- Triage

-

This article is about the concept of triage as it occurs in medical emergencies and disasters. For other uses, see Triage (disambiguation).

Triage (

/ˈtriːɑːʒ/ (UK English) or triːˈɑːʒ (US English)) is the process of determining the priority of patients' treatments based on the severity of their condition. This rations patient treatment efficiently when resources are insufficient for all to be treated immediately. The term comes from the French verb trier, meaning to separate, sift or select.[1] Two types of triage exist: simple and advanced.[2] Triage may result in determining the order and priority of emergency treatment, the order and priority of emergency transport, or the transport destination for the patient.

/ˈtriːɑːʒ/ (UK English) or triːˈɑːʒ (US English)) is the process of determining the priority of patients' treatments based on the severity of their condition. This rations patient treatment efficiently when resources are insufficient for all to be treated immediately. The term comes from the French verb trier, meaning to separate, sift or select.[1] Two types of triage exist: simple and advanced.[2] Triage may result in determining the order and priority of emergency treatment, the order and priority of emergency transport, or the transport destination for the patient.Triage may also be used for patients arriving at the emergency department, or to telephone medical advice systems,[3] among others. This article deals with the concept of triage as it occurs in medical emergencies, including the prehospital setting, disasters, and during emergency room treatment.

Triage originated in World War I by French doctors treating the battlefield wounded at the aid stations behind the front. Much is owed to the work of Dominique Jean Larrey during the Napoleonic Wars. Until recently, triage results, whether performed by a paramedic or anyone else, were frequently a matter of the 'best guess', as opposed to any real or meaningful assessment.[4] At its most primitive, those responsible for the removal of the wounded from a battlefield or their care afterwards have divided victims into three categories:

- Those who are likely to live, regardless of what care they receive;

- Those who are likely to die, regardless of what care they receive;

- Those for whom immediate care might make a positive difference in outcome.[5]

For many emergency medical services (EMS) systems, a similar model can sometimes still be applied. However once a full response has occurred and many hands are available, paramedics will usually use the model included in their service policy and standing orders. In the earliest stages of an incident, however, when one or two paramedics exist to twenty or more patients, practicality demands that the above, more "primitive" model will be used.

Modern approaches to triage are more scientific. The outcome and grading of the victim is frequently the result of physiological and assessment findings. Some models, such as the START model, are committed to memory, and may even be algorithm-based. As triage concepts become more sophisticated, triage guidance is also evolving into both software and hardware decision support products for use by caregivers in both hospitals and the field.[6]

Contents

Types of triage

Simple triage

Simple triage is usually used in a scene of an accident or "mass-casualty incident" (MCI), in order to sort patients into those who need critical attention and immediate transport to the hospital and those with less serious injuries. This step can be started before transportation becomes available. The categorization of patients based on the severity of their injuries can be aided with the use of printed triage tags or coloured flagging.[7]

S.T.A.R.T. model

S.T.A.R.T. (Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment) is a simple triage system that can be performed by lightly trained lay and emergency personnel in emergencies.[8] It is not intended to supersede or instruct medical personnel or techniques. It has been (2003) taught to California emergency workers for use in earthquakes. It was developed at Hoag Hospital in Newport Beach, California for use by emergency services. It has been field-proven in mass casualty incidents such as train wrecks and bus accidents, though it was developed for use by community emergency response teams (CERTs) and firefighters after earthquakes.

Triage separates the injured into four groups:

- The expectant who are beyond help

- The injured who can be helped by immediate transportation

- The injured whose transport can be delayed

- Those with minor injuries, who need help less urgently

Advanced triage

In advanced triage, doctors may decide that some seriously injured people should not receive advanced care because they are unlikely to survive. Advanced care will be used on patients with less severe injuries. Because treatment is intentionally withheld from patients with certain injuries, advanced triage has ethical implications. It is used to divert scarce resources away from patients with little chance of survival in order to increase the chances of survival of others who are more likely to survive.

