- Javanese language

-

Not to be confused with Japanese language.

Javanese ꦧꦱꦗꦮ (Basa Jawa) Spoken in Java (Indonesia)

Peninsular Malaysia

Suriname

New CaledoniaNative speakers 85 million (2000 census) Language family Austronesian- Malayo-Polynesian

- Nuclear MP

- Javanese

- Nuclear MP

Writing system Javanese alphabet (optional)

Pegon alphabet (religious use)

Latin (general)Language codes ISO 639-1 jv ISO 639-2 jav ISO 639-3 variously:

jav – Javanese

jvn – Caribbean Javanese

jas – New Caledonian Javanese

osi – Osing language

tes – Tenggerese

kaw – Old JavaneseThis page contains IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. Javanese language (Javanese: basa Jawa (ꦧꦱꦗꦮ), Indonesian: bahasa Jawa) is the language of the Javanese people from the central and eastern parts of the island of Java, in Indonesia. In addition, there are also some pockets of Javanese speakers in the northern coast of western Java. It is the native language of more than 75,500,000 people.

The Javanese language is part of the Austronesian family, and is therefore related to Indonesian and other Malay varieties. Most speakers of Javanese also speak Indonesian for official and commercial purposes and to communicate with non-Javanese Indonesians.

Outside Indonesia, there are some Javanese-speaking people in neighboring countries such as Malaysia and Singapore. In addition there are also people of Javanese descent in Suriname (the former Dutch Guiana until 1975), who speak a creole descendant of the language. The Javanese speakers in Malaysia are especially found in the states of Selangor and Johor. For distribution in other parts, as far as Suriname, see Demographic distribution of Javanese speakers below.

Introduction

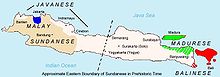

Javanese is a Nuclear Malayo-Polynesian language, but is otherwise not particularly close to other languages and is difficult to classify. It is however not too dissimilar from neighboring languages such as Malay, Sundanese, Madurese, and Balinese.

Javanese is spoken in Central and East Java, as well as on the north coast of West Java. In Madura, Bali, Lombok and the Sunda region of West Java, Javanese is also used as a literary language. It was the court language in Palembang, South Sumatra, until their palace was sacked by the Dutch in the late 18th century.

Javanese can be regarded as one of the classical languages of the world, with a vast literature spanning more than twelve centuries. Scholars divide the development of Javanese language in four different stages:

- Old Javanese, from the 9th century

- Middle Javanese, from the 13th century

- New Javanese, from the 16th century

- Modern Javanese, from the 20th century (this classification is not used universally)

Javanese is written with the Javanese script, Arabo-Javanese script, Arabic script (modified for Javanese) and Latin script.[1]

Although not currently an official language anywhere, Javanese is the Austronesian language with the largest number of native speakers. It is spoken or understood by approximately 80 million people. At least 45% of the total population of Indonesia are of Javanese descent or live in an area where Javanese is the dominant language. Five out of six Indonesian presidents since 1945 are of Javanese descent. It is therefore not surprising that Javanese has a deep impact on the development of Indonesian, the national language of Indonesia, which is a modern dialect of Malay.

There are three main dialects of Modern Javanese: Central Javanese, Eastern Javanese and Western Javanese. There is a dialect continuum from Banten in the extreme west of Java to Banyuwangi, in the foremost eastern corner of the island. All Javanese dialects are more or less mutually intelligible.

Phonology

The phonemes of Modern Standard Javanese.[2]

Vowels

Front Central Back i u e ə o a The vowels /i u e o/ are pronounced [ɪ ʊ ɛ ɔ] respectively in closed syllables.[2] In open syllables, /e o/ are also [ɛ ɔ] when the followinɡ vowel is /i u/ in an open syllable, or /ə/, or identical (/e...e/, /o...o/). The main characteristic of the standard dialect of Surakarta is that /a/ is pronounced [ɔ] in word-final open syllables, and in any open penultimate syllable before such an [ɔ].

