- Roman Catholic dogma

-

Statue of Saint Peter at his basilica in Rome. And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose upon earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven. (Gospel of Matthew 16,19)

Statue of Saint Peter at his basilica in Rome. And I will give to thee the keys of the kingdom of heaven. And whatsoever thou shalt bind upon earth, it shall be bound also in heaven: and whatsoever thou shalt loose upon earth, it shall be loosed also in heaven. (Gospel of Matthew 16,19)

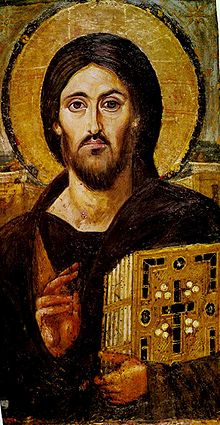

In the Roman Catholic Church, a dogma is an article of faith revealed by God, which the magisterium of the Church presents to be believed[1]. The resurrection of Jesus Christ is the basic truth from which salvation and life is derived for Christians. Dogmata regulate the language, how the truth of the resurrection is to be believed and communicated. One dogma is only a small particle of the living Christian faith, from which it derives its meaning.[2] Roman Catholic Dogma is thus: "a truth revealed by God, which the magisterium of the Church declared as binding."[3] The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

- The Church's Magisterium exercises the authority it holds from Christ to the fullest extent when it defines dogmas, that is, when it proposes, in a form obliging the Christian people to an irrevocable adherence of faith, truths contained in divine Revelation or also when it proposes, in a definitive way, truths having a necessary connection with these. [4]

The faithful are required to accept with the divine and Catholic faith all which the Church presents either as solemn decision or as general teaching. Yet not all teachings are dogma. The faithful are only required to accept those teachings as dogma, if the Church clearly and specifically identifies them as infallible dogmata.[5] Not all truths are dogmata. The Bible contains many sacred truths, which the faithful recognize and agree with, but which the Church has not defined as dogma. Most Church teachings are not dogma. Cardinal Avery Dulles points out that in the 800 pages of the documents of the Second Vatican Council, there is not one new statement for which infallibility is claimed.[6]

Contents

Elements: Scripture and Tradition

The concept of dogma has two elements: Immediate divine revelation from Scripture or Tradition, and, a proposition of the Church, which not only announces the dogma but also declares it binding for the faith. This may occur through an ex-cathedra decision by a Pope, or by an Ecumenical Council.[7]

The Holy Scripture is not identical with divine revelation, but a part of it. Jesus Christ taught only orally and instructed his disciples to teach orally. Early Christians lived from oral traditions, as scriptures did not yet exist. "Keep as your pattern the sound teaching you have heard from me, in the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus.“ [8][9] Scriptures were written later by apostles and evangelists, who knew Jesus. They give infallible testimony of his teachings.[9] Scripture thus belongs to Tradition in the larger sense, where it has an absolute priority, because it is the Word of God, and because it is the unchangeable testimony of the apostles of Christ, whose fullness the Church preserves with its tradition.[10]

Dogma as divine and Catholic faith

Part of a series on the Catholic Church

Organisation Pope – Pope Benedict XVI College of Cardinals – Holy See Ecumenical Councils Episcopal polity · Latin Church Eastern Catholic Churches Background History · Christianity Catholicism · Apostolic Succession Four Marks of the Church Ten Commandments Crucifixion & Resurrection of Jesus Ascension · Assumption of Mary Theology Trinity (Father, Son, Holy Spirit) Theology · Apologetics Divine Grace · Sacraments Purgatory · Salvation Original sin · Saints · Dogma Virgin Mary · Mariology Immaculate Conception of Mary Liturgy and Worship Roman Catholic Liturgy Eucharist · Liturgy of the Hours Liturgical Year · Biblical Canon Rites Roman · Armenian · Alexandrian Byzantine · Antiochian · West Syrian · East Syrian Controversies Science · Evolution · Criticism Sex & gender · Homosexuality Catholicism topics Monasticism · Women · Ecumenism Prayer · Music · Art Catholicism portal

