- Second Happy Time

-

America – Caribbean – Gibraltar – River Plate – Altmark – Texel – SC 7 – HX 84 – HX 106 – Berlin – Action of 4 April 1941 – Action of 9 May 1941 – Denmark Strait – Bismarck – Second Happy Time – Torpedo Alley – Action of 27 March 1942 – St. Lawrence – Action of 6 June 1942 – Laconia – PQ 17 – Casablanca – Barents Sea – Black May – North Cape – Operation Stonewall – Operation Teardrop – Action of 13 May 1944 – Ushant – Pierres Noires – Action of 9 February 1945 – Point Judith

TimelineThe Second Happy Time (codenamed Operation Paukenschlag or Operation Drumbeat), also known among German submarine commanders as the "American shooting season"[1] was the informal name for a phase in the Second Battle of the Atlantic during which Axis submarines attacked merchant shipping along the east coast of North America. The first "Happy time" was in 1940/41.

It lasted from January 1942 to about August of that year. German submariners named it the happy time or the golden time as defence measures were weak and disorganised,[2] and the U-boats were able to inflict massive damage with little risk. During the second happy time, Axis submarines sank 609 ships totaling 3.1 million tons for the loss of only 22 U-boats. This was roughly one quarter of all shipping sunk by U-boats during the entire Second World War.

Contents

Background

When war broke out between Germany and the United States on December 11, 1941, the U.S. was in a fortunate position. Where the other combatants had already lost thousands of trained sailors and airmen, and were experiencing shortages of ships and aircraft, the U.S. was at full strength. The U.S. had the opportunity to learn about modern naval warfare by observing the conflicts in the North Sea and the Mediterranean, and through a close relationship with the United Kingdom. The U.S. Navy had already gained significant experience countering U-boats in the Atlantic, particularly from April 1941 when President Roosevelt extended the "Pan-American Security Zone" east almost as far as Iceland. The United States had massive manufacturing capacity, including certainly the largest and possibly the most advanced electrical engineering in the world. Finally, the U.S. had a favourable geographical position from a defensive point of view: the port of New York, for example, was 3,000 miles to the west of the U-boat bases in Brittany.

U-boat commander Dönitz, however, saw the entry of the U.S. into the war as a golden opportunity to strike heavy blows in the tonnage war. The German Navy no longer had its surface tankers in the North Atlantic to refuel submarines (these had been sunk by Allied forces after Ultra intelligence revealed their locations)[citation needed] and the standard Type VII U-boat had insufficient range to patrol off the coast of North America, so the only weapons Dönitz had on hand were the larger Type IX boats. These, however, were less maneuverable and slower to submerge, making them much more vulnerable than the Type VIIs, and few in number.

Opening moves

Immediately after war was declared with the United States, Dönitz began to implement Operation Paukenschlag (often translated as "drumbeat", but literally it means "timpani beat"), requesting that 12 Type IX U-boats be made available for it. The Naval Staff in Berlin, however, insisted on retaining six of the precious Type IX boats for the Mediterranean theatre[citation needed] (where they could achieve little) and one of the remaining six encountered mechanical troubles. This left just five long-range submarines for the opening moves of the campaign.

Loaded with the maximum possible amounts of fuel, food and ammunition, the first of the five Type IXs left Lorient on 18 December 1941, the others following over the next few days. Each carried sealed orders to be opened after passing 20°W, and directing them to different parts of the North American coast. No charts or sailing directions were available: Kapitanleutnant Reinhard Hardegen of U-123, for example, was provided with two tourist guides to New York, one of which contained a fold-out map of the harbour.

Each U-boat made routine signals on exiting the Bay of Biscay, which were picked up by the British Y service and plotted in Rodger Winn's London Submarine Tracking Room, which was then able to follow the progress of the Type IXs across the Atlantic, and cable an early warning to the Royal Canadian Navy. Working on the slimmest of evidence, Winn correctly deduced the target area and passed a detailed warning to Admiral Ernest King in the United States of a "heavy concentration of U-boats off the North American seaboard", including the five boats already on station and further groups already in transit, 21 U-boats in all. Rear-Admiral Frank Leighton of the U.S. Combined Operations and Intelligence Center then informed the responsible area commanders, but little or nothing was done.

