- Democratic deficit in the European Union

-

European Union

This article is part of the series:

Politics and government of

the European UnionPolicies and issuesDemocratic deficit in the European Union is a term used to refer to the view that the EU lacks democracy, arguably due to a lack of legitimacy in its institutions and/or lack of influence on the part of its citizens.[1] Opinions differ on how to remedy this, and it is also argued that the deficit is structural, i.e. cannot be resolved without changing the nature of the Union.[2][3]

Contents

Use and meaning of the term

The phrase democratic deficit is cited as first being used by David Marquand in 1979, referring to the then European Economic Community, the forerunner of the European Union.[4] 'Democratic deficit' in relation to the European Union, refers to a perceived lack of accessibility to the ordinary citizen, or lack of representation of the ordinary citizen, and lack of accountability of European Union institutions.[1][5]

The democratic deficit has been called a 'structural democratic deficit', in that it is inherent in the construction of the European Union as a supranational union that is neither a pure intergovernmental organization, nor a true federal state. The German Constitutional Court, for instance, argues that decision-making processes in the EU remain largely those of an international organization, which would ordinarily be based on the principle of the equality of states. The principle of equality of states and the principle of equality of citizens cannot be reconciled in a Staatenverbund.[2] In other words, in a supranational union or confederation (which is not a federal state) there is a problem of how to reconcile the principle of equality among nation states, which applies to international (intergovernmental) organizations, and the principle of equality among citizens, which applies within nation states.[3]

European executives

A notable response to the criticism that European integration has raised the powers of Executives in comparison to Parliaments has come from Andrew Moravcsik, who claims that the European Union has made Executives more accountable to their citizens. He notes that the actions of government ministers are no longer scrutinised simply at home, but in a wider European context and that ministers at home are no longer held to account solely for their domestic record, but also for their actions in Brussels- as for instance is demonstrated by some of the criticism Tony Blair received after concessions made over the UK rebate in 2005.

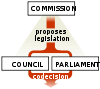

A more general point not related to Moravcsik's argument is that already mentioned, namely that the European Parliament has received a notable increase in powers since the Maastricht Treaty, with mechanisms such as co-decision procedures (between the Council of Ministers and European Parliament) being introduced and adopted in many policy areas. The European Parliament has also acquired something of a de facto scrutinising role where the conduct of Commissioners is concerned as evidenced by the resignation of the Santer Commission in 1999 under EP pressure in addition to explicit powers to veto Commission lineups - a power used in 2004 against the Barroso Commission. Nevertheless the debate over whether the European Union has increased the power of executives vis a vis parliaments remains highly contentious and should be considered in the context of increasing globalisation and security fears following 11 September.

The claim of executive dominance at European level is exaggerated, since this merely reproduces the informal situation at national level. There is a local form of executive dominance, as on average less than 15% of legislative initiatives from MPs become law when they don't have the backing of the executive, further more proposal from the executives become law, usually unamended.[6]

According to R. Daniel Kelemen, EU laws are more detailed than those of member states; in a similar way to federal states, the legal system is used to achieve political compliance by the member states, because of the decentralized nature of the political system. Decisions are taken at the EU level, but are overwhelmingly implemented by member states. In contrast, within member states, the same agents are usually responsible for both decision making and implementation. Thus EU law encroaches on the executive powers of national governments.[7][Need quotation to verify]

Voting in the council is usually done by qualified majority voting, and sometimes unanimity is required. This means that for the vast majority of EU legislation the corresponding national government has usually voted in favor in the Council. To give an example, up to September 2006, out of the 86 pieces of legislation adopted in that year the government of the United Kingdom had voted in favor of the legislation 84 times, abstained from voting twice and never voted against. [8]

