- Neath and Tennant Canal

-

Neath and Tennant Canal The exit from Clun Isaf lock, restored in 2007 Original owner Neath Canal Nav Co, Port Tennant Nav Co Principal engineer Thomas Dadford Other engineer(s) George Tennant Date of act 1791 Date of first use 1795 Date completed 1824 Date closed 1930s Date restored 1990 onwards Maximum boat length 60 ft 0 in (18.29 m) Maximum boat beam 9 ft 0 in (2.74 m) Start point Glynneath End point Briton Ferry / Swansea Docks Locks 15 (originally 21)

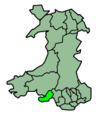

Status Under restoration Navigation authority Neath Canal Navigation Co, Port Tennant Navigation Co The Neath and Tennant Canals are two independent but linked canals in South Wales that are usually regarded as a single canal. The Neath Canal was opened from Glynneath to Melincryddan, to the south of Neath, in 1795 and extended to Giants Grave in 1799, in order to provide better shipping facilities. Several small extensions resulted in in reaching its final destination at Briton Ferry. No traffic figures are available, but it was successful, as dividends of 16 per cent were paid on the shares. The canal was 13.5 miles (21.7 km) long and included 19 locks.

The Tennant Canal was a development of the Glan-y-wern Canal, which was built across Crymlyn Bog to transport coal from a colliery on its northern edge to a creek on the River Neath called Red Jacket Pill. It closed after 20 years, but was enlarged and extended by George Tennant in 1818, to provide a navigable link from the River Neath to the River Tawe at Swansea docks. In order to increase trade, he built an extension to Aberdulais basin, where it linked to the Neath Canal. The extension was built without an act of Parliament and Tennant experienced a long delay while he attempted to resolve a dispute with a landowner over the routing of the canal. Once opened, much of the Neath traffic used the Tennant Canal, as Swansea provided better facilities for transferring cargo to ships.

Use of the canals for navigation ceased in the 1930s, but because they supplied water to local industries and to Swansea docks, they were retained as water channels. The first attempts at restoration began in 1974 with the formation of the Neath and Tennant Canals Society. The section north of Resolven was restored in the late 1980s, and the canal from Neath to Abergarwed has been restored more recently. This project involved the replacement of Ynysbwllog aqueduct, which carries the canal over the river Neath, with a new 35-yard (32 m) plate girder structure, believed to be the longest single-span aqueduct in Britain. Some obstacles remain to its complete restoration, but current thinking includes making it part of a small network by creating a link through Swansea docks to a restored Swansea Canal.

Contents

Neath Canal

Encouraged by the recent granting of an Act of Parliament to authorise the building of the Glamorganshire Canal, a meeting took place at the Ship & Castle public house in Neath on 12 July 1790, which resolved to build a canal from Pontneddfechan to Neath, and another from Neath to Giant's Grave. Among those attending was Lord Vernon, who had already built a short canal near Giant's Grave to connect the River Neath to furnaces at Penrhiwtyn. Thomas Dadford was asked to survey a course, and he was assisted in this task by his father and brother. He proposed a route which required 22 locks, part of which was a conventional canal, while other parts used the River Neath. Dadford costed the project at £25,716, but in early 1791, Lord Vernon's agent, Lewis Thomas, proposed two new cuts, and the idea of using the river was dropped soon afterwards.[1]

The canal was authorised by an Act of Parliament passed on 6 June 1791, which created The Company and Proprietors of the Neath Canal Navigation, who had powers to raise £25,000 by the issuing of shares, and an additional £10,000 if necessary. As well as building the canal, the Canal Company could build inclined planes, railways or rollers if required, and could optionally use the bed of the River Neath.[2] The canal was to run from Glynneath, (called Abernant at the time), which was not so far up the valley as Pontneddfechan, to Melincryddan Pill at Neath, where it would join the river.[3] Thomas Dadford was employed as Engineer,[4] and construction started from Neath, northwards towards Glynneath. The canal had reached the River Neath at Ynysbwllog by 1792, when Dadford resigned to take up work on the Monmouthshire Canal. He was replaced by Thomas Sheasby,[4] who failed to complete the canal by the November 1793 deadline given to him, and was arrested in 1794 for irregularities in the accounts of the Glamorganshire Canal. The canal company completed the building work by 1795, using direct labour, although the lock into the river was never built. Rebuilding of locks and other improvements continued to be made for several years afterwards.[5]

