- Josephine Baker

-

For the first female Director of Public Health, see Sara Josephine Baker.

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker in Havana, Cuba (1950)Background information Birth name Freda Josephine McDonald Born June 3, 1906, St. Louis, Missouri, U.S.[1][2] Died April 12, 1975 (aged 68), Paris, France Genres Cabaret, Music hall, French pop, French jazz Occupations Dancer, singer, actress Instruments Vocals Years active 1921–1975 Labels Columbia, Mercury, RCA Victor Website Josephine Baker profile Josephine Baker (June 3, 1906 – April 12, 1975) was an American dancer, singer, and actress who found fame in her adopted homeland of France. She was given such nicknames as the "Bronze Venus", the "Black Pearl", and the "Créole Goddess".

Baker was the first African American female to star in a major motion picture, to integrate an American concert hall, and to become a world-famous entertainer. She is also noted for her contributions to the Civil Rights Movement in the United States (she was offered the unofficial leadership of the movement by Coretta Scott King in 1968 following Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination, but turned it down),[3] for assisting the French Resistance during World War II,[4] and for being the first American-born woman to receive the French military honor, the Croix de guerre.

Contents

Early life

Baker was born Freda Josephine McDonald in St. Louis, Missouri,[1][2] the daughter of Carrie McDonald. Her estate identifies vaudeville drummer Eddie Carson as her natural father.[5] A biography written by her foster son Jean-Claude Baker stated:

“ … (Josephine Baker's) father was identified (on the birth certificate) simply as "Edw" … I think Josephine's father was white—so did Josephine, so did her family … people in St. Louis say that (Josephine's mother) had worked for a German family (around the time she became pregnant). (Carrie) let people think Eddie Carson was the father, and Carson played along … (but) Josephine knew better.[6] ” Her mother, Carrie, was adopted in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1886 by Richard and Elvira McDonald, both of whom were former slaves of African and Native American descent.[6] When Baker was eight she was sent to work for a white woman who abused her, burning Baker's hands when she put too much soap in the laundry. She later went to work for another woman.

Baker dropped out of school at the age of 12 and lived as a street child in the slums of St. Louis, sleeping in cardboard shelters and scavenging for food in garbage cans.[7] Her street-corner dancing attracted attention and she was recruited for the St. Louis Chorus vaudeville show at 15. She then headed to New York City during the Harlem Renaissance, performing at the Plantation Club and in the chorus of the popular Broadway revues Shuffle Along (1921) with Adelaide Hall and The Chocolate Dandies (1924). She performed as the last dancer in a chorus line, a position in which the dancer traditionally performed in a comic manner, as if she was unable to remember the dance, until the encore, at which point she would not only perform it correctly, but with additional complexity. Baker was then billed as "the highest-paid chorus girl in vaudeville".[citation needed]

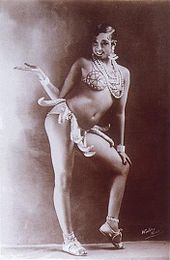

On October 2, 1925, she opened in Paris at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, where she became an instant success for her erotic dancing and for appearing practically nude on stage. After a successful tour of Europe, she reneged on her contract and returned to France to star at the Folies Bergères, setting the standard for her future acts. She performed the Danse sauvage, wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas. Her success coincided (1925) with the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs, which gave birth to the term "Art Deco", and also with a renewal of interest in ethnic forms of art, including African. Baker represented one aspect of this fashion. In later shows in Paris she was often accompanied on stage by her pet cheetah, Chiquita, who was adorned with a diamond collar. The cheetah frequently escaped into the orchestra pit, where it terrorized the musicians, adding another element of excitement to the show.[citation needed]

Rise to fame

After a short while she was the most successful American entertainer working in France. Ernest Hemingway called her "… the most sensational woman anyone ever saw."[8][9] In addition to being a musical star, Baker also starred in three films which found success only in Europe: the silent film Siren of the Tropics (1927), Zouzou (1934) and Princesse Tam Tam (1935). She also starred in Fausse Alerte (English title: The French Way) in 1940.

At this time she also scored her most successful song, "J'ai deux amours" (1931) and became a muse for contemporary authors, painters, designers, and sculptors including Langston Hughes, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Pablo Picasso, and Christian Dior. Under the management of Giuseppe Pepito Abatino — a Sicilian former stonemason who passed himself off as a count — Baker's stage and public persona, as well as her singing voice, were transformed.