European parliament

The supposition that the European Parliament is powerless is claimed to be due to its recent past as a consultative assembly and the implicit comparison with national parliaments, but this comparison arguably leads to false conclusions. Important differences from national parliaments are the role of committees, bipartisan voting, decentralized political parties, executive-legislative divide and absence of Government-opposition divide. All these traits are considered as signs of weakness or unaccountability, but these very same traits are found in the US House of Representatives to a lesser or greater degree, the European parliament is more appropriately compared with the US House of Representatives.[6]

Legislative initiative in the EU rests solely with the commission, while in member states it is shared between parliament and executive; however less than 15% of legislative initiatives from MPs become law when they do not have the backing of the executive. The European Parliament can only propose amendments, but unlike in national parliaments, the executive has no guaranteed majority to secure the passage of its legislation. In national parliaments, amendments are usually proposed by the opposition, who lack a majority for their approval and usually fail. But given the European Parliament's independence, and the need to obtain majority approval from it, proposals made by its many parties (none of which hold a majority alone) have an unusually high 80% success rate in the adoption of its amendments. Even in controversial proposals, its success rate is 30%, something not mirrored by national legislatures.[6]

Liberal Democrat (ELDR) MEP Chris Davies, says he has far more influence as a member of the European Parliament than he did as an opposition MP in the House of Commons. "Here I started to have an impact on day one", "And there has not been a month since when words I tabled did not end up in legislation."[9]

European elections

“ Turnout across Europe (1999) was higher than in the last US presidential election, and I don't hear people questioning the legitimacy of the presidency of the United States--Pat Cox[9] ” According to some observers,[10] the EU does not have a formal democratic deficit, but an informal one due to a social deficit. People believe that there is a democratic deficit so they do not go to vote, and thus create the democratic deficit by thinking there is one, a self generating situation, for which formal reform can do little to help.[10]

Transparency and judicial review

Scholars such as Andrew Moravcsik have argued that the decision making process in the EU is actually more transparent than the corresponding processes in member states. Notable reforms (partly motivated by a desire to respond to the initial criticisms) have made it comparatively easy for interest groups and citizens to access EU documents concerned with policy making including memos from debates in the Council of Ministers. Furthermore the actions of European actors come under scrutiny from not only the European Court of Justice (ECJ) but also from national courts and this extensive judicial review, it has been argued, is sufficient so as to ensure the accountability of policy makers in the EU.[citation needed]

Process promotes consensus

In response to arguments concerning policy bias some scholars[who?] have been keen to point out that the decision making process in the European Union relies heavily on consensus between agents. Qualified majority voting and unanimity are still used in Council votes and as such it has been argued that policies will inevitably reflect very centrist positions because any policy which leans too far to one side of the political spectrum will only require a small minority to oppose it for it to be rejected. Empirical evidence for either side of this debate has perhaps unsurprisingly been hard to come by due to the subjective nature of 'policy bias' arguments.

Reform under the Lisbon Treaty

The Treaty of Lisbon, which completed the process of ratification and came into force on December 1st 2009, modified the following elements which have been mentioned in relation to the alleged democratic deficit:

- The codecision is established as the standard legislative procedure, hence increasing the Parliament's ability to shape and propose legislation.

- It requires the Council (meetings between national governments) to meet in public at all legislative meetings.

- It ensures that national parliaments receive draft legislation earlier from the Commission.

- It gives national parliaments a new power to send any proposal back to the Commission for reconsideration.

- It confirms the principle of subsidiarity as fundamental to the Union.

- It creates a new citizens' right of initiative, obliging the Commission to consider any proposal for legislation that has the support of 1 million EU citizens.

References

- ^ a b "Glossary: Democratic deficit". European Commission. http://europa.eu/scadplus/glossary/democratic_deficit_en.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-06. "The democratic deficit is a concept invoked principally in the argument that the European Union and its various bodies suffer from a lack of democracy and seem inaccessible to the ordinary citizen because their method of operating is so complex. The view is that the Community institutional set-up is dominated by an institution combining legislative and government powers (the Council of the European Union) and an institution that lacks democratic legitimacy (the European Commission)."

