- Jackdaw

-

This article is about the species Coloeus monedula, sometimes known as the Eurasian Jackdaw. For the species Coloeus dauuricus of eastern Asia, see Daurian Jackdaw. For other uses, see Jackdaw (disambiguation).

Jackdaw

Coloeus monedula spermologus

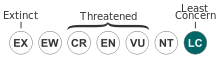

on Ham Common, London, EnglandConservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Passeriformes Family: Corvidae Genus: Coloeus Species: C. monedula Binomial name Coloeus monedula

(Linnaeus, 1758)

Jackdaw range Synonyms Corvus monedula Linnaeus, 1758

The Jackdaw (Coloeus monedula), sometimes known as the Eurasian Jackdaw, European Jackdaw or Western Jackdaw, is a passerine bird in the crow family. Found across Europe, western Asia and North Africa, it is mostly sedentary, although northern and eastern populations migrate south in winter. Four subspecies are recognised. It was originally described as Corvus monedula by Linnaeus, but analysis of its DNA shows it and its closest relative the Daurian Jackdaw to be early offshoots from the genus Corvus, and distinct enough to warrant reclassification in a separate genus Coloeus.

Measuring 34–39 centimetres (13–15 in) in length, the Jackdaw is a black-plumaged bird with a grey nape and distinctive white irises. It is an omnivorous and opportunistic feeder, and eats a wide variety of plant material and invertebrates, as well as food waste from urban areas. The Jackdaw has benefited from clearing of forested areas and is found in farmland and urban areas, as well as open wooded areas and coastal cliffs.

Contents

Taxonomy

The Jackdaw was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th century work, Systema Naturae, as Corvus monedula.[2] The species name monedula is Latin for Jackdaw.[3] The genus Coloeus was created by Peter Pallas in 1766 but most subsequent works included the Jackdaw in the genus Corvus.[4] A 2000 study found that the genetic distance between Jackdaws and other crows to be greater than among the more typical crows.[5] This led Pamela C. Rasmussen to reinstate the older genus name in the Birds of South Asia (2005),[6] a treatment also used in a 1982 systematic list in German by Hans Edmund Wolters.[7] A later relatively study of corvid phylogeny in 2007 that compared DNA sequences in the mitochondrial control region found this and the closely related Daurian Jackdaw (C. dauuricus) of eastern Russia and China to be basal to the core Corvus clade.[8] This genus placement has since been adopted by the International Ornithological Congress in their official list.[9] The two Coloeus species have been reported to hybridize in the Altai Mountains, southern Siberia, and Mongolia. Analysis of the mitochondrial DNA of specimens of the two species from their core distribution ranges show them to be genetically distinct.[8]

Subspecies

There are four recognised subspecies.[10][11] All European subspecies intergrade where their populations meet.[12] C. m. monedula intergrades into C. m. soemmerringii with the transition zone running from Finland south across the Baltic, east Poland to Romania and Croatia.[13]

- C. m. monedula (Linnaeus, 1758), the nominate subspecies, ranges across Scandinavia, from the southern Finland south to Esbjerg and Haderslev in Denmark, and eastern Germany and Poland, and stretching south across eastern central Europe to the Carpathian Mountains and northwestern Romania, Vojvodina in northern Serbia, and Slovenia.[14] It breeds in south-east Norway, southern Sweden and northern and eastern Denmark, with occasional wintering birds in England and France. It has a pale nape and side of the neck, dark throat, and a light grey partial collar of variable extent. It has been recorded as a rare vagrant to Spain.[15]

- C. m. spermologus (Vieillot, 1817) occurs in western and central Europe, from the British Isles, Netherlands and Rhineland in the north, though western Switzerland and into Italy in the southeast, and the Iberian peninsula and Morocco in the south,[14] and winters in the Canary Islands and Corsica. It is darker in colour and lacks the whitish border at the base of the grey collar.[12]

- C. m. soemmerringii (Fischer, 1811) is found in north-eastern Europe, and north and central Asia, from the former Soviet Union to Lake Baikal and north-west Mongolia and south to Turkey, Israel and the eastern Himalayas. Its southwestern limits are Serbia and southern Romania.[14] It winters in Iran and northern India (Kashmir).[6] It is distinguished by its paler nape and side of the neck creating a contrasting black crown, and lighter grey partial collar.

