudden Shocks". The New York Times. http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF173DE273BC4F52DFB066838B679EDE. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ Smith 2009, p. 175

- ^ These are from (in order): New York Times, Newsweek and Esquire

- ^ These are from (in order): New York Daily News, New York Daily Mirror, and Village Voice

- ^ Leigh, p. 141

- ^ Steinberg 1980, p. 13

Hitchcock's second highest moneymaking film was Family Plot ($7,541,000), and third place was a tie between Torn Curtain (1966) and Frenzy (1972), each earning $6,500,000. - ^ a b Leigh, pp. 103–106

- ^ a b Leigh, pp. 180–181

- ^ Hardy 1986, p. 137

- ^ a b Leigh, p. 186

- ^ "100 Scariest Movie Moments". Bravo. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. http://web.archive.org/web/20071030070540/http://www.bravotv.com/The_100_Scariest_Movie_Moments/index.shtml. Retrieved 2009-07-02 (via Internet Archive).

- ^ "The 25 Most Shocking Moments in Movie History". Premiere Magazine. http://beta.premiere.com/List/The-25-Most-Shocking-Moments-in-Movie-History/4.-Psycho. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

- ^ Leigh, p. 113

- ^ Ebert, Roger Psycho III. Roger Ebert' Movie Home Companion. Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel, 1991

- ^ "Psycho III". Variety. 1986-01-01. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117794204.html?categoryid=31&cs=1&p=0. Retrieved 2006-11-26.

- ^ Winecoff 1996[page needed]

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1998-12-06). "Review of Psycho (1998 film)". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/19981206/REVIEWS/812060301/1023. Retrieved 2007-11-03.

- ^ Billington, Alex (5 Nov 2007). Anthony Hopkins Talks About Alfred Hitchcock Presents. www.firstshowing.net

- ^ "Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of a Film Culture". http://www.mysterynet.com/hitchcock/silet/. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "Psycho (1960)". http://filmsdefrance.com/FDF_Psycho_1960_rev.html. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "Psycho Analyzed". http://www.movingimagesource.us/articles/psycho-analyzed-20100302. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ "Alfred Hitchcock Filmmaking Techniques "SUSPENSE ‘HITCHCOCKIAN’"". http://filmdirectors.co/alfred-hitchcock-filmmaking-techniques/. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ Harti, John. "‘Chocolate Factory’ is a tasty surprise" at msnbc.com, July 14, 2005.

- ^ "Alfred Hitchcock: Our Top 10". CNN. 1999-08-13. Archived from the original on December 11, 2004. http://web.archive.org/web/20041211002501/http://edition.cnn.com/SHOWBIZ/specials/1999/hitchcock/best.html. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (1998-12-14). "Psycho Therapy: Gus Van Sant works out his Hitchcock obsession with a reverent remake". TIME. http://strweb1-12.websys.aol.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989844,00.html. Retrieved 2006-12-01.

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "Review: Psycho (1960)". http://www.reelviews.net/movies/p/psycho.html. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Psycho (1960)". Film Site. http://www.filmsite.org/psyc.html. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ^ Busta Rhymes – E.L.E. Extinction Level Event|Album Review @ Music-Critic.com : the source for music reviews, interviews, articles, and news on the internet. Music-critic.com (1998-12-17). Retrieved on 2010-11-21.

- ^ George Khoury and Eric Nolen-Weathington. Modern Masters Volume Six: Arthur Adams, 2006, TwoMorrows Publishing.

- ^ "Psycho Ratings and Certifications". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0054215/parentalguide. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ a b "MPAA Ratings System". Home Theater Info. http://www.hometheaterinfo.com/mpaa.htm. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ "Discovision Library: Psycho". http://www.blamld.com/DiscoVision/Library.htm. Retrieved 2010-11-08.

- ^ UK DVD and Blu-ray Releases: Monday 9th August 2010 -filmdetail.com

- ^ Australian Blu-Ray releases W/C Monday November 29, 2010 -blurayaustralia.com

- ^ Barton, Steve. "Official Cover Art: Psycho on Blu-ray". Dread Central. http://www.dreadcentral.com/news/38019/official-cover-art-psycho-blu-ray. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- Bibliography

- Allen, Richard (2007). Hitchcock's romantic irony. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231135750.

- Brill, Lesley (1988). "'I Look Up, I Look Down' (Vertigo and Psycho)". The Hitchcock Romance: Love and Irony in Hitchcock's Films. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691008221.

- Caminer, Sylvia; Gallagher, John Andrew (January/February 1996). "An Interview with Joseph Stefano.". Films in Review XLVII (1/2).

- Dancyger, Ken (2002). The Technique of Film and Video Editing: History, Theory, and Practice. New York: Focal Press. ISBN 0-2408-0420-1.

- Hardy, Phil (1986). Encyclopedia of Horror Movies. London: Octopus Books. ISBN 0-7064-2771-8.

- Kaganski, Serge (1997). Alfred Hitchcock. Paris: Hazan.