There was no immediate pressure to extend the canal to Giants Grave, as access to Neath for coastal vessels of up to 200 long tons (200 t) had been improved in 1791 by the construction of the Neath Navigable Cut.[3] However, a second Neath Canal Act was passed on 26 May 1798,[2] to authorise an extension of about 2.5 miles (4.0 km) to Giants Grave, where better facilities for transferring goods to sea-going vessels were available. Thomas Dadford again surveyed the route, but Edward Price from Gofilon acted as engineer. This part of the canal was financed by Lord Vernon, although he was also paid £600 for his Penrhiwtyn canal, which became part of the main line. The extension was completed on 29 July 1799, and terminated at a basin close to Giants Grave Pill. Flood gates on the canal enabled water to be released into the pill to scour it of silt. The total cost of the project was about £40,000, which included 19 locks and a number of access tramways.[6] Between 1815 and 1842, additional docks and wharfs were built at Giants Grave, extending the length slightly, and the canal was extended to Briton Ferry by the construction of the Jersey Canal in 1832, which was about 0.6 miles (1.0 km) long, and was built without an Act of Parliament by the Earl of Jersey. Another short extension was made around 1842.[7] The final length of the canal was 13.5 miles (21.7 km).

From the northern terminus, a tramway connected the canal to iron works at Aberdare and Hirwaun. This was built in 1803, and included an incline just north of Glynneath, which was powered by a high-pressure Trevithick steam engine.[4] The Tappenden brothers had bought into the iron industry in 1802, and built the tramway because of high tolls on the Glamorganshire Canal,[8] but by 1814 they were bankrupt, and had no further connections with the canal.[4]

Operation

Mineral resources near the top end of the canal included ironstone, which was normally extracted by scouring. This caused problems for the canal, as silt was deposited in the feeders and the top pounds. The Fox family, who were based at Neath Abbey, but who were scouring ironstone further up the valley, agreed to construct a new feeder in 1807 to mitigate the problem. Protests made to the Tappendens, who were scouring at Pen-rhiw and Cwm Gwrelych were less successful. As the pounds were silting up, the company took legal action in 1811, which found in their favour, recognising that the canal would soon be useless unless something was done.[9]

Trade steadily grew. Three small private branches were built to serve the industries of the valley. Near the top of the canal, a branch was constructed in 1800, which ran towards Maesmarchog, and was connected to collieries by nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) of tramroad. At Aberclwyd, a branch built in 1817 served the Cnel Bach limekiln which was situated on the river bank. Below Neath, a 550-yard (500 m) branch left the main line at Court Sart to connect to a tramroad serving the collieries at Eskyn. Although there are no figures for the tonnage carried, apart from a mention of 90,000 tons of coal in 1810, receipts increased from £2,117 in 1800 to £6,677 in 1830. Subscribers had paid a total of £107.50 for their shares, and dividends were paid from 1806, rising from £2.00 in 1806 to £18.00 in 1840. Based on the receipts, it has been estimated that some 200,000 tons of coal were carried when trade was at its peak, supplemented by iron, ironstone and fire clay.[10]

Facilities at Giants Grave improved, and included jetties to enable ships' ballast to be landed and dumped, rather than being thrown overboard. This latter approach had caused problems at Newport for the Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal, where ballast had been thrown into the river, and at Cardiff for the Glamorganshire Canal, where it had been thrown into the canal basin. Efforts were also made to improve the facilities at Neath. From 1818, a Harbour Board was established, and banks of copper slag, marked with buoys, were used to confine the channel. This enabled ships of over 300 tons to reach Neath quays on spring tides, although Giants Grave still had to be used on neap tides. From 1824, when the connection to the Tennant Canal opened, much of the trade crossed the river and passed down the western bank to the port of Swansea.[11]