- C. m. cirtensis (Rothschild and Hartert, 1912) is found in Morocco and Algeria in North Africa. The plumage is duller and more uniform dark grey, with the paler nape less distinct.[12] It was formerly found in Tunisia.[14]

Description

Measuring 34–39 centimetres (13–15 in), the Jackdaw is the second smallest species in the genus Corvus. Most of the plumage is a shiny black, with a purple or blue sheen on the crown, forehead and secondaries, and a green-blue sheen on the throat, primaries, and tail. The cheeks, nape and neck are light grey to greyish-silver, and the underparts a slate-grey. The bill and legs are black.[16] The iris of adults is greyish or silvery white. The iris of juvenile Jackdaws is light blue, then brownish, before whitening around a year of age.[16]

In flight, Jackdaws are separable from other corvids by their smaller size, faster and deeper wingbeats and proportionately narrower and less fingered wings. They also have a shorter, thicker neck, a much shorter bill and frequently fly in tighter flocks. The underwing is uniformly grey, unlike choughs.[citation needed]

On the ground, Jackdaws have an upright posture and strut about briskly, their short legs making their gait rapid. They feed with their heads down to horizontal.[17]

Sexes and ages are alike.[10][18] Jackdaws undergo a complete moult from June to September in the western parts of their range, and a month later in the east.[14] Immature birds are duller in plumage.[17]

It is very similar in structure, behaviour and calls to the Daurian Jackdaw, with which its range overlaps in eastern Asia. Adults are readily distinguished, since the Daurian has a pied plumage, but immature birds are much more similar, both species having dark plumage and dark eyes. The Daurian tends to be darker, with a less contrasting nape, than its relative.[19]

Within its range, the Jackdaw is unmistakable, its short bill and grey nape are distinguishing features. From a distance, it might be confused with a Rook, or its silhouette in flight a pigeon or chough.[17]

Voice

Jackdaws are voluble birds. The call, frequently given in flight, is a metallic and somewhat squeaky, "chyak-chyak" or "kak-kak". Perched birds often chatter together, and before settling for the night large roosting flocks make a cackling noise. Jackdaws also have a hoarse, drawn-out alarm-call.[10]

Etymology

The common name jackdaw first appears in the 16th century, and is a compound of the forename Jack used in animal names to signify a small form (e.g. Jack Snipe) and the native English word daw. Formerly jackdaws were simply called daws.[20] Claims that the metallic chyak call is the origin of the jack part of the common name[21] are not supported by the Oxford English Dictionary.[22] Daw, first attested in the 15th century, is conjectured by the Oxford English Dictionary to be derived from an unattested Old English *dawe, citing cognates in Old High German tāha, Middle High German tāhe, tāchele, and modern German Dahle, Dohle, and dialectal Tach, Dähi, Däche, Dacha. The original Old English word cēo (pronounced with initial ch) gave modern English chough; Chaucer sometimes used this word,[20] as did Shakespeare in Hamlet although there has been debate about which species he was referring to.[23] This onomatopoeic name, based on the Jackdaw's call, now refers to corvids of the genus Pyrrhocorax; the Red-billed Chough, formerly particularly common in Cornwall, became known initially as "Cornish Chough" and then just "Chough", the name transferring from one species to the other.[24]

English dialect names are numerous. Scottish and north England dialect has had ka or kae since the 14th century. The midlands form of this was co or coo. Caddow is potentially a compound of ka and dow, a variant of daw. Other dialect or obsolete names include caddesse, cawdaw, caddy, chauk, college-bird (from dialectal college "cathedral"), jackerdaw, jacko, ka-wattie, chimney-sweep bird, from their nesting propensities, and sea-crow, from their frequenting coasts. It was also frequently known quasi-nominally as Jack.[10][25][26][27]

An archaic collective noun for a group of Jackdaws is a "clattering."[28] Another term used is "train,"[29] however, in practice, most people use the more generic term "flock".

Distribution and habitat

Jackdaws are resident over a large area stretching from north-west Africa through virtually all of Europe, including the British Isles and southern Scandinavia, westwards through central Asia to the eastern Himalayas and Lake Baikal. They are resident throughout Turkey, the Caucasus, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and north-west India.[12] The species has a large range, with an estimated global extent of between 1,000,000 and 10,000,000 km². It has a large global population, with an estimated 10 to 29 million individuals in Europe.[30]

Jackdaws are mostly resident, but the northern and eastern populations are more migratory,[13] relocating to wintering areas between September and November and returning between February and early May.[31] Their range expands northwards into Russia to Siberia during summer, and retracts in winter.[10] Jackdaw populations congregate over winter in the Ural Valley in Northwestern Kazakhstan, north Caspian, and Tian Shan region in western China. The species is a winter visitor to the Quetta Valley in western Pakistan[31] They are winter vagrants to Lebanon, first recorded there in 1962.[32] In Syria they are winter vagrants and rare residents with some confirmed breeding.[33] Jackdaws are regionally extinct in Malta and Tunisia.[1] The soemmerringii race occurs in south-central Siberia and extreme northwest China and is accidental to Hokkaido, Japan.[34] They are vagrants to the Faeroe Islands, particularly in the winter and spring, and rarely to Iceland.[17]

A small number of Jackdaws reached the northwest of North America in the 1980s, presumably ship-assisted, and have been found from Atlantic Canada to Pennsylvania.[35] They have also occurred as vagrants in the Faroe Islands, Gibraltar, Iceland, Mauritania and Saint Pierre and Miquelon.[1] The Jackdaw is reported to have once occurred in Egypt.[12]