Consonants

Labial Dental/

AlveolarRetroflex Palatal Velar Glottal Nasal m ɳ ɲ ŋ Plosive/Affricate p b̥ t d̥ ʈ ɖ̥ tʃ dʒ̊ k ɡ̊ ʔ Fricative ʂ h Approximant Central ɽ j w Lateral ɭ The Javanese voiced phonemes are not in fact voiced but voiceless, with breathy voice on the following vowel.[2] In The sounds of the world's languages, the distinction of phonation in the plosives is described as one of stiff voice versus slack voice.[3]

A Javanese syllable can be of the following type:[clarification needed] CSVC. C=consonant, S= sonorant (/j/, /r/, /l/, /w/ or any nasal consonant) and V=vowel. In Modern Javanese, a bi-syllabic root is of the following type: nCsvVnCsvVC. As in other Austronesian languages, native Javanese roots consist of two syllables; words consisting of more than three syllables are broken up into groups of bi-syllabic words for pronunciation.

Javanese, together with Madurese, are the only languages of Western Indonesia to possess a distinction between retroflex and dental phonemes.[2] (Madurese also possesses aspirated phonemes including at least one aspirated retroflex phoneme.) These letters are transcribed as "th" and "dh" in the modern Roman script, but previously by the use of a dot: "ṭ" and "ḍ". Some scholars[who?] assume this might be an influence of the Sanskrit, but others[who?] believe this could be an independent development within the Austronesian super family. Incidentally, a sibilant before a retroflex stop in Sanskrit loanwords is pronounced as a retroflex sibilant whereas in modern Indian languages it is pronounced as a palatal sibilant. Though Acehnese and Balinese also possess a retroflex voiceless stop, this is merely an allophone of /t/.

Morphology

Javanese, like other Austronesian languages, is an agglutinative language, where base words are modified through extensive use of affixes.

Syntax

Modern Javanese usually employs SVO word order. However, Old Javanese particularly had VSO or sometimes VOS word orders. Even in Modern Javanese archaic sentences using VSO structure can still be made.

Examples:

- Modern Javanese: "Dhèwèké (S) teka (V) ing (pp.) keraton (O)".

- Old Javanese: "Teka (V) ta (part.) sira (S) ri (pp.) -ng (def. art.) kadhatwan (O)".[4]

Both sentences mean: "He (S) comes (V) in (pp.) the (def. art.) palace (O)". In the Old Javanese sentence, the verb is placed at the beginning and is separated by the particle ta from the rest of the sentence. In Modern Javanese the definite article is lost in prepositions (it is expressed in another way).

Verbs are not inflected for person or number. Tense is not indicated either, but is expressed by auxiliary words such as "yesterday", "already", etc. There is also a complex system of verb affixes to express the different status of the subject and object.

However, in general the structure of Javanese sentences both Old and Modern can be described using the so-called topic–comment model without having to refer to classical grammatical or syntactical categories such as the aforementioned subject, object, predicate, etc. The topic is the head of the sentence; the comment is the modifier. So our Javanese above-mentioned sentence could then be described as follows: Dhèwèké = topic; teka = comment; ing keraton = setting.

Vocabulary

Javanese has a rich vocabulary, with many foreign loan words as well as the native Austronesian base. Sanskrit has had a deep and lasting impact on the vocabulary of the Javanese language. The "Old Javanese–English Dictionary", written by professor P.J. Zoetmulder in 1982, contains approximately 25,500 entries, over 12,600 of which are borrowings from Sanskrit.[5] Clearly this large number is not an indication of usage, but it is an indication that the Ancient Javanese knew and employed these Sanskrit words in their literary works. In any given Old Javanese literary work, approximately 25% of the vocabulary is derived from Sanskrit. In addition, many Javanese personal names have clearly recognisable Sanskrit roots.

Many Sanskrit words are still in current usage. Modern Javanese speakers refer to much of the Old Javanese and Sanskrit words as kawi words, which may be roughly translated as "literary". However the so-called kawi words also contain some Arabic words. Furthermore there has been significant word borrowing from Arabic, Dutch and Malay as well, but none as extensively as from Sanskrit.

