- Christina, Queen of Sweden

-

For other Swedish royalty named Christina, see Christina of Sweden (disambiguation).

Christina

Christina by Sébastien Bourdon Queen regnant of Sweden Reign 6 November 1632 – 6 June 1654 (21 years, 212 days) Coronation 20 October 1650 Predecessor Gustav II Adolf Successor Charles X Gustav House House of Vasa Father Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden Mother Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg Born 19 December [O.S. 8 December] 1626

StockholmDied 19 April 1689 (aged 62)

RomeBurial 22 June 1689

St. Peter's Basilica, Vatican CityReligion Roman Catholic

prev LutheranChristina (Swedish: Kristina Augusta; 18 December [O.S. 8 December] 1626 – 19 April 1689), later known as Christina Alexandra,[1] was Queen regnant of Swedes, Goths and Vandals,[2] Grand Princess of Finland, and Duchess of Ingria, Estonia, Livonia and Karelia, from 1633 to 1654.[3] She was the only surviving legitimate child of King Gustav II Adolph and his wife Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg. As the heiress presumptive, at the age of six she succeeded her father on the throne of Sweden upon his death at the Battle of Lützen. Being the daughter of a Protestant champion in the Thirty Years' War, she caused a scandal when she abdicated her throne and converted to Catholicism in 1654. She spent her later years in Rome, becoming a leader of the theatrical and musical life there. As a queen without a country, she protected many artists and projects. She is one of the few women buried in the Vatican grotto.

Christina was moody, intelligent, and interested in books and manuscripts, religion, alchemy and science. She wanted Stockholm to become the Athens of the North. Influenced by the Counter Reformation, she was increasingly attracted to the Baroque and Mediterranean culture that took her away from her Protestant country. Her unconventional lifestyle and masculine behaviour would feature in countless novels and plays, and in opera and film. In the twentieth century, Christina became a symbol of cross-dressing, transsexuality and lesbianism.

Contents

Early life

Tre Kronor in Stockholm by Govert Dircksz Camphuysen. Most of Sweden's national library and royal archives were destroyed when the castle burned in 1697

Tre Kronor in Stockholm by Govert Dircksz Camphuysen. Most of Sweden's national library and royal archives were destroyed when the castle burned in 1697

Christina was born in Tre Kronor, and her birth occurred during a rare astrological conjunction that fueled great speculation on what influence the child, fervently hoped to be a boy, would later have on the world stage.[4] The king had already sired two daughters – a nameless princess born in 1620 and then the first princess Christina, who was born in 1623 and died the following year.[5] So great expectations arose at Maria Eleonora's third pregnancy in 1626, and the castle filled with shouts of joy when she delivered a baby, which was first taken for a boy while it was hairy and screamed with a strong, hoarse voice.[6] She wrote in her autobiography, "Deep embarrassment spread among the women when they discovered their mistake." The king was very happy, stating that "She'll be clever, she has made fools of us all!"[7] Her mother remained aloof in her disappointment at the child being a girl. Christina herself believed a wetnurse had carelessly dropped her to the floor when she was a baby. A shoulder bone broke, leaving one shoulder higher than the other for the rest of her life.[8][9]

Before Gustav Adolf left for Germany to defend Protestantism in the Thirty Years' war, he secured his daughter's right to inherit the throne, in case he never returned and gave orders that Christina should be brought up as a prince.[10] Her mother, a Hohenzollern, was a woman of quite distraught temperament, melancholic, but most probably insane. After the king had died on 6 November 1632 on the battlefield, she had fetched her husband home in a coffin, with his heart separated in a box. Maria Eleonora ordered that the king should not be buried until she could be buried with him.[11] She also demanded that the coffin be kept open, and went to see it every forenoon, patting it, taking no notice of the putrefaction. Eventually the embarrassed Chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna, saw no other solution than having a guard posted at the room to prevent further episodes.[12]

Christina now became the belated centre of her mother's attention. From showing her daughter complete indifference, Maria Eleonora suddenly became perversely attentive to her. Gustav Adolf had sensibly decided that his daughter, in case of his death, should be cared for by his halfsister, Catherine of Sweden. [13] This solution did not suit Maria Eleonora, who had her sister-in-law banned from the castle. In 1636 Chancellor Oxenstierna saw no other solution to this than exiling the widow to Gripsholm castle, while the governing regency council would decide when she was allowed to meet her nine-year-old daughter.[14] This resulted in three good years, with Christina thriving in the company of her aunt Catharina and her family.

Her halfbrother Gustav Gustavson, who had Margareta Slots as mother

Her halfbrother Gustav Gustavson, who had Margareta Slots as mother

On 15 March 1633 Christina became queen at the age of six, giving rise to the nickname the "Girl King". Christina was educated as a state-child. The theologist Johannes Matthiae Gothus became her tutor; he gave her lessons in religion, philosophy, Greek and Latin. Chancellor Oxenstierna taught her politics and discussed Tacitus with her. Christina seemed happy to study ten hours a day. She learned Swedish as well as German, Dutch, Danish, French and Italian; her talent for languages was nothing short of unique.[15] Oxenstierna wrote proudly of the 14-year-old girl that "She is not at all like a female" and that, on the contrary, she had "a bright intelligence". From 1638 Oxenstierna employed a French ballet troupe under Antoine de Beaulieu, who also had to teach Christina to move around more elegantly.[16][17]

Queen regnant

The Crown of Sweden was hereditary in the family of Vasa, and from Charles IX's time excluding those Vasa princes who had been traitors or were descended from deposed monarchs. Gustav Adolf's younger brother had died years earlier, and therefore there were only females left. Despite the fact that there were living female lines descended from elder sons of Gustav I Vasa, Christina was the heiress presumptive. Although she is often called "queen", her father brought her up as a prince and her official title was King.

In 1636-1637 Peter Minuit and Samuel Blommaert negotiated with the government about the founding of New Sweden, the first Swedish colony in the New World. In 1638 Minuit erected Fort Christina in Wilmington, Delaware; also Christina River was named after her. In December 1643 Swedish troops overran Holstein and Jutland in the Torstenson War.

The National Council suggested that Christina join the government when she was sixteen; but she asked to wait until she had turned eighteen, as her father had waited until then. In 1644 she took the throne, although the crowning was postponed because of the war with Denmark. Her first major assignment was to conclude peace with that country. She did so successfully; Denmark handed over the isles of Gotland and Ösel to Sweden, whereas Norway lost the districts of Jämtland and Härjedalen, which to this day have remained Swedish.