They inhabit wooded steppes, pasture and cultivated land, coastal cliffs and villages and towns. They thrive as forested areas are cleared and converted to fields and open areas.[12] Habitats with a mix of large trees, buildings and open ground are preferred; the Jackdaw leaves more open fields to the Rook, and more wooded areas to the Common Jay.[17] Along with other corvids such as the Rook, Raven, and Hooded Crow, the Jackdaw spends the European winter in urban parks. Jackdaw populations measured in three urban parks in Warsaw increase from October to December, possibly from birds wintering from areas further to the north.[36] The same data from Warsaw, collected over the years 1977 to 2003, showed that the wintering Jackdaw population had risen 4.25 fold. The cause is unknown, but the reduction in the number of Rooks may have benefited the Jackdaw locally, or Rooks overwintering in Belarus may have driven Jackdaws from there to Warsaw.[37]

Census of bird populations in marginal uplands in Britain show Jackdaws have greatly increased in numbers between the 1970s and 2010, although it is possibly related to recovery from previous periods of persecution.[38]

Behaviour

Jackdaws are highly gregarious and are generally seen in small to large flocks, though males and females pair-bond for life and pairs stay together within flocks. Flock sizes increase in autumn and large flocks group together at dusk for communal roosting,[10] up to several thousand Jackdaws gathering. 40,000 Jackdaws have been recorded at a winter roost in Uppsala in Sweden. Within a roost, mated pairs often settle together.[39] Jackdaws become sexually mature in the first breeding season, and there is little evidence for divorce or extra-pair coupling, even after multiple instances of reproductive failure.[40] Genetic analysis of pairs and offspring shows no evidence of extra-pair coupling.[41] Some pairs do separate in the first few months, but almost all pairings over six months' duration are lifelong, ending only when a partner dies.[42] Widowed or separated birds fare badly, often ousted from nests or territories and unable to rear broods alone.[42]

Jackdaws frequently congregate with Hooded Crows,[18] or Rooks,[17] the latter particularly when migrating or roosting.[42] They have been recorded foraging with the Common Starling, Lapwing or Common Gull for food in northwestern England.[42]

Jackdaws are generally cautious of people in the forest or countryside, but much tamer in urban areas.[39] Like magpies, they are known to steal shiny objects such as jewellery to hoard in nests. John Gay in his Beggar's Opera notes that "A covetous fellow, like a jackdaw, steals what he was never made to enjoy, for the sake of hiding it"[43] and in Tobias Smollett's The Expedition of Humphry Clinker a scathing character assassination by Mr. Bramble runs "He is ungracious as a hog, greedy as a vulture, and thievish as a jackdaw."[44] Al Stewart's song, "Midas Shadow," contains the line, "Conquistador in search of gold for all the jackdaw reasons."

Jackdaw flocks are targets of coordinated hunting by pairs of Lanner Falcons (Falco biarmicus), although larger flocks are more able to elude becoming prey.[45]

Feeding

The Jackdaw forages in open areas and on the ground, but does take some food in trees.[12] Rubbish tips, bins, urban streets and gardens are also visited, more often early in the morning when there are fewer people about.[12] Jackdaws employ various feeding methods, such as jumping, pecking, clod-turning and scattering, probing the soil, and rarely digging. Flies around cow pats are caught by jumping from the ground or at times by dropping vertically from a few metres above onto the cow pat. Earthworms are not usually extracted from the ground by Jackdaws but are eaten from freshly ploughed soil.[46] Compared with other corvids, the Jackdaw spends more time exploring and turning over objects with its bill. A straighter and less downturned bill, and increased binocular vision are advantageous for this foraging strategy, these are more developed in this species than other corvids.[47]

The Jackdaw tends to feed upon small invertebrates found above ground between 2 and 18 mm in length, including larvae and pupae of Curculionidae, Coleoptera, Diptera and Lepidoptera. Snails, spiders and some insects also make up part of their animal diet. The Jackdaw will also eat small rodents, eggs, and chicks, as well as carrion, such as roadkill. Vegetable items consumed include farm grains (barley, wheat and oats), seeds of weeds, elderberries, acorns and various cultivated fruits.[46] A study in southern Spain examining Jackdaw pellets found they contained significant amounts of silicaceous and calcareous grit to aid digestion of vegetable food and supply dietary calcium.[48]

Opportunistic and highly adaptable, the Jackdaw varies its diet markedly depending on available food sources.[49] They have been recorded raiding the nests of the Skylark (Alauda arvensis),[50] Manx Shearwater (Puffinus puffinus), Razorbill (Alca torda), Common Murre (Uria aalge), Grey Heron (Ardea cinerea),[51] Rock Pigeon (Columba livia),[52] and Eurasian Collared Dove (Streptopelia decaocto).[51] A field study of a large city dump on the outskirts of León in northwestern Spain showed Jackdaws forage there in the early morning and dusk, and engage in some degree of kleptoparasitism by stealth of each other.[53]