In Western Europe, the criterion used for this category of patient is a trauma score of consistently at or below 3. This can be determined by using the Triage Revised Trauma Score (TRTS), a medically-validated scoring system incorporated in some triage cards.[9]

Another example of a trauma scoring system is the Injury Severity Score (ISS). This assigns a score from 0 to 75 based on severity of injury to the human body divided into three categories: A (face/neck/head), B(thorax/abdomen), C(extremities/external/skin). Each category is scored from 0 to 5 using the Abbreviated Injury Scale, from uninjured to critically injured, which is then squared and summed to create the ISS. A score of 6, for "unsurvivable", can also be used for any of the three categories, and automatically sets the score to 75 regardless of other scores. Depending on the triage situation, this may indicate either that the patient is a first priority for care, or that he or she will not receive care owing to the need to conserve care for more likely survivors.

The use of advanced triage may become necessary when medical professionals decide that the medical resources available are not sufficient to treat all the people who need help. The treatment being prioritized can include the time spent on medical care, or drugs or other limited resources. This has happened in disasters such as volcanic eruptions, thunderstorms, and rail accidents. In these cases some percentage of patients will die regardless of medical care because of the severity of their injuries. Others would live if given immediate medical care, but would die without it.

In these extreme situations, any medical care given to people who will die anyway can be considered to be care withdrawn from others who might have survived (or perhaps suffered less severe disability from their injuries) had they been treated instead. It becomes the task of the disaster medical authorities to set aside some victims as hopeless, to avoid trying to save one life at the expense of several others.

If immediate treatment is successful, the patient may improve (although this may be temporary) and this improvement may allow the patient to be categorized to a lower priority in the short term. Triage should be a continuous process and categories should be checked regularly to ensure that the priority remains correct. A trauma score is invariably taken when the victim first comes into hospital and subsequent trauma scores taken to see any changes in the victim's physiological parameters. If a record is maintained, the receiving hospital doctor can see a trauma score time series from the start of the incident, which may allow definitive treatment earlier.

- Typical triaging systems

Continuous integrated triage

Continuous Integrated Triage is an approach to triage in mass casualty situations which is both efficient and sensitive to psychosocial and disaster behavioral health issues that affect the number of patients seeking care (surge), the manner in which a hospital or healthcare facility deals with that surge (surge capacity)[10] and the overarching medical needs of the event.

Continuous Integrated Triage combines three forms of triage with progressive specificity to most rapidly identify those patients in greatest need of care while balancing the needs of the individual patients against the available resources and the needs of other patients. Continuous Integrated Triage employs:

- Group (Global) Triage (i.e., M.A.S.S. triage)[11]

- Physiologic (Individual) Triage (i.e., S.T.A.R.T.)

- Hospital Triage (i.e., E.S.I. or Emergency Severity Index)

However any Group, Individual and/or Hospital Triage system can be used at the appropriate level of evaluation.

Practical applied triage

During the early stages of an incident, first responders may be overwhelmed by the scope of patients and injuries. One valuable technique, is the Patient Assist Method (PAM); the responders quickly establish a casualty collection point (CCP) and advise ; either by yelling, or over a loudspeaker, that "anyone requiring assistance should move to the selected area (CCP)". This does several things at once, it identifies patients that are not so severely injured, that they need immediate help, it physically clears the scene, and provides possible assistants to the responders. As those who can move, do so, the responders then ask, "anyone who still needs assistance, yell out or raise your hands"; this further identifies patients who are responsive, yet maybe unable to move. Now the responders can rapidly assess the remaining patients who are either expectant, or are in need of immediate aid. From that point the first responder is quickly able to identify those in need of immediate attention, while not being distracted or overwhelmed by the magnitude of the situation. Using this method assumes the ability to hear. Deaf, partially deaf or victims of a large blast injury may not be able to hear these instructions.