The primary target area was the "North Atlantic Coastal Frontier", commanded by Rear-Admiral Adolphus Andrews and covering the area from Maine to North Carolina. Andrews had practically no modern forces to work with: on the water he commanded seven Coast Guard cutters, four converted yachts, three 1919-vintage patrol boats, two gunboats dating to 1905, and four wooden submarine chasers. About 100 aircraft were available, but these were short-range models only suitable for training. As a consequence of the traditionally antagonistic relationship between the U.S. Navy and the Army Air Forces, all larger aircraft remained under USAAF control, and in any case the USAAF was neither trained nor equipped for anti-submarine work.

American response

British experience in the first two years of World War II, which included the massive losses incurred to British shipping during the "First Happy Time" confirmed that ships sailing in convoy — with or without escort — were far safer than ships sailing alone. British recommendations were that merchant ships should avoid obvious standard routings wherever possible; navigational markers, lighthouses, and other aids to the enemy should be removed, and a strict coastal blackout enforced. In addition, any available air and sea forces should perform daylight patrols to restrict the U-boats' flexibility.

None of this was attempted. Coastal shipping continued to sail along marked routes and burn normal steaming lights. On 12 January 1942 Admiral Andrews was warned that three or four U-boats were about to commence operations against coastal shipping, but he refused to institute a convoy system on the grounds that this would only provide the U-boats with more targets.

Despite the urgent need for action, little was done to try to combat the U-boats. The USN was desperately short of specialised anti-submarine vessels. President Roosevelt's 1941 decision to "loan" fifty obsolete World War I-era destroyers to Britain in exchange for foreign bases, was largely irrelevant. These destroyers had a large turning circle that made them ineffective for anti-submarine work, however their firepower would have been a significant defence against surface attack, which was the major threat in the early part of World War II. The massive new naval construction programme had prioritised other types of ships. While freighters and tankers were being sunk in coastal waters the destroyers that were available remained inactive in port. At least 25 Atlantic Convoy Escort Command Destroyers had been recalled to the U.S. East Coast at the time of the first attacks, including seven at anchor in New York Harbor.

When U-123 sank the 9,500 ton Norwegian tanker Norness within sight of Long Island in the early hours of 14 January, no warships were dispatched to investigate, allowing the U-123 to sink the 6,700 ton British tanker Coimbra off Sandy Hook on the following night before proceeding south towards New Jersey. By this time there were 13 destroyers idle in New York Harbor, yet still none were employed to deal with the immediate threat, and over the following nights U-123 was presented with a succession of easy targets, most of them burning navigation lamps. At times, U-123 was operating in shallow coastal waters that barely allowed it to conceal itself, let alone evade a depth charge attack.

For the five Type IX boats in the first wave of Operation Drumbeat, it was a bonanza. They cruised along the coast, safely submerged through the days, and surfacing at night to pick off merchant vessels outlined against the lights of the cities.

- Reinhard Hardegen in U-123 sank seven ships totalling 46,744 tons before he ran out of torpedoes and returned to base;

- Ernst Kals in Robert-Richard Zapp in U-66 sank five ships of 33,456 tons;

- Heinrich Bleichrodt in U-109 sank four ships of 27,651 tons; and

- Ulrich Folkers on his first patrol in U-125 sank only a single 6,666 ton vessel, for which he was criticised by Dönitz (though he would later win the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross.)

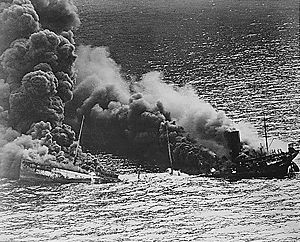

The tanker MS Pennsylvania Sun, torpedoed by U-571 on 15 July 1942

The tanker MS Pennsylvania Sun, torpedoed by U-571 on 15 July 1942

When the first wave of U-boats returned to port in early February, Dönitz wrote that each commander "had such an abundance of opportunities for attack that he could not by any means utilise them all: there were times when there were up to ten ships in sight, sailing with all lights burning on peacetime courses."