There are far fewer Arabic loanwords in Javanese than in Malay. These Arabic loanwords are usually concerned with Islamic religion, but some words have entered the basic vocabulary, such as pikir ("to think", from the Arabic fikr), badan ("body"), mripat ("eye", thought to be derived from the Arabic ma'rifah, meaning "knowledge" or "vision"). However, these Arabic words typically have native Austronesian and/or Sanskrit equivalents. In the cases mentioned, pikir = galih, idhĕp (Austronesian), manah, cipta, or cita (Sanskrit), badan = awak (Austronesian), slira, sarira, or angga (Sanskrit), and mripat = mata (Austronesian), soca, or netra (Sanskrit).

Dutch loanwords usually have the same form and meaning as in Indonesian, but there are a few exceptions. Consider this table:

Javanese Indonesian Dutch English pit sepeda fiets bicycle pit montor sepeda motor motorfiets motorcycle sepur kereta api spoor, i.e. (rail)track train The latter is interesting, as the word sepur also exists in Indonesian. The Indonesian word has preserved the literal Dutch meaning of "railway tracks", while the Javanese word follows Dutch figurative use, where "spoor" (lit. "rail") is used as metonymy for "trein" (lit. "train"). (Compare the corresponding metonymic use in English: "to travel by rail" may be used for "to travel by train".)

Malay was the lingua franca of the Indonesian archipelago before the proclamation of Indonesian independence in 1945, and Indonesian, which was based on Malay, is now the official national language of Indonesia. As a consequence, there has been an influx of Malay and Indonesian vocabulary into Javanese recently. Many of these words are concerned with bureaucracy or politics.

Politeness

A Javanese noble lady (left) when addressing her servant, would use different set of vocabulary from what her servant would use in return. (Studio portrait of painter Raden Saleh's wife and a servant, colonial Batavia. 1860–1872.)

A Javanese noble lady (left) when addressing her servant, would use different set of vocabulary from what her servant would use in return. (Studio portrait of painter Raden Saleh's wife and a servant, colonial Batavia. 1860–1872.)

Javanese speech varies depending on social context, yielding three distinct styles, or registers.[6] Each style employs its own vocabulary, grammatical rules and even prosody. This is not unique to Javanese; neighboring Austronesian languages as well as East Asian languages such as Korean and Japanese share similar constructions.

In Javanese these styles are called:

- Ngoko (or even spelled as Ngaka) is informal speech, used between friends and close relatives. It is also used by persons of higher status to persons of lower status, such as elders to younger people or bosses to subordinates.

- Madya is the intermediary form between ngoko and krama. An example of the context where one would use madya is an interaction between strangers on the street, where one wants to be neither too formal nor too informal. The term is from Sanskrit madya, "middle".[7]

- Krama is the polite and formal style. It is used between persons of the same status who do not wish to be informal. It is also the official style for public speeches, announcements, etc. It is also used by persons of lower status to persons of higher status, such as youngsters to elder people or subordinates to bosses. The term is from Sanskrit krama, "in order".[7]

In addition, there are also "meta-style" words – the honorifics and humilifics. When one talks about oneself, one has to be humble. But when one speaks of someone else with a higher status or to whom one wants to be respectful, honorific terms are used. Status is defined by age, social position and other factors. The humilific words are called krama andhap words while the honorific words are called krama inggil words. For example, children often use the ngoko style, but when talking to the parents they must use both krama inggil and krama andhap.

Below some examples are provided to explain these different styles.

- Ngoko: Aku arep mangan (I want to eat)

- Madya: Kula ajeng nedha.

- Krama:

- (Neutral) Kula badhé nedhi.

- (Humble) Dalem badhé nedhi.

The most polite word for "eat" is dhahar. But it is forbidden to use any most polite word for self expression, except when talking with lower status people, and in this case, ngoko style is used. The use of most polite words is only for speaking to other, especially upper status, people, as shown below:

- Mixed:

- (Honorific – Addressed to someone with a high(er) status.) Bapak kersa dhahar? (Do you want to eat? Literal meaning: Does father want to eat?)

- (reply towards persons with lower status, expressing self superiority) Iya, aku kersa dhahar. (Yes, I want to eat.)

- (reply towards persons with lower status, but without having the need to express one's superiority) Iya, aku arep mangan.

- (reply towards persons with the same status) Inggih, kula badhé nedha.

