- Turks in the Netherlands

-

Turks in the Netherlands Total population 400,000[1][2] - 500,000[3][4][5] 2.35% of the Dutch population

Regions with significant populations Amsterdam (40,000 / 5.2 per cent) · Rotterdam (47,000 / 8 per cent) · The Hague (35,000 / 7.2 per cent · Utrecht (13,500 / 4.5 per cent) · Eindhoven (10,200 / 4.7 per cent) Languages Religion Turks in the Netherlands (occasionally Dutch Turks or Turkish-Dutch) (Dutch: Turkse Nederlander Turkish: Hollanda Türkleri) are citizens of the Netherlands who are of Turkish ancestry. As of 2010, Turks form the largest ethnic minority in the Netherlands.

Contents

History

Number of Turkish-Dutch according to Statistics Netherlands[6] Year Population Year Population 1996 271,514 2004 351,648 1997 279,708 2005 358,846 1998 289,777 2006 364,333 1999 299,662 2007 368,600 2000 308,890 2008 372,714 2001 319,600 2009 378,330 2002 330,709 2010 383,957 2003 341,400 2011 388,967 Until 1961, more people left the Netherlands than moved into the country. It began to face a labour shortage by the mid 1950s, which became more serious during the early 1960s, as the country experienced economic growth rates compareable to the rest of Europe.[7] At the same time, Turkey had a problem of unemployment, low GNP levels and high population rates. So the import of labour solved problems on both ends.[8] The first Turkish immigrants arrived in the Netherlands in the beginning of the 1960s at a time were the Dutch economy was wrestling with a shortage of workers.[9] On 19 August 1964, the Dutch government entered into a 'recruitment agreement' with Turkey.[10] Thereafter, the number of Turkish workers in the Netherlands increased rapidly.[11]

There were two distinct periods of recruitment. During the first period, which lasted until 1966, a large number of Turks came to the Netherlands through unofficial channels. An economic recession began in 1966. Some of the labour migrants were forced to return to Turkey. In 1968, the economy picked up again and a new recruitment period, which was to last until 1974, commenced. The peak of Turkish labour migration occurred during these years. The Turks surpassed other nationalities in numbers and came to represent the Dutch image of guest workers.[12]

Most Turks came to the Netherlands in order to work and save enough money to build a house, expand the family business or start their own business in Turkey. Thus, the decision to emigrate was made primarily for economic reasons. Most of the labour migrants did not come from the lowest strata of the Turkish population, nor did emigration begin in the least developed parts of Turkey, but in the big cities such as Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir. Only later did less urbanised areas become involved with the immigration process. Ultimately, the largest numbers of Turks did come from these areas. Most Turks in the Netherlands come from villages and provincial cities in the middle of the country and on the coast of the Black Sea.[13]

Family reunification

At the end of 1973, the recruitment was nearly brought to a halt, and the Turks were no longer admitted to the Netherlands as labour migrants. Turkish immigration, however, continued practically unabatedly through the process of family reunification.[14] Even more Turkish men began to bring their families to the Netherlands in the 1970s. In the first half of the 1980s, the Turkish net immigration began to decreased- but in 1985, it unexpectedly began to rise again. Most of them had a bride or bridegroom come over from their native land. This marriage immigration still continues, though net immigration has again decreased in the 1990s.[15]

Community building

Turks often worked overtime and led abstemious lives in order to save as much money as possible. This circumstance contributed to the fact that their integration into Dutch society was, to a large extent, limited to the work area. However, Turks became a more visible community in the 1970-80s when more Dutch and Turkish families became neighbours. With the arrival of families, infrastructure grew; in addition to boarding houses and coffee shops, the Turks also opened bakeries, groceries, butchers shops, travel agencies, videos stores, driving schools, prayer rooms and mosques.[16]

Demographics

See also: Demographics of the Netherlands Turkish flag and Dutch flag hanging side by side in the multi-ethnic neighborhood Kruidenbuurt, Eindhoven.

Turkish flag and Dutch flag hanging side by side in the multi-ethnic neighborhood Kruidenbuurt, Eindhoven.