A significant failure in U.S. pre-war planning was lack of any ships suitable for convoy escort work. Escort vessels travel at relatively slow speeds, carry a large number of depth-charges, must be highly maneouvreable and must stay on station for long periods. Fleet destroyers are equipped for high speed and offensive action and not the ideal design for this type of work. There was no equivalent of the British Black Swan class sloops or the River-class frigate in the U.S. inventory when the war started. This blunder, highly surprising given that the USN had been involved in anti-submarine work in the Atlantic (see USS Reuben James) was further aggravated by the loss of the obsolete destroyers "loaned" to Britain through Lend-Lease, although these were barely suitable and vulnerable to counter-attack. There was also a lack of aircraft suitable for anti-submarine patrol and aircrew trained to use them.

Offers of civilian ships and aircraft to act as the Navy's "eyes" were repeatedly turned down, only to be accepted later when the situation was clearly critical and the admiral's claims to the contrary had become discredited.

By this time, the second wave of Type IX U-boats had arrived in American waters, and the third wave had reached its patrol area off the oil ports of the Caribbean. With such easy pickings available and all Type IX U-boats already committed, Dönitz began sending shorter-range Type VII U-boats to the U.S. East Coast as well. This required extraordinary measures: cramming every conceivable space with provisions, filling the fresh water tanks with diesel oil, and crossing the Atlantic at very low speed on a single engine to conserve fuel.

In the United States there was still no concerted response to the attacks. Overall responsibility rested with Admiral King, but King was preoccupied with the Japanese onslaught in the Pacific. Admiral Andrews' North Atlantic Coastal Frontier was expanded to take in South Carolina and renamed the Eastern Sea Frontier, but most of the ships and aircraft needed remained under the command of Admiral Royal E. Ingersoll, Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet, who was often at sea and unavailable to make decisions. Rodger Wynn's detailed weekly U-boat situation reports from the Submarine Tracking Room in London were available but ignored.

Popular alarm at the sinkings was dealt with by a combination of secrecy and misleading propaganda. The Navy confidently announced that many of the U-boats would "never enjoy the return portion of their voyage" but that, unfortunately, details of the sunken U-boats could not be made public lest the information aid the enemy. All citizens who had witnessed the sinking of a U-boat were asked to help keep the secrets safe.

The first sinking of a U-boat by a U.S. Navy ship off the coast of the U.S. did not occur until April 14, 1942, when the destroyer USS Roper sank the U-85. It has come to light in recent years that the famous "Loose Lips Sink Ships" propaganda campaign in the U.S. that started in 1942 was not so much designed to deny German agents knowledge of vessels' sailing times, but rather to keep American civilian morale high by reducing communication about how much shipping was being sunk during Operation Drumbeat.[citation needed]

Chronology of attacks off the U.S. East Coast

Chronology of attacks off the U.S. East Coast- 14 January - Panamanian tanker Norness sunk by U-123 at 40°26′24″N 70°54′29″W / 40.44°N 70.908°W[3]

- 18 January - United States tanker Allan Jackson sunk by U-66 at 35°57′N 74°20′W / 35.95°N 74.33°W (23 of 35 crewmen perish)[4]

- 18 January - United States tanker Malay damaged by U-123 at 35°25′N 75°23′W / 35.42°N 75.38°W (5 crewmen perish)[4]

- 19 January - United States steamship City of Atlanta sunk by U-123 at 35°42′N 75°21′W / 35.7°N 75.35°W (43 of 46 crewmen perish)[4]

- 19 January - Canadian steamship Lady Hawkins sunk by U-66 at 35°00′N 72°30′W / 35.0°N 72.5°W[4]

- 22 January - United States freighter Norvana sunk by U-123 south of Cape Hatteras (no survivors)[5]

- 23 January - United States collier Venore sunk by U-66 at 35°50′N 75°20′W / 35.83°N 75.33°W (17 of 41 crewmen perish)[5]

- 25 January - United States tanker Olney damaged by U-125 at 37°55′N 74°56′W / 37.92°N 74.93°W[5]

- 26 January - United States freighter West Ivis sunk by U-125 (all 45 crewmen perish)[5]

- 27 January - United States tanker Francis E. Powell sunk by U-130 at 37°45′N 74°53′W / 37.75°N 74.88°W (4 of 32 crewmen perish)[6]

