- Combined small-cell lung carcinoma

-

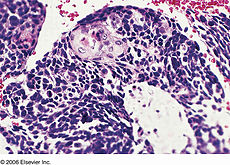

Combined Small Cell Lung Carcinoma Classification and external resources

Combined small cell lung carcinoma containing a component of squamous cell carcinomaICD-10 C33-C34 ICD-9 162 ICD-O: 8045/3 DiseasesDB 7616 MedlinePlus 007194 eMedicine med/ MeSH D018288 Combined small cell lung carcinoma (c-SCLC) is a form of multiphasic lung cancer that is diagnosed when a malignant tumor arising from lung tissue contains a component of small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) admixed with one (or more) components of non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC).[1][2][3]

Contents

Classification

Lung cancer is a large and exceptionally heterogeneous family of malignancies.[4] Over 50 different histological variants are explicitly recognized within the 2004 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) typing system ("WHO-2004"), currently the most widely used lung cancer classification scheme.[1] Many of these entities are rare, recently described, and poorly understood.[5] However, since different forms of malignant tumors generally exhibit diverse genetic, biological, and clinical properties, including response to treatment, accurate classification of lung cancer cases are critical to assuring that patients with lung cancer receive optimum management.[6][7]

Approximately 98% of lung cancers are carcinoma, a term for malignant neoplasms derived from cells of epithelial lineage, and/or that exhibit cytological or tissue architectural features characteristically found in epithelial cells.[8] Under WHO-2004, lung carcinomas are divided into 8 major taxa:[1]

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Small cell carcinoma

- Adenocarcinoma

- Large cell carcinoma

- Adenosquamous carcinoma

- Sarcomatoid carcinoma

- Carcinoid tumor

- Salivary gland-like carcinoma

SCLC is generally considered to be the most aggressive form of lung cancer, with the worst long term prognosis and survival rates.[8] Therefore, all tumor(s) containing SCLC cells are classified as c-SCLC, and not as combined forms of any other components(s) present, regardless of their relative proportions.[1] The only exception occurs in cases where anaplastic large cell lung carcinoma (LCLC) is the second component. In these instances, a minimum of 10% of the malignant cells must be identified as LCLC before the tumor is considered a c-SCLC.[1][9] Under WHO-2004, c-SCLC is the only recognized variant of SCLC.[1]

Incidence

Reliable comprehensive incidence statistics for c-SCLC are unavailable. In the literature, the frequency with which the c-SCLC variant is diagnosed largely depends on the size of tumor samples, tending to be higher in series where large surgical resection specimens are examined, and lower when diagnoses are based on small cytology and/or biopsy samples. Tatematsu et al. reported 15 cases of c-SCLC (12%) in their series of 122 consecutive SCLC patients, but only 20 resection specimens were examined.[10] In contrast, Nicholson et al. found 28 c-SCLC (28%) in a series of 100 consecutive resected SCLC cases.[9] It appears likely, then, that the c-SCLC variant comprises 25% to 30% of all SCLC cases.[11][12]

As the incidence of SCLC has declined somewhat in the U.S. in recent decades,[13] it is likely that c-SCLC has also decreased in incidence. Nevertheless, small cell carcinomas (including the c-SCLC variant) still comprise 15%–20% of all lung cancers, with c-SCLC probably accounting for 4%–6%.[14] With 220,000 cases of newly diagnosed lung cancer in the U.S. each year, it can be estimated that between 8,800 and 13,200 of these are c-SCLC.[15]

In a study of 408 consecutive patients with SCLC, Quoix and colleagues found that presentation as a solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) is particularly indicative of a c-SCLC - about 2/3 of their SPN's were pathologically confirmed to be c-SCLC's containing a large cell carcinoma component.[16]