Turkish immigrants first began to settle in big cities in the Netherlands such as Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht as well as the regions of Twente and Limburg, where there was a growing demand for industrial labour. However, not only the capital cities but also medium-sized cities, and even small villages attracted the Turks.[17]

The Turkish population is mostly concentrated in large cities in the west of the country[18] some 36% of Turks live in the Randstad region.[19] The second most common settlements are in the south, in the Limburg region, in Eindhoven and Tilburg, and in the east, in Twente region, in Enschede, Deventer, and Almelo.[20]

According to Statistics Netherlands, as of 2009, the total population of the Netherlands is 16,485,787.[21] The Turkish population is 378,330, thus 2.29% of the total population. This consisted of some 196,000 first generation Turks[22] and 183,000 second generation Turks whose parents originated from Turkey.[23] The total number of third generation Turks is not recorded in Statistics Netherlands. However, Turkish language is spoken by 700,000 people in the Netherlands.[24]

Turks in the four largest cities (Randstad). Regions 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Amsterdam[25] 37,333 37,943 38,337 38,565 38,913 39,654 Rotterdam[26] 44,861 45,254 45,415 - - - The Hague[27][28] 31,052 32,184 - - - - Utrecht[29] 12,148 12,412 12,651 12,918 13,040 - Other Turkish communities

The official estimates of the Turkish immigrant population in the Netherlands does not include Turkish minorities whose origins go back to the Ottoman Empire. In the Netherlands, there are also Bulgarian Turks and Western Thracian Turks. These populations, which have different nationalities, share the same ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious origins as Turkish nationals.

Bulgarian Turks

See also: Turks in Bulgaria10,000-30,000 people from Bulgaria live in the Netherlands. The majority, of about 80%, are ethnic Turks from Bulgaria; most of them have come from the south-eastern Bulgarian district of Kurdzhali[30] and are the fastest-growing group of immigrants in the Netherlands.[31]

Western Thrace Turks

See also: Turks of Western Thrace and Greeks in the NetherlandsA minority of Western Thrace Turks can be found in the Netherlands, especially in the Randstad region. They are registered as Greeks due to their Greek nationality. After Germany, the Netherlands is the most popular destination for Turkish immigrants from Western Thrace.[32]

Culture

Language

See also: Languages of the NetherlandsThe first generation of Turkish immigrants is predominantly Turkish-speaking and has only limited Dutch competence.[33] Thus, for immigrant children, their early language input is Turkish, but the Dutch language quickly enters their lives via playmates and day-care centres. By age six, these children are often bilinguals with their Turkish and Dutch language systems.[34]

Adolescents have developed a code-switching mode which is reserved for in-group use. With older members of the Turkish community and with strangers, Turkish is used, and if Dutch speakers enter the scene, a switch to Dutch is made.[35] The young bilinguals therefore speak normal Turkish with their elders, and a kind of Dutch-Turkish with each other.[36]

The Turkish Mevlana Mosque in Rotterdam was voted the most attractive building in 2006.

The Turkish Mevlana Mosque in Rotterdam was voted the most attractive building in 2006.

Religion

See also: Religion in the Netherlands and Islam in the NetherlandsWhen family reunification resulted in the establishment of Turkish communities, the preservation of Turkish culture became a more serious matter. Most Turks consider Islam to be the centre of their culture.[37] Thus, the majority of Dutch Turks adheres to Sunni Islam, although there is also a considerable Alevi fragment. According to the latest figures issued by Statistics Netherlands, approximately 5% of the Dutch population (850,000 persons), were followers of Islam in 2006. Furthermore, 87% of Turks were followers of Islam.[38] The Turkish community accounted for almost 40% of the Muslim population; thus are the largest ethnic group in the Netherlands adhering to Islam.[39]

Turks are considered to be the best organised ethnic group with its activities and organisations.[40] The Turkish Islamic Cultural Federation (TICF) which was founded in 1979, had 78 member associations by the early 1980s, and continued to grow ro reach 140 by the end of the 1990s. It works closely with the Turkish-Islamic Union for Religious Affairs (Diyanet), which provides the TICF with the imams which it employs in its member mosques.[41]

In April 2006, the Turkish Mevlana Mosque had been voted the most attractive building in Rotterdam in a public survey organsied by the City Information Centre. It had beaten the Erasmus Bridge due to the mosques 'symbol of warmth and hospitality'.[42]