- 27 January - United States tanker Halo damaged by U-130 at 35°33′N 75°20′W / 35.55°N 75.33°W[6]

- 30 January - United States tanker Rochester sunk by U-106 at 37°10′N 73°58′W / 37.17°N 73.97°W (3 of 32 crewmen perish)[6]

- 31 January - British tanker San Arcadio sunk by U-107 at 38°10′N 63°50′W / 38.17°N 63.83°W[6]

- 31 January - British tanker Tacoma Star sunk by U-109 at 37°33′N 69°21′W / 37.55°N 69.35°W[6]

- 2 February - United States tanker W.L.Steed sunk by U-103 at 38°25′N 72°43′W / 38.42°N 72.72°W (34 of 38 crewmen perish)[7]

- 3 February - Panamanian freighter San Gil sunk by U-103 at 38°05′N 74°40′W / 38.08°N 74.67°W (2 of 40 crewmen perish)[7]

- 4 February - United States tanker India Arrow sunk by U-103 at 38°48′N 73°40′W / 38.8°N 73.67°W (26 of 38 crewmen perish)[7]

- 5 February - United States tanker China Arrow sunk by U-103 at 38°44′N 73°18′W / 38.73°N 73.30°W[7]

- 6 February - United States freighter Major Wheeler sunk by U-107 (all 35 crewmen perish)[8]

- 8 February - British freighter Ocean Venture sunk by U-108 at 37°05′N 74°45′W / 37.08°N 74.75°W[8]

- 10 February - Canadian tanker Victolite sunk by U-564 at 36°12′N 67°14′W / 36.2°N 67.23°W[8]

- 15 February - Brazilian steamship Buarque sunk by U-432 at 36°35′N 75°20′W / 36.58°N 75.33°W[9]

- 18 February - Brazilian tanker Olinda sunk by U-432 at 37°30′N 75°00′W / 37.5°N 75.0°W[10]

- 19 February - United States tanker Pan Massachusetts sunk by U-128 at 28°27′N 80°08′W / 28.45°N 80.13°W (20 of 38 crewmen perish)[10]

- 20 February - United States freighter Azalea City sunk by U-432 at 38°00′N 73°00′W / 38.0°N 73.0°W (All of 38 crewmen perish)[11]

- 21 February - United States tanker Republic sunk by U-504 at 27°05′N 80°15′W / 27.08°N 80.25°W (5 of 29 crewmen perish)[11]

- 22 February - United States tanker Cities Service Empire sunk by U-128 at 28°00′N 80°16′W / 28.0°N 80.27°W (14 of 50 crewmen perish)[11]

- 22 February - United States tanker W.D.Anderson sunk by U-504 at 27°09′N 79°56′W / 27.15°N 79.93°W (35 of 36 crewmen perish)[11]

- 26 February - United States bulk carrier Marore sunk by U-432 at 35°33′N 74°58′W / 35.55°N 74.97°W[12]

- 26 February - United States tanker R.P.Resor sunk by U-578 at 39°47′N 73°26′W / 39.78°N 73.43°W (47 of 49 crewmen perish)[12]

- 28 February - United States destroyer Jacob Jones sunk by U-578 at 38°42′N 74°39′W / 38.70°N 74.65°W[12]

- 7 March - United States freighter Barbara sunk by U-126 at 20°00′N 73°56′W / 20.00°N 73.93°W[13]

- 7 March - United States freighter Cardonia sunk by U-126 at 19°53′N 73°27′W / 19.88°N 73.45°W[13]

- 7 March - Brazilian steamship Arbabutan sunk by U-155 at 35°15′N 73°55′W / 35.25°N 73.92°W[13]

- 9 March - Brazilian steamship Cayru sunk by U-94 at 39°10′N 72°02′W / 39.16°N 72.03°W[13]

- 10 March - United States tanker Gulftrade sunk by U-588 at 39°50′N 73°52′W / 39.84°N 73.87°W[14]

- 11 March - United States freighter Texan sunk by U-126 at 21°32′N 76°24′W / 21.53°N 76.4°W[14]

- 11 March - United States freighter Caribsea sunk by U-158 at 34°40′N 76°10′W / 34.67°N 76.16°W[14]

- 12 March - United States tanker John D. Gill sunk by U-158 at 35°55′N 77°39′W / 35.92°N 77.65°W (4 crewmen perish)[14]

