- Breaking wheel

-

The breaking wheel, also known as the Catherine wheel or simply the wheel, was a torture device used for capital punishment in the Middle Ages and early modern times for public execution by bludgeoning to death. It was used during the Middle Ages and was still in use into the 19th century.

Contents

Description and uses

The wheel was typically a large wooden wagon wheel with many radial spokes, but a wheel was not always used. In some cases the condemned were lashed to the wheel and beaten with a club or iron cudgel, with the gaps in the wheel allowing the cudgel to break through. Alternatively, the condemned were spreadeagled and broken on a St Andrew's cross consisting of two wooden beams nailed in an "X" shape,[1][2] after which the victim's mangled body might be displayed on the wheel.[3] During the execution for parricide of Franz Seuboldt in Nuremberg on 22 September 1589, a wheel was used as a cudgel: the executioner used wooden blocks to raise Seuboldt's limbs, then broke them by slamming a wagon wheel down onto the limb.[4]

In France, the condemned were placed on a cartwheel with their limbs stretched out along the spokes over two sturdy wooden beams. The wheel was made to revolve slowly, and a large hammer or an iron bar was then applied to the limb over the gap between the beams, breaking the bones. This process was repeated several times per limb. Sometimes it was 'mercifully' ordered that the executioner should strike the condemned on the chest and stomach, blows known as coups de grâce (French: "blows of mercy"), which caused fatal injuries. Without those, the broken man could last hours and even days, before shock and dehydration caused death. In France, a special grace, the retentum, could be granted, by which the condemned was strangled after the second or third blow, or in special cases, even before the breaking began.

In the Holy Roman Empire, the wheel was punishment reserved primarily for men convicted of aggravated murder (murder committed during another crime, or against a family member). Less severe offenders would be cudgelled 'top down', with a lethal first blow to the neck. More heinous criminals were punished 'bottom up', starting with the legs, and sometimes being beaten for hours. The number and sequence of blows was specified in the court's sentence. Corpses were left for carrion-eaters, and the criminals' heads often placed on a spike.[5]

Legend has it that St. Catherine of Alexandria was sentenced to be executed on one of these devices, which thereafter became known as the Catherine wheel, also used as an iconographic attribute. The wheel miraculously broke when she touched it; she was then beheaded.

In Scotland, a servant named Robert Weir was broken on the wheel at Edinburgh in 1603 or 1604 (sources disagree). This punishment had been used infrequently there. The crime had been the murder of John Kincaid, Lord of Warriston, on behalf of his wife. Weir was secured to a cart wheel and was struck and broken with the coulter of a plough. Lady Warriston was later beheaded.[6][7]

The breaking wheel was frequently used in the Great Northern War in the early 1700s when the Tsardom of Russia challenged the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in northern Central Europe and Eastern Europe. Russian forces used this method to execute Cossacks and during the massacres of civilians at Baturyn and Lebedyn. The Swedish king, Charles XII also ordered the Livonian nobleman Johann Patkul to be broken alive on the wheel for high treason.

This method of execution has been used in 18th-century America following slave revolts. It was once used in New York after several whites were killed during a slave rebellion in 1712. Between 1730 and 1754 prior to the Louisiana Purchase, 11 slaves in French-controlled Louisiana, who had revolted against their masters, were killed on the wheel.[8]

The breaking wheel was used in Germany as recently as the early 19th century for the crime of parricide, and the last known use occurred in 1841 when the assassin of the Bishop of Ermeland in Prussia was executed in this manner.[9]

Metaphorical uses

The execution of Peter Stumpp, involving the breaking wheel in use in Cologne in the early modern period.

The execution of Peter Stumpp, involving the breaking wheel in use in Cologne in the early modern period.