Reverse triage

In addition to the standard practices of triage as mentioned above, there are conditions where sometimes the less wounded are treated in preference to the more severely wounded. This may arise in a situation such as war where the military setting may require soldiers be returned to combat as quickly as possible, or disaster situations where medical resources are limited in order to conserve resources for those likely to survive but requiring advanced medical care.[12] Other possible scenarios where this could arise include situations where significant numbers of medical personnel are among the affected patients where it may be advantageous to ensure that they survive to continue providing care in the coming days especially if medical resources are already stretched. In cold water drowning incidents, it is common to use reverse triage because drowning victims in cold water can survive longer than in warm water if given immediate basic life support and often those who are rescued and able to breathe on their own will improve with minimal or no help.[13]

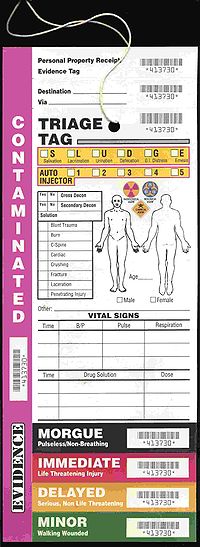

Labelling of patients

Upon completion of the initial assessment by medical or paramedical personnel, each patient will be labelled with a device called a triage tag. This will identify the patient and any assessment findings and will identify the priority of the patient's need for medical treatment and transport from the emergency scene. Triage tags may take a variety of forms. Some countries use a nationally standardized triage tag,[14] while in other countries commercially available triage tags are used, and these will vary by jurisdictional choice.[15] The most commonly used commercial systems include the METTAG,[16] the SMARTTAG,[17] E/T LIGHT tm[18] and the CRUCIFORM systems.[19] More advanced tagging systems incorporate special markers to indicate whether or not patients have been contaminated by hazardous materials, and also tear off strips for tracking the movement of patients through the process. Some of these tracking systems are beginning to incorporate the use of handheld computers, and in some cases, bar code scanners. At its most primitive, however, patients may be simply marked with coloured tape, or with marker pens, when triage tags are either unavailable or insufficient.

Undertriage and overtriage

Undertriage is the process of underestimating the severity of an illness or injury. An example of this would be categorizing a Priority 1 (Immediate) patient as a Priority 2 (Delayed) or Priority 3 (Minimal). Historically, acceptable undertriage rates have been deemed 5% or less. Overtriage is the process of overestimating the level to which an individual has experienced an illness or injury. An example of this would be categorizing a Priority 3 (Minimal) patient as a Priority 2 (Delayed) or Priority 1 (Immediate). Acceptable overtriage rates have been typically up to 50% in an effort to avoid undertriage. Some studies suggest that overtriage is less likely to occur when triaging is performed by hospital medical teams, rather than paramedics or EMTs.[20]

Regional variation

United States military

Triage in a non-combat situation is conducted much the same as in civilian medicine. A battlefield situation, however, requires medics and corpsmen to rank casualties for precedence in MEDEVAC or CASEVAC. The triage categories (with corresponding color codes), in precedence, are:

- Immediate: The casualty requires immediate medical attention and will not survive if not seen soon. Any compromise to the casualty's respiration, hemorrhage control, or shock control could be fatal.

- Delayed: The casualty requires medical attention within 6 hours. Injuries are potentially life-threatening, but can wait until the Immediate casualties are stabilized and evacuated.

- Minimal: "Walking wounded," the casualty requires medical attention when all higher priority patients have been evacuated, and may not require stabilization or monitoring.

- Expectant: The casualty is expected not to reach higher medical support alive without compromising the treatment of higher priority patients. Care should not be abandoned, spare any remaining time and resources after Immediate and Delayed patients have been treated.[21]

Afterwards, casualties are given an evacuation priority based on need:

- Urgent: evacuation is required within two hours to save life or limb.

- Priority: evacuation is necessary within four hours or the casualty will deteriorate to "Urgent".

- Routine: evacuate within 24 hours to complete treatment.

In a "naval combat situation", the triage officer must weigh the tactical situation with supplies on hand and the realistic capacity of the medical personnel. This process can be ever-changing, dependent upon the situation and must attempt to do the maximum good for the maximum number of casualties.[22]

Field assessments are made by two methods: primary survey (used to detect & treat life-threatening injuries) and secondary survey (used to treat non-life threatening injuries) with the following categories:

- Class I Patients who require minor treatment and can return to duty in a short period of time.

- Class II Patients whose injuries require immediate life sustaining measures.

- Class III Patients for whom definitive treatment can be delayed without loss of life or limb.

