- Space policy of the United States

-

The Space policy of the United States includes both the making of space policy through the legislative process, and the execution of that policy by both civilian and military space programs and by regulatory agencies. The early history of United States space policy is linked to the US–Soviet Space Race of the 1960s, which gave way to the Space Shuttle program. There is a current debate on the post-Space Shuttle future of the civilian space program.

Agencies involved in space policy

In the United States, space policy is made by the President of the United States and the United States Congress through the legislative process. In the Executive Office of the President of the United States, the bodies responsible for making space policy include the National Security Council, due to the military and political implications of space policy; the Office of Science and Technology Policy; and the Office of Management and Budget, due to its role in preparing the federal budget. In addition, a separate National Space Council existed at various point in the past.[1]

In the United States Congress, civilian space policy is mainly made by the House Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics and the Senate Subcommittee on Science and Space, while military and intelligence related activities fall under the purview of the House Subcommittee on Strategic Forces and the Senate Subcommittee on Strategic Forces as well as the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. In addition, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee conducts hearings on proposed space treaties, and the various appropriations committees have power over the budgets for space-related agencies. Space policy efforts are supported by Congressional agencies such as the Congressional Research Service and, until it was disbanded in 1995, the Office of Technology Assessment, as well as the budget-related Congressional Budget Office and Government Accountability Office.[2]

The space policy of the United States is carried out by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which is the civilian and scientific space program of the United States, and by various agencies of the Department of Defense, which include efforts regarding communications, reconnaissance, intelligence, mapping, and missile defense, as well as the armed forces' Air Force Space Command, Naval Space Command, and Army Space and Missile Defense Command. In addition, the Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration operates various services with space components, such as the Landsat program.[3]

There are also space advocacy organizations which provide advice to the government and lobby in relation to space goals. These include advocacy groups such as the Space Science Institute, National Space Society, and the Space Generation Advisory Council, the last of which among other things runs the annual Yuri's Night event; learned societies such as the American Astronomical Society and the American Astronautical Society; and policy organizations such as the National Academies.

Space programs in the budget

Further information: NASA BudgetThe research and development budget in the Obama administration's federal budget proposal for fiscal year 2011.[4]

Defense — $78.0B (52.67%)NIH — $32.2B (21.74%)Energy — $11.2B (7.56%)NASA — $11.0B (7.43%)NSF — $5.5B (3.71%)Agriculture — $2.1B (1.42%)Homeland Security—$1.0B (0.68%)Other — $6.6B (4.79%)Funding for space programs occurs through the federal budget process, where it is mainly considered to be part of the nation's science policy. In the Obama administration's budget request for fiscal year 2011, NASA would receive $11.0 billion, out of a total research and development budget of $148.1 billion.[4] Other space activities are funded out of the research and development budget of the Department of Defense, and from the budgets of the other regulatory agencies involved with space issues.

International law

The United States is a party to four of the five space law treaties ratified by the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. The United States has ratified the Outer Space Treaty, Rescue Agreement, Space Liability Convention, and the Registration Convention, but not the Moon Treaty.[5]

The five treaties and agreements of international space law cover "non-appropriation of outer space by any one country, arms control, the freedom of exploration, liability for damage caused by space objects, the safety and rescue of spacecraft and astronauts, the prevention of harmful interference with space activities and the environment, the notification and registration of space activities, scientific investigation and the exploitation of natural resources in outer space and the settlement of disputes."[6]

The United Nations General Assembly adopted five declarations and legal principles which encourage exercising the international laws, as well as unified communication between countries. The five declarations and principles are:

- The Declaration of Legal Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Uses of Outer Space (1963)

- All space exploration will be done with good intentions and is equally open to all States that comply with international law. No one nation may claim ownership of outer space or any celestial body. Activities carried out in space must abide by the international law and the nations undergoing these said activities must accept responsibility for the governmental or non-governmental agency involved. Objects launched into space are subject to their nation of belonging, including people. Objects, parts, and components discovered outside the jurisdiction of a nation will be returned upon identification. If a nation launches an object into space, they are responsible for any damages that occur internationally.