Significance

In terms of case numbers, the estimated 8,800 to 13,200 c-SCLC cases occurring annually in the U.S. makes this disease roughly comparable in incidence to Hodgkin's Disease (8,500), testicular cancer (8,400), cervical cancer (11,300), and cancers of the larynx (12,300).[15] However, these four "better-known" cancers all have exceptionally high (85%-95%) cure rates. In contrast, less than 10% of c-SCLC patients will be cured, and thus the number of annual cases of c-SCLC is a reasonable approximation of the annual number of deaths. Therefore, given the significant incidence and mortality attributable to this malignancy,[17] (see Prognosis and survival) it is arguably critical to better understand these aggressive lesions so specific strategies for their management can be rationally designed.[6][7][18]

However, as patients with tumors containing mixtures of histological subtypes are usually excluded from clinical trials,[19] the properties of multiphasic tumors like c-SCLC are much less well understood than those of monophasic tumors.[20] C-SCLC contains both SCLC and NSCLC by definition, and since patients with SCLC and NSCLC are usually treated differently, the lack of good data on c-SCLC means there is little evidence available with which to form consensus about whether c-SCLC should be treated like SCLC, NSCLC, or uniquely.[21]

Histogenesis

In most cases, lung cancers probably result from the malignant transformation of a single multipotent cell. This newly formed cancer stem cell then begins to divide uncontrollably, giving rise to new daughter cancer cells in an exponential (or near exponential) fashion. Unless this runaway cell division process is checked, a clinically apparent tumor will eventually form.[22]

Approximately 98% of lung cancers are carcinoma, a term which implies that the tumor derives from transformed epithelial cells, or consists of cells that have acquired epithelial characteristics as a result of cell differentiation.[8] In most cases of c-SCLC, genomic and immunohistochemical studies suggest that the morphological divergence of the separate components in a c-SCLC occurs when a SCLC-like cell is transformed into a cell with the potential to develop NSCLC variant characteristics, and not vice versa. Daughter cells of this transdifferentiated SCLC-like cell then repeatedly divide and, under both intrinsic genomic and extrinsic environmental influences, acquire additional mutations, a process known as tumor progression. The end result is that the tumor acquires specific cytologic and architectural features suggesting a mixture of SCLC and NSCLC.[12]

Other molecular studies, however, suggest that - in at least a minority of cases - independent development of the components in c-SCLC occurs via mutation and transformation in two different cells in close spatial proximity to each other, due to field cancerization. In these cases, repeated division and mutational progression in both cancer stem cells generate a biclonal collision tumor.[23][24]

Regardless of which of these mechanisms give rise to the tumor, recent studies suggest that, in the later stages of c-SCLC oncogenesis, continued mutational progression within each tumor component results in the cells of the combined tumor developing molecular profiles that more closely resemble each other than they do cells of the "pure" forms of the individual morphological variants.[25] This molecular oncogenetic convergence likely has important implications for treatment of these lesions, given the differences between standard therapeutic regimens for SCLC and NSCLC.

C-SCLC also occurs quite commonly after treatment of "pure" SCLC with chemotherapy and/or radiation, probably as a result of a combination of tumor genome-specific "progressional" mutations, stochastic genomic phenomena, and additional mutations induced by the cytotoxic therapy.[26][27][28][29]

The most common forms of NSCLC identified as components within c-SCLC are large cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and squamous cell carcinoma.[2][4][20] Rarer variants of NSCLC are seen less commonly, such as combinations with carcinoids,[20] spindle cell carcinoma,[2][3] and giant cell carcinoma.[9] Giant cell carcinoma components are seen much more commonly in patients who have undergone radiation.[30][31][32] With the approval and use of newer "molecularly targeted" agents revealing differential efficacies in specific subtypes and variants of NSCLC, it is becoming more important for pathologists to correctly subclassify NSCLC's as distinct tumor entities, or as components of c-SCLC's.

Staging

Staging of c-SCLC patients is usually performed in an analogous fashion to patients with "pure" small cell lung carcinoma.