Jackdaws practice active food sharing, where the initiative for the transfer lies with the donor, with a number of individuals, regardless of sex and kinship. They also share more of a preferred food than a less preferred food.[54]

The Saker Falcon (Falco cherrug) has been reported stealing food from Jackdaws on powerlines in Vojvodina in Serbia.[55]

Breeding

Jackdaws usually breed in colonies with monogamous pairs collaborating to locate a nest site which they then defend from other pairs and predators most of the year.[40] They nest in cavities of trees, cliffs or ruined, and sometimes inhabited, buildings, often in chimneys, or even disused rabbit burrows. The common feature of all is a sheltered site for the nest. The availability of suitable sites influences their presence in a locale.[17] They may use church steeples for nesting, a fact reported in verse by 18th century English poet William Cowper

A great frequenter of the church,

Where, bishoplike, he finds a perch,

And dormitory too.[56]Nests are usually constructed by a mated pair blocking up the crevice by dropping sticks into it; the nest is then built atop the platform formed.[57] This behaviour has led to blocked chimneys and even nests, with the Jackdaw present, crashing down into fireplaces.[58] Nest platforms can attain a great size — John Mason Neale notes that a "Clerk was allowed by the Churchwarden to have for his own use all that the caddows had brought into the Tower: and he took home, at one time, two cart-loads of good firewood, besides a great quantity of rubbish which he threw away."[59]

Gilbert White, in his The Natural History of Selborne, notes that Jackdaws used to nest in crevices beneath the lintels of Stonehenge, and describes an example of the bird using rabbit burrows for nest sites.[29] The Jackdaw has been recorded outcompeting the Tawny Owl (Strix aluco) for nest sites in the Netherlands.[60]

Nests are lined with hair, rags, bark, soil, and many other materials.[21] Paler than those of other corvids,[61] the eggs are smooth, glossy pale blue speckled with dark brown, measuring approximately 36 x 26 mm. Clutches of normally 4–5 eggs, are incubated by the female for 17–18 days until hatching as naked altricial chicks, which are completely dependent on the adults for food. They fledge after 28–35 days,[21] and the parents continue to feed them for another four weeks or so.[42]

Jackdaws hatch asynchronously and incubation begins before clutch completion, which often leads to the death of the last-hatched young. The young which die in the nest do so quickly which minimises parental investment, and hence the brood size comes to fit the available food supply.[62]

Social behaviour

A family group in Bushy Park, London

A family group in Bushy Park, London

Occupying a hole in a wall at Conwy Castle, Clwyd, Wales

Occupying a hole in a wall at Conwy Castle, Clwyd, Wales

The Jackdaw is a highly sociable species outside of the breeding season, occurring in flocks that can contain hundreds of birds.[57]

Konrad Lorenz's book King Solomon's Ring records and analyses the complex social interactions in Jackdaw flocks. Lorenz studied Jackdaws living near his house in Altenberg, Austria, ringing them for identification, and caging them in the winter to prevent their annual migration. He found that Jackdaws have a linear hierarchical group structure with higher-ranked birds dominating lower-ranked birds, and that pair-bonded birds share the same rank.[63]

Jackdaws mate for life, pairing before sexual maturity. Young males establish individual status before pairing with females. Upon pairing the female assumes the same social position as her partner. Unmated females are the lowest members in the pecking order, and are the last to have access to food and shelter.

Lorenz noted a case in which a male that was absent during the dominance struggles and pairings returned to the flock, became the dominant male, and chose one of two unmated females for a mate. This female immediately assumed the dominant position in the social hierarchy and immediately began to peck others. According to Lorenz, the most significant factor of social behaviour was the immediate and intuitive grasp of the new hierarchy by each and every Jackdaw of the flock.[63]

Jackdaws have been observed sharing food and objects. The active giving of food is rare in primates, and in birds is found mainly in the context of parental care and courtship. Jackdaws show much higher levels of active giving than documented for chimpanzees. The function of this behaviour is not fully understood, although it has been found to be detached from nutrition and compatible with hypotheses of mutualism, reciprocity and harassment avoidance. It has been proposed that the sharing may be motivated by prestige enhancement.[64]

The Jackdaw and the White-throated Magpie-Jay are the only two corvids that display non-caching behaviors.[65]

Occasionally the flock makes "mercy killings" during which a sick or injured bird is mobbed until it is killed.[57]

Parasites and diseases

A polyomavirus was isolated from the spleen of a sick Western Jackdaw which subsequently perished. There had been an outbreak of a gastrointestinal illness in Spain which was causing mortalities and appeared to be a co-infection with Salmonella. It has been given the provisional name of crow polyomavirus (CPyV).[66]