- The Principles Governing the Use by States of Artificial Earth Satellites for International Direct Television Broadcasting (1982)

- The Principles Relating to Remote Sensing of the Earth from Outer Space (1986)

- The Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space (1992)

- The Declaration on International Cooperation in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space for the Benefit and in the Interest of All States, Taking into Particular Account the Needs of Developing Countries (1996)

History

Eisenhower administration

President Dwight Eisenhower was skeptical about human spaceflight, but sought to advance the commercial and military applications of satellite technology. Prior to the Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik 1, Eisenhower had already authorized a ballistic missile program, as well as a scientific satellite program associated with the International Geophysical Year. As a supporter of small government, he sought to avoid a space race which would require an expensive bureaucracy to conduct, and was surprised by and sought to downplay the public response to the Soviet launch of Sputnik.[7]

The National Aeronautics and Space Act creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was passed in 1958. The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which had existed since 1915, was absorbed into NASA upon the suggestion of Eisenhower's science advisor James R. Killian. However, the version of NASA in the bill passed by Congress was substantially stronger than the Eisenhower administration's original proposal. DARPA was also founded around this time, and included space efforts until these were transferred to NASA.[7]

Kennedy administration

President Kennedy's speech at Rice University on September 12, 1962, famous for the quote "We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard." (17 mins 47 secs).

Early in John F. Kennedy's presidency, he was poised to dismantle plans for the Apollo program, which he had opposed as a senator, but postponed any decision out of deference to his vice president whom he had appointed chairman of the National Advisory Space Council[8] and who strongly supported NASA due to its Texas location.[9] This changed with his January 1961 State of the Union address, when he suggested international cooperation in space.

In response to the flight of Yuri Gagarin as the first man in space, Kennedy in 1961 committed the United States to landing a man on the moon by the end of the decade. At the time, the administration believed that the Soviet Union would be able to land a man on the moon by 1967, and Kennedy saw an American moon landing as critical to the nation's global prestige and status. His pick for NASA administrator, James E. Webb, however pursued a broader program incorporating space applications such as weather and communications satellites. During this time the Department of Defense pursued military space applications such as the Dyna-Soar spaceplane program and the Manned Orbiting Laboratory. Kennedy also had elevated the status of the National Advisory Space Council by assigning the Vice President as its chair.[7]

Johnson administration

President Lyndon Johnson was committed to space efforts, and as Senate majority leader and Vice President, he had contributed much to setting up the organizational infrastructure for the space program. However, the costs of the Vietnam War and the programs of the Great Society forced cuts to NASA's budget as early as 1965. However, the Apollo 8 mission carrying the first men into lunar orbit occurred just before the end of his term in 1968.[7]

Nixon administration

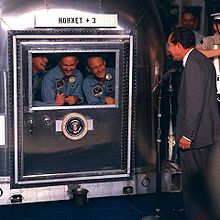

President Nixon visits the Apollo 11 astronauts in quarantine after observing their landing in the ocean from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet.[10]

President Nixon visits the Apollo 11 astronauts in quarantine after observing their landing in the ocean from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Hornet.[10]

Apollo 11, the first moon landing, occurred early in Richard Nixon's presidency, but NASA's budget continued to decline and three of the planned Apollo moon landings were cancelled. The Nixon administration approved the beginning of the Space Shuttle program, but did not support funding of other projects such as a Mars landing, colonization of the Moon, or a permanent space station.[7]

On January 5, 1972, Nixon approved the development of NASA's Space Shuttle program,[11] a decision that profoundly influenced American efforts to explore and develop space for several decades thereafter. Under the Nixon administration, however, NASA's budget declined.[12] NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine was drawing up ambitious plans for the establishment of a permanent base on the Moon by the end of the 1970s and the launch of a manned expedition to Mars as early as 1981. Nixon, however, rejected this proposal.[13] On May 24, 1972, Nixon approved a five-year cooperative program between NASA and the Soviet space program, which would culminate in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, a joint-mission of an American Apollo and a Soviet Soyuz spacecraft, during Gerald Ford's presidency in 1975.[14]

Ford administration

Space policy had little momentum during the presidency of Gerald Ford. NASA funding improved somewhat, the Apollo–Soyuz Test Project occurred and the Shuttle program continued, and the Office of Science and Technology Policy was formed.[7]

Carter administration

The Jimmy Carter administration was also fairly inactive on space issues, stating that it was "neither feasible nor necessary" to commit to an Apollo-style space program, and his space policy included only limited, short-range goals.[7] With regard to military space policy, the Carter space policy stated, without much specification in the unclassified version, that "The United States will pursue Activities in space in support of its right of self-defense."[15]

Reagan administration

President Reagan delivering the March 23, 1983 speech initiating the Strategic Defense Initiative.

President Reagan delivering the March 23, 1983 speech initiating the Strategic Defense Initiative.

The first flight of the Space Shuttle occurred in April 1981, early in President Ronald Reagan's first term. Reagan in 1982 announced a renewed active space effort, which included initiatives such as privatization of the Landsat program, a new commercialization policy for NASA, the construction of Space Station Freedom, and the military Strategic Defense Initiative. Late in his term as president, Reagan sought to increase NASA's budget by 30 percent.[7] However, many of these initiatives would not be compeleted as planned.

The Space Shuttle Challenger disaster happened in January 1986, leading to the Rogers Commission Report on the causes of the disaster, and the National Commission on Space report and Ride Report on the future of the national space program.