- 12 March - United States freighter Olga sunk by U-126 at 23°39′N 77°00′W / 23.65°N 77.0°W[14]

- 12 March - United States freighter Colabee damaged by U-126 at 22°14′N 77°35′W / 22.23°N 77.58°W[14]

- 13 March - United States schooner Albert F. Paul sunk by U-332 at 26°00′N 72°00′W / 26.0°N 72.0°W (no survivors)[14]

- 13 March - Chilean freighter Tolten sunk by U-404 at 40°10′N 73°50′W / 40.16°N 73.84°W (15 of 16 crewmen perish)[14]

- 14 March - United States collier Lemuel Burrows sunk by U-404 at 39°12′N 74°16′W / 39.20°N 74.27°W[14]

- 15 March - United States tanker Ario sunk by U-158 at 34°20′N 76°39′W / 34.33°N 76.65°W (7 of 36 crewmen perish)[14]

- 15 March - United States tanker Olean sunk by U-158 at 34°24′N 76°29′W / 34.40°N 76.48°W[14]

- 16 March - United States tanker Australia sunk by U-332 at 35°07′N 75°22′W / 35.12°N 75.37°W[14]

- 16 March - British tanker San Demetrio sunk by U-404 at 37°03′N 73°50′W / 37.05°N 73.84°W[15]

- 17 March - United States tanker Acme damaged by U-124 at 35°06′N 76°40′W / 35.1°N 76.67°W[15]

- 17 March - Greek freighter Kassandra Louloudi sunk by U-124 four mile off Diamond Shoals gas buoy[15]

- 17 March - Honduran freighter Ceiba sunk by U-124 at 35°43′N 73°49′W / 35.72°N 73.82°W[15]

- 18 March - United States tanker E.M.Clark sunk by U-124 at 34°50′N 75°35′W / 34.84°N 75.58°W[15]

- 18 March - United States tanker Papoose sunk by U-124 at 34°17′N 76°39′W / 34.28°N 76.65°W[15]

- 18 March - United States tanker W.E.Hutton sunk by U-332 at 34°05′N 76°40′W / 34.08°N 76.67°W (13 of 36 crewmen perish)[15]

- 19 March - United States freighter Liberator sunk by U-332 at 35°05′N 75°30′W / 35.08°N 75.50°W (5 crewmen perish)[15]

- 20 March - United States tanker Oakmar sunk by U-71 at 36°21′N 68°50′W / 36.35°N 68.84°W (6 of 36 crewmen perish)[15]

- 21 March - United States tanker Esso Nashville sunk by U-124 at 33°35′N 77°22′W / 33.58°N 77.37°W[15]

- 21 March - United States tanker Atlantic Sun damaged by U-124[15]

- 22 March - United States tanker Naeco sunk by U-124 at 33°59′N 76°40′W / 33.98°N 76.67°W (24 of 39 crewmen perish)[15]

- 25 March - Dutch tanker Ocana sunk by U-552 at 42°36′N 64°25′W / 42.6°N 64.42°W[15]

- 26 March - United States Q-ship USS Atik sunk by U-123 at 36°00′N 70°00′W / 36.0°N 70.0°W (All of 139 crewmen perish)[16]

- 26 March - United States tanker Dixie Arrow sunk by U-71 at 34°59′N 75°33′W / 34.98°N 75.55°W (11 of 33 crewmen perish)[16]

- 26 March - Panamanian tanker Equipoise sunk by U-160 at 36°36′N 74°45′W / 36.6°N 74.75°W[16]

- 29 March - United States steamship City of New York sunk by U-160 at 35°16′N 74°25′W / 35.27°N 74.42°W (24 of 157 crewmen perish)[16]

- 31 March - United States tug Menominee and barges Allegheny and Barnegat sunk by U-754 at 37°34′N 75°25′W / 37.57°N 75.42°W[16]

- 31 March - United States tanker Tiger sunk by U-754 (1 of 43 crewmen perishes)[17]

- 3 April - United States freighter Otho sunk by U-754 at 36°25′N 71°57′W / 36.42°N 71.95°W (31 of 53 crewmen perish)[17]

