- Sine

-

For other uses, see Sine (disambiguation).

Sine

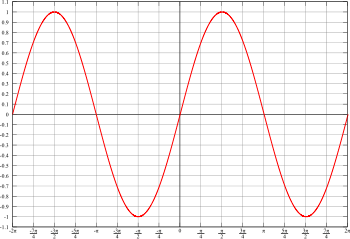

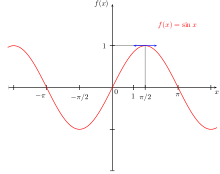

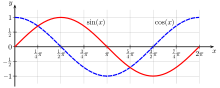

Basic features Parity odd Domain (-∞,∞) Codomain [-1,1] Period 2π Specific values At zero 0 Maxima ((2k+½)π,1) Minima ((2k-½)π,-1) Specific features Root kπ Critical point kπ-π/2 Inflection point kπ Fixed point 0 Variable k is an integer.  The sine function graphed on the Cartesian plane. In this graph, the angle x is given in radians (π = 180°).

The sine function graphed on the Cartesian plane. In this graph, the angle x is given in radians (π = 180°).

In mathematics, the sine function is a function of an angle. In a right triangle, sine gives the ratio of the length of the side opposite to an angle to the length of the hypotenuse.

Sine is usually listed first amongst the trigonometric functions.

Trigonometric functions are commonly defined as ratios of two sides of a right triangle containing the angle, and can equivalently be defined as the lengths of various line segments from a unit circle. More modern definitions express them as infinite series or as solutions of certain differential equations, allowing their extension to arbitrary positive and negative values and even to complex numbers.

The sine function is commonly used to model periodic phenomena such as sound and light waves, the position and velocity of harmonic oscillators, sunlight intensity and day length, and average temperature variations throughout the year.

The function sine can be traced to the jyā and koṭi-jyā functions used in Gupta period Indian astronomy (Aryabhatiya, Surya Siddhanta), via translation from Sanskrit to Arabic and then from Arabic to Latin.[1] The word "sine" comes from a Latin mistranslation of the Arabic jiba, which is a transliteration of the Sanskrit word for half the chord, jya-ardha.[2]

Right-angled triangle definition

For any similar triangle the ratio of the length of the sides remains the same. For example, if the hypotenuse is twice as long, so are the other sides. Therefore respective trigonometric functions, depending only on the size of the angle, express those ratios: between the hypotenuse and the "opposite" side to an angle A in question (see illustration) in the case of sine function; or between the hypotenuse and the "adjacent" side (cosine) or between the "opposite" and the "adjacent" side (tangent), etc.

To define the trigonometric functions for an acute angle A, start with any right triangle that contains the angle A. The three sides of the triangle are named as follows:

- The hypotenuse is the side opposite the right angle, in this case side h. The hypotenuse is always the longest side of a right-angled triangle.

- The opposite side is the side opposite to the angle we are interested in (angle A), in this case side a.

- The adjacent side is the side that is in contact with (adjacent to) both the angle we are interested in (angle A) and the right angle, in this case side b.

In ordinary Euclidean geometry, according to the triangle postulate the inside angles of every triangle total 180° (π radians). Therefore, in a right-angled triangle, the two non-right angles total 90° (π/2 radians), so each of these angles must be greater than 0° and less than 90°. The following definition applies to such angles.

The angle A (having measure α) is the angle between the hypotenuse and the adjacent line.

The sine of an angle is the ratio of the length of the opposite side to the length of the hypotenuse. In our case

Note that this ratio does not depend on the size of the particular right triangle chosen, as long as it contains the angle A, since all such triangles are similar.

Relation to slope

Main article: SlopeThe trigonometric functions can be defined in terms of the rise, run, and slope of a line segment relative to some horizontal line.

- When the length of the line segment is 1, sine takes an angle and tells the rise

- Sine takes an angle and tells the rise per unit length of the line segment.

- Rise is equal to sin θ multiplied by the length of the line segment

In contrast, cosine is used for the telling the run from the angle; and tangent is used for telling the slope from the angle. Arctan is used for telling the angle from the slope.

The line segment is the equivalent of the hypotenuse in the right-triangle, and when it has a length of 1 it is also equivalent to the radius of the unit circle.