Politics

See also: Politics of the NetherlandsTurks generally support parties on the left (PvdA, D66, GroenLinks, and SP) over parties on the right (CDA, VVD and SGP).[43] In the past, migrants were not as eager to vote, however they are now aware that they can become a decisive factor in the Dutch political system. There has been some criticisms that certain parties (such as the Social Democrats) are becoming the parties of migrants because of the votes they receive from migrants and the increase in the number of elected Turkish candidates.[44] During the Dutch general election (2002), there were 14 candidates of Turkish origin spread out over six party lists which encouraged 55% of Turks to vote, which was a much higher turnout than any other ethnic minorities.[45]

Literature

A number of Turkish-Dutch writers have come to prominence. Halil Gür was one of the earliest, writing short stories about Turkish immigrants. Sadik Yemni is well known for his Turkish-Dutch detective stories. Sevtap Baycili is a more intellectual novelist, who is not limited to migrant themes.

Notable people

See also: List of Dutch Turks-

Deniz Akkoyun, Miss Netherlands 2008.

-

Nebahat Albayrak, former State Secretary for Justice in the Netherlands.

-

Emine Bozkurt, member of the European Parliament.

-

Coşkun Çörüz, politician.

-

Kemal Dervis, economist and politician.

-

Hurşut Meriç, football player.

-

Gökhan Saki, heavyweight kickboxer and martial artist.

-

Esmeral Tunçluer, basketball player.

-

Murat Yıldırım, football player.

See also

- List of Dutch Turks

- Netherlands–Turkey relations

- FC Türkiyemspor

- Turks in Europe

- Turkeye

References

- ^ Netherlands Info Services. "Dutch Queen Tells Turkey "First Steps Taken" On EU Membership Road". http://www.nisnews.nl/public/010307_2.htm. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Dutch News. "Dutch Turks swindled, AFM to investigate". http://www.dutchnews.nl/news/archives/2007/03/dutch_turks_swindled_afm_to_in.php. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- ^ Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi 2008, 11.

- ^ Sarah, Fenwick (2 May 2010). "Airline Plans Direct Flights to North". Cyprus News Report. http://www.cyprusnewsreport.com/?q=node/2983. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ Sabah. "Hollanda Avrupa’nın en streslisi". http://www.isteinsan.com.tr/saglik/hollanda_avrupa_n_n_en_streslisi.html. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- ^ CBS StatLine. "Population; generation, sex, age and origin, 1 January". http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=37325eng&D1=0&D2=a&D3=0&D4=0&D5=225&D6=a&LA=EN&HDR=G2,G3,G4,T&STB=G1,G5&VW=T. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Panayi 1999, 140.

- ^ Ogan 2001, 23-24.

- ^ Vermeulen & Penninx 2000, 154.

- ^ Akgündüz 2008, 61.

- ^ Baumann & Sunier 1995, 37.

- ^ Vermeulen & Penninx 2000, 154.

- ^ Vermeulen & Penninx 2000, 156.

- ^ Kennedy & Roudometof 2002, 60.

- ^ Vermeulen & Penninx 2000, 155.

- ^ Vermeulen & Penninx 2000, 158.

- ^ Yücesoy 2008, 26.

- ^ Vermeulen & Penninx 2000, 158.

- ^ Haug, Compton & Courbage 2002, 277.

- ^ Yücesoy 2008, 26.

- ^ CBS StatLine. "Population; sex, age, marital status, origin and generation, 1 January 2009". http://statline.cbs.nl/StatWeb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=37325eng&D1=0&D2=a&D3=0&D4=a&D5=0&D6=9-13&LA=EN&HDR=G2,G3,G4,T&STB=G1,G5&VW=T. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ^ Statistics Netherlands 2009, 205.

- ^ Statistics Netherlands 2009, 206.

- ^ http://www.staryava.com/web/

- ^ Dienst Onderzoek en Statistiek 2009, 63.

- ^ Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek 2006, 10.

- ^ Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek 2005, 9.

- ^ Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek 2006, 10.

- ^ Gemeente Utrecht 2007, 51.

- ^ Guentcheva, Kabakchieva & Kolarski 2003, 44.

- ^ TheSophiaEcho. "Turkish Bulgarians fastest-growing group of immigrants in the Netherlands". http://www.sofiaecho.com/2009/07/21/758628_turkish-bulgarians-fastest-growing-group-of-immigrants-in-the-netherlands. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Şentürk 2008, 427.