In 1934 she took the lead in a revival of Jacques Offenbach's 1875 opera La créole at the Théâtre Marigny on the Champs-Élysées of Paris, which premiered in December of that year for a six month run. In preparation for her performances she went through months of training with a vocal coach. In the words of Shirley Bassey, who has cited Baker as her primary influence, "… she went from a 'petite danseuse sauvage' with a decent voice to 'la grande diva magnifique' … I swear in all my life I have never seen, and probably never shall see again, such a spectacular singer and performer."[citation needed]

Despite her popularity in France, she never obtained the same reputation in America. Upon a visit to the United States in 1935-1936, her performances received poor opening reviews for her starring role in the Ziegfeld Follies and she was replaced by Gypsy Rose Lee later in the run.[citation needed]

Baker returned to Paris in 1937, married a Frenchman, Jean Lion, who was Jewish, and became a French citizen.[10] They were married in the French city of Crévecoeur le Grand. The wedding was presided over by the mayor at the time, Jammy Schmidt. During the ceremony, when she was asked if she was ready to give up her American citizenship, it has been claimed that she renounced it without difficulty.[citation needed]

Her affection for France was so great that when World War II broke out, she volunteered to spy for her adopted country. Baker's agent's brother approached her about working for the French government as an "honorable correspondent", if she happened to hear any gossip at parties that might be of use to her adopted country, she could report it. Baker immediately agreed, since she was against the Nazi stand on race, not only because she was black but because her husband was Jewish. Her café society fame enabled her to rub shoulders with those in-the-know, from high-ranking Japanese officials to Italian bureaucrats, and report back what she heard. She attended parties at the Italian embassy without any suspicion falling on her and gathered information. She helped in the war effort in other ways, such as by sending Christmas presents to French soldiers. When the Germans invaded France, Baker left Paris and went to the Château des Milandes, her home in the south of France, where she had Belgian refugees living with her and others who were eager to help the Free French effort led from England by Charles de Gaulle. As an entertainer, Baker had an excuse for moving around Europe, visiting neutral nations like Portugal, and returning to France. Baker assisted the French Resistance by smuggling secrets written in invisible ink on her sheet music.[citation needed]

She helped mount a production in Marseille to give herself and her like-minded friends a reason for being there. She helped quite a lot of people who were in danger from the Nazis get visas and passports to leave France. Later in 1941, she and her entourage went to the French colonies in North Africa; the stated reason was Baker's health (since she really was recovering from another case of pneumonia) but the real reason was to continue helping the Resistance. From a base in Morocco, she made tours of Spain and pinned notes with the information she gathered inside her underwear (counting on her celebrity to avoid a strip search) and made friends with the Pasha of Marrakesh, whose support helped her through a miscarriage (the last of several) and emergency hysterectomy she had to go through in 1942. Despite the state of medicine in that time and place, she recovered, and started touring to entertain Allied soldiers in North Africa. She even persuaded Egypt's King Farouk to make a public appearance at one of her concerts, a subtle indication of which side his officially neutral country leaned toward. Later, she would perform at Buchenwald for the liberated inmates who were too frail to be moved.[citation needed]

After the war, for her underground activity, Baker received the Croix de guerre, the Rosette de la Résistance, and was made a Chevalier of the Légion d'honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.[11]

In January 1966, she was invited by Fidel Castro to perform at the Teatro Musical de La Habana in Havana, Cuba. Her spectacular show in April of that year led to record breaking attendance. In 1973, Baker opened at Carnegie Hall to a standing ovation. In 1974, she appeared in a Royal Variety Performance at the London Palladium.

Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston, 1926

Josephine Baker dancing the Charleston, 1926

Civil rights activism

Although based in France, Baker supported the American Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s. She protested in her own way against racism, adopting 12 multi-ethnic orphans, whom she called the "Rainbow Tribe."[12] In addition, she refused to perform for segregated audiences in the United States.[4] Her insistence on mixed audiences helped to integrate shows in Las Vegas, Nevada.[citation needed]

In 1951, Baker made charges of racism against Sherman Billingsley's Stork Club in Manhattan, where she alleged that she'd been refused service.[13][14] Actress Grace Kelly, who was at the club at the time, rushed over to Baker, took her by the arm and stormed out with her entire party, vowing never to return (and she never did). However, during his work on the Stork Club book, author and New York Times reporter Ralph Blumenthal was contacted by Jean-Claude Baker, one of Josephine Baker's sons. Having read a Blumenthal-written story about Leonard Bernstein's FBI file, he indicated that he had read his mother's FBI file and using comparison of the file to the tapes, said he thought the Stork Club incident was overblown.[15] The two women became close friends after the incident.[16] Testament to this was made evident when Baker was near bankruptcy and was offered a villa and financial assistance by Kelly (who by then was princess consort of Rainier III of Monaco).