The Great Spotted Cuckoo (Clamator glandarius) is a brood parasite of this species.[67]

Cultural depictions and folklore

Ancient Greek authors tell how a Jackdaw, being a social creature, may be caught with a dish of oil which it falls into while looking at its own reflection.[68] The Roman poet Ovid saw them as a harbinger of rain (Amores 2, 6, 34).[69] In Greek legend, a princess Arne was bribed with gold by King Minos of Crete, and was punished for her avarice by being transformed into an equally avaricious Jackdaw, who still seeks shiny things.[70] In Aesop's Fables, the Jackdaw embodies stupidity in one tale, by starving while waiting for figs on a fig tree to ripen, and vanity in another – the daw sought to become king of the birds with borrowed feathers, but was shamed when they fell off.[69] Pliny notes how the Thessalians, Illyrians and Lemnians cherished Jackdaws for destroying grasshoppers' eggs. The Veneti are fabled to have bribed the Jackdaws to spare their crops.[68] Another ancient Greek and Roman adage runs, "The swans will sing when the jackdaws are silent," meaning that educated or wise people will speak after the foolish become quiet.[71]

In some cultures, a Jackdaw on the roof is said to predict a new arrival; alternatively, a Jackdaw settling on the roof of a house or flying down a chimney is an omen of death, and coming across one is considered a bad omen.[69] The 12th century historian William of Malmesbury records the story of a woman who upon hearing a Jackdaw chattering "more loudly than usual," grew pale and became fearful of suffering a "dreadful calamity", and that "while yet speaking, the messenger of her misfortunes arrived."[72]

The Ingoldsby Legends (1837) contains a poem named The Jackdaw of Rheims, which is about a Jackdaw who steals a cardinal's ring and is made a saint.[73] Vincent Bourne, a master of Westminster School, wrote a Latin poem on the jackdaw, which was translated into English by William Cowper, and forms the opening reference to tale by George Augustus Henry Sala about a royal wedding viewed from the point of view of a jackdaw.[74]

A Jackdaw standing on the vanes of a cathedral tower is meant to foretell rain. Czech superstition formerly held that if jackdaws are seen quarrelling, war will follow, and that Jackdaws will not build nests at Sázava having been banished by Saint Procopius.[27]

In his 1979 The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Milan Kundera notes that Franz Kafka's father Hermann had a sign in front of his shop with a Jackdaw painted next to his name, since kavka means jackdaw in Czech.

The Jackdaw features on the Ukrainian town of Halych's coat of arms, the town's name allegedly derived from the East Slavic word for the bird.[citation needed]

In an alternative to 'the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog', 'Jackdaws love my big sphinx of quartz' also includes all of the letters of the alphabet.

References

- ^ a b c "Corvus monedula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.1. International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2009. http://www.iucnredlist.org/apps/redlist/details/146641. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Linnaeus, C (1758) (in Latin). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata.. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 105.

- ^ Simpson, D.P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell. p. 883. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- ^ Mayr E & J C Greenway, Jr., ed (1962). Check-List of birds of the World. Volume 15. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 261. http://www.archive.org/stream/checklistofbirds151962pete#page/260/mode/1up.

- ^ Kryukov, A.P.; Suzuki, H. (2000). "Phylogeography of carrion, hooded and jungle crows (Aves, Corvidae) inferred from partial sequencing of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene.". Russian J. Genet. 36: 922–929.

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton, John C. (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Washington, D.C. and Barcelona: Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. p. 598. ISBN 84-87334-67-9.

- ^ Wolters, Hans E. (1982) (in German). Die Vogelarten der Erde. Hamburg & Berlin: Paul Parey.

- ^ a b Haring, E.; Gamauf, A.; Kryukov, A. (2007). "Phylogeographic patterns in widespread corvid birds". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.016. http://ibss.febras.ru/files/00006265.pdf.

- ^ International Ornithological Congress (30 March 2011). "Vireos, Crows & Allies". World Bird List: Version 2.8.3. WorldBirdNames.org. http://www.worldbirdnames.org/n-vireos.html. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (1999). Collins Bird Guide. Collins. p. 335. ISBN 0002197286.

- ^ "Eurasian Jackdaw Corvus monedula". GlobalTwitcher.com. http://www.globaltwitcher.com/artspec.asp?thingid=26248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Goodwin, p. 75

- ^ a b Offereins, Rudy. "Identification and occurrence of "Eastern" Jackdaws in the Netherlands". http://www.xs4all.nl/~calidris/jackdaw.htm.

- ^ a b c d e Cramp 1994, p. 120.

- ^ Dies, José Ignacio; Lorenzo, Juan Antonio; Gutierrez, Richard et al. (2009). "Report on rare birds in Spain 2007". Ardeola 56 (2): 309–44.

- ^ a b Goodwin, p. 74

- ^ a b c d e f g Cramp 1994, p. 121.