For several decades, SCLC has been staged according to a dichotomous distinction of "limited disease" (LD) vs. "extensive disease" (ED) tumor burdens.[33][34] Nearly all clinical trials have been conducted on SCLC patients staged dichotomously in this fashion.[35] LD is roughly defined as a locoregional tumor burden confined to one hemithorax that can be encompassed within a single, tolerable radiation field, and without detectable distant metastases beyond the chest or supraclavicular lymph nodes. A patient is assigned an ED stage when the tumor burden is greater than that defined under LD criteria - either far advanced locoregional disease, malignant effusions from the pleura or pericardium, or distant metastases.[36]

However, more recent data reviewing outcomes in very large numbers of SCLC patients suggests that the TNM staging system used for NSCLC is also reliable and valid when applied to SCLC patients, and that more current versions may allow better treatment decisionmaking and prognostication in SCLC than with the old dichotomous staging protocol.[33][37][38]

Treatment

A very large number of clinical trials have been conducted in "pure" SCLC over the past several decades.[35] As a result, evidence-based sets of guidelines for treating monophasic SCLC are available.[11][21] While the current set of SCLC treatment guidelines recommend that c-SCLC be treated in the same manner as "pure" SCLC, they also note that the evidence supporting their recommendation is quite weak.[21] It is likely, then, that the optimum treatment for patients with c-SCLC remains unknown.[20]

The current generally accepted standard of care for all forms of SCLC is concurrent chemotherapy (CT) and thoracic radiation therapy (TRT) in LD, and CT only in ED. For complete responders (patients in whom all evidence of disease disappears), prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) is also given. TRT serves to increase the probability of total eradication of residual locoregional disease, while PCI aims to eliminate any micrometastases to the brain.[21]

Surgery is not often considered as a treatment option in SCLC (including c-SCLC) due to the high probability of distant metastases at the time of diagnosis.[39] This paradigm was driven by early studies showing that the administration of systemic therapies resulted in improved survival as compared to patients undergoing surgical resection.[40][41][42] Recent studies, however, have suggested that surgery for highly selected, very early-stage c-SCLC patients may indeed improve outcomes.[43] Other experts recommend resection for residual masses of NSCLC components after complete local tumor response to chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy in c-SCLC.[44]

Although other combinations of drugs have occasionally been shown to be noninferior at various endpoints and in some subgroups of patients, the combination of cisplatin or carboplatin plus etoposide or irinotecan are considered comparable first-line regimens for SCLC.[21][45] For patients who do not respond to first line therapy, or who relapse after complete remission, topotecan is the only agent which has been definitively shown to offer increased survival over best supportive care (BSC),[21][46] although in Japan amirubicin is considered effective as salvage therapy.[46]

Importantly, c-SCLC is usually much more resistant to CT and RT than "pure" SCLC.[27][29][47][48][49][50] While the mechanisms for this increased resistance of c-SCLC to conventional cytotoxic treatments highly active in "pure" SCLC remain mostly unknown, recent studies suggest that the earlier in its biological history that a c-SCLC is treated, the more likely it is to resemble "pure" SCLC in its response to CT and RT.[25][26][27][28]

Targeted agents

In recent years, several new types of "molecularly targeted" agents have been developed and used to treat lung cancer. While a very large number of agents targeting various molecular pathways are being developed and tested, the main classes and agents that are now being used in lung cancer treatment include:[51]

- Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs):[52]

- Inhibitors of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)[56]

- Bevacizumab (Avastin)[57]

- Inhibitors of folate metabolism[58]

- Pemetrexed (Alimta)[59]

To date, most clinical trials of targeted agents, alone and in combination with previously tested treatment regimens, have either been ineffective in SCLC or no more effective than standard platinum-based doublets.[60][61][62][63] While there have been no randomized clinical trials of targeted agents in c-SCLC,[64] some small case series suggest that some may be useful in c-SCLC. Many targeted agents appear more active in certain NSCLC variants. Given that c-SCLC contains components of NSCLC, and that the chemoradioresistance of NSCLC components impact the effectiveness of c-SCLC treatment, these agents may permit the design of more rational treatment regimens for c-SCLC.[6][7][65]