Relation to the unit circle

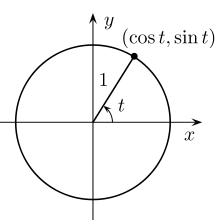

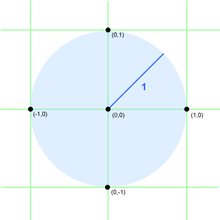

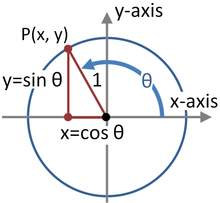

In trigonometry, a unit circle is the circle of radius one centered at the origin (0, 0) in the Cartesian coordinate system.

Let a line through the origin, making an angle of θ with the positive half of the x-axis, intersect the unit circle. The x- and y-coordinates of this point of intersection are equal to cos θ and sin θ, respectively. The point's distance from the origin is always 1.

Unlike the definitions with the right triangle or slope, the angle can be extended to the full set of real arguments by using the unit circle. This can also be achieved by requiring certain symmetries and that sine be a periodic function.

Illustration of a unit circle. The radius has a length of 1. The variable t is an angle measure.

Illustration of a unit circle. The radius has a length of 1. The variable t is an angle measure.

Animation showing the graphing process of y = sin x (where x is the angle in radians) using a unit circle

Animation showing the graphing process of y = sin x (where x is the angle in radians) using a unit circle

Identities

See also: List of trigonometric identitiesExact identities (using radians):

These apply for all values of θ.

Reciprocal

The reciprocal of sine is cosecant. i.e. the reciprocal of sin(A) is csc(A), or cosec(A). Cosecant gives the ratio of the length of the hypotenuse to the length of the opposite side:

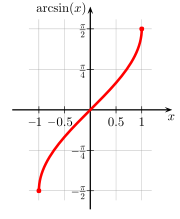

Inverse

The inverse function of sine is arcsine (arcsin or asin) or inverse sine (sin−1). As sine is multivalued, it is not an exact inverse function but a partial inverse function. For example, sin(0) = 0, but also sin(π) = 0, sin(2π) = 0 etc. It follows that the arcsine function is also multivalued: arcsin(0) = 0, but also arcsin(0) = π, arcsin(0) = 2π, etc. When only one value is desired, the function may be restricted to its principal branch. With this restriction, for each x in the domain the expression arcsin(x) will evaluate only to a single value, called its principal value.

k is some integer:

Arcsin satisfies:

and

Calculus

See also: List of integrals of trigonometric functions and Differentiation of trigonometric functionsFor the sine function:

The derivative is:

The antiderivative is:

C denotes the constant of integration.

Other trigonomic functions

It is possible to express any trigonometric function in terms of any other (up to a plus or minus sign, or using the sign function).

Sine in terms of the other common trigonometric functions:

f θ Using plus/minus (±) Using sign function (sgn) f θ = ± per Quadrant f θ = I II III IV cos sin θ

+ + - -

cosθ

+ - - +

cot sin θ

+ + - -

cot θ

+ - - +

tan sin θ

+ - - +

tan θ

+ - - +

sec sin θ

+ - + -

sec θ

+ - - +

Note that for all equations which use plus/minus (±), the result is positive for angles in the first quadrant.

The basic relationship between the sine and the cosine can also be expressed as the Pythagorean trigonometric identity:

where sin2x means (sin(x))2.

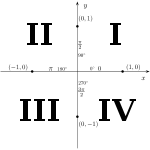

Properties relating to the quadrants

Over the four quadrants of the sine function is as follows.

Quadrant Degrees Radians Value Sign Monotony Convexity 1st Quadrant

0 < x < π / 2 0 < sin x < 1 + increasing concave 2nd Quadrant

π / 2 < x < π 0 < sin x < 1 + decreasing concave 3rd Quadrant

π < x < 3π / 2 − 1 < sin x < 0 − decreasing convex 4th Quadrant

3π / 2 < x < 2π − 1 < sin x < 0 − increasing convex Points between the quadrants. k is an integer.