Glan-y-wern Canal

The Glan-y-wern Canal was built to connect Richard Jenkins' colliery at Glan-y-wern with the River Neath at Trowman's Hole, an inlet across the mud flats from the main channel of the river Neath, which was later known as Red Jacket Pill. Jenkins obtained a lease to build it from Lord Vernon on 14 August 1788, but died on the same day. Edward Elton took over management of the colliery, and the canal was constructed by 1790, although there was no actual connection to the river.[12] At Red Jacket, cargos were transhipped from the small boats used on the canal to larger vessels in the pill, which was tidal. The canal remained in use for about 20 years. Elton went bankrupt and died in 1810, after which Lord Vernon, who had leased the land on which the canal was built to Elton, placed a distraint on the wharves at Red Jacket and on the barges, and it became disused.[13]

George Tennant incorporated the southern section into his Tennant Canal. The northern branch over the Crymlyn Bog was derelict by 1918.[14] It branches northwards in Crymlyn Burrows and terminates at the Crymlyn Bog nature reserve, now a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI).

The Tennant Canal

George Tennant, who had been born in 1765 and was the son of a solicitor in Lancashire, moved to the area in 1816, after he had bought the Rhydings estate. The Glan-y-wern Canal was unused at the time, following Lord Vernon's distraint, but Tennant, who had no previous experience with canals, decided to lease it, enlarge it and extend it. He planned to make it suitable for barges of 30 to 35 long tons (30 to 36 t), which would gain access to the river Neath through a lock at Red Jacket. Where the canal turned northwards across Crymlyn Bog, he would extend it to the west, to terminate at a lock into the River Tawe, near Swansea harbour. He believed that Swansea docks would provide a better shipping point than Neath or Giants Grave, and hoped that the canal would encourage the development of the corridor through which it ran. He attempted to gain support for the scheme from local landowners, but when none was forthcoming, he decided to fund the project himself. Lord Vernon's estate had been inherited by the Earl of Jersey in 1814, and so Tennant leased the Glan-y-wern Canal from him.[15]

Work started in 1817, under the direction of the engineer William Kirkhouse, and the canal was completed by the autumn of 1818, running from near the east pier on the River Tawe at Swansea to the River Neath at Red Jacket.[16] The canal was built to a grander scale than originally intended, and could be navigated by barges of 50 to 60 long tons (51 to 61 t). The main line was 4 miles (6.4 km) long, and the 1.4-mile (2.3 km) branch to Glan-y-wern was also reopened, for it supplied regular cargos of coal. Other products carried included timber, bark, fire-bricks and sand, but the volume of goods carried was insufficient to make a profit. He negotiated with the Neath Canal, who gave him permission for build a lock into the river from their canal, either at Giants Grave or Court Sart pill, but the idea of working canal boats across a tidal river was not ideal, and he did not build the lock.[17]

Instead, he decided to build an extension to link up with the Neath Canal basin at Aberdulais. Again he sought support from local landowners, including Lord Jersey, Lord Dynevor and the Duke of Beaufort, but again none was forthcoming. He decided to build it as a private canal, without an Act of Parliament, and work started in 1821. Engineering problems were experienced near Neath Abbey, where a 500-yard (460 m) cutting was required through what appeared to be quicksand. Eventually, an inverted masonry arch had to be built to contain the canal and stop the sand collapsing. The lack of an act to authorise the canal proved to be a problem in April 1821, when L. W. Dillwyn refused permission to allow Tennant to cut through his land to pass under the Swansea road.[18] In February 1822, Dillwyn obtained an injunction against Tennant, who then attempted to change Dillwyn's opinion by sending a stream of important people to argue his case. Finally, in the autumn, Tennant offered the Neath Canal terms for the use of the junction which were so favourable to them that they accepted. Dillwyn, who was a Neath Canal shareholder, was sent a conciliatory letter and eventually agreed to negotiate with Tennant, whom he described as "that terrible plague Mr. Tennant." The final section included the only lock on the main line, which was followed by a 340-foot (100 m) ten-arched aqueduct across the River Neath, and the junction with the Neath Canal. The total length of the canal, when it was opened on 13 May 1824, was 8.5 miles (13.7 km), and it had cost around £20,000, which did not include the price of the land or of the harbour at Port Tennant.[19]