Dogma is considered to be both divine and Catholic faith. Divine, because of its believed origin and Catholic because of belief in the infallible teaching binding for all.[11] At the turn of the 20th century, a group of theologians called modernists stated that dogmata did not fall from heaven but are historical manifestations at a given time. Pope Pius X condemned this teaching as heresy in 1907.[12] The Catholic position is that the content of a dogma has truly divine origin. It is considered an expression of an objective truth and does not change.[13] The truth of God, revealed by God, does not change, as God himself does not change; Heaven and earth will disappear but my words will not disappear.[14]

However, new dogmata can be declared through the ages. For instance, the 20th century witnessed the introduction of the dogma of Assumption of Mary by Pope Pius XII in 1950.[15] However, these beliefs were already held in some form or another within the Church before their elevation to the dogmatic level. A movement to declare a fifth Marian dogma for Mediatrix and Co-Redemptrix is underway.[16]

Early uses of the term

The term Dogma Catholicum was first used by Vincent of Lérins (450), referring to “what all, everywhere and always believed” [17] In the year 565, Emperor Justinian declared the decisions of the first ecumenical councils as law because they are true dogmata of God [17] In the Middle Ages, the term Doctrina Catholica, (Catholic doctrine) was used for the Catholic faith. Individual beliefs were labeled as Articulus Fidei ( part of the faith)

Ecumenical Councils issue dogmas. Many dogmata - especially from the early Church (Ephesus, Chalcedon) to the Council of Trent - were formulated against specific heresies.(Holy Spirit only emanating from father and not from Father and Son) Later dogmas (Immaculate Conception and Assumption of Mary) express the greatness of God in binding language. At the specific request of Pope John XXIII, the Second Vatican Council did not proclaim any dogmas. Instead it presented the basic elements of the Catholic faith in a more understandable, pastoral language, without changing the teachings of the Church.[2] The last two dogmas were pronounced by Popes, Pope Pius IX in 1854 and Pope Pius XII in 1950 on the Immaculate Conception and the assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary respectively. They are cornerstones of Mariology(Roman Catholic)

To some, this raises the question, why “new” dogmas are formulated almost 2000 years after the resurrection of Christ. It is Catholic teaching that with Christ and the Apostles, revelation is completed. Dogmata issued after the death of his apostles are not new, but explications of existing faith. Implicit truth are specified as explicit, as it was done in the teachings on the Trinity by the ecumenical councils. Karl Rahner tries to explain this with the allegorical sentence of a husband to his wife “ I love you” this surely implies, I am faithful to you.[18] In 450 Vincent of Lérins asked in his famous Commonitory, Will there be no progress in religion in the Church of Christ? Of course there will be progress. There will be much progress, but it will be progress in truth and faith, not change. Progress means addition, change means alteration. [19]

But he warns: “What is entrusted to you, not what you invented. What you received, not what you imagined, not a matter of reason but of teaching, not your preferences but public tradition, what you were given, not what you produced, …you received gold, give gold back.” [20] The Church uses this text in its interpretation of dogmatic development: The first Vatican Council stated in 1870 that within the limits of the statement of Vincent of Lérins, dogmatic development is possible,[21] Vatican II confirms this view in Lumen Gentium.[22]

Theological certainties

The Magisterium of the Church is directed to guard, preserve and teach divine truths which God has revealed with infallibility (De fide). A rejection of Church Magisterial teachings is a de facto rejection of divine revelation. It is considered the mortal sin of heresy if the heretical opinion is held with full knowledge of the Church's opposing dogmata. The infallibility of the Magisterium extends also to teachings which are deduced from such truths (Fides ecclesiastica). These Church teachings or Catholic truths (veritates catholicae) are not a part of divine revelation, yet are intimately related to it. The rejection of these "secondary" teachings is not heretical, but involves the impairment of full communion with the Catholic Church.

There are three categories of these "secondary" teachings (Fides ecclesiastica):

- Theological conclusions: (conclusiones theologicae) religious truths, deduced from divine revelation and reason, such as the impossibility of ordaining women, and the illicitness of euthanasia.