Baker worked with the NAACP.[4] In 1963, she spoke at the March on Washington at the side of Martin Luther King, Jr.[17] Wearing her Free French uniform emblazoned with her medal of the Légion d'honneur, she was the only woman to speak at the rally.[18] After King's assassination, his widow Coretta Scott King approached Baker in Holland to ask if she would take her husband's place as leader of the American Civil Rights Movement. After many days of thinking it over, Baker declined, saying her children were "too young to lose their mother".[3]

Personal life

Baker had 12 children through adoption. She bore only one child herself, stillborn in 1941, an incident which precipitated an emergency hysterectomy. Baker raised two daughters, French-born Marianne and Moroccan-born Stellina, and ten sons, Korean-born Akio, Japanese-born Jeannot (or Janot), Colombian-born Luis, Finnish-born Jari, French-born Jean-Claude and Noël, Israeli-born Moïse, Algerian-born Brahim, Ivorian-born Koffi, and Venezuelan-born Mara.[19][20] For some time, Baker lived with her children and an enormous staff in a castle, Château de Milandes, in Dordogne, France.

There is evidence to suggest that Baker was bisexual. Her son Jean-Claude Baker and co-author Chris Chase state in Josephine: The Hungry Heart that she was involved in numerous lesbian affairs, both while she was single and married, and mention six of her female lovers by name. Clara Smith, Evelyn Sheppard, Bessie Allison, Ada "Bricktop" Smith, and Mildred Smallwood were all African-American women whom she met while touring on the black performing circuit early in her career. She was also reportedly involved intimately with French writer Colette. Not mentioned, but confirmed since, was her affair with Mexican artist Frida Kahlo.[21] Jean-Claude Baker, who interviewed over 2,000 people while writing his book, wrote that affairs with women were not uncommon for his mother throughout her lifetime.[22] He was quoted in one interview as saying:

"She was what today you would call bisexual, and I will tell you why. Forget that I am her son, I am also a historian. You have to put her back into the context of the time in which she lived. In those days, Chorus Girls were abused by the white or black producers and by the leading men if he liked girls. But they could not sleep together because there were not enough hotels to accommodate black people. So they would all stay together, and the girls would develop lady lover friendships, do you understand my English? But wait wait...If one of the girls by preference was gay, she'd be called a bull dyke by the whole cast. So you see, discrimination is everywhere."

Death

On April 8, 1975, Baker starred in a retrospective revue at the Bobino in Paris, Joséphine à Bobino 1975, celebrating her 50 years in show business. The revue, financed by Prince Rainier, Princess Grace, and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, opened to rave reviews. Demand for seating was such that fold-out chairs had to be added to accommodate spectators. The opening-night audience included Sophia Loren, Mick Jagger, Shirley Bassey, Diana Ross and Liza Minnelli.[23]

Four days later, Baker was found lying peacefully in her bed surrounded by newspapers with glowing reviews of her performance. She was in a coma after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage. She was taken to Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital, where she died, aged 68, on April 12, 1975.[23][24] Her funeral was held at L'Église de la Madeleine. The first American woman to receive full French military honors at her funeral, Baker locked up the streets of Paris one last time. She was interred at the Cimetière de Monaco in Monte Carlo.[23]

Legacy

Place Joséphine Baker in the Montparnasse Quarter of Paris was named in her honor. She has also been inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame and the Hall of Famous Missourians. Her name has also been incorporated at Paris Plage, a man-made beach along the river Seine "Piscine Joséphine Baker".

Two of Baker's sons, Jean-Claude and Jarry (Jari), grew up to go into business together, running the restaurant Chez Josephine on Theatre Row, 42nd Street, New York, which celebrates Baker's life and works.[25]

Portrayals

- In 2006, Jérôme Savary produced a musical, "A La Recherche de Josephine - New Orleans for Ever" (Looking for Josephine). The story revolved around the history of jazz and Baker's career.

- In 1991, Baker's life story, The Josephine Baker Story, was broadcast on HBO. Lynn Whitfield portrayed Baker, and won an Emmy Award for her performance.