At the Swansea end, Tennant built a sea-lock, so that boats could enter Fabian Bay, and named the area Port Tennant. His terminus was destroyed when the Prince of Wales Dock was constructed by the Swansea Harbour Trust in 1881. It occupied all of the area which had been Fabian Bay, and so a lock was constructed to enable boats to reach tidal water by passing through the dock, and a wharf for the canal was constructed at the eastern end of the dock. Tennant's wharf was again destroyed in 1898, when the dock was extended. Wharfage was provided for the canal along the entire southern side of the extension, but no lock was built to allow canal boats to enter the dock, even though the act of parliament made provision for one. A new branch of the canal was built in 1909, which included a lock into the newly constructed Kings Dock, where a lay-by berth was provided on its north side.[20]

Operation

Prior to its opening, Tennant has estimated that the canal would carry 99,994 tons per year, and generate £7,915 in income. Traffic built up, and by the 1830s, annual tonnage was around 90,000 tons, but revenues were less than anticipated, and produced a profit of about £2,500 per year. Initially, it was known as the Neath and Swansea Junction Canal, but by 1845 it had become known as the Tennant Canal. The water was 5 feet (1.5 m) deep between Red Jacket and Aberdulais, and 7 feet (2.1 m) deep from Red Jacket to Swansea harbour. This provided a large reservoir of water, which was used to scour the tidal basin at Port Tennant. Boats typically carried 25 tons, which allowed them to work on the Neath Canal as well. Several short branches were built, including one to the Vale of Neath Brewery which opened in 1839 and was privately funded by the brewery. In the same year, the Glan-y-wern Canal was dredged and re-opened.[21]

Goods carried were mainly coal and culm, but also included timber, iron ore, sand, slag and copper ore, with smaller amounts of foodstuffs and general merchandise. Establishment of industries at Port Tennant, which included Charles Lambert's copperworks in the 1850s and a patent fuel works in the 1860s, resulted in increased carrying of coal, both from Glan-y-wern and Tir-isaf collieries. Tir-isaf was served by a 1-mile (1.6 km) branch built in 1863 by the Earl of Jersey, but leased to the Tennants. Traffic figures reached 225,304 tons in 1866, and then gradually declined after that, but this provided a steady revenue until 1895. The river lock at Red Jacket had a chequered history. Once the line to Aberdulais basin had been opened, it was barely used, and Tennant thought about removing it in 1832. However, it was back in use some time later, and was unused again in the 1880s, only to be rebuilt in 1898.[22]

Demise

The canals faced competition from the Vale of Neath Railway after 1851, but remained profitable until the early 1880s, in the case of the Neath Canal, and the 1890s for the Tennant. An unusual aspect of the Tennant's success was that tolls were maintained, although tonnage dropped. Most canals at this time made significant cuts to tolls in an attempt to remain competitive with the railways. After 1883, the Neath Canal carried small amounts of silica and gunpowder, but traffic had virtually ceased by 1921. Navigation on the Neath Canal came to an end in 1934, and on the Tennant Canal soon afterwards. However, most of the infrastructure was maintained as the canals supplied water to local industries.[23]

When the Glynneath bypass was built in the 1970s, the canal was culverted above Ysgwrfa lock, to allow the road to be straightened, and reduced in width beyond that, to allow the road to be widended. Above Pentremalwed lock, the road was built over the canal bed, and all traces have gone. This road was superseded by the A465(T) dual carriageway when it opened in 1996, and has become the B4242.[24] The part which covered the final section of the canal is no longer a road, although the dual carriageway runs over the site of the Glynneath basin.