- Class IV Patients requiring such extensive care beyond medical personnel capability and time.

Canada

In the mid-1980s, The Victoria General Hospital, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, introduced paramedic triage in its Emergency Department. Unlike all other centres in North America that employ physician and primarily nurse triage models, this hospital began the practice of employing Primary Care level paramedics to perform triage upon entry to the Emergency Department. In 1997, following the amalgamation of two of the city's largest hospitals, the Emergency Department at the Victoria General closed. The paramedic triage system was moved to the city's only remaining adult emergency department, located at the New Halifax Infirmary. In 2006, a triage protocol on whom to exclude from treatment during a flu pandemic was written by a team of critical-care doctors at the behest of the Ontario government.

For routine emergencies, many locales in Canada now employ the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) for all incoming patients.[23] The system categorizes patients by both injury and physiological findings, and ranks them by severity from 1-5. The model is used by both paramedics and E/R nurses, and also for pre-arrival notifications in some cases. The model provides a common frame of reference for both nurses and paramedics, although the two groups do not always agree on scoring. It also provides a method, in some communities, for benchmarking the accuracy of pre-triage of calls using AMPDS (What percentage of emergency calls have return priorities of CTAS 1,2,3, etc.) and these findings are reported as part of a municipal performance benchmarking initiative in Ontario. Curiously enough the model is not currently used for mass casualty triage, and is replaced by the START protocol and METTAG triage tags.[24]

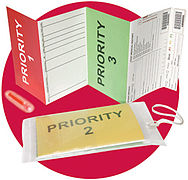

United Kingdom

In the UK, the commonly used triage system is the Smart Incident Command System,[25] taught on the MIMMS (Major Incident Medical Management (and) Support) training program.[26] The UK Armed Forces are also using this system on operations worldwide. This grades casualties from Priority 1 (most urgent) to Priority 4 (expectant, i.e. likely to die).[27]

In the UK and Europe, the triage process used is sometimes similar to that of the United States, but the categories are different:[28]

- Dead - patients who have a trauma score of 0 to 2 and are beyond help

- Immediate - patients who have a trauma score of 3 to 10 (RTS) and need immediate attention

- Urgent - patients who have a trauma score of 10 or 11 and can wait for a short time before transport to definitive medical attention

- Delayed - patients who have a trauma score of 12 (maximum score) and can be delayed before transport from the scene

Finland

Triage at an accident scene is performed by a paramedic or an emergency physician, using the four-level scale of Cannot wait, Has to wait, Can wait and Lost.

France

In France, the Prehospital triage in case of a disaster uses a four-level scale:

- DCD: décédé (deceased), or urgence dépassée (beyond urgency)

- UA: urgence absolue (absolute urgency)

- UR: urgence relative (relative urgency)

- UMP: urgence médico-psychologique (medical-psychological urgency) or impliqué (implied, i.e. lightly wounded or just psychologically shocked).

This triage is performed by a physician called médecin trieur (sorting medic).[29] This triage is usually performed at the field hospital (PMA–poste médical avancé, i.e. forward medical post). The absolute urgencies are usually treated onsite (the PMA has an operating room) or evacuated to a hospital. The relative urgencies are just placed under watch, waiting for an evacuation. The involved are addressed to another structure called the CUMP–Cellule d'urgence médico-psychologique (medical-psychological urgency cell); this is a resting zone, with food and possibly temporary lodging, and a psychologist to take care of the brief reactive psychosis and avoid post-traumatic stress disorder.

In the emergency room of a hospital, the triage is performed by a physician called MAO–médecin d'accueil et d'orientation (reception and orientation physician), and a nurse called IOA– infirmière d'organisation et d'accueil (organisation and reception nurse). Some hospitals and SAMU organisations now use the "Cruciform" card referred to elsewhere.

France has also a Phone Triage system for Medical Emergencies Phone Demands in its Samu Medical Regulation Centers through the 15 medical free national hot line. "Medical Doctor Regulator" decides what is to be the most efficient solution = Emergency Telemedecine or dispatch of an Ambulance, a General Practitioner or a Physician+ Nurse + Ambulance Man, Hospital based MICU (Mobile Intensive Care Unit).