Chancellor Oxenstierna soon discovered that Christina held differing political views from his own. In 1645 he sent his son Johan Oxenstierna to the Peace Congress in Osnabrück and Münster, presenting the view that it would be in Sweden's best interest if the Thirty Years' War continued. Christina, however, wanted peace at any cost, and therefore sent her own delegate, Johan Adler Salvius. Shortly before the conclusion of the peace settlement, she admitted Salvius into the National Council, against Chancellor Oxenstierna's will and to general astonishment, as Salvius was no aristocrat; but Christina wanted opposition to the aristocracy present. In 1648 Christine obtained a seat in the Reichstag, when Bremen-Verden and Swedish Pomerania were assigned to Sweden at the Treaty of Osnabrück.

In 1649 760 paintings, 170 marble and 100 bronze statues, 33.000 coins and medaillons, 600 pieces of cristal, 300 scientific instruments, manuscripts and books, including the Sanctae Crucis laudibus by Rabanus Maurus, the Codex Argenteus and the Codex Gigas [18] were transported to Stockholm. This art from Prague Castle had belonged to Rudolf II, Holy Roman Empire, and was captured by Hans Christoff von Königsmarck during the negotiations of the Peace of Westphalia.[19]

With the help of her uncle John Casimir, Count Palatine of Kleeburg and cousins she tried to reduce the influence of Oxenstierna and declared Karl Gustav in 1649 as her successor. Christina resisted demands from the other estates (clergy, burgesses and peasants) in the Riksdag of the Estates of 1650 for the reduction of tax-exempt noble landholdings.

Visit from Descartes, scholars and musicians

Queen Christina (at the table on the leftside) in discussion with French philosopher René Descartes. (Romantisized painting from the 19th century)

Queen Christina (at the table on the leftside) in discussion with French philosopher René Descartes. (Romantisized painting from the 19th century)

In 1645 Christina invited Hugo Grotius to become her librarian, but died on his way in Rostock. She appointed Benedict (Baruch) Nehamias de Castro from Hamburg as her Physician in ordinary.[20] In 1647 Johann Freinsheim was appointed. The Semiramis from the North corresponded with Pierre Gassendi; Blaise Pascal offered her a copy of his pascaline. To catalogue her new collection she asked Heinsius and Isaac Vossius to come to Sweden. She studied Neostoicism, the Church Fathers, the Islam, and read Treatise of the Three Impostors, a work bestowing doubt on all organized religion [21] and had a firm grasp of classical history and philosophy.[22]

In 1646 Christina's good friend, ambassador Chanut, corresponded with the philosopher René Descartes, asking him a copy of his Meditations. Christina became interested enough to start correspondence with Descartes about hate and love. Although she was very busy she invited him to Sweden, Descartes arrived on 4 October 1649. He resided with Chanut, and had to wait till 18 December until he could start with his private lessons and gave her an insight into Catholicism. With Christina's strict schedule he was invited to the castle library at 5:00 AM to discuss philosophy and religion. The premises were icy, and on 1 February 1650 Descartes fell ill with pneumonia and died ten days later; Christina was distraught with guilt. She invited Claude Saumaise, Pierre Daniel Huet, Gabriel Naudé, Christian Ravis, Samuel Bochart; embraced skepticism and became indifferent to religion.

Christina was interested in theatre and ballet. She was also herself an amateur actress, and amateur theatre was very popular at court during her reign.[16][17] Plays had always interested her, especially those of Pierre Corneille. In 1647 Antonio Brunati had built a theatrical setting in the palace.[23] Her court poet Georg Stiernhielm wrote her several plays in the Swedish language, such as Den fångne Cupido eller Laviancu de Diane performed at court with Christina in the main part of the goddess Diana.[16][17] She invited foreign companies to play at Bollhuset, such as an Italian Opera troupe in 1652 with Vincenzo Albrici and a Dutch theatre troupe with Ariana Nozeman and Susanna van Lee in 1653.[16][17] Among the French artists she employed at court was Anne Chabanceau de La Barre, who was made court singer.[16]

Christina decides not to marry

Ebba Sparre married in 1652 a brother of Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie

Ebba Sparre married in 1652 a brother of Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie

She knew it was expected of her to provide an heir to the Swedish throne. Her first cousin Charles was infatuated with her, and they became secretly engaged before he left in 1642 to do army service for three years in Germany. Christina reveals in her autobiography that she felt "an insurmountable distaste for marriage"; likewise "an insurmountable distaste for all the things that females talked about and did". She slept for 3–4 hours a night and was chiefly occupied with her studies; she forgot to comb her hair, donned her clothes in a hurry and used men's shoes for the sake of convenience; however, she was said to possess charm, and the unruly hair became her. Her best female friend and noted passion of her youth was Ebba Sparre, whom she called Belle. Most of her spare time was spent with 'la belle comtesse' - and she often called attention to her beauty. She introduced her to the English ambassador Whitelocke as her 'bed-fellow', assuring him that Sparre's intellect was as striking as her body.[24] She hosted Ebba's wedding with Jakob Kasimir De la Gardie in 1653, but the marriage would last only five years. Ebba visited her husband in Elsinore when he was shot and killed, and their three children all died when small. When Christina left Sweden she continued to write passionate love-letters to Sparre, in which she told her that she would always love her. However, Christina would also use the same emotional style when writing to women she had never met, but whose writings she admired.[25]

On 26 February 1649, Christina made public that she had decided not to marry, but wanted her first cousin Charles to be heir to the throne. The nobility objected to this, while the three other estates - clergy, burghers and peasants - accepted it. The coronation took place in October 1650. Christina went to castle of Jacobsdal, where she entered in a coronation carriage draped with black velvet embroidered in gold, and pulled by six white horses. The procession to Storkyrkan was so long that when the first carriages arrived at Storkyrkan, the last ones had not yet left Jacobsdal. All four estates were invited to dine at the castle. Fountains at the market place splashed out wine, roast was served, and illuminations sparkled. The participants were dressed up in fantastic costumes, as at a carnival.

Religion and personal views

Sébastien Bourdon, Christina of Sweden, 1653. This painting was given by Pimentel to Philip IV of Spain and is now in the Museo del Prado[26]

Sébastien Bourdon, Christina of Sweden, 1653. This painting was given by Pimentel to Philip IV of Spain and is now in the Museo del Prado[26]

Her tutor, Johannes Matthiae, stood for a gentler attitude than most Lutherans. In 1644 he suggested a new church order, but was voted down, as this was interpreted as excessively Calvinist.[citation needed] Christina, who by then had become queen, defended him against the advice of chancellor Oxenstierna, but three years later the proposal had to be withdrawn. In 1647 the clergy wanted to introduce the Book of Concord (Swedish: Konkordieboken), a book defining correct Lutheranism versus heresy, making some aspects of free theological thinking an impossibility. Matthiae was strongly opposed to this, and again was backed by Christina. The Book of Concord was not introduced.