- Dogmatic facts (facta dogmatica) historical facts, not part of revelation but clearly related to it. For example the legitimacy of the papacy of Pope Benedict XVI, and the Petrine office

- Philosophical truths, such as existence of the soul, "freedom of will", philosophical definitions used in dogmas such as transubstantiation

Theological certainty Description 1. De fide Divine revelations with the highest degree of certainty, considered infallible revelation 2. Fides ecclesiastica Church teachings, which have been definitively decided on by the Magisterium, considered infallible revelation 3. Sententia fidei proxima Church teachings, which are generally accepted as divine revelation but not defined as such by the magisterium 4. Theologica certa Church teachings without final approval but clearly deduced from revelation 5. Sententia communis Teachings which are popular but within the free range of theological research 6. Sententia probabilis Teachings with low degree of certainty 7. Opinio tolerata Opinions tolerated within the Catholic Church, such as pious legends Papal bulls and encyclicals

Pope Pius XII stated in Humani Generis, that Papal Encyclicals, even when they are not ex cathedra, can nonetheless be sufficiently authoritative to end theological debate on a particular question:

“ It is not to be thought that what is set down in Encyclical letters does not demand assent in itself, because in this the popes do not exercise the supreme power of their magisterium. For these matters are taught by the ordinary magisterium, regarding which the following is pertinent: “He who heareth you, heareth Me.” (Luke 10:16); and usually what is set forth and inculcated in Encyclical Letters, already pertains to Catholic doctrine. But if the Supreme Pontiffs in their acts, after due consideration, express an opinion on a hitherto controversial matter, it is clear to all that this matter, according to the mind and will of the same Pontiffs, cannot any longer be considered a question of free discussion among theologians.

- —Humani Generis

” The end of the theological debate is not identical however with dogmatization. Throughout the history of the Church, its representatives have discussed whether a given Papal teaching is the final word or not.

In 1773, Father Lorenzo Ricci, hearing rumours that Pope Clement XIV might dissolve his Jesuit order, wrote "it is most incredible that the Deputy of Christ would state the opposite, what his predecessor Clement XIII stated in the Papal Bull Apostolicum, in which he defended and protected us." When a few days later he was asked if he would accept the Papal Breve, reverting Clement XIII and dissolving the Jesuit Order, Father Ricci replied, whatever the Pope decides must be sacred to everybody.[23]

In 1995, questions arose as to whether the Apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, exempting women from ordination is to be understood as belonging to the deposit of faith. Wherefore, in order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter of great importance, a matter which pertains to the Church's divine constitution itself, in virtue of Our ministry of confirming the brethren (cf. Lk 22:32) We declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful.[24]

Critics of Ordinatio Sacerdotalis[25] point out, that it was not issued under the extraordinary papal magisterium as an ex cathedra statement, and so is not considered infallible in itself. Its contents are, however, considered infallible under the ordinary magisterium. The American Cardinal Avery Dulles, in a lecture to US bishops stated that Ordinatio Sacerdotalis is infallible, not because of the Apostolic Letter or the clarification by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger alone, but because it is based on a wide range of sources, scriptures, the constant tradition of the Church and the ordinary and universal magisterium of the Church: Pope John Paul II had identified a truth infallibly taught over two thousand years by the Church.[26]

Apparitions and dogma

Statue of Our Lady of Lourdes. The Lourdes apparitions occurred four years after the definition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception.

Apparitions have taken place within the Church since the very beginning and are a part of the apostolic tradition, since many examples of apparitions exist in the Holy Scriptures. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states:

- Throughout the ages, there have been so-called "private" revelations, some of which have been recognized by the authority of the Church. They do not belong, however, to the deposit of faith. It is not their role to improve or complete Christ's definitive Revelation, but to help live more fully by it in a certain period of history. Guided by the Magisterium of the Church, the sensus fidelium knows how to discern and welcome in these revelations whatever constitutes an authentic call of Christ or his saints to the Church.

Apparitions are considered to be welcome charismatic expressions of the faith. God permits the appearance of (Christ, Mary, Saints) to individuals. When the Church confirms that divine revelations to individual persons have taken place, she permits veneration. Such approvals do not constitute dogma. Marian apparitions are an example of such revelations. Although Popes approve Marian apparitions, promote them, or participate in related veneration, respectful distance even disapproval of such papal teachings is possible.