EGFR-TKI's have been found to be active against variants exhibiting certain mutations in the EGFR gene.[66][67][68][69] While EGFR mutations are very rare (<5%) in "pure" SCLC, they are considerably more common (about 15%-20%) in c-SCLC,[10][70] particularly in non-smoking females whose c-SCLC tumors contain an adenocarcinoma component. These patients are much more likely to have classical EGFR mutations in the small cell component of their tumors as well, and their tumors seem to be more likely to respond to treatment with EGFR-TKI's.[70][71][72] EGFR-targeted agents appear particularly effective in papillary adenocarcinoma,[73][74] non-mucinous bronchioloalveolar carcinoma,[75] and adenocarcinoma with mixed subtypes.[74]

The role of VEGF inhibition and bevacizumab in treating SCLC remains unknown. Some studies suggest it may, when combined with other agents, improve some measures of survival in SCLC patients[76][77] and in some non-squamous cell variants of NSCLC.[76][7][65]

Pemetrexed has been shown to improve survival in non-squamous cell NSCLC, and is the first drug to reveal differential survival benefit in large cell lung carcinoma.[7][78]

Interestingly, c-SCLC appear to express female hormone (i.e. estrogen and/or progesterone) receptors in a high (50%-67%) proportion of cases, similar to breast carcinomas.[79] However, it is at present unknown whether blockade of these receptors affects the growth of c-SCLC.

Prognosis and survival

Current consensus is that the long-term prognosis of c-SCLC patients is determined by the SCLC component of their tumor, given that "pure" SCLC seems to have the worst long-term prognosis of all forms of lung cancer.[8] Although data on c-SCLC is very sparse,[20] some studies suggest that survival rates in c-SCLC may be even worse than that of pure SCLC,[80][81] likely due to the lower rate of complete response to chemoradiation in c-SCLC, although not all studies have shown a significant difference in survival.[82]

Untreated "pure" SCLC patients have a median survival time of between 4 weeks and 4 months, depending on stage and performance status at the time of diagnosis.[21][42]

Given proper multimodality treatment, SCLC patients with limited disease have median survival rates of between 16 and 24 months, and about 20% will be cured.[21][42][44][83] In patients with extensive disease SCLC, although 60% to 70% will have good-to-complete responses to treatment, very few will be cured, with a median survival of only 6 to 10 months.[21][83]

Some evidence suggests that c-SCLC patients who continue to smoke may have much worse outcomes after treatment than those who quit.[84]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Travis, William D; Brambilla, Elisabeth; Muller-Hermelink, H Konrad et al., eds (2004). Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press. ISBN 92 832 2418 3. http://www.iarc.fr/en/publications/pdfs-online/pat-gen/bb10/bb10-cover.pdf. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b c Gotoh, Masashi; Yamamoto, Yasumichi; Huang, Cheng-Long; Yokomise, Hiroyasu (2004). "A combined small cell carcinoma of the lung containing three components: small cell, spindle cell and squamous cell carcinoma". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (Elsevier) (26): 1047–9. http://ejcts.ctsnetjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/26/5/1047. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ^ a b Fouad Ismail M, Mowafy AA, Sameh SI. A combined small cell carcinoma of the lung containing three components: small cell, spindle cell and squamous cell carcinoma, revisited. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005 Apr;27(4):734; author reply 735.

- ^ a b Roggli VL, Vollmer RT, Greenberg SD, McGavran MH, Spjut HJ, Yesner R. Lung cancer heterogeneity: a blinded and randomized study of 100 consecutive cases. Hum Pathol 1985; 16: 569-79.

- ^ Brambilla E, Travis WD, Colby TV, Corrin B, Shimosato Y. The new World Health Organization classification of lung tumours. Eur Respir J 2001;18:1059-68

- ^ a b c Rossi G, Marchioni A, Sartori1 G, Longo L, Piccinini S, Cavazza A. Histotype in non-small cell lung cancer therapy and staging: The emerging role of an old and underrated factor. Curr Resp Med Rev 2007; 3: 69-77.