The use of these different styles is complicated and requires thorough knowledge of the Javanese culture. This is one element that makes it difficult for foreigners to learn Javanese. On the other hand, these different styles of speech are actually not mastered by the majority of Javanese. Most people only master the first style and a rudimentary form of the second style. People who can correctly use the different styles are held in high esteem.

Dialects of modern Javanese

There are three main groups of Javanese dialects based on the sub region where the speakers live. They are: Western Javanese, Central Javanese and Eastern Javanese. The differences between these dialectical groups are primarily pronunciation and, to a lesser extent, vocabulary. All Javanese dialects are more or less mutually intelligible.

The Central Javanese variant, based on the speech of Surakarta[8] (and also to a degree of Yogyakarta), is considered as the most "refined" Javanese dialect. Accordingly standard Javanese is based on this dialect. These two cities are the seats of the four Javanese principalities, heirs to the Mataram Sultanate, which once reigned over almost the whole of Java and beyond. Speakers spread from north to south of the Central Java province and utilize many dialects, such as Muria and Semarangan, as well as Surakarta and Yogyakarta. To a lesser extent, there are also dialects such as those used in Pekalongan or Dialek Pantura and Kebumen (a variation of Banyumasan). The variations of Javanese dialect in Central Java are said to be so plentiful that almost all administrative regions (kabupaten) have their own native slang that is only recognizable by people from that region, but those minor dialects are not distinctive to most Javanese speakers.

In addition to Central Java and Yogyakarta provinces, Central Javanese is also used in the western part of East Java province. For example, Javanese spoken in the Madiun region bears a strong influence of Surakarta Javanese (as well as Javanese spoken in Ponorogo, Pacitan, and Tulungagung), while Javanese spoken in Bojonegoro and Tuban is similar to that spoken in the Pati region (Muria dialect).

Western Javanese, spoken in the western part of the Central Java province and throughout the West Java province (particularly in the north coast region), contains dialects which are distinct for their Sundanese influences and which still maintain many archaic words. The dialects include North Banten, Banyumasan, Tegal, Jawa Serang, North coast, Indramayu (or Dermayon) and Cirebonan (or Basa Cerbon).

Eastern Javanese speakers range from the eastern banks of Brantas River in Kertosono, Nganjuk to Banyuwangi, comprising the majority of the East Java province, excluding Madura island. However, the dialect has been influenced by Madurese, and is sometimes referred to as Surabayan speech.

The most aberrant dialect is spoken in Balambangan (or Banyuwangi) in the eastern-most part of Java. It is generally known as Basa Osing. Osing is the word for negation and is a cognate of the Balinese tusing, Balinese being the neighboring language directly to the east. In the past this area of Java was in possession of Balinese kings and warlords.

In addition to these three main Javanese dialects, there is Surinamese Javanese. Surinamese Javanese is mainly based on the Central Javanese dialect, especially from the Kedu residency.

Phonetic Differences

Phoneme /i/ at closed ultima is pronounced as [ɪ] in Central Javanese (Surakarta – Yogyakarta dialect), as [i] in Western Javanese (Banyumasan dialect) or as [ɛ] in Eastern Javanese.

Phoneme /u/ at closed ultima is pronounced as [ʊ] in Central Javanese, as [u] in Western Javanese or as [ɔ] in Eastern Javanese.

Phoneme /a/ at closed ultima in Central Javanese is pronounced as [a] and at open ultima as [ɔ]. Meanwhile unregarding its position, it is pronounced as [a] in Western Javanese and as [ɔ] in Eastern Javanese.

Dialectal Phonetics Phoneme Orthography Central Javanese (standard) Western Javanese Eastern Javanese English /i/ getih [ɡətɪh] [ɡətih] [ɡətɛh] blood /u/ abuh [aβʊh] [aβuh] [aβɔh] swollen /a/ lenga [ləŋɔ] [ləŋaʔ] [ləŋɔ] oil /a/ kancamu [kancamu] [kancane kowɛʔ] [kɔncɔmu] your friend Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Javanese language is enriched by dialectal words. For example, to get the meaning of "you", Western Javanese speakers say rika /rikaʔ/, Eastern Javanese use kon /kɔn/ or koen/kɔən/, and Central Javanese speakers say kowé /kowe/. Another example is the expression of "how": the Tegal dialect of Western Javanese uses kepribèn /kəpriben/, the Banyumasan dialect of Western Javanese employs kepriwé /kəpriwe/ or kepriwèn /kəpriwen/, Eastern Javanese speakers say yok apa /jɔʔ ɔpɔ/ – originally means "like what" (Javanese: kaya apa) or kepiyé /kəpije/, and Central Javanese speakers say piye /pije/ or kepriyé /kəprije/.