As a young queen she felt enormous pressure, ruling the country. In August 1651, she asked the Council's permission to abdicate, but gave in to their pleas for her continuation. She had long conversations with Antonio Macedo, interpreter for Portugal's ambassador.[27] He was a Jesuit, and in August 1651 smuggled with him a letter from Christina to the Jesuit general in Rome.[28] In reply, two Jesuits came to Sweden on a secret mission in the spring of 1652, disguised as gentry and using false names. Paolo Casati had to gauge the sincerity of her intention to become Catholic. She had more conversations with them, being interested in the Catholic views on sin, immortality of the soul, rationality and free will. Though raised to follow the Lutheran Church of Sweden, around May 1652 Christina decided to become Roman Catholic. The two scholars expressed her plans to Fabio Chigi and Philip IV of Spain and the Spanish diplomat Antonio Pimentel de Prado was sent to Stockholm.[29][30]

After reigning almost twenty years, working at least ten hours a day, it looks like Christina had a nervous breakdown, a burn out or arrived at a decisive point of life. She suffered with high blood pressure, complained about bad eyesight, and pain in her neck. In February 1652 the French doctor Pierre Bourdelot arrived in Stockholm. Unlike most doctors of that time, he held no faith in blood-letting; instead he ordered sufficient sleep, warm baths and healthy meals, as opposed to Christina's hitherto ascetic way of life. She was only 25 and should take more pleasure in life. Bourdelot asked her to stop studying and working so hard [31] and to remove the books from her apartments. The funny Bourdelot showed her the 16 sonnets of Pietro Aretino, which he kept secretly in his luggage. For years Christina knew all the sonnets from the Ars Amatoria by head and was keen on the works by Marcus Valerius Martialis.[32] By subtle means Bourdelot undermined her principles. She now became an Epicurean.[33] Her mother and de la Gardie were very much against the activities of Bourdelot and tried to convince her to change her attitude towards him; Bourdelot returned to France in 1653.

Abdication

The Silver Throne of 1654, which Christina abdicated, is still today the formal seat of the Swedish monarch at Stockholm Palace.

The Silver Throne of 1654, which Christina abdicated, is still today the formal seat of the Swedish monarch at Stockholm Palace.

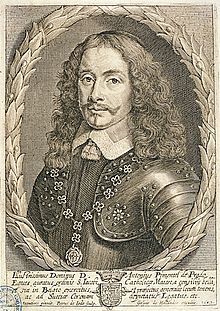

Don Antonio Pimentel de Prado (1604-1671/72) [34])

Don Antonio Pimentel de Prado (1604-1671/72) [34])

In 1651 she had told the councils she needed rest and the country a strong leader. The councils refused and Christina accepted to stay under the condition never to ask her again to marry. Within a few weeks Christina lost much of her popularity after the hanging of Arnold Johan Messenius, who had accused her of serious misbehavior and being a Jezebel. Instead of ruling she went on spending most of her time with her foreign friends in the ballroom on Sunday evenings and in the theater.

In 1653 she founded the military Amaranten order. Antonio Pimentel was appointed as its first knight; all members had to promise not to marry (again).[35] In February 1654 she plainly told the Council of her plans to abdicate. Oxenstierna replied she would regret her decision within a few months. In May they Riksdag discussed her proposals. She had asked 200.000 rikstalers a year, but received dominions instead. Financially she was secured through revenue from Norrköping town, the isles of Gotland, Öland and Ösel, estates in Mecklenburg and Pomerania. Her debts were taken over by the treasury.

So her plan to convert was not the only reason for her abdication, as there was increasing discontent with her arbitrary and wasteful ways. Within ten years, she had created 17 counts, 46 barons and 428 lesser nobles; to provide these new peers with adequate appanages, she had sold or mortgaged crown property representing an annual income of 1,200,000 riksdaler. During her ten years of reign, the number of noble families increased from 300 to about 600,[36] rewarding people, like Lennart Torstenson, and Louis De Geer for their war efforts, but also Johan Palmstruch, the banker. These donations took place with such haste that they were not always registered, and on some occasions the same piece of land was given away twice.[37]

Christina abdicated her throne on 5 June 1654 in favor of her cousin Charles Gustavus. During the abdication ceremony at Uppsala Castle, Christina wore her regalia, which were removed from her, one by one. Per Brahe, who was supposed to remove the crown, did not move, so she had to take the crown off herself. Dressed in a simple white taffeta gown she held her farewell speech with a faltering voice, thanked everyone and left the throne to Charles X, who was dressed in black. Per Brahe felt that she "stood there as pretty as an angel". Charles Gustavus, who was crowned later on that day, proposed her again to marry. Christina laughed and left the country, hoping for a warm reception in catholic countries. Charles had to move into an empty palace.

Departure and exile

In the summer of 1654, she left Sweden in man's clothes, and rode as Count Dohna, through Denmark. Relations between the two countries were still so tense that a former Swedish queen could not have traveled safely in Denmark. Christina had already packed and shipped abroad valuable books, paintings, statues and tapestries from her Stockholm castle, leaving its treasures severely depleted.[38]

Christina visited Johann Friedrich Gronovius, and Anna Maria van Schurman. In August she arrived in the Southern Netherlands, and settled down in Antwerp. For four months Christina was lodged in the mansion of a Jewish merchant. She was visited by Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria; the Prince de Condé, ambassador Chanut, as well as the former governor of Norway, Hannibal Sehested. In the afternoon she went for a ride, each evening parties were held; there was a play to watch or music to listen too. Christina ran quickly out of money and had to sell some of her tapestries, silverware and jewelry. When her financial situation did not improve the archduke invite her to his Brussels palace on Coudenberg. On 24 December 1654, she converted to the Catholic faith in archduke's chapel. Raimondo Montecuccoli and Pimentel, who had become a close friends, were present. She did not state her conversion in public, in case the Swedish council might refuse to pay her alimony. On top of this, Sweden was preparing for war against Pomerania, which meant that her income from there was considerably reduced. The pope and Philip IV of Spain could not support her openly either, as she was not publicly a Catholic yet. Christina succeeded in arranging a major loan, leaving books and statues to settle her debts.