Germany

Preliminary assessment of injuries is usually done by the first ambulance crew on scene, with this role being assumed by the first Notarzt arriving at the scene. As a rule, there will be no cardiopulmonary resuscitation, so patients who do not breathe on their own or develop circulation after their airways are cleared, will be tagged "deceased". Also, not every major injury automatically qualifies for a red tag. A patient with a traumatic amputation of the forearm might just be tagged yellow, have the bleeding stopped, and then be sent to a hospital when possible. After the preliminary assessment, a more specific and definite triage will follow, as soon as patients are brought to a field treatment facility. There, they will be disrobed and fully examined by an emergency physician. This will take approximately 90 seconds per patient.[30]

The German triage system also uses four, sometimes five colour codes to denote the urgency of treatment.[31] Typically, every ambulance is equipped with a folder or bag with coloured ribbons or triage tags. The urgency is denoted as follows:

Category Meaning Consequences Examples T1 (I) Acute danger for life Immediate treatment, transport as soon as possible Arterial lesions, internal haemorrhage, major amputations T2 (II) Severe injury Constant observation and rapid treatment, transport as soon as practical Minor amputations, flesh wounds, fractures and dislocations T3 (III) Minor injury or no injury Treatment when practical, transport and/or discharge when possible Minor lacerations, sprains, abrasions T4 (IV) No or small chance of survival Observation and if possible administration of analgesics Severe injuries, uncompensated blood loss, negative neurological assessment T5 (V) Deceased Collection and guarding of bodies, identification when possible Dead on arrival, downgraded from T1-4, no spontaneous breathing after clearing of airway Israel

A simplified description of the S.T.A.R.T. is taught in the Israeli army to non-medical personnel: the injured who are lying on the ground silently should be prepared for immediate transportation; injured lying on the ground but screaming are injured whose transportation can be delayed; and the walking wounded need help less urgently.[32] Non-medical personnel have no authority to tag an injured person as deceased.

Japan

In Japan, the triage system is mainly used by health professionals. The categories of triage, in corresponding color codes, are:

- Category I: Used for viable victims with potentially life threatening conditions.

- Category II: Used for victims with non-life threatening injuries, but who urgently require treatment.

- Category III: Used for victims with minor injuries that do not require ambulance transport.

- Category 0: Used for victims who are dead, or whose injuries make survival unlikely.

Triage outcomes

Evacuation

Simple triage identifies which people need advanced medical care. In the field, triage also sets priorities for evacuation to hospitals.[33] In S.T.A.R.T., casualties should be evacuated as follows:

- Deceased are left where they fell, covered if necessary; note that in S.T.A.R.T. a person is not triaged "deceased" unless they are not breathing and an effort to reposition their airway has been unsuccessful.

- Immediate or Priority 1 (red) evacuation by MEDEVAC if available or ambulance as they need advanced medical care at once or within 1 hour. These people are in critical condition and would die without immediate assistance.

- Delayed or Priority 2 (yellow) can have their medical evacuation delayed until all immediate persons have been transported. These people are in stable condition but require medical assistance.

- Minor or Priority 3 (green) are not evacuated until all immediate and delayed persons have been evacuated. These will not need advanced medical care for at least several hours. Continue to re-triage in case their condition worsens. These people are able to walk, and may only require bandages and antiseptic.

Alternative care facilities

Alternative care facilities are places that are set up for the care of large numbers of patients, or are places that could be so set up. Examples include schools, sports stadiums, and large camps that can be prepared and used for the care, feeding, and holding of large numbers of victims of a mass casualty or other type of event.[34] Such improvised facilities are generally developed in cooperation with the local hospital, which sees them as a strategy for creating surge capacity. While hospitals remain the preferred destination for all patients, during a mass casualty event such improvised facilities may be required in order to divert low-acuity patients away from hospitals in order to prevent the hospitals becoming overwhelmed.