History

Old Javanese

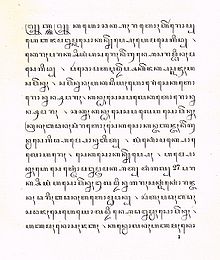

Main article: Old Javanese language Palm leaf manuscript of Kakawin Sutasoma, a 14th century Javanese poem.

Palm leaf manuscript of Kakawin Sutasoma, a 14th century Javanese poem.

While evidence of writing in Java dates to the Sanskrit "Tarumanegara inscription" of 450, the oldest example written entirely in Javanese, called the "Sukabumi inscription", is dated March 25, 804. This inscription, located in the district of Pare in the Kediri regency of East Java, is actually a copy of the original, dated some 120 years earlier; only this copy has been preserved. Its contents concern the construction of a dam for an irrigation canal near the river Śrī Hariñjing (nowadays Srinjing). This inscription is the last of its kind to be written using Pallava script; all consequent examples are written using Javanese script.

The 8th and 9th centuries are marked with the emergence of the Javanese literary tradition with Sang Hyang Kamahayanikan, a Buddhist treatise and the Kakawin Rāmâyaṇa , a Javanese rendering in Indian metres of the Vishnuistic Sanskrit epic, Rāmāyaṇa.

Although Javanese as a written language appeared considerably later than Malay (extant in the 7th century), the Javanese literary tradition is continuous from its inception to present day. The oldest works, such as the above mentioned Rāmāyaṇa, and a Javanese rendering of the Indian Mahabharata epic are studied assiduously today.

The expansion of the Javanese culture, including Javanese script and language, began in 1293 with the eastward push of the Hindu–Buddhist East-Javanese Empire Majapahit, toward Madura and Bali. The Javanese campaign in Bali in 1363 has had a deep and lasting impact. With the introduction of the Javanese administration, Javanese replaced Balinese as the language of administration and literature. Though the Balinese people preserved much of the older literature of Java and even created their own in Javanese idioms, Balinese ceased to be written until the 19th century.

See also: Kawi languageMiddle Javanese

The Majapahit Empire also saw the rise of a new language, Middle Javanese, which is an intermediate form between Old Javanese and New Javanese. In fact, Middle Javanese is so similar to New Javanese that works written in Middle Javanese should be easily comprehended by Modern Javanese speakers who are well acquainted with literary Javanese.

The Majapahit Empire fell due to internal disturbances in Paregreg civil war, thought to have occurred from 1405 to 1406, and attacks by Islamic forces of the Sultanate of Demak on the north coast of Java. There is a Javanese chronogram concerning the fall which reads, "sirna ilang krĕtaning bumi" ("vanished and gone was the prosperity of the world"), indicating the date AD 1478. Thus there is a popular belief that Majapahit collapsed in 1478, though it may have lasted into the 16th century. This was the last Hindu Javanese empire.

New Javanese

In the 16th century a new era in Javanese history began with the rise of the Islamic Central Javanese Mataram Sultanate, originally a vassal state of Majapahit. Ironically, the Mataram Empire rose as an Islamic kingdom which sought revenge for the demise of the Hindu Majapahit Empire by first crushing Demak, the first Javanese Islamic kingdom.

Javanese culture spread westward as Mataram conquered many previously Sundanese areas in western parts of Java; and Javanese became the dominant language in more than a third of this area. As in Bali, the Sundanese language ceased to be written until the 19th century. In the meantime it was heavily influenced by Javanese, and some 40% of Sundanese vocabulary is believed to have been derived from Javanese.