In September she left for Italy with her entourage of 255 persons and 247 horses. The pope's messenger, the librarian Lucas Holstenius, himself a convert, waited for her in Innsbruck. On 3 November 1655, Christina converted in the Hofkirche and wrote to Pope Alexander VII and her cousin Charles X about it. To celebrate her official conversion L'Argia an opera by Antonio Cesti was performed. Ferdinand Charles, Archduke of Austria, already in financial trouble, was almost ruined by her visit. He was happy to see her leave on 8 November.

Setting off to Rome

The southbound journey through Italy was planned in detail by the Vatican and had a brilliant triumph in Ferrara, Bologna, Faenza and Rimini. In Pesaro Christina got acquainted with the handsome brothers Santinelli, who so impressed her with their poetry and adeptness of dancing that she took them into service, as well as a certain Monadeschi. On 20 December she reached the Vatican, the last distance in a sedan chair designed by Bernini. She was granted her own wing inside the Vatican, and when the pope spotted the inscription symbolizing the northern wind, Omne malum ab Aquilone (meaning "all evil comes from the North"), he ensured that it was rapidly covered with paint.

The entry into Rome proper took place on 23 December, on horseback through Porta Flaminia, which today is known as Porta del Popolo.[39] Christina met Bernini some days later, and they became lifelong friends. She often visited him at his studio, and on his deathbed he wanted her to pray for him, as she used a language that God would understand.

Celebrations for Christina of Sweden at Palazzo Barberini on 28 February 1656 when an opera by Marco Marazzoli was performed.

Celebrations for Christina of Sweden at Palazzo Barberini on 28 February 1656 when an opera by Marco Marazzoli was performed.

In St Peter's Basilica she knelt in front of the altar, and on Christmas Day she received the sacrament from the Pope himself. In his honour she took the additional names Alexandra Maria - Alexandra not only after the pope, but also in honour of her hero, Alexander the Great. Her status as the most notable convert to Catholicism of the age, and as the most famous woman at the time, made it possible for her to ignore or flout the most common requirements of obeisance to the Catholic faith. She herself remarked that her Catholic faith was not of the common order; indeed, before converting she had asked church officials how strictly she would be expected to obey the church's common observances, and received reassurances. She respected the Pope's position in the Church, but not necessarily his acts as an individual; she once commented on this to one of his servants: The papal summer residence at that time was the Quirinal Palace, located on Monte Cavallo (literally "Horse mountain"). Christina stated that Monte Cavallo might rather be named Monte degli Asini ("Donkey mountain"), as she had never met a pope with common sense during her 30 years in Rome.[40] Christina's visit to Rome was the triumph of Pope Alexander VII and the occasion for splendid Baroque festivities. For several months she was the only preoccupation of the Pope and his court. The nobles vied for her attention and treated her to a never-ending round of fireworks, jousts, fake duels, acrobatics, and operas. At the Palazzo Barberini, where she was welcomed by a crowd of 6,000 spectators, she watched in amazement at the procession of camels and elephants in Oriental garb, bearing towers on their backs.

Palazzo Farnese

Christina settled down in the Palazzo Farnese, which belonged to the Duke of Parma,[41] just opposite the church of Saint Birgitta, another Swedish woman who had made Rome her home. Christina opened an academy in the palace on 24 January 1656, called Arcadia, where the participants enjoyed music, theatre, literature and languages. Every Wednesday she held the palace open to visitors from the higher classes who could enjoy all its works of art. Belonging to the Arcadia-circle was also Francesco Negri, a Franciscan from Ravenna who is regarded as the first tourist of North Cape, Norway. Negri wrote eight letters about his walk through Scandinavia all the way up to "Capo Nord" in 1664. Another Franciscan was the Swede Lars Skytte, who, under the name pater Laurentius, served as Christina's confessor for eight years. He too had been a pupil of Johannes Matthiae, and his uncle had been Gustav Adolf's teacher. As a diplomat in Portugal he had converted, and asked for a transfer to Rome when he learnt of Christina's arrival.

However the arranged appanage from Sweden did not materialize; Christina lived off loans and donations. Her servants burned the wood from the doors to heat the premises; and the Santinelli brothers sold off works of art that came with the palace. The damage was explained away with the staff not being paid.[25]

29-year-old Christina gave occasion to much gossip when socializing freely with men her own age. One of them was Cardinal Decio Azzolino, who had been a secretary to the ambassador in Spain, and responsible for the Vatican's correspondence with European courts. He was also the leader of the Squadrone Volante, the free thinking "Flying Squad" movement within the Catholic Church. Christina and Azzolino were so close that the pope asked him to shorten his visits to her palace; but they remained lifelong friends. In a letter to Azzolino Christina writes in French that she would never offend God or give Azzolino reason to take offence, but this "does not prevent me from loving you until death, and since piety relieves you from being my lover, then I relieve you from being my servant, for I shall live and die as your slave." His replies were more reserved. Christina wrote him many letters during her travels; about 50 of these have survived.[citation needed] They were written in a code that was decrypted by Carl Bildt, ambassador of Norway and Sweden in Rome around 1900.[citation needed]

At times, things got a bit out of hand. On one occasion the couple had arranged to meet at the Villa Medici near Monte Pincio, but the cardinal did not show up. Christina hurried over to Castel Sant'Angelo, firing one of the cannons. The mark in the bronze gate in front of Villa Medici is still visible.[42]

Having run out of money and surfeited with an excess of pageantry, Christina resolved, in the space of two years, to visit France. Here she was treated with respect by Louis XIV, but the ladies were shocked by her masculine appearance and demeanour and the unguarded freedom of her conversation.

When visiting the ballet with la Grande Mademoiselle, she, as the latter recalls, "surprised me very much - applauding the parts which pleased her, taking God to witness, throwing herself back in her chair, crossing her legs, resting them on the arms of her chair, and assuming other postures, such as I had never seen taken but by Travelin and Jodelet, two famous buffoons... She was in all respects a most extraordinary creature".[43]

The Monaldeschi murder

When Christina was in Paris she influenced the dressing style by wearing a man's hat with feathers. Painting of Leonora Christina Ulfeldt

When Christina was in Paris she influenced the dressing style by wearing a man's hat with feathers. Painting of Leonora Christina Ulfeldt

The King of Spain at that time ruled Milan, and the kingdom of Naples and Sicily. The French politician Mazarin, an Italian himself, had attempted to liberate Naples from the Spanish rule against which the locals had fought, but an expedition in 1654 had failed in this. Mazarin was now considering Christina as a possible queen for Naples. The locals wanted no Italian duke on the throne; they would prefer a French prince. In the summer of 1656 Christina set sail for Marseille and from there travelled to Paris to discuss the matter. Officially it was said that she was negotiating her alimony arrangement with the Swedish king.