- Josephine Baker appears in her role as a member of the French Resistance in Johannes Mario Simmel's 1960 novel, "Es Muss Nicht Immer Kaviar Sein" (On a pas toujours du caviar).

- The 2004 erotic novel Scandalous by British author Angela Campion uses Baker as its heroine and is inspired by Baker's sexual exploits and later adventures in the French Resistance. In the novel, Baker, working with a fictional black Canadian lover named Drummer Thompson, foils a plot by French fascists in 1936 Paris.

- Her influence upon and assistance with the careers of husband and wife dancers Carmen De Lavallade and Geoffrey Holder are discussed and illustrated in rare footage in the 2005 Linda Atkinson/Nick Doob documentary, Carmen and Geoffrey.[26][27]

- Beyoncé Knowles has portrayed Baker on various accounts throughout her career. During the 2006 Fashion Rocks show, Knowles performed "Dejá Vu" in a revised version of the Danse banane costume. In Knowles's video for "Naughty Girl", she is seen dancing in a huge champagne glass á La Baker. In I Am... Yours: An Intimate Performance at Wynn Las Vegas, Beyonce lists Baker as an influence of a section of her live show.

- In the 1997 animated film Anastasia, Baker appears with her cheetah during the musical number "Paris Holds the Key (to Your Heart)". A character clearly based upon Baker (topless, wearing the famous 'banana skirt') appears in the opening sequence of the 2003 animated film Les Triplettes de Belleville.

- A German submariner mimics Baker's Danse banane in the film Das Boot.

- In 2010, Keri Hilson portrayed Baker in her single "Pretty Girl Rock".

- Artist Hassan Musa portrayed Baker in a series of paintings called Who needs Bananas?[28]

- In 2011, Sonia Rolland portrayed Baker in the film Midnight in Paris.

Filmography

- La Sirène des tropiques (1927) Aka Siren of the Tropics

- Zouzou (1934)

- Princesse Tam Tam (1935) Aka Princess Tam-Tam

- Fausse alerte (1940) Aka The French Way

- Moulin Rouge (1941)

- An jedem Finger zehn (1954) Aka Ten on Every Finger

- Carosello del varietà (1955)

- Grüsse aus Zürich (1963, ZDF TV)

References

- ^ a b "Josephine Baker (Freda McDonald) Native of St. Louis, Missouri". http://blackmissouri.com/digest/josephine-baker-freda-mcdonald-native-of-st-louis-missouri.html. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ a b "V & A - About Art Deco - Josephine Baker". Victoria and Albert Museum. http://www.vam.ac.uk/vastatic/microsites/1157_art_deco/about. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ a b Baker, Josephine; Bouillon, Joe (1977). Josephine (First ed.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060102128.

- ^ a b c Bostock, William W. (2002). "Collective Mental State and Individual Agency: Qualitative Factors in Social Science Explanation". Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 3 (3). ISSN 1438-5627. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs020317. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ^ "About Josephine Baker: Biography". Official site of Josephine Baker. The Josephine Baker Estate. 2008. http://www.cmgww.com/stars/baker/about/biography.html. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ a b Baker, Jean-Claude; Chase, Chris (1993). Josephine: The Hungry Heart (First ed.). New York: Random House. ISBN 0679409157.

- ^ Jacob M. Appel St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, May 2, 2009. Baker biography

- ^ The Official Josephine Baker Website

- ^ Jazz Book Review, from Josephine Baker: Image & Icon, edited by Olivia Lahs-Gonzales, 2006

- ^ Josephine Baker by Susan Robinson, Gibbs Magazine

- ^ Ann Shaffer (October 4, 2006). "Review of Josephine Baker: A Centenary Tribute". blackgrooves. http://blackgrooves.org/?p=116. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ "Josephine Baker". The African American Registry. 2008. http://www.aaregistry.org/historic_events/view/josephine-baker-entertainer-french-resistance-volunteer-activist. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ Hinckley, David (November 9, 2004). "Firestorm Incident At The Stork Club, 1951". New York Daily News. http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/news/2004/11/09/2004-11-09_firestorm__incident_at_the_s.html. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ "Stork Club Refused to Serve Her, Josephine Baker Claims". Milwaukee Journal. October 19, 1951. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=4TgoAAAAIBAJ&sjid=FCQEAAAAIBAJ&pg=6956,1502149&dq=stork+club+baker&hl=en. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Kissel, Howard (May 3, 2000). "Stork Club Special Delivery Exhibit at the New York Historical Society recalls a glamour gone with the wind". Daily News. http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/entertainment/2000/05/03/2000-05-03__stork_club_special_delivery.html. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

- ^ Skibinsky, Anna (2005-11-20). "Another Look at Grace, Princess of Monaco". Epoch Times. http://www.theepochtimes.com/news/5-11-30/35153.html. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- ^ Bayard Rustin (February 28, 2006). "Profiles in Courage for Black History Month". National Black Justice Coalition. http://nbjc.org/news/black-history-profile-5.html. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Kasher, Steven (1996). The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, 1954-1968. New York: Abbeville Press. ISBN 0789201232.