Secondary (in-hospital) triage

In advanced triage systems, secondary triage is typically implemented by paramedics, battlefield medical personnel or by skilled nurses in the emergency departments of hospitals during disasters, injured people are sorted into five categories.[35]

- Black / Expectant: They are so severely injured that they will die of their injuries, possibly in hours or days (large-area burns, severe trauma, lethal radiation dose), or in life-threatening medical crisis that they are unlikely to survive given the care available (cardiac arrest, septic shock, severe head or chest wounds); they should be taken to a holding area and given painkillers as required to reduce suffering.

- Red / Immediate: They require immediate surgery or other life-saving intervention, and have first priority for surgical teams or transport to advanced facilities; they "cannot wait" but are likely to survive with immediate treatment.

- Yellow / Observation: Their condition is stable for the moment but requires watching by trained persons and frequent re-triage, will need hospital care (and would receive immediate priority care under "normal" circumstances).

- Green / Wait (walking wounded): They will require a doctor's care in several hours or days but not immediately, may wait for a number of hours or be told to go home and come back the next day (broken bones without compound fractures, many soft tissue injuries).

- White / Dismiss (walking wounded):They have minor injuries; first aid and home care are sufficient, a doctor's care is not required. Injuries are along the lines of cuts and scrapes, or minor burns.

Some crippling injuries, even if not life-threatening, may be elevated in priority based on the available capabilities. During peacetime, most amputations may be triaged "Red" because surgical reattachment must take place within minutes, even though in all probability the person will not die without a thumb or hand.

Hospital triage systems in the United States

Within the hospital system, the first stage on arrival at the emergency room is assessment by the hospital triage nurse. This nurse will evaluate the patient's condition, as well as any changes, and will determine their priority for admission to the Emergency Room and also for treatment.[36] Once emergency assessment and treatment are complete, the patient may need to be referred to the hospital's internal triage system.

For a typical inpatient hospital triage system, a triage physician will either field requests for admission from the ER physician on patients needing admission or from physicians taking care of patients from other floors who can be transferred because they no longer need that level of care (i.e. intensive care unit patient is stable for the medical floor). This helps keep patients moving through the hospital in an efficient and effective manner.

This triage position is often done by a hospitalist. A major factor contributing to the triage decision is available hospital bed space. The triage hospitalist must determine, in conjunction with a hospital's "bed control" and admitting team, what beds are available for optimal utilization of resources in order to provide safe care to all patients. A typical surgical team will have their own system of triage for trauma and general surgery patients. This is also true for neurology and neurosurgical services. The overall goal of triage, in this system, is to both determine if a patient is appropriate for a given level of care and to ensure that hospital resources are utilized effectively.

Bioethical implications in triage

Bioethical concerns have historically played an important role in triage decisions, such as the allocation of iron lungs during the polio epidemics of the 1940s and of dialysis machines during the 1960s.[37] As many health care systems in the developed world continue to plan for an expected influenza pandemic, bioethical issues regarding the triage of patients and the rationing of care continue to evolve. Similar issues may occur for paramedics in the field in the earliest stages of mass casualty incidents when large numbers of potentially serious or critical patients may be combined with extremely limited staffing and treatment resources.

Ventilator rationing

In a potential influenza pandemic, it is anticipated that, as hospitals and treatment centers become overwhelmed, shortages of critical equipment such as ventilators will occur. Medications may run short. Supply chains may fail. Methods will be required for determining who will receive access to life saving technologies, and who will not. For example, if a hypothetical emergency department has all three of its ventilators currently in use for elderly patients with influenza, who will not survive without them, how should it act when paramedics arrive with a forty year old, otherwise healthy patient who is being ventilated due to influenza, but for whom no hospital ventilator is available. A similar concern arises as to whether long-term patients in chronic care facilities should be removed from life-support to provide their ventilators to acutely ill influenza patients.[37]

A New York State Workgroup headed by psychiatrist Tia Powell proposed guidelines for such triage in 1997.[38][39] The Workgroup excluded certain groups of patients from eligibility for life support during a pandemic: those with metastatic cancer, severe brain damage, multiple cardiac arrests and organ failure. Among those excluded were dialysis patients. Bioethicist Jacob Appel of New York University has questioned the automatic exclusion of dialysis patients and also the WorkGroup's decision not to include nursing home ventilators among those machines available for triage.[40] Emergency medicine expert Art Kellerman of Emory University has argued that "[t]his kind of thinking, as scary or even horrifying as it may seem, is absolutely critical and is much better done now than on the fly in the middle of a pandemic."[39]