- ^ a b c d e Vincent MD. Optimizing the management of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a personal view. Curr Oncol 2009; 16: 9-21.

- ^ a b c d Travis WD, Travis LB, DeVesa SS. Lung Cancer. Cancer 1995; 75: 191-202.

- ^ a b c Nicholson SA, Beasley MB, Brambilla E, Hasleton PS, Colby TV, Sheppard MN, Falk R, Travis WD. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC): a clinicopathologic study of 100 cases with surgical specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 2002; 26: 1184-97.

- ^ a b Tatematsu A, Shimizu J, Murakami Y, Horio Y, Nakamura S, Hida T, Mitsudomi T, Yatabe Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 6092-6.

- ^ a b NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Small Cell Lung Cancer V.1.2010. National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

- ^ a b Wagner PL, Kitabayashi N, Chen YT, Saqi A (March 2009). "Combined small cell lung carcinomas: genotypic and immunophenotypic analysis of the separate morphologic components". Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 131 (3): 376–82. doi:10.1309/AJCPYNPFL56POZQY. PMID 19228643. http://ajcp.ascpjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=19228643.

- ^ Dowell JE. Small cell lung cancer: are we making progress? Am J Med Sci 2010;339:68-76.

- ^ Stupp R, Monnerat C, Turrisi AT 3rd, Perry MC, Leyvraz S. Small cell lung cancer: state of the art and feature perspectives. Lung Cancer 2004; 45: 105–17.

- ^ a b American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2009.

- ^ Quoix E, Fraser R, Wolkove N, Finkelstein H, Kreisman H. Small cell lung cancer presenting as a solitary pulmonary nodule. Cancer 1990;66:577-82.

- ^ Sher T, Dy GK, Adjei AA. Small cell lung cancer. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:355-67.

- ^ Moran CA, Suster S, Coppola D, Wick MR. Neuroendocrine carcinomas of the lung: a critical analysis. Am J Clin Pathol 2009, 131:206-21.

- ^ http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/search

- ^ a b c d e Ruffini E, Rena O, Oliaro A, Filosso PL, Bongiovanni M, Arslanian A, Papalia E, Maggi G. Lung tumors with mixed histologic pattern. Clinico-pathological characteristics and prognostic significance. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;22:701-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Simon GR, Turrisi A, American College of Chest Physicians. Management of small cell lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest 2007; 132(3 Suppl):324S-39S.

- ^ Croce CM. Oncogenes and cancer. NEJM 2008;358:502–11.

- ^ Buys TP, Aviel-Ronen S, Waddell TK, Lam WL, Tsao MS. Defining genomic alteration boundaries for a combined small cell and non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:227-39.

- ^ Knudson AG. Two genetic hits (more or less) to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2001;1:157–62.

- ^ a b D'Adda T, Pelosi G, Lagrasta C, Azzoni C, Bottarelli L, Pizzi S, Troisi I, Rindi G, Bordi C. Genetic alterations in combined neuroendocrine neoplasms of the lung. Mod Pathol 2008;21:414-22.

- ^ a b Morinaga R, Okamoto I, Furuta K, Kawano Y, Sekijima M, Dote K, Satou T, Nishio K, Fukuoka M, Nakagawa K. Sequential occurrence of non-small cell and small cell lung cancer with the same EGFR mutation.Lung Cancer 2007;58:411-3.

- ^ a b c Mangum MD, Greco FA, Hainsworth JD, Hande KR, Johnson DH. Combined small cell and non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1989;7:607-612.

- ^ a b Benfield JR, Russell LA. Lung carcinomas. In: Baue A, Geha A, Hammond G, Lakes H, Naunheim K, editors. Glenn's thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 6th ed.. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange; 1996. pp. 357-389.