Though Islamic in name, the Mataram II empire preserved many elements of the older culture, incorporating them into the new religion. This is the reason why Javanese script is still in use as opposed to the writing of Old-Malay for example. After the Malays were converted, they dropped their form of indigenous writing and changed to a form of the "script of the Divine", the Arabic script.

In addition to the rise of Islam, the 16th century saw the emergence of the New Javanese language. The first Islamic documents in Javanese were already written in New Javanese, although still in antiquated idioms and with numerous Arabic loanwords. This is to be expected as these early New Javanese documents are Islamic treatises.

Later, intensive contacts with the Dutch and with other Indonesians gave rise to a simplified form of Javanese and influx of foreign loanwords.

Modern Javanese

Some scholars dub the spoken form of Javanese in the 20th century Modern Javanese, although it is essentially still the same language as New Javanese.

Javanese script

A modern bilingual text in Portuguese and Javanese in Yogyakarta.

A modern bilingual text in Portuguese and Javanese in Yogyakarta. Main article: Javanese script

Main article: Javanese scriptJavanese has been traditionally written with Javanese script. However, it has also be written with Arabic script and today generally uses Roman script. Javanese and anad the related Balinese script are modern variants of the old Kawi script, a Brahmic script introduced to Java along with Hinduism and Buddhism. Kawi is first attested in a legal document from 804 CE. It was widely used in literature and translations from Sanskrit from the tenth century; by the seventeenth, the script is identified as carakan. A Latin orthography based on Dutch was introduced in 1926, revised in 1972–1973, and has largely supplanted the carakan.

Majuscule Forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) A B C D E É È F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Minuscule Forms (also called lowercase or small letters) a b c d e é è f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z The letters f, q, v, x, and z are used in loanwords from European languages and Arabic.

Demographic distribution of Javanese speakers

See also: Javanese peopleJavanese is spoken throughout Indonesia, neighboring Southeast Asian countries, the Netherlands, Suriname, New Caledonia and other countries. However, the greatest concentration of speakers is found in the six provinces of Java itself, and in the neighboring Sumatran province of Lampung.

Below, a table with the number of native speakers in 1980 is provided.[9]

Indonesian province % of the pop. Javanese speakers (1980) 1. Aceh province 6.7% 175,000 2. North Sumatra 21.0% 1,757,000 3. West Sumatra 1.0% 56,000 4. Jambi 17.0% 245,000 5. South Sumatra 12.4% 573,000 6. Bengkulu 15.4% 118,000 7. Lampung 62.4% 2,886,000 8. Riau 8.5% 184,000 9. Jakarta 3.6% 236,000 10. West Java[10] 13.3% 3,652,000 11. Central Java 96.9% 24,579,000 12. Yogyakarta 97.6% 2,683,000 13. East Java 74.5% 21,720,000 14. Bali 1.1% 28,000 15. West Kalimantan 1.7% 41,000 16. Central Kalimantan 4.0% 38,000 17. South Kalimantan 4.7% 97,000 18. East Kalimantan 10.1% 123,000 19. North Sulawesi 1.0% 20,000 20. Central Sulawesi 2.9% 37,000 21. Southeast Sulawesi 3.6% 34,000 22. Maluku 1.1% 16,000 Based on the 1980 census, persons in approximately 43% of Indonesia's households spoke Javanese at home on a daily basis. By this reckoning there were well over 60 million Javanese speakers.[11] In 1980, the total number of the Indonesian population was 147,490,298.[12]

Above only 22 provinces of the then 27 provinces of Indonesia are taken. In each of these provinces, more than 1% of the population are Javanese speakers.

The distribution of persons living in Javanese-speaking households in East Java and Lampung requires clarification. For East Java, daily-language percentages are as follows: 74.5 Javanese; 23.0 Madurese; and 2.2 Indonesian. For Lampung, the official percentages are 62.4 Javanese; 16.4 Lampungese and other languages; 10.5 Sundanese and 9.4 Indonesian.

These figures are somewhat outdated for some regions, especially Jakarta while they remain more or less stable for the rest of Java. In Jakarta the number of Javanese has increased tenfold in the last 25 years. On the other hand, because of the conflict the number of Javanese in Aceh might have decreased. Furthermore it has to be noted that Banten has separated from West Java province in 2000.