- 4 April - United States tanker Byron D. Benson sunk by U-552 at 36°08′N 75°32′W / 36.13°N 75.53°W (9 of 37 crewmen perish)[17]

- 6 April - United States tanker Bidwell damaged by U-160 34°25′N 75°57′W / 34.42°N 75.95°W (1 of 33 crewmen perishes)[18]

- 7 April - Norwegian freighter Lancing sunk by U-552 off Cape Hatteras[18]

- 7 April - British tanker British Splendour sunk by U-552 off Cape Hatteras[18]

- 8 April - United States tanker Oklahoma damaged by U-123 at 31°18′N 80°59′W / 31.3°N 80.98°W (19 of 37 crewmen perish)[18]

- 8 April - United States tanker Esso Baton Rouge damaged by U-123 at 31°13′N 80°05′W / 31.22°N 80.08°W (3 of 39 crewmen perish)[18]

- 9 April - United States freighter Esparta sunk by U-123 30°46′N 81°11′W / 30.77°N 81.18°W (1 of 40 crewmen perishes)[19]

- 9 April - United States freighter Malchace sunk by U-160 at 34°28′N 75°56′W / 34.47°N 75.93°W (1 of 29 crewmen perishes)[19]

- 9 April - United States tanker Atlas sunk by U-552 at 34°27′N 76°16′W / 34.45°N 76.27°W (2 of 34 crewmen perish)[19]

- 9 April - tanker Tamaulipas sunk by U-552 at 34°25′N 76°00′W / 34.42°N 76.0°W (2 of 37 crewmen perish)[19]

- 10 April - United States tanker Gulfamerica sunk by U-123 at 30°14′N 81°18′W / 30.23°N 81.3°W (19 of 48 crewmen perish)[19]

- 11 April - United States tanker Harry F. Sinclair Jr. damaged by U-203 at 34°25′N 76°30′W / 34.42°N 76.5°W (10 of 36 crewmen perish)[19]

- 11 April - British steamship Ulysses sunk by U-160 at 34°23′N 75°35′W / 34.38°N 75.58°W[19]

- 12 April - Panamanian tanker Stanvac Melbourne sunk by U-203 at 33°53′N 77°29′W / 33.88°N 77.48°W[19]

- 12 April - United States freighter Leslie sunk by U-123 at 28°37′N 80°25′W / 28.62°N 80.42°W (3 of 32 crewmen perish)[19]

- 14 April - British freighter Empire Thrush sunk by U-203 at 35°12′N 75°14′W / 35.2°N 75.23°W[20]

- 14 April - United States freighter Margaret sunk by U-571 at 35°12′N 75°14′W / 35.2°N 75.23°W (All of 29 crewmen perish)[20]

- 15 April - United States freighter Robin Hood sunk by U-575 at 38°39′N 66°38′W / 38.65°N 66.63°W (14 of 38 crewmen perish)[20]

- 16 April - United States freighter Alcoa Guide sunk by U-123 at 35°34′N 70°08′W / 35.57°N 70.13°W (6 of 34 crewmen perish)[20]

- 17 April - Argentine tanker Victoria damaged by U-201 at 36°41′N 68°48′W / 36.68°N 68.8°W[20]

- 18 April - United States tanker Axtell J. Byles damaged by U-136 at 35°32′N 75°19′W / 35.53°N 75.32°W[21]

- 19 April - United States freighter Steel Maker sunk by U-136 at 33°05′N 70°36′W / 33.08°N 70.6°W (1 of 45 crewmen perishes)[21]

- 20 April - United States freighter West Imboden sunk by U-752 at 41°14′N 65°54′W / 41.23°N 65.9°W[21]

- 21 April - United States freighter Pipestone County sunk by U-576 at 37°35′N 66°20′W / 37.58°N 66.33°W[21]

- 21 April - United States freighter San Jacinto sunk by U-201 at 31°10′N 70°45′W / 31.16°N 70.75°W (14 of 183 crewmen perish)[21]

- 29 April - United States tanker Mobiloil sunk by U-108 at 26°10′N 66°15′W / 26.16°N 66.25°W[22]

- 29 April - United States tanker Federal sunk by U-507 at 21°13′N 76°05′W / 21.22°N 76.08°W (5 of 33 crewmen perish)[22]