- ^ a b "Press release no. 72/2009. Judgment of 30 June 2009" (Press release). German Federal Constitutional Court - Press office. 2009-06-30. http://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/en/press/bvg09-072en.html. Retrieved 2009-08-06. "The extent of the Union’s freedom of action has steadily and considerably increased, not least by the Treaty of Lisbon, so that meanwhile in some fields of policy, the European Union has a shape that corresponds to that of a federal state, i.e. is analogous to that of a state. In contrast, the internal decision-making and appointment procedures remain predominantly committed to the pattern of an international organisation, i.e. are analogous to international law; as before, the structure of the European Union essentially follows the principle of the equality of states. [. . .] Due to this structural democratic deficit, which cannot be resolved in a Staatenverbund, further steps of integration that go beyond the status quo may undermine neither the States’ political power of action nor the principle of conferral. The peoples of the Member States are the holders of the constituent power. [. . .] The constitutional identity is an inalienable element of the democratic self-determination of a people."

- ^ a b Pernice, Ingolf; Katharina Pistor (2004). "Institutional settlements for an enlarged European Union". In George A. Bermann and Katharina Pistor. Law and governance in an enlarged European Union: essays in European law. Hart Publishing. pp. 3–38. ISBN 9781841134260. "Among the most difficult challenges has been reconciling the two faces of equality – equality of states versus equality of citizens. In an international organization [. . .] the principle of equality of states would ordinarily prevail. However, the Union is of a different nature, having developed into a fully fledged 'supranational Union', a polity sui generis. But to the extent that such a polity is based upon the will of, and is constituted by, its citizens, democratic principles require that all citizens have equal rights."

- ^ Marquand, David (1979). Parliament for Europe. Cape. p. 64. ISBN 9780224017169. "The resulting 'democratic deficit' would not be acceptable in a Community committed to democratic principles."

Chalmers, Damian; et al. (2006). European Union law: text and materials. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780521527415. "'Democratic deficit' is a term coined in 1979 by the British political scientist . . . David Marquand ."

Meny, Yves (2003). "De La Democratie En Europe: Old Concepts and New Challenges". Journal of Common Market Studies 41: 1–13. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.t01-1-00408. "Since David Marquand coined his famous phrase 'democratic deficit' to describe the functioning of the European Community, the debate has raged about the extent and content of this deficit." - ^ Chryssochoou, Dimitris N. (007). "Democracy and the European polity". In Michelle Cini. European Union politics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, 2007. p. 360. ISBN 9780199281954.

- ^ a b c Kreppel, Amie (2006). "Understanding the European Parliament from a Federalist Perspective: The Legislatures of the USA and EU Compared". Center for European Studies, University of Florida. http://web.clas.ufl.edu/users/kreppel/COMFEDFINAL.pdf. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ^ The Rules of Federalism: Institutions and Regulatory Politics in the EU and Beyond (Dr. R. Daniel Kelemen)

- ^ http://www.consilium.europa.eu/cms3_fo/showPage.asp?id=1279&lang=EN

- ^ a b "The EU's democratic challenge". BBC News. 2003-11-21. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/3224666.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ a b http://www.eumap.org/journal/features/2005/demodef/avbelj

Further reading

- Follesdal, A and Hix, S. (2005) ‘Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU‘ European Governance Papers (EUROGOV) No. C-05-02

- Kelemen, Dr. R. Daniel; (2004) ‘The Rules of Federalism: Institutions and Regulatory Politics in the EU and Beyond‘ Harvard University Press

- Majone, G. (2005) 'Dilemmas of European Integration'.

- Marsh, M. (1998) ‘Testing the second-order election model after four European elections’ British Journal of Political Science Research. Vol 32.

- Moravcsik, A. (2002) ‘In defence of the democratic deficit: reassessing legitimacy in the European Union’ Journal of Common Market Studies. Vol 40, Issue 4.

- Reif, K and Schmitt, S. (1980) ‘Nine second-order national elections: a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results’ European Journal of Political Research. Vol 8, Issue 1.

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.