The Church views apparitions not as dogmatic innovations but as an prophetic impulses, which reflame and renew the faith. Marian apparitions bring millions of people together and recreate faith, vigour, unity and solidarity, within the Mystical Body of Christ For those, convinced certain about certainty of the divine origin, the apparition is Fides Divina. Apparitions and other private revelations are never Veritates Catolicae, or Catholic teachings, because this would imply, that God improved his own revelation. for this reason specific apparitions and private revelations are usually not subject of dogmatic publications. The Catholic Church rejects " private revelations" of Christian sects and non-Christian groups, that claim to surpass or correct the Revelation of Jesus Christ.[27]

Ecumenical aspects

Protestant theology since the reformation was largely negative on the term dogma. This changed in the 20th century, when Karl Barth with his Kirchliche Dogmatik, stated the need for systematic and binding articles of faith.[28] The Creed is the most comprehensive – but not complete - summary of important Catholic dogmas. (It was originally used during baptism ceremonies). The Creed is a part of Sunday liturgy. Because many Protestant Churches have retained the older versions of the Creed, ecumenical working groups are meeting to discuss the Creed as the basis for better understandings of dogma.[29]

Sources

- Wolfgang Beinert Lexikon der katholischen Dogmatik, Herder, Freiburg, 1988

- Avery Dulles, The Survival of Dogma, Faith, authority and dogma in a changing world, Image Book, New York, 1970

- Avery Dulles, The Changing forms of faith, Alexandria, Virginia, 1970

- Avery Dulles, Doctrinal authority of the Church, in Theology in Revolution, Alba House, Staten Island, 1970

- J.B.Heinrich, Lehrbuch der katrholischen Dogmatik, Verlag der Aschaffendorfischen Buchhandlung, Münster 1900 (1939)

- Ludwig Ott Grundriss der Dogmatik Herder, Freiburg 1965

- Karl Rahner, Theology and the Magisterium, Theological digest, 1968, 4-17

- Karl Rahner, Historical dimensions in Theology, Theology difest, 1968, 30-42

- Karl Rahner, What is a dogmatic statement, Theological Investigations, 5 1966, 42-66

- Francis Simmons, Infallibility and the Evidence, Springfield, Ill, 1968

- Michael Schmaus, Katholische Dogmatik, München 1955 (1982)

References

- ^ (The terms dogma, truth, divine truth, infallible etc., are to be understood as relating only to Catholic doctrine.)

- ^ a b Beinert 90

- ^ Schmaus, I, 54

- ^ Catechism 88

- ^ Schmaus, 54

- ^ Dulles, 147

- ^ Ott 5

- ^ 2 Tim 13

- ^ a b Heinrich, 52

- ^ Heinrich 52

- ^ Ott, 5

- ^ encyclical Pascendi.

- ^ Ott 6

- ^ Mk 13,31

- ^ Mark Miravalle, 1993, Introduction to Mary, Queenship Publishing ISBN 9781882972067 page 51

- ^ Mark Miravalle, 1993 "With Jesus": the story of Mary Co-redemptrix ISBN 1579182410 page 11

- ^ a b Beinert 89

- ^ Schmaus, 40

- ^ Commonitorium22

- ^ Vincent of Lérins Commonitorium 22 BKV 55

- ^ Beinert 96

- ^ Lumen Gentium 12

- ^ Ludwig von Pastor, Geschichte der Päpste, XVI,2 1961, 207-208

- ^ (Declaramus Ecclesiam facultatem nullatenus habere ordinationem sacerdotalem mulieribus conferendi, hancque sententiam ab omnibus Ecclesiae fidelibus esse definitive tenendam.)

- ^ such as the Catholic theological society of America George Weigel, Witness to Hope, A biography of Pope John Paul II Harper New York 2005, p. 732, 733

- ^ Weigel, 732, 733

- ^ Apparitions in the Holy Scriptures. Mt 1,20, 2,12, 12,19; LK 9,8; 1 Cor,15,8 The Catechism of the Catholic Church 67 Apparitions are considered Schmaus 55. The Church views Beinert 339 Apparitions never Veritates Catolicae, Heinrch 45 for this reason specific apparitions and private revelations are usually not subject of dogmatic publications. The Catholic Church rejects " private revelations" Catechism 67

- ^ Zollikon Zürich 1032-1970 Beinert 92

- ^ Beinert 199

Categories:- Catholic theology and doctrine

- Catholic doctrines

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.