The breaking wheel was also known as a great dishonor, and appeared in several expressions as such. In Dutch, there is the expression opgroeien voor galg en rad, "to grow up for the gallows and wheel," meaning to come to no good. It is also mentioned in the Chilean expression morir en la rueda, "to die at the wheel," meaning to keep silent about something. The Dutch phrases ik ben geradbraakt, literally "I have been broken on the wheel," the German expression sich gerädert fühlen, "to feel wheeled," and the Swedish verb rådbråka (from German radbrechen), "to break on the wheel," are sometimes used and carries a meaning of mental exhaustion or trying to go through one's mind to remember. In Danish, however, the similar word "radbrækket" refers almost exclusively to physical exhaustion. In Finnish teilata, "to execute by the wheel," refers to forceful and violent critique or rejection of performance, ideas or innovations. In Norwegian, the verb radbrekke is generally applied to art and language, and refers to use thereof which is seen as despoiling tradition and courtesy, with connotations of willful ignorance and/or malice. The German verb radebrechen has acquired a somewhat different meaning, "to speak in the manner of one who has poor command of the language," i.e. haltingly, using incorrect words, with a strong foreign accent etc.

The word roué, "dissipated debauchee," is French, and its original meaning was "broken on the wheel." As execution by breaking on the wheel in France and some other countries was reserved for crimes of peculiar atrocity, roué came by a natural process to be understood to mean a man morally worse than a "gallows-bird," a criminal who only deserved hanging for common crimes. He was also a leader in wickedness, since the chief of a gang of brigands (for instance) would be broken on the wheel, while his obscure followers were merely hanged. Philip, Duke of Orléans, who was regent of France from 1715 to 1723, gave the term the sense of impious and callous debauchee, which it has borne since his time, by habitually applying it to the very bad male company who amused his privacy and his leisure. The locus classicus for the origin of this use of the epithet is in the Memoirs of Saint-Simon.

In English, the quotation "Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?" from Alexander Pope's "Epistle to Dr Arbuthnot" has entered common use as referring to putting great effort into achieving something minor or unimportant.

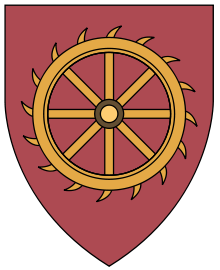

Coats of Arms with Catherine Wheels

- Altena, Germany

- Hjørring, Denmark, where Saint Catherine is the patron-saint of the Town.

- Kaarina, Finland, until 2009 and Piikkiö's union with Kaarina

- Sinaai, Belgium

- Goa, India, when it was in Portuguese possession

- Prien am Chiemsee, Germany, where Saint Catherine is the patron-saint of the Town.

- Niedererbach, Germany

- Kremnica, Slovakia

- Katherine Swynford, England

- Kuldīga, Latvia

- Thomas de Brantingham

See also

- Fustuarium

- The Catherine wheel firework named after it

- Catherine wheel (disambiguation)

References

- ^ Abbott, Geoffrey (2007). What A Way To Go. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 36. ISBN 978-0312366568.

- ^ Kerrigan, Michael (2001/2007). The Instruments of Torture. Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-1599211275.

- ^ Abbott ibid.. pp. 40–41, 47.

- ^ Depicted in the contemporary woodcut An Aggravated Death Sentence, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

- ^ Evans, Richard J. (9 May 1996). Rituals of Retribution: Capital Punishment in Germany 1600-1987. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0198219682.

- ^ Chambers, Robert (1885). Domestic Annals of Scotland. Edinburgh: W & R Chambers.

- ^ Buchan, Peter (1828). Ancient Ballads and Songs of the North of Scotland. 1. Edinburgh, Scotland. p. 296. http://books.google.com/books?id=1h_gAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA296&dq=John+Kincaid+Warriston&cd=1#v=onepage&q=John%20Kincaid%20Warriston&f=false. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

- ^ "Executions in the U.S. 1608-2002: The Espy File" (PDF). Death Penalty Information Center. http://www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/documents/ESPYstate.pdf. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ^ Burrill, Alexander (1870). A Law Dictionary and Glossary. 2 (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Baker Voorheis and Co.. p. 620. http://books.google.com/books?id=ztgUAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA620&lpg=PA620&dq=prussia+1841+breaking+wheel#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 21 March 2010.

External links

- Probertenencyclopaedia - illustrated

- Greenblatt, Miriam Rulers and Their Times: Peter the Great and Tsarist Russia, Benchmark Books, ISBN 0-7614-0914-9

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "St. Catherine of Alexandria". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.Categories:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "St. Catherine of Alexandria". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.Categories:- Medieval instruments of torture

- Modern instruments of torture

- European instruments of torture

- Capital punishment

- Execution methods

- Execution equipment

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.