On 22 September 1656, the arrangement between her and Louis XIV was ready. He would recommend Christina as queen to the Neapolitans, and serve as guarantee against Spanish aggression. On the following day she left for Pesaro (?), where she settled down while waiting for the outcome of this. As Queen of Naples she would be financially independent of the Swedish king, and also capable of negotiating peace between France and Spain.[44] In the summer of 1657 she herself returned to France, officially to visit the papal city of Avignon. In October, apartments were assigned to her at Fontainebleau, where she committed an action which has indelibly stained her memory - the execution of marchese Gian Rinaldo Monaldeschi, her master of the horse.[45] Christina herself wrote her version of the story for circulation in Europe.

For two months, she had suspected Monaldeschi of disloyalty and secretly seized his correspondence, which revealed that he had betrayed her interests and put the blame on an absent member of court. Now she summoned Monaldeschi into a gallery at the palace, discussing the matter with him. He insisted that betrayal should be punished with death. She held the proof of his betrayal in her hand and so insisted that he had pronounced his own death sentence. Le Bel, a priest who stayed at the castle, was to receive his confession in the Galerie des Cerfs. He entreated for mercy, but was stabbed by two of her domestics - notably Ludovico Santinelli - in an apartment adjoining that in which she herself was. Wearing a coat of mail which is now on exhibition outside the gallery, he was chased around the room for hours before they succeeded in dealing him a fatal stab wound. Father Le Bel, who had begged on his knees that they spare the man, was told to have him buried inside the church, and Christina, seemingly unfazed, paid the abbey to hold Masses for his soul. She "was sorry that she had been forced to undertake this execution, but claimed that justice had been carried out for his crime and betrayal. She asked God to forgive him," wrote Le Bel.

Mazarin advised Christina to place the blame on Santinelli and dismiss him, but she insisted that she alone was responsible for the act. She wrote to Louis XIV about the matter, and two weeks later he paid her a friendly visit at Fontainebleau without mentioning it. In Rome, people felt differently; Monaldeschi had been an Italian nobleman, murdered by a foreign barbarian with Santinelli as her executioner. The letters proving his guilt are gone; Christina left them with Le Bel on the day of the murder, and he confirmed that they existed.[46] She never revealed what was in the letters.

The killing of Monaldeschi was legal, since Christina had judicial rights over the members of her court, as her vindicator Gottfried Leibniz claimed. As her contemporaries saw it, Christina as queen had to emphasize right and wrong, and her sense of duty was strong. She continued to regard herself as Queen Regnant all her life. When her friend Angela Maddalena Voglia was sent to an abbey by the pope, to remove her from an affair with a cardinal at the Sacro Collegio, Angela succeeded in escaping from the monastery and went into hiding at Christina's, where she was assaulted and raped by an abbot. Understandably, Christina was most upset that this could happen to someone under her roof, and demanded to have the abbot executed, but he managed to escape.[47] While still in France, she would gladly have visited England, but she received no encouragement from Cromwell. She returned to Rome and resumed her amusements in the arts and sciences.

Back to Rome

On 15 May 1658, Christina arrived in Rome for the second time, but this time it was definitely no triumph. Her popularity was lost with her execution of Monaldeschi. Alexander VII remained in his summer residence and wanted no further visits from this woman he now referred to as a barbarian. She stayed at the Palazzo Rospigliosi, which belonged to Mazarin, situated close to the Quirinal Palace; so the pope was enormously relieved when in July 1659 she moved to Trastevere to live in Palazzo Riario, on top of the Janiculus, designed by Bramante. It was Cardinal Azzolino who signed the contract, as well as provided her with new servants to replace Francesco Santinelli, who had been Monaldeschi's executioner.[48]

The Riario Palace became her home for the rest of her life. She decorated the walls with paintings, mainly from the Renaissance; and almost no paintings from northern European painters, except Holbein. No Roman collection of art could match hers. There were portraits of her friends Azzolino, Bernini, Ebba Sparre, Descartes, ambassador Chanut and doctor Bourdelot. Azzolino ensured that she was reconciled with the pope, and that the latter granted her a pension.

Revisiting Sweden

Charles at the age of five, dressed as a Roman emperor. Painting by Ehrenstrahl

Charles at the age of five, dressed as a Roman emperor. Painting by Ehrenstrahl

In April 1660 Christina was informed that Charles X had died in February. His son, Charles XI, was only five years old. That summer she went to Sweden, pointing out that she had left the throne to her first cousin and his descendant, so if Charles XI died, she would take over the throne again. But as a Catholic she could not do that, and the clergy refused to let her hold Catholic Masses where she stayed. After some weeks in Stockholm she found lodgings in Norrköping town, which was her area. Eventually she submitted to a second renunciation of the throne, spending a year in Hamburg to get her finances in order on her way back to Rome. She left her income to the bankier Diego Texeira - his real, Jewish name being Abraham - in return for him sending her a monthly allowance and covering her debts in Antwerp. She visited the Texeira family in their home and entertained them in her own lodgings, which at that time was unusual in relation to Jews.

In the summer of 1662, she arrived in Rome for the third time, followed by some fairly happy years. Some differences with the Pope made her resolve in 1667 once more to return to Sweden; but the conditions attached by the senate to her resuming residence there were now so mortifying that she proceeded no farther than Hamburg. There she was informed that Alexander VII had died. The new pope, Clement IX, had been a regular guest at her palace. In her delight at his election she threw a brilliant party at her lodgings in Hamburg, with illuminations and wine in the fountain outside. However, she had forgotten that this was a Protestant land, so the party ended with her escaping through a hidden door, threatened by stone throwing and torches. The Texeira family had to cover the repairs.[25]

Home to Rome and death

Tor di Nona to the right along the Tiber 1823

Tor di Nona to the right along the Tiber 1823

Christina's fourth and last entry in Rome took place on 22 November 1668. As in 1655 she rode through Porta del Popolo in triumph. Clement IX often visited her; they had a shared interest in plays. When the pope suffered a stroke, she was among the few he wanted to see at his deathbed. In 1671 Christina established Rome's first public theatre in a former jail, Tor di Nona.[49] The new pope, Clement X, worried about the influence of theatre on public morals. When Innocent XI became pope, things turned even worse; he made Christina's theatre into a storeroom for grain, although he had been a frequent guest in her royal box with the other cardinals. He forbade women to perform with song or acting, and the wearing of decolleté dresses. Christina considered this sheer nonsense, and let women perform in her palace.[50]