Madurese in Javanese script

Madurese in Javanese script

In Banten, Western Java, the descendants of the Central Javanese conquerors who founded the Islamic Sultanate there in the 16th century still speak an archaic form of Javanese.[13] The rest of the population mainly speaks Sundanese and Indonesian as this province borders directly on Jakarta. Many commuters live in the Jakartan suburbs in Banten, among them also Javanese speakers. Their exact number is however unknown.

At least one third of the population of Jakarta is of Javanese descent and as such speak Javanese or have knowledge of it. In the province of West Java, many people speak Javanese, especially those living in the areas bordering Central Java, the cultural homeland of the Javanese.

The province of East Java is also home of the Madurese people, who number almost a quarter of the population (mostly on the Isle of Madura), but many Madurese actually have some knowledge of colloquial Javanese. Since the 19th century, Madurese was also written in the Javanese script. Unfortunately, the aspirated phonemes of Madurese are not reproduced in writing. The 19th century scribes apparently overlooked, or were ignorant of, the fact that Javanese script does possess these characters.

In Lampung the original inhabitants, the Lampungese, only make up some 15% of the population. The rest are the so-called "transmigrants", settlers from other parts of Indonesia, many as a result of past government transmigration programs. Most of these transmigrants are Javanese who have settled there since the 19th century.

In the former Dutch colony of Suriname (formerly called Dutch Guiana), in South America, approximately 15% of the population of some 500,000 are of Javanese descent, thus accounting for 75,000 speakers of Javanese. A local variant evolved, the "Tyoro Jowo-Suriname" or "Suriname Javanese".[14]

The Javanese language today

Although Javanese is not a national language, it has a recognised status as a regional language in three Indonesian provinces where the biggest concentrations of Javanese people are found, i.e. Central Java, Yogyakarta and East Java. Javanese is taught at schools and is also used in some mass media, both electronically and in print. There is, however, no longer a daily newspaper in Javanese. Some examples of Javanese language magazines include: Panjebar Semangat, Jaka Lodhang, Jaya Baya, Damar Jati, and Mekar Sari.

Since 2003, an East Java local television station (JTV) has broadcast some of its programmes in Surabayan dialect. Three such programmes are Pojok kampung (News), Kuis RT/RW and Pojok Perkoro (a criminal programme). Later on JTV also broadcast programmes in Central Javanese dialect which they call 'the western language' (basa kulonan) and Madurese.

In 2005, a new Javanese language magazine Damar Jati, saw its conception. The interesting fact is that, it is not published in the Javanese heartlands, but in Jakarta, the national capital of Indonesia.

Daily conversation

Javanese Ngoko: Piyé kabaré? Javanese Kromo: Pripun wartanipun panjenengan? Indonesian/Malay: Apa kabar? or Bagaimana kabar Anda? English: How are you? or How have you been?. Javanese Ngoko: Aku apik waé, piyé awakmu/sampèyan? Javanese Kromo: Kula saé kémawòn, pripun kalian panjenengan? Indonesian/Malay: Saya baik-baik saja, bagaimana dengan Anda? English: I am fine, how about you?. Javanese Ngoko: Sapa jenengmu? Javanese Kromo: Sinten asmanipun panjengenan? Indonesian/Malay: Siapa nama Anda? English: What is your name. Javanese Ngoko: Jenengku Jòhn Javanese Kromo: Nami kula Jòhn Indonesian/Malay: Nama saya John English: My name is John. Javanese Ngoko: Suwun/Matur nuwun Javanese Kromo: Matur sembah nuwun Indonesian/Malay: Terima kasih English: Thank you. Javanese Ngoko: Kowé arep ngombé apa? Javanese Kromo: Panjenengan kersa ngunjuk punapa? Indonesian/Malay: Anda mau minum apa? English: What do you want to drink?. Javanese Ngoko: Aku arep ngombé kòpi waé, Mas/Pak! Javanese Kromo: Kula badhé ngunjuk kòpi kémawòn, Pak! Indonesian/Malay: Saya ingin minum segelas kopi, Pak! English: I want to drink a glass of coffee, Sir!. Javanese Ngoko: Aku tresna karo kowé, Ndhuk! Javanese Kromo: Kula tresna kalian panjenengan, Nyi! Indonesian/Malay: Aku jatuh cinta padamu, Dik! English: I am falling in love with you, Lady!. Javanese: Witing tresna jalaran saka kulina (proverb) Indonesian/Malay: Cinta datang karena terbiasa English: Love comes from habit. Words

explanation: Javanese Ngoko is on the left and Javanese Krama is on the right

- yes = iya – inggih (nggih)