Research continues into alternative care, and various centers propose medical decision-support models for such situations.[41] Some of these models are purely ethical in origin, while others attempt to use other forms of clinical classification of patient condition as a method of standardized triage.[42]

See also

- Battlefield medicine

- Combat stress reaction

- Field Triage

- First aid

- Hospital emergency codes

- Mass decontamination

- Mental health triage - brief overview of the Australian concept for dealing with psychiatric emergencies, similar to physical triage.

- Remote Physiological Monitoring

- Wilderness first aid

References

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/triage. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/triage. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ "NHS Direct website". http://www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk/. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ Iserson KV, Moskop JC (March 2007). "Triage in medicine, part I: Concept, history, and types". Ann Emerg Med 49 (3): 275–81. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.05.019. PMID 17141139.

- ^ Chipman M, Hackley BE, Spencer TS (February 1980). "Triage of mass casualties: concepts for coping with mixed battlefield injuries". Mil Med 145 (2): 99–100. PMID 6768037.

- ^ "Transforming Triage Technology (National Research Council of Canada website)". http://www.nrccnrc.gc.ca/highlights/2006/0606triage_e.html. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ "Webster's ONline Dictionary". http://www.websters-online-dictionary.org/tr/triage.html. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ Burstein, Jonathan L.; Hogan, David (2007). Disaster medicine. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 25. ISBN 0-7817-6262-6.

- ^ "The Field Triage (European Trauma Course)". http://www-cdu.dc.med.unipi.it/ECTC/etria.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ "Medical Surge Capacity and Capability". Archived from the original on 2008-07-14. http://web.archive.org/web/20080714194322/http://www.cna.org/documents/mscc_aug2004.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ "National Disaster Life Support Foundation website". http://www.ndlsf.org/common/content.asp?PAGE=347. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ "Military Triage". http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/431314_2. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Elixson EM (June 1991). "Hypothermia. Cold-water drowning". Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 3 (2): 287–92. PMID 2054134.

- ^ Idoguchi K, Mizobata Y, et al. (2006). "Usefulness of Our Proposed Format of Triage Tag". Journal of Japanese Association for Acute Medicine 17 (5): 183–191. http://sciencelinks.jp/j-east/article/200615/000020061506A0519176.php.

- ^ Nocera A, (Winter 2000). "Australian disaster triage: a colour maze in the Tower of Babel". Australian Journal of Emergency Management: 35–40. http://www.ema.gov.au/www/emaweb/rwpattach.nsf/VAP/(084A3429FD57AC0744737F8EA134BACB)~Australian_disaster_triage.pdf/$file/Australian_disaster_triage.pdf.

- ^ "METTAG Corporate website". http://www.mettag.com/. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ "Smart Triage Tag, (TSG Associates Corporate website". http://www.tsgassociates.co.uk/English/Civilian/products/smart_tag.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ Beidel, Eric (December 2010). "Military Medics, First Responders Guided By Simple Light". nationaldefensemagazine.org. http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/archive/2010/December/Pages/MilitaryMedics,FirstRespondersGuidedBySimpleLight.aspx.

- ^ Lakha, Raj; Tony Moore (2006). Tolley's handbook of disaster and emergency management. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 0-7506-6990-X.

- ^ Turegano-Fuentes F, Perez-Diaz D et al. (2008). "Overall Assessment of the Response to Terrorist Bombings in Trains, Madrid, 11 March 2004". European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 34 (5): 433–441. doi:10.1007/s00068-008-8805-2.

- ^ "US Army Study Guide". http://www.armystudyguide.com/content/powerpoint/First_Aid_Presentations/triage-2.shtml. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Koehler RH, Smith RS, Bacaner T (August 1994). "Triage of American combat casualties: the need for change". Mil Med 159 (8): 541–7. PMID 7824145.