- ^ a b Brambilla E, Moro D, Gazzeri S, Brichon PY, Nagy-Mignotte H, Morel F, Jacrot M, Brambilla C. Cytotoxic chemotherapy induces cell differentiation in small cell lung carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 1991;9:50-61.

- ^ Erenpreisa J, Ivanov A, Wheatley SP, Kosmacek EA, Ianzini F, Anisimov AP, Mackey M, Davis PJ, Plakhins G, Illidge TM. Endopolyploidy in irradiated p53-deficient tumour cell lines: persistence of cell division activity in giant cells expressing Aurora-B kinase. Cell Biol Int 2008;32:1044-56.

- ^ Illidge T, Cragg M, Fringe B, Olive P, Erenpreisa Je. Polyploid giant cells provide a survival mechanism for p53 mutant cells after DNA damage. Cell Biol Int 2000;24:621–33.

- ^ Higashi K, Clavo AC, Wahl RL. In vitro assessment of 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose, L-methionine and thymidine as agents to monitor the early response of a human adenocarcinoma cell line to radiotherapy. J Nucl Med 1993;34:773-9.

- ^ a b Travis WD; IASLC Staging Committee. Reporting lung cancer pathology specimens. Impact of the anticipated 7th Edition TNM classification based on recommendations of the IASLC Staging Committee. Histopathology 2009;54:3-11.

- ^ Zelen M. Keynote address on biostatistics and data retrieval. Cancer Chemother Rep 1973;4:31–42.

- ^ a b http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/results/lung

- ^ http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/small-cell-lung/HealthProfessional/page4

- ^ Wittekind C, Greene FL, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Sobin LH eds. Lung. In Wittekind C, Greene FL, Henson DE, Hutter RVP, Sobin LH eds. UICC International Union Against Cancer, TNM Supplement: a commentary on uniform use. 3rd edn. New York: Wiley-Liss, 2003;47,97-8,143–49.

- ^ Shepherd FA, Crowley J, Van HP et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer lung cancer staging project: proposals regarding the clinical staging of small cell lung cancer in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the tumor, node, metastasis classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:1067–1077.

- ^ Ihde DC. Current status of therapy for small cell carcinoma of the lung. Cancer 1984;54:2722-8.

- ^ Lennox SC, Flavell G, Pollock DJ, Thompson VC, Wilkins JL. Results of resection for oat-cell carcinoma of the lung. Lancet 1968;2:925-7.

- ^ Fox W, Scadding JG. Medical Research Council comparative trial of surgery and radiotherapy for primary treatment of small-celled or oat-celled carcinoma of bronchus: ten-year follow-up. Lancet 1973;2:63-65.

- ^ a b c http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/small-cell-lung/HealthProfessional/page2

- ^ Hage R, Elbers JR, Brutel de la Riviere A, van den Bosch JM. Surgery for combined type small cell lung carcinoma. Thorax 1998;53:450–3.

- ^ a b Shepherd FA, Ginsberg R, Patterson GAet al. Is there ever a role for salvage operations in limited small-cell lung cancer? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101(2):196-200.

- ^ Hann CL, Rudin CM. Management of small-cell lung cancer: incremental changes but hope for the future. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008;22:1486-92.

- ^ a b Nakamura Y, Yamamoto N.[Second-line treatment and targeted therapy of advanced lung cancer] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2009;36:710-6. [Article in Japanese] [Abstract].

- ^ Wagner PL, Kitabayashi N, Chen YT, Saqi A. Combined small cell lung carcinomas: genotypic and immunophenotypic analysis of the separate morphologic components. Am J Clin Pathol 2009;131:376-82.

- ^ Adelstein DJ, Tomashefski JF Jr, Snow NJ et al.. Mixed small cell and non–small cell lung cancer. Chest 1986;89:699–704.

- ^ Kasimis BS, Wuerker RB, Hunt JD, Kaneshiro CA, Williams JL. Relationship between changes in the histologic subtype of small cell carcinoma of the lung and the response to chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol 1986;9:318–24.