- 2 May - United States armed yacht Cythera sunk by U-402 off North Carolina (66 of 68 crewmen perish)[21]

- 4 May - United States tanker Norlindo sunk by U-507 at 24°57′N 84°00′W / 24.95°N 84.0°W (5 of 28 crewmen perish)[23]

- 4 May - United States tanker edit] Counter measures get under way

The decision to implement convoys and blackout coastal towns to make ships more difficult to see came slowly. The situation began to change in April when Andrews implemented a limited convoy system in which ships traveled only during daylight hours. Full convoys were in operation by mid-May, resulting in an immediate reduction of Allied shipping losses off the East Coast as Dönitz withdrew the U-boats to seek easier pickings elsewhere. The convoy system was later extended to the Gulf of Mexico with similar dramatic effects, thus proving that Andrews' initial rejection of the convoy system was wrong.

In March, 24 Royal Navy anti-submarine trawlers and 10 corvettes were transferred from the UK for the defence of the U.S. East Coast. That same month the Royal Canadian Navy began escorting convoys between Boston and Halifax. The British also transferred 53 Squadron, RAF Coastal Command to Quonset Point, Rhode Island to protect New York Harbor during July 1942. This squadron moved to Trinidad in August, with a U.S. squadron, to protect the critical sea lanes from the Venezuelan oil fields and then back to Norfolk, Virginia until the end of 1942. Royal Navy and Royal Canadian Navy ships took over escort duties in the Caribbean and on the Aruba–New York tanker run. Fast CU convoys were organized to maintain petroleum fuel stockpiles on the British Isles.[34]

The Kriegsmarine, while enormously effective during this period, did not go without losses. Sinkings of German U-boats at the hands of United States forces during this time included:

- U-85: sunk 14 April by destroyer USS Roper in position 35°55′01″N 75°13′01″W / 35.917°N 75.217°W off Cape Hatteras,[20] first sinking in U.S. waters

- U-352: sunk 9 May by cutter Icarus in position 34°12′00″N 76°34′59″W / 34.2°N 76.583°W off Cape Hatteras[26]

- U-157: sunk 13 June by cutter Havana, Cuba[33]

- U-158: sunk 30 June by Mariner aircraft (USN VP-74) in position 32°49′59″N 67°28′01″W / 32.833°N 67.467°W west of Bermuda[35]

- U-215: sunk 3 July by Armed ASW Trawler HMS Le Tiger in position 41°29′N 66°23′W / 41.48°N 66.38°W by depth charges

- U-701: sunk 7 July by Lockheed Hudson aircraft in position 34°49′59″N 74°55′01″W / 34.833°N 74.917°W off Cape Hatteras[36]

- Colón, Panama[37]

- Kingfisher aircraft and ramming by the U.S. motor vessel Unicoi in position 34°51′00″N 75°22′01″W / 34.85°N 75.367°W off Cape Hatteras[38]

- U-166: sunk 30 July by US Navy patrol craft, PC 566, in position 28°31′01″N 90°45′00″W / 28.517°N 90.75°W in the Gulf of Mexico,[39] the only U-boat sunk in the Gulf of Mexico during World War II

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ Miller, Nathan: War at Sea: A Naval History of World War II. Oxford University Press, 1997, p. 295. ISBN 0195110382

- ^ Gannon, Michael (1991). Operation Drumbeat. New York: Harper Collins. pp. 296. ISBN 0-06-092088-2.