She wrote an unfinished autobiography, essays on her heroes Alexander the Great, Cyrus the Great and Julius Cæsar, on art and music (“Pensées, L’Ouvrage du Loisir” and “Les Sentiments Héroïques”) [22] and acted as patron to musicians. Carlo Ambrogio Lonati and Giacomo Carissimi were Kapellmeister; Lelio Colista luteplayer; Loreto Vittori and Marco Marazzoli singers and Sebastiano Baldini librettist.[51][52] She had Alessandro Stradella and Bernardo Pasquini to compose for her; Arcangelo Corelli dedicated his first work, Sonata da chiesa opus 1, to her [53][54] Alessandro Scarlatti directed the orchestra during a three day celebration for James II who was crowned in 1685.[55]

Her politics and rebellious spirit persisted long after her abdication of power. When Louis XIV of France revoked the Edict of Nantes, abolishing the rights of French Protestants (Huguenots), Christina wrote an indignant letter, dated 2 February 1686, directed at the French ambassador. The Sun King did not approve of this, but Christina was not to be silenced. In Rome, she made Pope Clement X prohibit the custom of chasing Jews through the streets during the carnival. On 15 August 1686, she issued a declaration that Roman Jews were under her protection, signed la Regina - the queen.

Christina remained very tolerant towards the beliefs of others all her life. She on her part felt more attracted to the Spanish priest Miguel Molinos, who had been persecuted by the Holy Inquisition over his teachings, which were inspired by the mystic Teresa of Avila and Ignace de Loyola. In February 1689, the 62-year-old Christina fell seriously ill, after a visit to the temples in Campania, receiving the last rites. She seemed to recover, but in the middle of April she had erysipelas, got pneumonia and a high fever. On her deathbed she sent the pope a message asking if he could forgive her insults - which he could. Cardinal Azzolino stayed at her side until she died on 19 April 1689.

Burial

Queen Christina's monument in St. Peter's Basilica

Queen Christina's monument in St. Peter's Basilica

Christina had asked for a simple burial, but the pope insisted on her being displayed on a lit de parade for four days in the Riario Palace. She was embalmed, covered with white brocade, a silver mask, a gilt crown and scepter. Her body was placed in three coffins - one of cypress, one of lead and finally one made of oak. The funeral procession led from Santa Maria in Valicella to St. Peter's Basilica, where she was buried within the Grotte Vaticane - only one of three women ever given this honour. Her intestines were placed in a high urn. Today, her marble sapcophagus is positioned next to that of Pope John Paul II.

In 1702 Clement XI commissioned a monument for the queen, in whose conversion he vainly foresaw a return of her country to the Faith and to whose contribution towards the culture of the city he looked back with gratitude. This monument was placed in the body of the basilica and directed by the artist Carlo Fontana. Christina was portrayed on a gilt and bronze medallion, supported by a crowned skull. Three reliefs below represented her relinquishment of the Swedish throne and abjugation of Protestantism at Innsbruck, the scorn of the nobility, and faith triumphing over heresy. It is an unromantic likeness, for she is given a double chin and a prominent nose with flaring nostrils.

Christina had named Azzolino her sole heir to make sure her debts were settled, but he was too ill and worn out even to join her funeral, and died in June the same year. His nephew, Pompeo Azzolino, was his sole heir, and he rapidly sold off Christina's art collections. Venus mourns Adonis by Paolo Veronese, for example, which was war booty from Prague, was sold by Azzolino's nephew and eventually ended up in Stockholm's National Museum. Her large and important library, originally amassed as war booty by her father Gustav Adolf from throughout his European campaign, was bought by Alexander VIII for the Vatican library, while most of the paintings ended up in France,[25] as the core of the Orleans Collection - many remain together in the National Gallery of Scotland. Her collection amounted to approximately 300 paintings. Titian's Venus Anadyomene was among them. At first, removing them from Sweden was seen as a great loss to the country; but in 1697 Stockholm castle burned down, where they would have been destroyed.

Appearance, body, and comportment

Queen Christina of Sweden by Wenceslas Hollar

Queen Christina of Sweden by Wenceslas Hollar

Christina was unusual in her own time for choosing masculine dress, and she also had some masculine physical features. Whether she chose her attire because of a self-perception as masculine, or purely for reasons of functional convenience, is difficult to know.

Based on historical accounts of Christina's physicality, some scholars[who?] believe her to have been an intersexed individual (someone with a blend of female and male genitals, hormones, or chromosomes). According to Christina's autobiography, the midwives at her birth first believed her to be a boy because she was "completely hairy and had a coarse and strong voice." After changing their minds, deciding that she was female, her father Gustav II Adolph decided "to find out for himself the nature of the matter." Such ambiguity did not end with birth, as Christina made cryptic statements about her "constitution" and body throughout life. Her unusual body was also noted by many others, who noted that the queen had a masculine voice, appearance, and movements. Although not direct evidence of her bodily makeup, Christina had a disdain for marriage, sex, female conversation and childrearing that may have stemmed from the realities of such things for a person of unusual physicality. In 1965 all of these observations led to an investigation of Christina's mortal remains, which had inconclusive results. As the physical anthropologist who undertook the investigation, Carl-Herman Hjortsjö, explained, "Our imperfect knowledge concerning the effect of intersexuality on the skeletal formation ... makes it impossible to decide which positive skeletal findings should be demanded upon which to base the diagnosis of intersexuality." Nevertheless, Hjortsjö speculated that Christina had reasonably typical female genitalia because it is recorded that she menstruated.[56]

Christina sat, talked, walked and moved in a manner her contemporaries described as masculine. She preferred men's company to women's unless the women were very beautiful, in which case she courted them. Likewise she enjoyed the company of other educated women, regardless of their looks. Throughout her later years, living in Rome, she formed a close relationship with Cardinal Azzolino, which was also controversial[citation needed] and symbolic[original research?] of her attraction to relationships which were not typical for a woman of her era and station.

Legacy

Modern bust of Christina at Halmstad

The first Swedish settlement in North America was called Fort Christina (near the present downtown Wilmington, Delaware). The nearby Christina River still bears the Queen's name.

The complex character of Christina has inspired numerous plays, books, and operatic works. August Strindberg's 1901 play Kristina depicts her as a protean, impulsive creature. "Each one gets the Christina he deserves," she remarks.[citation needed] The Finnish author Zacharias Topelius' historical allegory Stjärnormas Kungabarn also portrays her, like her father, as having a mercurial temperament, quick to anger, quicker to forgive. Kaari Utrio has also portrayed her tormented passions and thirst for love.

Christina's life was famously fictionalised in the classic feature film Queen Christina from 1933 starring Greta Garbo. This film, while entertaining, depicted a heroine whose life diverged considerably from that of the real Christina. Another feature film, The Abdication, starred the Norwegian actress Liv Ullmann, was based on a play by Ruth Wolff.