At Port Tennant, the course of the canal has been covered over by railways, roads and other facilities of the port, but continues to supply water to the Prince of Wales dock through a large culvert, which helps to maintain water levels in the docks.[20] The Tennant canal is still owned by the Coombe-Tennant family.[4]

Restoration

The canals are the subject of active restoration projects. Local interest resulted in the formation of the Neath and Tennant Canals Society in 1974, to promote a restoration scheme, and the following year the canal benefitted from the job creation scheme run by the Manpower Services Commission.[25] The upper section from Resolven to Ysgwrfa was restored in 1990,[26] and received a Europa Nostra award in 1988 for the quality of the work, and a Civic Trust Award in 1992. The £4 million project was jointly funded by the Welsh Office and the Prince of Wales Trust.[26] On a smaller scale, the Canals Society refurbished Rheola aqueduct in 1990, so that their trip boat, named Thomas Dadford and launched on 12 July, could make longer journeys.[27] In 1993, the section from Ynysarwed to Tyn-yr-Heol lock at Tonna was polluted by iron-bearing water discharging from a mine adit. A treatment plant and wetlands were installed to clean the water, and this £1.6 million project was commissioned in 1999.[26]

The next restoration project involved the section from Neath town centre to Abergarwed, near the Ynysarwed locks. An initial £2.7 million project enabled all of the polluted section to be cleaned, and much of the infrastructure to be restored. Nearly 65,000 tonnes of polluted material were dredged from the canal and removed.[26] An additional £1.6 million project was funded by the European Union Objective 1 project, the Welsh Assembly and Neath Port Talbot Council. This included complete replacement of the Ynysbwllog aqueduct,[26] part of which was washed away in a flood in 1979. The water flow was maintained by replacing the missing arch with pipes, but the towpath was not re-instated until over 20 years later, when a steel footbridge was built. Completed in March 2008, the new 35-yard (32 m) plate girder aqueduct is believed to be the longest single span aqueduct in the UK. It is 23 feet (7.0 m) wide, and includes a footpath on both sides of the navigation channel.[26][28]

Future Plans

Several obstacles remain to be overcome before the canal restoration can be completed. Below Resolven, a new bridge would be needed where the canal is culverted under Commercial Road, and the infilled section to Abergarwed would need to be excavated. Rebuilding of the two Ynysarwed locks and Resolven lock would then join the existing two restored sections together. Extension to the south is blocked by a bridge at water level in Neath, but Neath Port Talbot Council are investigating the possibility of replacing it with a lifting or bascule bridge. The Tennant Canal presents few problems beyond that of the aqueduct below Aberdulais basin, which is a scheduled ancient monument, and rebuilding of the lock below that. Resolution of these issues would create around 20 miles (32 km) of navigable canal.[29]

At Briton Ferry, the canal ends under the M4 motorway at a scrapyard, but there are plans to refurbish Brunel's Briton Ferry dock, just to the south, and a short extension to it would provide a good terminus. At Ysgwrfa, the final five locks have been severed by a re-alignment of the road and the construction of a culvert, but the road has carried a lot less traffic since the A465 bypass was opened, and could possibly be re-routed along its original course, where the bridge over the canal still exists. The terminus would be near the Lamb and Flag public house, below the final two locks, which are unlikely to be restored. At Swansea, the Tennant canal could be re-linked to the Prince of Wales Dock, and hence to the River Tawe, which has become a large marina since the construction of a tidal barrage. This could then provide a link to a restored Swansea Canal.[29] Associated British Ports, who run Swansea Docks, rejected the idea of a canal link in 1997,[30] but since then the Prince of Wales dock has become the subject of a regeneration scheme, and a route for the canal has been reserved in the planning document.[29]

Canals in popular culture

The opening of the Tennant Canal in 1824 inspired Elizabeth Davies, who owned a lollipop-shop in Neath, to write a 19-verse poem, which was published by Filmer Fagg of Swansea.[19] More recently, the canals have inspired local musicians to write songs about them. Huw Pudner and Bob Thomas have written a folk ballad called The Lockkeepers Daughter about the Neath canal,[31] and Pudner worked with Chris Hastings to produce a folk ballad called The Red Jacket Stream about the Tennant Canal.[32]

Points of interest

See also

Bibliography

- Cumberlidge, Jane (2009). Inland Waterways of Great Britain (8th Ed.). Imray Norie Laurie and Wilson. ISBN 978-1-84623-010-3.