- ^ Strömqvist & Verhoeven 2004, 437.

- ^ Strömqvist & Verhoeven 2004, 438.

- ^ Extra & Verhoeven 1993, 223.

- ^ Extra & Verhoeven 1993, 224.

- ^ Kennedy & Roudometof 2002, 60.

- ^ CBS 2007, 51.

- ^ CBS StatLine. "More than 850 thousand Muslims in the Netherlands (2007)". http://www.cbs.nl/en-GB/menu/themas/bevolking/publicaties/artikelen/archief/2007/2007-2278-wm.htm. Retrieved 2009-04-04.

- ^ Nielsen 2004, 64.

- ^ Nielsen 2004, 65.

- ^ Ulzen 2007, 214-215.

- ^ Messina 2007, 205-206.

- ^ Farrell, Vladychenko & Oliveri 2006, 195.

- ^ Ireland 2004, 146.

Bibliography

- Akgündüz, Ahmet (2008), Labour Migration from Turkey to Western Europe, 1960-1974: A Multidisciplinary Analysis, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0754673901.

- Baumann, Gerd; Sunier, Thijl (1995), Post-Migration Ethnicity: De-essentializing Cohesion, Commitments, and Comparison, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 9055890200.

- CBS (2007), Naar een nieuwe schatting van het aantal islamieten in Nederland, http://www.cbs.nl/: Statistics Netherlands, http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/ACE89EBE-0785-4664-9973-A6A00A457A55/0/2007k3b15p48art.pdf

- Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek (2005), Key figures Rotterdam 2005, http://www.cos.rotterdam.nl/: Centre for Research and Statistics, http://www.cos.rotterdam.nl/Rotterdam/Openbaar/Diensten/COS/Publicaties/PDF/KC2005UK.pdf

- Centrum voor Onderzoek en Statistiek (2006), Key figures Rotterdam 2006, http://www.cos.rotterdam.nl/: Centre for Research and Statistics, http://www.cos.rotterdam.nl/Rotterdam/Openbaar/Diensten/COS/Publicaties/PDF/KC2006UK.pdf

- Dienst Onderzoek en Statistiek (2009), Amsterdam in cijfers 2009, http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/: Stadsdrukkerij Amsterdam, http://www.os.amsterdam.nl/pdf/2009_jaarboek_hoofdstuk_02.pdf

- Extra, Guus; Verhoeven, Ludo Th (1993), Immigrant Languages in Europe, Multilingual Matters, ISBN 1853591793.

- Farrell, Gilda; Vladychenko, Alexander; Oliveri, Federico (2006), Achieving Social Cohesion in a Multicultural Europe: Concepts, Situation and Developments, Council of Europe, ISBN 9287160333.

- Gemeente Utrecht (2007), Bevolking van Utrecht: per 1 januari 2007, http://www.utrecht.nl/: Gemeente Utrecht, http://www.utrecht.nl/images/Secretarie/Bestuursinformatie/Publicaties2007/Bevolkingspublicatie2007.pdf

- Guentcheva, Rossitza; Kabakchieva, Petya; Kolarski, Plamen (2003), Migrant Trends VOLUME I – Bulgaria: The social impact of seasonal migration, http://www.pedz.uni-mannheim.de/: International Organization for Migration, http://www.pedz.uni-mannheim.de/daten/edz-k/gde/04/IOM_I_BG.pdf

- Haug, Werner; Compton, Paul; Courbage, Youssef (2002), The Demographic Characteristics of Immigrant Populations, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 9055890200.

- Huis, Mila van; Nicolaas, Han; Croes, Michel (1997), Migration of the four largest cities in the Netherlands, http://www.cbs.nl/: Statistics Netherlands, http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/24BAD693-1CB9-4D14-9BC8-FA94A87F6727/0/migration.pdf

- Ireland, Patrick Richard (2004), Becoming Europe: Immigration, Integration, and the Welfare State, University of Pittsburgh Press, ISBN 0822958457.

- Kennedy, Paul T.; Roudometof, Victor (2002), Communities Across Borders: New Immigrants and Transnational Cultures, Routledge, ISBN 0415252938.

- Messina, Anthony M. (2007), The Logics and Politics of post-WWII Migration to Western Europe, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521821347.