Christina has become an icon for the lesbian and feminist communities (and inspired comedian Jade Esteban Estrada to portray her in the solo musical ICONS: The Lesbian and Gay History of the World Vol. 2). Her cross-dressing has also made her a posthumous icon of the modern transgendered community.[citation needed] Finnish author Laura Ruohonen wrote a play about her called "Queen C", which presents a woman centuries ahead of her time who lives by her own rules. Raised as a boy and known by the nickname "Girl King", she vexes her contemporaries with unconventional opinions about sexuality and human identity, and ultimately abdicates the throne. First performed at the Finnish National Theatre in 2002, the play has since been translated into nine languages and staged internationally.[citation needed] The play has been performed at the Royal National Theatre in Sweden, as well as in Australia, the Czech Republic, the Netherlands, Germany and the USA, and as a stage reading in many other countries.[citation needed]

Ancestors

Christina's ancestors in three generations

Gustav I of Sweden (Vasa) Charles IX of Sweden (Vasa) Margaret Leijonhufvud Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (Vasa) Adolf, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp Christina of Holstein-Gottorp Christine of Hesse Christina of Sweden (Vasa) Joachim Frederick, Elector of Brandenburg John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg Catherine, Princess of Brandenburg-Küstrin Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg Albert Frederick, Duke of Prussia Anna, Duchess of Prussia Marie Eleonore of Cleves See also

References

- ^ Alexandra was a confirmation name, chosen in honour of the reigning pope, Alexander VII and one of her heroes Alexander the Great. He had urged her to also add "Maria" in honour of the Virgin Mary, but she did not want it, and signed her name only "Christina Alexandra", although Catholic chroniclers have assigned "Maria" to her - Buckley, p.250.

- ^ Der König der Schweden, Goten und Vandalen. Königstitulatur und Vandalenrezeption im frühneuzeitlichen Schwedenby Stefan Donecker. For more information see Dominions of Sweden and Johannes Magnus.

- ^ Sven Stolpe Drottning Kristina efter tronavsägelsen ISBN 91-0-039241-3 pp. 142 & 145

- ^ Sweden.se

- ^ Both were buried in Riddarholmskyrkan in Stockholm.

- ^ http://www.jstor.org/pss/3566533

- ^ Elisabeth Aasen: Barokke damer, edited by Pax, Oslo 2003, ISBN 82-530-2817-2

- ^ http://royalwomen.tripod.com/id4.html

- ^ B. Guilliet and others suggest it had to do with her supposed intersexuality.

- ^

"Christina Alexandra". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Christina Alexandra". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - ^ He was not buried until 22 June 1634, more than 18 months later.

- ^ Peter Englund: Sølvmasken (s. 159), edited by Spartacus, Oslo 2009, ISBN 978-82-430-0466-5

- ^ She was married to John Casimir, Count Palatine of Kleeburg, and moved home to Sweden after the outbreak of the Thirty Years' war. Their children were Maria Eufrosyne, who later married one of Christina's close friends Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie, and Karl Gustav, who inherited the throne after Christina.

- ^ http://www.windweaver.com/christina/people.htm#Maria

- ^ Letters still exist, written by her in German to her father when she was five. When the ambassador of France, Pierre Hector Chanut, arrived in Stockholm in 1645, he stated admiringly, "She talks French as if she was born in the Louvre!" (In fact it seems she spoke a sort of Liège dialect.)

- ^ a b c d e Leif Jonsson, Ann-Marie Nilsson & Greger Andersson: Musiken i Sverige. Från forntiden till stormaktstidens slut 1720 (Enligsh: "Music in Sweden. From Antiquity to the end of the Great power era 1720") (Swedish)

- ^ a b c d Lars Löfgren: Svensk teater (English: "Swedish Theatre") (Swedish)

- ^ http://www.kb.se/codex-gigas/eng/

- ^ Trevor Roper, HR (1970) Plunder of the arts in the XVIIth century, p. ?

- ^ Kruse, Sabine (1992). "Rodrigo de Castro (um 1585-1640)". In Sabine Kruse and Bernt Engelmann. Mein Vater war portugiesischer Jude …: Die sefardische Einwanderung nach Norddeutschland um 1600 und ihre Auswirkungen auf unsere Kultur. Göttingen: Steidl. pp. 73ff..

- ^ Peter Englund: Sølvmasken (p. 27)

- ^ a b Modern women philosophers, 1600-1900 By Mary Ellen Waithe [1]

- ^ A history of Scandinavian Theatre by Frederick J. Marker, Lise-Lone Marker [2]

- ^ Buckley, Veronica (2004). Christina, Queen of Sweden: The Restless Life of a European Eccentric. London.

- ^ a b c d Elisabeth Aasen: Barokke damer

- ^ Konsthistorisk tidskrift/Journal of Art History Volume 58, Issue 3, 1989

- ^ Converts, Conversion, and the Confessionalization Thesis, Once Again

- ^ It cannot have been Francesco Piccolomini who had died in June, but it was Goswin Nickel.

- ^ Garstein, O. (1992) Rome and the Counter-Reformation in Scandinavia: The age of Gustavus Adolphus and Queen Christina of Sweden (1662-1656). Studies in history of Christian thought. Leiden. [3]

- ^ The ecclesiastical and political history of the popes of Rome ..., Volume 3 By Leopold von Ranke [4]

- ^ Lanoye, D. (2001) Christina van Zweden : Koningin op het schaakbord Europa 1626 - 1689, p. 24.

- ^ Quilliet, B. (1987) Christina van Zweden : een uitzonderlijke vorst, p. 79-80.

- ^ http://www.freefictionbooks.org/books/f/2947-famous-affinities-of-history-%C3%A2%E2%82%AC%E2%80%9D-volume-1-by-orr?start=32

- ^ http://www.tercios.org/personajes/pimentel_prado.html

- ^ Memoirs of Christina, Queen of Sweden: In 2 volumes Door Henry Woodhead [5]

- ^ Peter Englund: Sølvmasken (p. 61)

- ^ Peter Englund: Sølvmasken (p. 64)

- ^ Ragnar Sjöberg in Drottning Christina och hennes samtid, Lars Hökerbergs förlag, Stockholm, 1925, page 216

- ^ Bernini had decorated the gate with Christina's coat of arms (an ear of corn) beneath that of Pope Alexander (six mountains with a star above). Also today one can read the inscription Felici Faustoq Ingressui Anno Dom MDCLV ("to a happy and blessed entry in the year 1655").

- ^ Åmodt, Ola (2007). Roma - legender og merkverdigheter. Oslo: Fritt forlag. ISBN 978-8281790124.