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.69

- ^ a b c d Cressman (2000) p.70

- ^ a b c d Cressman (2000) p.71

- ^ a b c d e Cressman (2000) p.72

- ^ a b c d Cressman (2000) p.73

- ^ a b c Cressman (2000) p.74

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.75

- ^ a b Cressman (2000) p.76

- ^ a b c d Cressman (2000) p.77

- ^ a b c Cressman (2000) p.79

- ^ a b c d Cressman (2000) p.81

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cressman (2000) p.82

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cressman (2000) p.83

- ^ a b c d e Cressman (2000) p.84

- ^ a b c Cressman (2000) p.85

- ^ a b c d e Cressman (2000) p.86

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Cressman (2000) p.87

- ^ a b c d e f Cressman (2000) p.88

- ^ a b c d e f Cressman (2000) p.89

- ^ a b Cressman (2000) p.90

- ^ a b c d e f Cressman (2000) p.91

- ^ a b Cressman (2000) p.92

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.93

- ^ a b c d e f Cressman (2000) p.94

- ^ a b c d Cressman (2000) p.95

- ^ a b c d Cressman (2000) p.96

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.97

- ^ a b Cressman (2000) p.98

- ^ a b Cressman (2000) p.99

- ^ a b Cressman (2000) p.100

- ^ a b c Cressman (2000) p.103

- ^ http://www.iwm.org.uk/upload/package/8/atlantic/can3942.htm

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.106

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.108

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.109

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.110

- ^ Cressman (2000) p.112

- Bibliography

- Baurer, E. The History of the Second World War.

- Behrens, C. B. A. Merchant Shipping and the Demands of War. London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1955.

- Cressman, Robert J. (2000). The Official Chronology of the U.S. Navy in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-149-1.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. A History of U.S. Naval Operations in World War II Vol. I: The Battle of the Atlantic, September 1939–May 1943. Boston: Little, Brown, 1947.

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War Vol. IV: The Grand Alliance. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1950.

- Ellis, John. The World War II Databook: The Essential Facts and Figures for All the Combatants. London: Aurum Press, 1993. ISBN 1854102540.

- Gannon, Michael. Operation Drumbeat: The Dramatic True Story of Germany's First U-Boat Attacks Along the American Coast in World War II. New York: Harper & Row, 1990. ISBN 0060161558.

- Roskill, Stephen Wentworth. The War at Sea, 1939–1945 Volume II The Period of Balance. London: H.M. Stationery Office, 1956.

- U-Boat War. BFS Video, May 2001. ISBN 6304876904. A three part documentary.

External links

Categories:- World War II Battle of the Atlantic

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

Look at other dictionaries:

time — time1 [ taım ] noun *** ▸ 1 quantity clock measures ▸ 2 period ▸ 3 occasion/moment ▸ 4 time available/needed ▸ 5 how fast music is played ▸ + PHRASES 1. ) uncount the quantity that you measure using a clock: Time seemed to pass more quickly than… … Usage of the words and phrases in modern English

time — I UK [taɪm] / US noun Word forms time : singular time plural times *** Metaphor: Time is like money or like something that you buy and use. I ve spent a lot of time on this project. ♦ We are running out of time. ♦ You have used up all the time… … English dictionary

time — time1 W1S1 [taım] n ▬▬▬▬▬▬▬ 1¦(minutes/hours etc)¦ 2¦(on a clock)¦ 3¦(occasion)¦ 4¦(point when something happens)¦ 5¦(period of time)¦ 6¦(available time)¦ 7 all the time 8 most of the time 9 half the time 10 at tim … Dictionary of contemporary English

Happy Days (play) — Happy Days is a play in two acts, written in English, by Samuel Beckett. He began the play on 8th October 1960 [Knowlson, J., Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett (London: Bloomsbury, 1996), p 475] and it was completed on 14th May 1961.… … Wikipedia

Happy Birthday to You — also known more simply as Happy Birthday , is a traditional song that is sung to celebrate the anniversary of a person s birth. According to the 1998 Guinness Book of World Records , Happy Birthday to You is the most well recognized song in the … Wikipedia

Happy Rockefeller — Margaretta Happy Rockefeller in 1973 Second Lady of the United States In office December 19, 1974 – January 20, 1977 … Wikipedia

Happy Christmas (Jessica Simpson album) — Happy Christmas Studio album by Jessica Simpson Released November 22 … Wikipedia

Happy Corner — Happy Corner, also known as Aluba ( hitting the tree in Taiwan), or Pole racking in Great Britain, is a practice in which a person s groin is cornered rudely against a pole shaped solid object.cope and variationsIt is popular as a hazing ritual… … Wikipedia

Happy slapping — is a fad in which someone attacks an unsuspecting victim while an accomplice records the assault (commonly with a camera phone or a smartphone). Most happy slappers are teenagers or young adults. Several incidents have been extremely violent, and … Wikipedia

Happy Tree Friends — title card Genre Black comedy Splatter Format … Wikipedia