- ^ Radice PA, Matthews MJ, Ihde DC et al.. The clinical behavior of “mixed” small cell/large cell bronchogenic carcinoma compared to “pure” small cell subtypes. Cancer 1982;50:2894–2902.

- ^ Dempke WC, Suto T, Reck M. Targeted therapies for non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2010;67:257-74.

- ^ Ansari J, Palmer DH, Rea DW, Hussain SA. Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:569-75.

- ^ http://www.tarceva.com/index.jsp

- ^ http://www.iressa.com/

- ^ http://www.erbitux.com/

- ^ Yang K, Wang YJ, Chen XR, Chen HN. Effectiveness and safety of bevacizumab for unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Clin Drug Investig 2010;30:229-41.

- ^ http://www.avastin.com/avastin/patient/index.m

- ^ Joerger M, Omlin A, Cerny T, Früh M.The role of pemetrexed in advanced non small-cell lung cancer: special focus on pharmacology and mechanism of action. Curr Drug Targets 2010;11:37-47.

- ^ http://www.alimta.com/pat/index.jsp

- ^ Rossi A, Galetta D, Gridelli C. Biological prognostic and predictive factors in lung cancer. Oncology 2009;77 (Suppl 1):90-6.

- ^ Jalal S, Ansari R, Govindan R, Bhatia S, Bruetman D, Fisher W, Masters G, White A, Stover D, Yu M, Hanna N; Hoosier Oncology Group. Pemetrexed in second line and beyond small cell lung cancer: a Hoosier Oncology Group phase II study. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:93-6.

- ^ Chee CE, Jett JR, Bernath AM Jr, Foster NR, Nelson GD, Molina J, Nikcevich DA, Steen PD, Flynn PJ, Rowland KM Jr. Phase 2 trial of pemetrexed disodium and carboplatin in previously untreated extensive-stage small cell lung cancer, N0423. Cancer 2010; Mar 5. [Epub ahead of print] [abstract]

- ^ Socinski MA, Smit EF, Lorigan P, Konduri K, Reck M, Szczesna A, Blakely J, Serwatowski P, Karaseva NA, Ciuleanu T, Jassem J, Dediu M, Hong S, Visseren-Grul C, Hanauske AR, Obasaju CK, Guba SC, Thatcher N. Phase III study of pemetrexed plus carboplatin compared with etoposide plus carboplatin in chemotherapy-naive patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4787-92.

- ^ http://www.pubmed.com

- ^ a b Spiro SG, Tanner NT, Silvestri GA, Janes SM, Lim E, Vansteenkiste JF, Pirker R. Lung cancer: progress in diagnosis, staging and therapy. Respirology 2010;15:44-50.

- ^ Stahel RA. Adenocarcinoma, a molecular perspective.

- ^ Ji H, Li D, Chen L et al. The impact of human EGFR kinase domain mutations on lung tumorigenesis and in vivo sensitivity to EGFR-targeted therapies. Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 485–495.

- ^ Shigematsu H, Gazdar AF. Somatic mutations of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway in lung cancers. Int J Cancer 2006;118:257–262.

- ^ Riely GJ, Politi KA, Miller VA et al. Update on epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 7232–7241.

- ^ a b Fukui T, Tsuta K, Furuta K, Watanabe S, Asamura H, Ohe Y, Maeshima AM, Shibata T, Masuda N, Matsuno Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor mutation status and clinicopathological features of combined small cell carcinoma with adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer Sci 2007;98:1714-9.

- ^ Zakowski MF, Ladanyi M, Kris MG; Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Lung Cancer OncoGenome Group. EGFR mutations in small-cell lung cancers in patients who have never smoked. N Engl J Med 2006;355:213-5.

- ^ Okamoto I, Araki J, Suto R, Shimada M, Nakagawa K, Fukuoka M. EGFR mutation in gefitinib-responsive small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1028-9.