- ^ "Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians website)". http://www.caep.ca/template.asp?id=B795164082374289BBD9C1C2BF4B8D32. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ "METTAG Triage Tags". http://www.mettag.com/. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ TSGassociates.co.uk

- ^ "Major Incident Medical Management and Support Course". http://www.health.wa.gov.au/disaster/docs/Registration_Form_3.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Ryan J; Pérez-Díaz, Dolores; Sanz-Sánchez, Mercedes; Ortiz Alonso, Javier (2008). "Triage: Principles and Pressures". European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery 34 (5): 427–432. doi:10.1007/s00068-008-8805-2.

- ^ Jill Windle; Manchester Triage Group Staff; Mackway-Jones, Kevin; Marsden, Janet (2006). Emergency triage. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 0-7279-1542-8.

- ^ David L. Hoyt; Wilson, William J.; Grande, Christopher M. (2007). Trauma. Informa Healthcare. ISBN 0-8247-2919-6.

- ^ "Telemedical support of emergency prehospital care in mass casualty incidents". http://www.umi.cs.tu-bs.de/full/research/med_tel/notfall/dokumente/MCI_DLR.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-04.

- ^ Beck A, Bayeff-Filloff M, Bischoff M, Schneider BM (November 2002). "[Analysis of the incidence and causes of mass casualty events in a southern Germany medical rescue area]" (in German). Unfallchirurg 105 (11): 968–73. doi:10.1007/s00113-002-0516-2. PMID 12402122.

- ^ "Magen David Adom: The EMS Israeli Experience". http://www.cdphe.state.co.us/epr/Public/HPP/ROCKYM.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ "Code Orange Plan (Assiniboine Regional Health Authority)". http://www.assiniboine-rha.ca/Disaster%20Plan%20new%20June%2008/2/CODE%20Info/Orange/CODE%20ORANGE_arha_04.pdf. Retrieved 2008-12-05.[dead link]

- ^ "Chapter 8: Clinical and Public Health Systems Issues Arising from the Outbreak of Sars in Toronto (Public Health Agency of Canada website)". http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/sars-sras/naylor/8-eng.php. Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ Mehta S (April 2006). "Disaster and mass casualty management in a hospital: How well are we prepared?". J Postgrad Med 52 (2). https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/6941/1/jp06028.pdf.

- ^ Slater RR (January 1970). "Triage nurse in the emergency department". Am J Nurs (Lippincott Williams &) 70 (1): 127–9. doi:10.2307/3421031. JSTOR 3421031. PMID 5196143.

- ^ a b The Coming Ethical Crisis: Oxygen Rationing

- ^ Guidelines

- ^ a b Cornelia Dean, Guidelines for Epidemics: Who Gets a Ventilator?, The New York Times, March 25, 2008

- ^ Appel, Jacob. The Coming Ethical Crisis: Oxygen Rationing June 26, 2009

- ^ "Who dies, who doesn't: docs decide flu pandemic guidelines (CBC News Item)". 2006-11-21. http://www.cbc.ca/health/story/2006/11/20/pandemic-triage.html. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

- ^ Christian MD, Hawryluck L, Wax RS, et al. (November 2006). "Development of a triage protocol for critical care during an influenza pandemic". CMAJ 175 (11): 1377–81. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060911. PMC 1635763. PMID 17116904. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1635763.

Health science > Medicine > Emergency medicine Procedures Acute Care of at-Risk Newborns (ACoRN) · Advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) · Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) · Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) · First aid · Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) · Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) · Basic Life SupportEquipment Bag valve mask (BVM) · Chest tube · Defibrillation (AED, ICD) · Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG) · Intraosseous infusion (IO) · Intravenous therapy (IV) · Tracheal intubation · Nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) · Oropharyngeal airway (OPA) · Pocket maskDrugs Other Emergency medical services around the world Emergency medical services by country Austria · Australia · Canada · France · Germany · Hong Kong · Iceland · Ireland · Israel · Italy · Netherlands · New Zealand · Norway · Poland · Portugal · Spain · South Africa · Sri Lanka · United Kingdom · United StatesParamedics by country Categories:- Triage

- French medical phrases

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.