- ^ Stephen Papich, Remembering Josephine. pg. 149

- ^ "Josephine Baker Biography". Women in History. 2008. http://www.lkwdpl.org/wihohio/bake-jos.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ Herrera, Hayden (1983). A Biography of Frida Kahlo. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060085896.

- ^ "Josephine Baker's Hungry Heart", Gay & Lesbian Review Magazine

- ^ a b c "African American Celebrity Josephine Baker, Dancer and Singer". AfricanAmericans.com. 2008. http://www.africanamericans.com/JosephineBaker.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ Staff writers (April 13, 1975). "Josephine Baker Is Dead in Paris at 68". The New York Times: p. 60. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10E1EF73C5F16768FDDAA0994DC405B858BF1D3. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ^ "Chez Josephine". Jean-Claude Baker. 2009. http://www.chezjosephine.com/jean-claude.html. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- ^ Variety review of the film Carmen and Geoffrey

- ^ Langston Hughes African American Film Festival 2009: Carmen and Geoffrey

- ^ (French) Africultures.com

Further reading

- The Josephine Baker collection, 1926–2001 at Stanford University Libraries

- Baker, J. C. & Chase, C. (1993). Josephine: The Hungry Heart. New York: Random House.

- Bonini, Emmanuel (2000). La veritable Josephine Baker. Paris: Pigmalean Gerard Watelet.

- Kraut, Anthea, Between Primitivism and Diaspora: The Dance Performances of Josephine Baker, Zora Neale Hurston, and Katherine Dunham, Theatre Journal 55 (2003): 433–50.

- Jules-Rosette, Bennetta (2006). "Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image". Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Schroeder, Alan, Ragtime Tumpie (Little, Brown, 1989), an award-winning children's picture book about Baker's childhood in St. Louis and her dream of becoming a dancer.

- Schroeder, Alan, Josephine Baker (Chelsea House, 1990), a young-adult biography.

- Theile, Merlind. "Adopting the World: Josephine Baker's Rainbow Tribe" Spiegel Online International, October 2, 2009.

External links

- Josephine Baker Official website

- Les Milandes- Josephine Baker's castle in France

- Josephine Baker at Allmusic

- Josephine Baker at the Internet Broadway Database

- Josephine Baker at the Internet Movie Database (self)

- Josephine Baker at the Internet Movie Database (character)

- Josephine Baker at Find a Grave

- A la recherche de Joséphine official site

- A Josephine Baker photo gallery

- Josephine Baker Photographs from the Western Historical Manuscript Collection at the University of Missouri–St. Louis

- "Discography at Sony BMG Masterworks". Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. http://web.archive.org/web/20070927195431/http://sonybmgmasterworks.com/artists/josephinebaker/.

- Photographs of Josephine Baker

- The electric body: Nancy Cunard sees Josephine Baker (2003) -- review essay of dance style and contemporary critics

- Guide to Josephine Baker papers at Houghton Library, Harvard University

Categories:- Actors from Missouri

- African American actors

- African American dancers

- African American singers

- Burlesque performers

- American buskers

- American erotic dancers

- American female singers

- American film actors

- Bisexual actors

- Bisexual dancers

- Burials in Monaco

- Cabaret singers

- Columbia Records artists

- Chevaliers of the Légion d'honneur

- Recipients of the Croix de Guerre (France)

- Recipients of the Médaille de la Résistance

- Deaths from cerebral hemorrhage

- Disease-related deaths in France

- French erotic dancers

- French female singers

- French film actors

- French people of American descent

- French Resistance members

- French Roman Catholics

- LGBT African Americans

- LGBT musicians from the United States

- Musicians from Illinois

- Mercury Records artists

- Naturalized citizens of France

- People from St. Louis, Missouri

- RCA Records artists

- Traditional pop musicians

- Vaudeville performers

- Women in World War II

- 1906 births

- 1975 deaths

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.