George H. W. Bush administration

President George H. W. Bush continued to support space development, announcing the bold Space Exploration Initiative, and ordering a 20 percent increase in NASA's budget in a tight budget era.[7] The Bush administration also commissioned another report on the future of NASA, the Advisory Committee on the Future of the United States Space Program, also known as the Augustine Report.[16]

Clinton administration

During the Clinton administration, Space Shuttle flights continued, and the construction of the International Space Station began.

The Clinton administration's National Space Policy (Presidential Decision Directive/NSC-49/NSTC-8) was released on September 14, 1996.[17] Clinton's top goals were to "enhance knowledge of the Earth, the solar system and the universe through human and robotic exploration" and to "strengthen and maintain the national security of the United States."[18] The Clinton space policy, like the space policies of Carter and Reagan, also stated that "The United States will conduct those space activities necessary for national security." These activities included “providing support for the United States' inherent right of self-defense and our defense commitments to allies and friends; deterring, warning, and if necessary, defending against enemy attack; assuring that hostile forces cannot prevent our own use of space; and countering, if necessary, space systems and services used for hostile purposes."[19] The Clinton policy also said the United States would develop and operate "space control capabilities to ensure freedom of action in space" only when such steps would be "consistent with treaty obligations."[18]

George W. Bush administration

The launch of the Ares I-X prototype on October 28, 2009 was the only flight performed under the Bush administration's Constellation program.

The launch of the Ares I-X prototype on October 28, 2009 was the only flight performed under the Bush administration's Constellation program. Main article: Space policy of the George W. Bush administration

Main article: Space policy of the George W. Bush administrationThe Space Shuttle Columbia disaster occurred early in George W. Bush's term, leading to the report of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board being released in August 2003. The Vision for Space Exploration, announced on January 14, 2004 by President George W. Bush, was seen as a response to the Columbia disaster and the general state of human spaceflight at NASA, as well as a way to regain public enthusiasm for space exploration. The Vision for Space Exploration sought to implement a sustained and affordable human and robotic program to explore the solar system and beyond; extend human presence across the solar system, starting with a human return to the Moon by the year 2020, in preparation for human exploration of Mars and other destinations; develop the innovative technologies, knowledge, and infrastructures both to explore and to support decisions about the destinations for human exploration; and to promote international and commercial participation in exploration to further U.S. scientific, security, and economic interests[20]

To this end, the President's Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy was formed by President Bush on January 27, 2004.[21][22] Its final report was submitted on June 4, 2004.[23] This led to the NASA Exploration Systems Architecture Study in mid-2005, which developed technical plans for carrying out the programs specified in the Vision for Space Exploration. This led to the beginning of execution of Constellation program, including the Orion crew module, the Altair lunar lander, and the Ares I and Ares V rockets. The Ares I-X mission, a test launch of a prototype Ares I rocket, was successfully completed in October 2009.

A new National Space Policy was released on August 31, 2006 that established overarching national policy that governs the conduct of U.S. space activities. The document, the first full revision of overall space policy in 10 years, emphasized security issues, encouraged private enterprise in space, and characterized the role of U.S. space diplomacy largely in terms of persuading other nations to support U.S. policy. The United States National Security Council said in written comments that an update was needed to "reflect the fact that space has become an even more important component of U.S. Economic security, National security, and homeland security." The Bush policy accepts current international agreements by states: "The United States will oppose the development of new legal regimes or other restrictions that seek to prohibit or limit U.S. access to or use of space."[18]

Obama administration

President Barack Obama announces his administration's space policy at the Kennedy Space Center on April 15, 2010. Main article: Space policy of the Barack Obama administration

Main article: Space policy of the Barack Obama administrationThe Obama administration commissioned the Review of United States Human Space Flight Plans Committee in 2009 to review the human spaceflight plans of the United States and to ensure the nation is on "a vigorous and sustainable path to achieving its boldest aspirations in space," covering human spaceflight options after the time NASA plans to retire the Space Shuttle.[24][25][26]

On April 15, 2010, President Obama spoke at the Kennedy Space Center announcing the administration's plans for NASA. None of the 3 plans outlined in the Committee's final report[27] were completely selected. The President cancelled the Constellation program and rejected immediate plans to return to the Moon on the premise that the current plan had become nonviable. He instead promised $6 billion in additional funding and called for development of a new heavy lift rocket program to be ready for construction by 2015 with manned missions to Mars orbit by the mid-2030s.[28] The Obama administration released its new formal space policy on June 28, 2010, and the NASA Authorization Act of 2010, passed on October 11, 2010, enacted many of these space policy goals.