- Hadfield, Charles (1967). The Canals of South Wales and the Border. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4027-1.

- Ludgate, Martin (January 2010). Restoration: Neath and Tennant Canals. Canal Boat Magazine. ISSN 1362-0312.

- Nicholson (2006). Nicholson Guides Vol 4: Four Counties and the Welsh Canals. Harper Collins Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-00-721112-0.

- Priestley, Joseph (1831). "Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals, and Railways, of Great Britain". http://www.jim-shead.com/waterways/sdoc.php?wpage=PNRC0461#PNRC461.

- Rees, D Ben (1975). Chapels in the Valley. Ffynnon Press. ISBN 978-0902158085. http://home.clara.net/tirbach/HelpPagepearlsGLA4.html#Glamorgan.

- Squires, Roger (2008). Britain's restored canals. Landmark Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84306-331-5.

- "The Neath and Tennant Canals Trust". http://www.neath-tennant-canals.org.uk/.

References

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 63–64

- ^ a b Priestley 1831, pp. 460–462

- ^ a b Hadfield 1967, p. 64

- ^ a b c d e Nicholson 2006, pp. 56–64

- ^ Hadfield 1967, p. 65

- ^ Hadfield 1967, p. 66

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 74–75

- ^ Rees 1975

- ^ Hadfield 1967, p. 70

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 70–72

- ^ Hadfield 1967, p. 72

- ^ Cumberlidge 2009, pp. 370–371

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 76–77

- ^ Hadfield 1967, p. 88

- ^ Hadfield 1967, p. 77

- ^ Neath and Tennant Canals Trust: Tennant Canal History

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 77–78

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 78–79

- ^ a b Hadfield 1967, pp. 80–81

- ^ a b "The Tennant Canal". Swansea Docks. http://www.swanseadocks.co.uk/Tennant%20Canal.htm.

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 85–86

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 86–88

- ^ Hadfield 1967, pp. 74, 87–88

- ^ "Where is Resolfen". Resolfen History Society. 13 July 2006. http://eclecs.blogspot.com/2006/07/where-is-resolfen.html.

- ^ Squires 2008, pp. 84, 88

- ^ a b c d e f "Newsletter Issue 3". Association of Inland Navigation Authorities. February 2007. p. 7. http://www.aina.org.uk/docs/feb07nl.pdf.

- ^ Squires 2008, pp. 126–127

- ^ "Ynysbwllog Aqueduct". Dawnus Construction. http://www.dawnus.co.uk/en/content/cms/Projects/Civil_Engineering/Bridges_and_Structur/Ynysbwllog_Aqueduct_/Ynysbwllog_Aqueduct_.aspx. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- ^ a b c Ludgate 2010, pp. 79–80

- ^ Squires 2008, p. 140

- ^ Waterway Songs Archive (words), accessed 2010-02-25

- ^ Waterway Songs Archive (words), accessed 2010-02-25

External links

Transport in Neath Port Talbot county borough Road M4 motorway · European route E30 · A48 road · A465 road · A474 road · A483 road · A4063 road · A4107 road · A4067 road · A4069 road · A4109 road · A4221 road · A4230 road · A4241 road

Bus First Cymru · National Express · Neath bus station · Neath railway station · Port Talbot bus stationNational Cycle Network Railway lines Railway stations Sea Canals Neath and Tennant CanalTransport in Swansea Road M4 motorway · European route E30 ·

A48 road · A483 road · A484 road · A4067 road · A4216 road · A4217 road · A4240 road · A4118 road

Bus First Cymru · Veolia Transport Cymru · Gower Explorer · Swansea Metro · National Express · Swansea bus station · Gorseinon bus stationNational Cycle Network Railway lines Railway stations Air Waterways Sea Categories:- Canals in Wales

- Transport in Swansea

- History of Swansea

- Transport in Neath Port Talbot

- Vale of Neath

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.