- ^ a b Porter, R.F.; Christensen, S.; Schiermacher-Hansen, F. (1996). Birds of the Middle East. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 405.

- ^ Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1994). Crows and Jays: A Guide to the Crows, Jays and Magpies of the World. A & C Black. pp. 136–37. ISBN 0713639997.

- ^ a b Goodwin, p. 78

- ^ a b c "British Garden Birds: Jackdaw". http://www.garden-birds.co.uk/birds/jackdaw.htm.

- ^ "jackdaw, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed. ed.). 1989. http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50122724.

- ^ Shakespeare, William; Edwards, Philip (2003). Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 241. ISBN 0521532523.

- ^ Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 406–8. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.

- ^ Swan, H. Kirke (1913). A Dictionary of English and Folk-Names of British Birds, With their History, Meaning and first usage: and the Folk-lore, Weather-lore, Legends, etc., relating to the more familiar species. London: Witherby and Co..

- ^ Wright, Joseph (1898–1905). The English Dialect Dictionary. Six volumes. London: Henry Frowde.

- ^ a b Swainson, Charles (1885). Provincial Names and Folk Lore of British Birds. London: Trübner and Co..

- ^ First recorded in John Lydgate's Debate between the Horse, Goose and Sheep, c.1430, as "A clatering of chowhis", and then in Juliana Berners Book of St. Albans, c.1480, as "a Clateryng of choughes."

- ^ a b White, Gilbert (1833). The Natural Nistory of Selborne. London: N. Hailes. p. 163.

- ^ "Birdlife International. Data Zone. Species factsheet: Corvus monedula". http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/species/index.html?action=SpcHTMDetails.asp&sid=5758. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ a b Cramp, p. 124.

- ^ Ramadan-Jaradi, Ghassan; Bara, Thierry; Ramadan-Jaradi, Mona (2008). "Revised checklist of the birds of Lebanon". Sandgrouse 30 (1): 22–69.

- ^ Murdoch, D.A.; Betton, K.F. (2008). "A checklist of the birds of Syria". Sandgrouse (Supplement 2): 12.

- ^ Brazil, Mark (2008). The Birds of East Asia.

- ^ Dunn, John L.; Alderfer, Jonathan (2006). National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America (5th ed.). Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. p. 326.

- ^ Żmihorski, Michał; Halba, Ryszard; Mazgajski, Tomasz D. (2010). "Long-term spatio-temporal dynamics of corvids wintering in urban parks of Warsaw, Poland". Ornis Fennica 87 (2): 61–68. http://www.ornisfennica.org/pdf/vol87-2/3Zmihorski.pdf.

- ^ Mazgajski, Tomasz D.; Żmihorski, Michał; Halba, Ryszard; Wozniak, Agnieszka (2008). "Long-term population trends of corvids wintering in urban parks in central Poland". Polish Journal of Ecology 56 (3): 521–26. http://www.miiz.waw.pl/pliki/pracownicy/zmihorski/Mazgajski_CorvidsWarsawWinteringTrends_PolJEcol2008.pdf.

- ^ Henderson, I. G.; Fuller, R. J.; Conway, G. J.; Gough, S. J. (2004). "Evidence for declines in populations of grassland-associated birds in marginal upland areas of Britain: Capsule We report large declines among summer populations between 1968-80 and 2000". Bird Study 51: 12–19. doi:10.1080/00063650409461327.

- ^ a b Cramp, p. 129.

- ^ a b Emery, Nathan J.; Seed, Amanda M.; von Bayern, Auguste M.P.; Clayton, Nicola S. (29 April 2007). "Cognitive adaptations of social bonding in birds". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London: B Biological Sciences 362 (1480): 489–505.

- ^ Henderson, I. G.; Hart, P. J. B.; Burke, T (2000). "Strict Monogamy in a Semi-Colonial Passerine: The Jackdaw Corvus monedula". Journal of Avian Biology 31 (2): 177–182. doi:10.1034/j.1600-048X.2000.310209.x. JSTOR 3676991.

- ^ a b c d e Cramp, p. 128.

- ^ Gay, John (1760). The Beggar's Opera. Edinburgh: A. Donaldson. p. 36.

- ^ Smollett, Tobias (1857). Humphry Clinker. London: G. Routledge and Co.. p. 78.

- ^ Leonardi, Giovanni (1999). "Cooperative Hunting of Jackdaws by the Lanner Falcon (Falco biarmicus)". Journal of Raptor Research 33 (2): 123–27. http://elibrary.unm.edu/sora/jrr/v033n02/p00123-p00127.pdf.

- ^ a b "The Food and Feeding Behaviour of the Jackdaw, Rook and Carrion Crow". The Journal of Animal Ecology 25 (2): 421–428. November 1956.