References

- ^ Goldman, Nathan C. (1992). Space Policy:An Introduction. Ames, IA: Iowa State University Press. pp. 79–83.. ISBN 0-8138-1024-8.

- ^ Goldman, pp. 107–112.

- ^ Goldman, pp. 91–97.

- ^ a b Clemins, Patrick J.. "Introduction to the Federal Budget". American Association for the Advancement of Science. http://www.aaas.org/spp/rd/presentations/aaasrd20101118.pdf. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ "OOSA Treaty Database". United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. http://www.oosa.unvienna.org/oosatdb/showTreatySignatures.do;jsessionid=0E0855C654F9C828518C3309CF399FE8.cl013?d-8032343-p=93&d-8032343-o=2&d-8032343-s=2. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- ^ United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (16 Feb 2011). "United Nations Treaties and Principles on Space Law.". http://www.oosa.unvienna.org/oosa/en/SpaceLaw/treaties.html. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Goldman, pp. 84–90.

- ^ Kenney, Charles (2000). John F. Kennedy: The Presidential Portfolio. pp. 115–116.

- ^ Reeves, Richard (1993). President Kennedy: Profile of Power. p. 138.

- ^ Black, Conrad (2007). Richard M. Nixon: A life in Full. New York, NY: PublicAffairs Books. pp. 615–616. ISBN 1586485199.

- ^ "The Statement by President Nixon, January 5, 1972". NASA History Office. January 5, 1972. http://history.nasa.gov/stsnixon.htm. Retrieved November 9, 2008. "President Richard M. Nixon and NASA Administrator James C. Fletcher announced the Space Shuttle program had received final approval in San Clemente, California, on January 5, 1972."

- ^ Butrica, Andrew J. (1998). "Chapter 11 – Voyager: The Grand Tour of Big Science". From Engineering Science to Big Science. The NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA History Office. p. 256. http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4219/Chapter11.html. Retrieved November 9, 2008. "The Bureau of Budget under Nixon consistently reduced NASA's budget allocation."

- ^ Handlin, Daniel (November 28, 2005). "Just another Apollo? Part two". The Space Review. http://www.thespacereview.com/article/507/1. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ^ "The Partnership - ch6-11". Hq.nasa.gov. http://www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4209/ch6-11.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-17.

- ^ Presidential Directive/NSC-37, "National Space Policy," May 11, 1978.

- ^ Warren E. Leary (July 17, 1990). "White House Orders Review of NASA Goals". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/17/science/white-house-orders-review-of-nasa-goals.html. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ^ 2006 U.S. National Space Policy

- ^ a b c Kaufman, Marc (18 October 2006). "Bush Sets Defense As Space Priority". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/10/17/AR2006101701484.html. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- ^ Fact Sheet: National Space Policy

- ^ "The Vision for Space Exploration". NASA. February 2004. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/55583main_vision_space_exploration2.pdf. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ January 30, 2004 Whitehouse Press Release - Establishment of Commission

- ^ Executive Order 13326 - (PDF) From the Federal Register. URL accessed September 4, 2006

- ^ A Journey to Inspire, Innovate, and Discover - (PDF) The Full Report, submitted June 4, 2004. URL accessed September 4, 2006.

- ^ "U.S. Announces Review of Human Space Flight Plans" (PDF). Office of Science and Technology Policy. May 7, 2009. http://www.ostp.gov/galleries/press_release_files/NASA%20Review.pdf. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ "NASA launches another Web site". United Press International. June 8, 2009. http://www.upi.com/Science_News/2009/06/08/NASA-launches-another-Web-site/UPI-78541244470860/. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ Bonilla, Dennis (September 8, 2009). "Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee". NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/offices/hsf/home/index.html. Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- ^ Review of U.S. Human Space Flight Plans Committee; Augustine, Austin, Chyba, Kennel, Bejmuk, Crawley, Lyles, Chiao, Greason, Ride. "Seeking A Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of A Great Nation". Final Report. NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/pdf/396093main_HSF_Cmte_FinalReport.pdf. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- ^ "President Barack Obama on Space Exploration in the 21st Century". Nasa.gov. http://www.nasa.gov/news/media/trans/obama_ksc_trans.html.

Public policy of the United States Agricultural · Arctic · Climate change (G.W. Bush) · Domestic (Reagan, G.W. Bush) · Drug · Economic (G.W. Bush, Obama) · Energy (Obama) ·

Environmental · Fiscal · Foreign (History, Criticism, Reagan, Clinton, G.W. Bush, Obama) · Gun control (Clinton) · Low-level radioactive waste ·

Monetary · Nuclear energy · Science · Social (Obama) · Space (G.W. Bush, Obama) · Stem cell · Telecommunications · TradeCategories:- NASA oversight

- Reports of the United States government

- Space policy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.