- ^ Quite a remarkable turn of events considering the Farnese had been in open conflict with the Papacy only 7 years earlier at the conclusion of the Wars of Castro. Now the Church's honoured guest was a guest of the family against which the Church had fought.

- ^ Ola Åmodt: Roma - legender og merkverdigheter

- ^ Memoirs of Mademoiselle de Montpensier. H. Colburn, 1848. Page 48.

- ^ Mazarin however found another arrangement to ensure peace; he strengthened this with a marriage arrangement between Louis XIV and his first cousin, Maria Theresa of Spain - the wedding took place in 1660. But this was unknown to Christina, who sent different messengers to Mazarin to remind him of their plan.

- ^ Queen Christina of Sweden and the Marquis Monaldeschi

- ^ The story is told a little different here

- ^ Ola Åmodt: Rome - legender og merkverdigheter

- ^ It is not unlikely he also had stolen from Christina' for years.

- ^ Early Music History: Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Music By Iain Fenlon [6]

- ^ In her basement there was a laboratory, where she, Giuseppe Francesco Borri and Azzolino experimented with alchemy.

- ^ Katrin Losleben, Artikel „Kristina von Schweden“, in: Musikvermittlung und Genderforschung: Lexikon und multimediale Präsentationen, hg. von Beatrix Borchard, Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hamburg, 2003ff. Stand vom 15.06.2006. URL: [7]

- ^ Aspects of the secular cantata in late Baroque Italy By Michael Talbot [8]

- ^ http://wiki.ccarh.org/wiki/MuseData:_Arcangelo_Corelli

- ^ http://indianapublicmedia.org/harmonia/queen-christina-sweden/

- ^ Music in the seventeenth century by Lorenzo Bianconi

- ^ Carl-Herman Hjortsjö, "Queen Christina of Sweden: A Medical/Anthropological Investigation of Her Remains in Rome," Acta Universitatis Lundensis Secto II 1966 No. 9 Medica, Mathematica, Scientiae Rerum Naturalium, Lund 1966, C.W.K. Gleerup, Sweden, pages 1-24. Quotes are on pages 15 and 16.

Bibliography

- Åkerman, S. (1991). Queen Christina of Sweden and her circle : the transformation of a seventeenth century philosophical libertine. New York: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-09310-9.

- Buckley, Veronica (2005). Christina; Queen of Sweden. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 1-84115-736-8.

- Essen-Möller, E. (1937). Drottning Christina. En människostudieur läkaresynpunkt. Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup.

- Goldsmith, Margaret L. (1935). Christina of Sweden; a psychological biography. London: A. Barker Ltd.

- Hjortsjö, Carl-Herman (1966). The Opening of Queen Christina's Sarcophagus in Rome. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Hjortsjö, Carl-Herman (1966). Queen Christina of Sweden: A medical/anthropological investigation of her remains in Rome (Acta Universitatis Lundensis). Lund: C.W.K. Gleerup.

- Jonsson, L. Ann-Marie Nilsson & Greger Andersson: Musiken i Sverige. Från forntiden till stormaktstidens slut 1720 ("Music in Sweden. From Antiquity to the end of the Great power era 1720") (Swedish)

- Löfgren, Lars : Svensk teater (Swedish Theatre) (Swedish)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Mender, Mona (1997). Extraordinary women in support of music. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. pp. 29–35.

- Meyer, Carolyn. Kristina, the Girl King: Sweden, 1638.

- Platen, Magnus von (1966). Christina of Sweden: Documents and Studies. Stockholm: National Museum.

- Stolpe, Sven (1996). Drottning Kristina. Stockholm: Aldus/Bonnier.

- Torrione, Margarita (2011), Alejandro, genio ardiente. El manuscrito de Cristina de Suecia sobre la vida y hechos de Alejandro Magno, Madrid, Editorial Antonio Machado (212 p., color ill.) ISBN 978-84-7774-257-9.

External links

- "Queen Christina of Sweden". About: Women's History. http://womenshistory.about.com/od/rulerspre20th/p/queen_christina.htm. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- Tomb of Queen Christina in the Vatican Grottoes

- Monument to Queen Christina in St Peter's Basilica

- Coins of Sweden by David Ruckser

- [9]

ChristinaBorn: 8 December 1626 Died: 19 April 1689Regnal titles Preceded by

Gustav II AdolfQueen of Sweden

1632–1654Succeeded by

Charles X GustavNew title Duchess of Bremen and Verden

1648–1654Swedish princesses by birth The generations indicate descent form Gustav I, from the House of Vasa, and continues through the Houses of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, Holstein-Gottorp; and the Bernadotte, the adoptive heirs of the House of Holstein-Gottorp, who were adoptive heir of the Palatinate-Zweibrückens. 1st generation Catharina, Countess of Ostfriesland · Cecilia, Margravine of Baden-Rodemachern · Anna Maria, Countess Palatine of Veldenz · Sophia, Duchess of Saxe-Lauenburg · Elizabeth, Duchess of Mecklenburg-Gadebusch2nd generation Princess Isabella · Princess Sigrid · Princess Anna · Princess Margareta Elizabeth · Princess Elizabeth Sabina · Catharina, Countess Palatine of Zweibrücken · Princess Maria · Princess Christina · Princess Maria Elizabeth, Duchess of Östergötland** · Princess Christina3rd generation Princess Anna Maria^ · Princess Catharina^ · Princess Catharina^ · Princess Anna Constance^ · Princess Anna Catharina Constance, Hereditary Countess Palatine of Neuburg^ · Princess Christina · Christina · Maria Eufrosyne, Countess Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie4th generation Princess Maria Anna Isabella^ · Princess Maria Anna Theresa^5th generation 6th generation none7th generation Sophia Albertina, Princess-Abbess of Quedlinburg8th generation Princess Louisa Hedwig9th generation 10th generation 11th generation 12th generation 13th generation 14th generation 15th generation *also a princess of Sweden by marriage

^also a princess of Poland and Lithuania by birth

**also a princess of NorwayCategories:- Swedish monarchs

- Swedish queens

- Rulers of Finland

- Dukes of Bremen and Verden

- Candidates for the Polish elective throne

- House of Vasa

- Queens regnant

- Swedish Roman Catholics

- Converts to Roman Catholicism from Lutheranism

- Female rulers of Finland

- Roman Catholic monarchs

- Modern child rulers

- 1626 births

- 1689 deaths

- Aphorists

- Swedish monarchs of German descent

- Burials at St. Peter's Basilica

- 17th-century female rulers

- Monarchs who abdicated

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.