- ^ Kulemeyer, Christoph; Asbahr, Kolja; Gunz, Philipp; Frahnert, Sylke; Bairlein, Franz (2009). "Functional morphology and integration of corvid skulls – a 3D geometric morphometric approach". Frontiers in Zoology 6 (2). doi:10.1186/1742-9994-6-2. http://www.frontiersinzoology.com/content/6/1/2.

- ^ Soler, Juan José; Soler, Manuel; Martínez, Juan Gabriel (1993). "Grit Ingestion and Cereal Consumption in Five Corvid Species". Ardea 81 (2): 143–49. http://www.eeza.csic.es/eeza/documentos/soler_4752.pdf.

- ^ Cramp, p. 127.

- ^ Praus, Libor; Weidinger, Karel (2010). "Predators and nest success of Sky Larks Alauda arvensis in large arable fields in the Czech Republic". Bird Study 57 (4): 525–30. doi:10.1080/00063657.2010.506208. http://www.zoologie.upol.cz/clanky_pdf/Weidinger_Bird_Study_2010.pdf.

- ^ a b Cramp, p. 125.

- ^ Hetmański, Tomasz; Barkowska, Miłosława (2007). "Density and age of breeding pairs influence feral pigeon, Columba livia reproduction". Folia Zoologica 56 (1): 71–83. http://www.ivb.cz/folia/56/1/71-83_MS1182.pdf.

- ^ Baglione, Vittorio; Canestrari, Daniela (2009). "Kleptoparasitism and Temporal Segregation of Sympatric Corvids Foraging in a Refuse Dump". The Auk 126 (3): 566–78. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.08146.

- ^ de Kort, Selvino R.; Emery, Nathan J.; Clayton, Nicola S. (2006). "Food sharing in jackdaws, Corvus monedula: what, why and with whom?". Animal Behaviour 72 (2): 297–304. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.10.016.

- ^ Puzović, S. (2008). "Nest occupation and prey grabbing by saker falcon (Falco cherrug) on power lines in the Province of Vojvodina (Serbia)". Archives of Biological Sciences 60 (2): 271–77. doi:10.2298/ABS0802271. http://www.doiserbia.nb.rs/img/doi/0354-4664/2008/0354-46640802271P.pdf.

- ^ The Poetical Works of William Cowper. 2. London: William Pickering. 1853. p. 336.

- ^ a b c Wilmore, S. Bruce (1977). Crows, jays, ravens and their relatives. London: David and Charles.

- ^ Greenoak, F. (1979). All the birds of the air; the names, lore and literature of British birds. London: Book Club Associates.

- ^ Neale, John Mason (1846). "A Few Words to Parish Clerks and Sextons of Country Parishes.". London: Joseph Masters. http://anglicanhistory.org/neale/clerks.html.

- ^ Koning, F. J.; Koning, H. J.; Baeyens, G. (2009). "Long-Term Study on Interactions between Tawny Owls (Strix aluco), Jackdaws (Corvus monedula) and Northern Goshawks (Accipiter gentilis)". Ardea 97 (4): 453-56. doi:10.5253/078.097.0408.

- ^ Goodwin, p. 47

- ^ Gibbons, David Wingfield (June 1987). "Hatching asynchrony reduces parental investment in the Jackdaw". Journal of Animal Ecology 53 (2): 403–414. JSTOR 5056.

- ^ a b Lorenz, Konrad (1964) [1952]. "11. The Perennial Retainers". King Solomon's Ring: New Light on Animal Ways. Translated by Marjorie Kerr Wilson. London: Methuen.

- ^ von Bayern, A.M.P.; de Kort, S.R.; Clayton, N.S.; Emery, N.J.. "Frequent food- and object-sharing during jackdaw (Corvus monedula) socialisation". Ethological Conference, Budapest, Hungary, 2005. http://www.behav.org/IEC/default.php?proc=search&search=a_num&id=406.

- ^ Schoegel, Christian (May 2011). "What You See Is What You Get-Reloaded: Can Jackdaws (Corvus monedula) Find Hidden Food Through Exclusion?". Journal of Comparative Psychology 125 (2): 162–174. doi:10.1037/a0023045. http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/sp-3.4.1b/ovidweb.cgi?&S=EOBEFPDOAIDDPLLCNCBLECFBKHNAAA00&WebLinkReturn=Full+Text%3d&TOC=S.sh.15.16.20.26%7C1. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ^ Johne, R.; Wittig, W.; Fernandez-De-Luco, D.; Hofle, U.; Muller, H. (2006). "Characterization of Two Novel Polyomaviruses of Birds by Using Multiply Primed Rolling-Circle Amplification of Their Genomes". Journal of Virology 80 (7): 3523–3531. doi:10.1128/JVI.80.7.3523-3531.2006. PMC 1440385. PMID 16537620. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1440385.

- ^ Charter, Motti; Bouskila, Amos; Aviel, Shaul; Leshem, Yossi (2005). "First Record of Eurasian Jackdaw (Corvus monedula) Parasitism by the Great Spotted Cuckoo (Clamator glandarius) in Israel". The Wilson Bulletin 117 (2): 201-204. doi:10.1676/04-065.