- ^ De Oliveira Duarte Achcar R, Nikiforova MN, Yousem SA. Micropapillary lung adenocarcinoma: EGFR, K-ras, and BRAF mutational profile. Am J Clin Pathol 2009;131:694-700.

- ^ a b Motoi N, Szoke J, Riely GJ, Seshan VE, Kris MG, Rusch VW, Gerald WL, Travis WD. Lung adenocarcinoma: modification of the 2004 WHO mixed subtype to include the major histologic subtype suggests correlations between papillary and micropapillary adenocarcinoma subtypes, EGFR mutations and gene expression analysis. Am J Surg Pathol 2008;32:810-27.

- ^ Zakowski MF, Hussain S, Pao W, Ladanyi M, Ginsberg MS, Heelan R, Miller VA, Rusch VW, Kris MG. Morphologic features of adenocarcinoma of the lung predictive of response to the epidermal growth factor receptor kinase inhibitors erlotinib and gefitinib. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2009;133:470-7.

- ^ a b Horn L, Dahlberg SE, Sandler AB, Dowlati A, Moore DF, Murren JR, Schiller JH. Phase II study of cisplatin plus etoposide and bevacizumab for previously untreated, extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3501. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6006-11.

- ^ Spigel DR, Greco FA, Zubkus JD, Murphy PB, Saez RA, Farley C, Yardley DA, Burris HA 3rd, Hainsworth JD. Phase II trial of irinotecan, carboplatin, and bevacizumab in the treatment of patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:1555-60.

- ^ Zinner RG, Novello S, Peng G, Herbst R, Obasaju C, Scagliotti G. Comparison of patient outcomes according to histology among pemetrexed-treated patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer in two phase II trials. Clin Lung Cancer 2010;11:126-31.

- ^ Sica G, Wagner PL, Altorki N, Port J, Lee PC, Vazquez MF, Saqi A. Immunohistochemical expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors in primary pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2008;132:1889-95.

- ^ Sehested M, Hirsch FR, Osterlind K, Olsen JE. Morphologic variations of small cell lung cancer. A histopathologic study of pretreatment and posttreatment specimens in 104 patients. Cancer 1986;57:804-7.

- ^ Hirsch FR, Osterlind K, Hansen HH. The prognostic significance of histopathologic subtyping of small-cell carcinoma of the lung according to the classification of the World Health Organization. A study of 375 consecutive patients. Cancer 1983;52:2144–50.

- ^ Choi H, Byhardt RW, Clowry LJ, Almagro UA, Remeniuk E, Holoye PY, Cox JD. The prognostic significance of histologic subtyping in small cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Clin Oncol. 1984;7:389-97.

- ^ a b Jänne PA, Freidlin B, Saxman S, et al.: Twenty-five years of clinical research for patients with limited-stage small cell lung carcinoma in North America. Cancer 2002;95:1528-38.

- ^ Videtic GMM, Troung PT, Ash RB, Yu EW, Kocha WI, vincent MD, Torniak AT, Dar AR, Whiston F, Stitt LW. Does sex influence the impact that smoking, treatment interruption and impaired pulmonary function have on outcomes in limited stage small cell lung cancer treatment? Can Resp J 2005;12:245-50.

External links

- Lung Cancer Home Page. The National Cancer Institute site containing further reading and resources about lung cancer.

- [1]. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Lung and Pleural Tumours. 4th Edition.

Tumors: Mediastinal tumors/Thoracic neoplasm/respiratory neoplasia (C30–C34/D14, 160–163/212.0–212.4) Upper RT Lower RT Tracheal tumorSquamous cell carcinoma · Adenocarcinoma of the lung · Large-cell lung carcinoma · Rhabdoid carcinoma · Sarcomatoid carcinoma · Carcinoid · Salivary gland-like carcinoma of the lung · Adenosquamous carcinoma · Papillary adenocarcinomaCombined small-cell carcinomaNon-carcinomaBy locationPleura Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.