- no = ora – mboten

- what = apa – menapa

- who = sapa – sinten

- how = piyé/kepriyé – kadospundi/pripun

- why = ngapa – kenging menapa

- eat = mangan/maem – dahar/nedha

- sleep = turu – saré/bobok

- here = ning kéné – mriki

- there = ning kana – mrana

- there is (there are) = ana/ènèng – onten/wonten

- there is no (there are no) = ra ana/ra ènèng – mboten wonten

- no! I don't want it! = emoh/moh – wegah

- make a visit for pleasure = dolan – améng-améng

Numbers

Main article: Javanese numeralsJavanese Ngoko is on the left and Javanese Krama is on the right

- 1 = siji – setunggal

- 2 = loro – kalih

- 3 = telu – tiga

- 4 = papat – sekawan

- 5 = lima – gangsal

- 6 = enem – enem

- 7 = pitu – pitu

- 8 = wolu – wolu

- 9 = sanga – sanga

- 10 = sepuluh – sedasa

- 50 = séket – séket

- 100 = satus – setunggal atus

- hundreds = atusan – atusan

- 1000 = sewu – setunggal éwu

- thousands = éwon – éwon

See also

- Javanese literature

- Javanese script

- Java (island)

- Hans Ras

- Banyumasan language

- Johan Hendrik Caspar Kern

Footnotes

- ^ Van der Molen (1983:VII-VIII)

- ^ a b c d Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. Elsevier. 2008. p. 560. ISBN 0080877745, 9780080877747. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=F2SRqDzB50wC&pg=PA560&dq=%22javanese+phonology%22&cd=7#v=onepage&q=%22javanese%20phonology%22&f=false. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19814-8.

- ^ The Old Javanese spelling is modified to suit Modern Javanese spelling

- ^ Zoetmulder (1982:IX)

- ^ Uhlenbeck (1964:57)

- ^ a b Wolff, John U.; Soepomo Poedjosoedarmo (1982). Communicative Codes in Central Java. Cornell Southeast Asia Program. pp. 4. ISBN 0-87727-116-x.

- ^ For example Pigeaud's dictionary in 1939 is almost exclusively based on Surakarta speech (1939:viii-xiii)

- ^ The data is taken from the census of 1980 as provided by James J. Fox and Peter Gardiner and published by S.A. Wurm and Shiro Hattori, eds. 1983. Language Atlas of the Pacific Area, Part II. (Insular South-east Asia). Canberra

- ^ In 1980 this included the now separate Banten province

- ^ According James J. Fox and Peter Gardiner (Wurms and Hattori 1983)

- ^ Collins Concise Dictionary Plus (1989)

- ^ Pigeaud (1967:10-11)

- ^ Bartje S. Setrowidjojo and Ruben T. Setrowidjojo Het Surinaams-Javaans = Tyoro Jowo-Suriname, Den Haag : Suara Jawa, 1994, ISBN 90-802125-1-2

Sources

- Elinor C. Horne. 1961. Beginning Javanese. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- W. van der Molen. 1993. Javaans schrift. Leiden: Vakgroep Talen en Culturen van Zuidoost-Azië en Oceanië. ISBN 90-73084-09-1

- S.A. Wurm and Shiro Hattori, eds. 1983. Language Atlas of the Pacific Area, Part II. (Insular South-east Asia). Canberra.

- P.J. Zoetmulder. 1982. Old Javanese–English Dictionary. 's-Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 90-247-6178-6

External links

Categories:- Javanese language

- Languages of Malaysia

- Languages of Indonesia

- Languages of Suriname

- Agglutinative languages

- SVO languages

- Malayo-Polynesian

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.