- Krohn (2003). Hitchcock at Work. Phaidon Press Ltd.

- Nickens, Christopher; Leigh, Janet (1996). Psycho: Behind the Scenes of the Classic Thriller. Harmony. ISBN 051770112X.

- Palmer, Christopher (1990). The Composer in Hollywood. London: Marion Boyars. ISBN 0-1745-2950-8.

- Rebello, Stephen (1990). Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho. Marion Boyars. ISBN 0714530034.

- Smith, Joseph W., III. (2009). The Psycho File: A Comprehensive Guide to Hitchcock's Classic Shocker. Berkeley: McFarland.

- Smith, Steven C. (1991). A Heart at Fire's Center; The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22939-8.

- Steinberg, Cobbett (1980). Film Facts. New York: Facts on File, Inc.. ISBN 0-87196-313-2.

- Winecoff, Charles (1996). Split Image: The Life of Anthony Perkins. Diane Pub Co.. ISBN 078819870X.

- Truffaut, François; Helen Scott (1967). Hitchcock (Revised ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-60429-5.

- Wagstaff, Sheena, ed (2004). Edward Hopper. London: Tate Publishing. ISBN 1-85437-533-4.

- Wood, Robin (1989). Hitchcock's Films Revisited. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571162266.

- Further reading

The following publications are among those devoted to the production of Psycho:

- Anobile, Richard J.; editor. Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (The Film Classics Library). Avon Books, 1974. This volume, published before the proliferation of home video, is entirely composed of photo reproductions of film frames along with dialogue captions, creating a fumetti of the entire motion picture.

- Durgnat, Raymond E. A Long Hard Look at Psycho (BFI Film Classics). British Film Institute, 2002.

- Kolker, Robert; editor. Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho: A Casebook. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Leigh, Janet with Christopher Nickens. Psycho: Behind the Scenes of the Classic Thriller. Harmony Press, 1995.

- Naremore, James. Filmguide to Psycho. Indiana University Press, 1973.

- Rebello, Stephen. Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho. Dembner Books, 1990. A definitive "making of" account tracing every stage of the production of the film as well as its aftermath.

- Rebello, Stephen. "Psycho: The Making of Alfred Hitchcock's Masterpiece". "Cinefantastique", April 1986 (Volume 16, Number 4/5). Comprehensive 22-page article.

- Skerry, Philip J. The Shower Scene in Hitchcock's Psycho: Creating Cinematic Suspense and Terror. Edwin Mellen Press, 2005.

- Smith, Joseph W., III. The Psycho File: A Comprehensive Guide to Hitchcock's Classic Shocker. McFarland, 2009.

- Thomson, David, The Moment of Psycho (2009) ISBN 978-0-465-00339-6

External links

- Psycho at the Internet Movie Database

- Psycho at Rotten Tomatoes

- Bright Lights Film Journal article on Psycho

- Filmsite: Psycho In-depth analysis of the film

- Psycho and Bernard Herrmann film score

- "Psycho' at 50: What We've Learned from Alfred Hitchcock's Horror Classic" by Gary Susman – Moviefone – June 15, 2010

Psycho series Robert Bloch's novels - Psycho (1959)

- Psycho II (1982)

- Psycho House (1990)

Films - Psycho (1960)

- Psycho II (1983)

- Psycho III (1986)

- Psycho IV: The Beginning (1990)

- Psycho (1998)

Directors Screenwriters Characters - Norman Bates

- Norma Bates

- Marion Crane

- Lila Crane

- Emma Spool

Other - Bates Motel (1987)

- Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho (1990)

- Robert Bloch's Psychos (1997)

- Psycho (1998)

- Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho (2010)

- The Psycho Legacy (2010)

Wikimedia Alfred Hitchcock Films directed 1920sNumber 13 · The Pleasure Garden · The Blackguard · The Mountain Eagle · The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog · The Ring · Downhill · The Farmer's Wife · Easy Virtue · Champagne · The Manxman · Blackmail1930sJuno and the Paycock · Murder! · The Skin Game · Mary · Rich and Strange · Number Seventeen · Waltzes from Vienna · The Man Who Knew Too Much · The 39 Steps · Secret Agent · Sabotage · Young and Innocent · The Lady Vanishes · Jamaica Inn1940s1950s1960s1970sShortsAlways Tell Your Wife · Elstree Calling · An Elastic Affair · Aventure malgache · Bon Voyage · The Fighting Generation · Watchtower Over Tomorrow

Related topics Categories:- 1960 films

- American films

- English-language films

- Psycho films

- 1960s horror films

- 1960s thriller films

- American mystery films

- American horror films

- American thriller films

- Films directed by Alfred Hitchcock

- Black-and-white films

- Cross-dressing in film and television

- Edgar Award winning works

- Films based on horror novels

- Films based on thriller novels

- Films set in Arizona

- Films set in California

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films shot in California

- Psychological thriller films

- Serial killer films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Pictures films

- Paramount Pictures films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.