- ^ a b Thompson, D'Arcy Wentworth (1895). A Glossary of Greek Birds. Oxford. p. 89.

- ^ a b c de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. p. 275. ISBN 0-7204-8021-3.

- ^ Graves, R (1955). "Scylla and Nisus". Greek Myths. London: Penguin. p. 308. ISBN 0-14-001026-2.

- ^ Collected Works of Erasmus: Adages: Ivi1 to Ix100. Translated by Roger A. Mynors. University of Toronto Press. 1989. p. 314.

- ^ Opie, Iona; and Tatem, Moira, ed (19 December 2008). "Jackdaw" (subscription only). A Dictionary of Superstitions. Oxford University Press and Fatih University. http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t72.e807.

- ^ Ingoldsby, Thomas (1865). The Ingoldsby Legends, Or, Mirth and Marvels. London: Richard Bentley. pp. 118–122.

- ^ Sala, George Augustus (1864). After breakfast; or, Pictures done with a quill. London: Tinsley Brother. pp. 9–55.

Cited texts

- Cramp (ed), Stanley, ed (1994). Handbook of the Birds of Europe the Middle East and North Africa, the Birds of the Western Palearctic, Volume VIII: Crows to Finches. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854679-3.

- Goodwin D. (1983). Crows of the World. Queensland University Press, St Lucia, Qld. ISBN 0-7022-1015-3.

Further reading

- Birding World. Harrop, Andrew (2000). "Identification of Jackdaw forms in northwestern Europe." v 13. n 7. pp 290–295.

External links

- Jackdaw videos, photos and sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- Ageing and sexing (PDF), by Javier Blasco-Zumeta

Extant species of family Corvidae Kingdom: Animalia · Phylum: Chordata · Class: Aves · Subclass: Neornithes · Superorder: Neognathae · Order: PasseriformesFamily Corvidae Choughs Treepies PlatysmurusTemnurusOriental

magpiesOld World jays PtilostomusStresemann's

BushcrowZavattariornis

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Corvus

- Birds of Asia

- Birds of Europe

- British Isles coastal fauna

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

Synonyms:

Look at other dictionaries:

Jackdaw — Jack daw , n. [Prob. 2d jack + daw, n.] (Zo[ o]l.) See {Daw}, n. [1913 Webster] … The Collaborative International Dictionary of English

jackdaw — (n.) 1540s, the common name of the daw (Corvus monedula), which frequents church towers, old buildings, etc.; noted for its loquacity and thievish propensities [OED]. See JACK (Cf. jack) (n.) + DAW (Cf. daw). In modern times, parrots are almost… … Etymology dictionary

jackdaw — ► NOUN ▪ a small grey headed crow, noted for its inquisitiveness. ORIGIN from JACK(Cf. ↑jack) + earlier daw (of Germanic origin) … English terms dictionary

jackdaw — [jak′dô΄] n. [ JACK + DAW1] 1. a small European crow (Corvus monedula) with a gray nape 2. any of various birds, as a large tailed grackle (Quiscalus mexicanus) … English World dictionary

jackdaw — /jak daw /, n. 1. a glossy, black, European bird, Corvus monedula, of the crow family, that nests in towers, ruins, etc. 2. See boat tailed grackle. [1535 45; JACK1 + DAW] * * * or daw Crowlike black bird (Corvus monedula) with gray nape and… … Universalium

jackdaw — UK [ˈdʒækˌdɔː] / US [ˈdʒækˌdɔ] noun [countable] Word forms jackdaw : singular jackdaw plural jackdaws a bird with a black head and a grey body that steals shiny objects. It is a type of crow … English dictionary

jackdaw — jack|daw [ˈdʒækdo: US do:] n [Date: 1500 1600; Origin: Jack male name + daw jackdaw (15 19 centuries) (perhaps from an unrecorded Old English dawe)] a black bird like a ↑crow that sometimes steals small, bright objects … Dictionary of contemporary English

jackdaw — [[t]ʤæ̱kdɔː[/t]] jackdaws N COUNT A jackdaw is a large black and grey bird that is similar to a crow, and lives in Europe and Asia … English dictionary

Jackdaw (comics) — Superherobox caption= character name=Jackdaw real name= species= publisher=Marvel UK debut= The Incredible Hulk Weekly #57 (April 1980) creators=Dez Skinn Steve Parkhouse Paul Neary John Stokes alliances= aliases= powers=|Jackdaw is the name of a … Wikipedia

Jackdaw (disambiguation) — A jackdaw is a bird of the crow family.Jackdaw can also refer to: *Jackdaw (band), the Celtic rock band from Buffalo, New York * Jackdaw , song by British band Audience (band), from their third album The House On The Hill *Blackbird (Femizon),… … Wikipedia