- Nicolaas, Han; Sprangers, Arno (2000), Migration Motives of non-Dutch immigrants in the Netherlands, http://www.cbs.nl/: Statistics Netherlands, http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/DE05F027-A996-4BA3-A3DC-D97B7C1D0162/0/migrationmotives.pdf

- Nielsen, Jørgen S. (2004), Muslims in Western Europe, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0748618449.

- Ogan, Christine L. (2001), Communication and Identity in the Diaspora: Turkish Migrants in Amsterdam and their Use of Media, Lexington Books, ISBN 0739102699.

- Panayi, Panikos (1999), Outsiders: A History of European Minorities, Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 1852851791.

- Şentürk, Cem (2008), West Thrace Turkish's Immigration to Europe, http://www.sosyalarastirmalar.com: The Journal Of International Social Research, http://www.sosyalarastirmalar.com/cilt1/sayi2/sayi2pdf/senturk_cem.pdf

- Statistics Netherlands (2008), Sustainability Monitor for the Netherlands 2009, http://www.cbs.nl/: Statistics Netherlands, ISBN 978-90-357-1688-9, http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/A36109C6-85F5-4371-8625-9D504C7DF957/0/2009sustainabilitymonitorofthenetherlandspub.pdf

- Statistics Netherlands (2009), Statistical yearbook 2009, http://www.cbs.nl/: Statistics Netherlands, ISBN 978-90-357-1737-4, http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/421A3A8C-956D-451D-89B6-D2113587F940/0/2009a3pub.pdf

- Strömqvist, Sven; Verhoeven, Ludo Th (2004), Relating Events in Narrative: Volume 2: Typological and Contextual Perspectives, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, ISBN 0805846727.

- Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (2008), İnsan Haklarını İnceleme Komisyonu'num Hollanda Ziyareti (16-21 Haziran 2008), http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/: Grand National Assembly of Turkey, http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/komisyon/insanhaklari/belge/kr_23hollanda.pdf

- Vermeulen, Hans; Penninx, Rinus (2000), Immigrant Integration: The Dutch Case, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 9055891762.

- Yücesoy, Eda Ünlü (2008), Everyday Urban Public Space: Turkish Immigrant Women's Perspective, Het Spinhuis, ISBN 9055892734.

- Ulzen, Patricia van (2007), Imagine a Metropolis: Rotterdam's Creative Class, 1970-2000, 010 Publishers, ISBN 9064506213.

External links

- Turks in the Netherlands (Dutch)

Ethnic and national groups in the Netherlands Africans Americans Antilleans · SurinameseAsians Arab Dutch · Armenians · Afghans · Assyrians/Chaldeans/Syriacs · Chinese · Filipinos · Hindoestanen · Indonesians (Indo Eurasians) · Iraqis · Iranians · Japanese · Koreans · Pakistanis · Turkish · VietnameseEuropeans Bold denotes ethnic groups that (partly) originate from within contemporary and historic parts of the NetherlandsTurkish people by country Traditional areas of

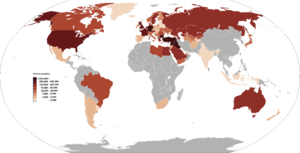

Turkish settlementTurkey · Bosnia and Herzegovina · Bulgaria · Cyprus (Turkish Cypriot diaspora) · Egypt · Georgia · Greece (Crete / Dodecanese / Western Thrace) · Iraq · Kosovo · Macedonia · Montenegro · Romania · Syria · Yemen

Africa Egypt · Libya · South AfricaAmericas Asia Europe Austria · Azerbaijan · Belgium · Bosnia and Herzegovina · Bulgaria · Cyprus (Turkish Cypriot diaspora) · Denmark · Finland · France · Germany (Berlin) · Greece (Crete / Dodecanese / Western Thrace) · Hungary · Ireland · Italy · Kosovo · Liechtenstein · Macedonia · Moldova · Montenegro · Netherlands · Norway · Poland · Romania · Russia · Serbia · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom (London)Oceania Australia · New ZealandSee also Turkish minorities in the former Ottoman Empire · Turks in Europe · Turks in the Balkans · Turks in the former Soviet Union · Turks in the Middle East · Turkish populationCategories:- Turkish diaspora

- Islam in the Netherlands

- Dutch people of Turkish descent

- Ethnic groups in the Netherlands

- Netherlands–Turkey relations

-

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.