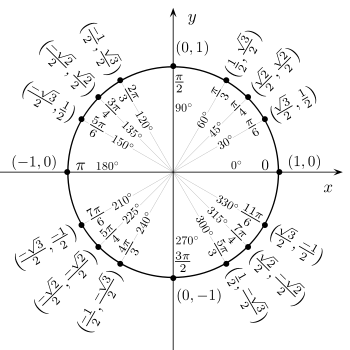

The quadrants of the unit circle and of sin x, using the Cartesian coordinate system.

The quadrants of the unit circle and of sin x, using the Cartesian coordinate system.

Degrees Radians 0 ≤ x < 2π

Radians sin x Point type

0 2πk 0 Root, Inflection

π / 2 2πk + π / 2 1 Maxima

π 2πk − π 0 Root, Inflection

3π / 2 2πk − π / 2 -1 Minima For arguments outside of those in the table, get the value using the fact the sine function has a period of 360° (or 2π rad):

, or use

, or use  .

.For complement of sine, we have

Series definition

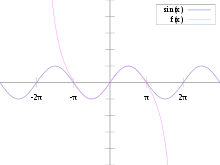

The sine function (blue) is closely approximated by its Taylor polynomial of degree 7 (pink) for a full cycle centered on the origin.

The sine function (blue) is closely approximated by its Taylor polynomial of degree 7 (pink) for a full cycle centered on the origin.

Using only geometry and properties of limits, it can be shown that the derivative of sine is cosine and the derivative of cosine is the negative of sine.

Using the reflection from the calculated geometric derivation of the sine is with the 4n + k-th derivative at the point 0:

This gives the following Taylor series expansion at x = 0. One can then use the theory of Taylor series to show that the following identities hold for all real numbers x (where x is the angle in radians) :[3]

If x were expressed in degrees then the series would contain messy factors involving powers of π/180: if x is the number of degrees, the number of radians is y = πx /180, so

The series formulas for the sine and cosine are uniquely determined, up to the choice of unit for angles, by the requirements that

The radian is the unit that leads to the expansion with leading coefficient 1 for the sine and is determined by the additional requirement that

The coefficients for both the sine and cosine series may therefore be derived by substituting their expansions into the pythagorean and double angle identities, taking the leading coefficient for the sine to be 1, and matching the remaining coefficients.

In general, mathematically important relationships between the sine and cosine functions and the exponential function (see, for example, Euler's formula) are substantially simplified when angles are expressed in radians, rather than in degrees, grads or other units. Therefore, in most branches of mathematics beyond practical geometry, angles are generally assumed to be expressed in radians.

A similar series is Gregory's series for arctan, which is obtained by omitting the factorials in the denominator.

Continued fraction

The sine function can also be represented as a generalized continued fraction:

The continued fraction representation expresses the real number values, both rational and irrational, of the sine function.

Fixed point

Zero is a fixed point of the sine function because sin(0) = 0.

Law of sines

Main article: Law of sinesThe law of sines states that for an arbitrary triangle with sides a, b, and c and angles opposite those sides A, B and C:

This is equivalent to the equality of the first three expressions below:

where R is the triangle's circumradius.

It can be proven by dividing the triangle into two right ones and using the above definition of sine. The law of sines is useful for computing the lengths of the unknown sides in a triangle if two angles and one side are known. This is a common situation occurring in triangulation, a technique to determine unknown distances by measuring two angles and an accessible enclosed distance.

Values

See also: Exact trigonometric constants Some common angles (θ) shown on the unit circle. The angles are given in degrees and radians, together with the corresponding intersection point on the unit circle, (cos θ, sin θ).

Some common angles (θ) shown on the unit circle. The angles are given in degrees and radians, together with the corresponding intersection point on the unit circle, (cos θ, sin θ).

x (angle) sin x Degrees Radians Grads Exact Decimal 0° 0 0g 0 0 180° π 200g 15°

162⁄3g

0.258819045102521 165°

1831⁄3g 30°

331⁄3g

0.5 150°

1662⁄3g 45°

50g

0.707106781186548 135°

150g 60°

662⁄3g

0.866025403784439 120°

1331⁄3g 75°

831⁄3g

0.965925826289068 105°

1162⁄3g 90°

100g 1 1 A memory aid (note it does not include 15° and 75°):

x in degrees 0° 30° 45° 60° 90° x in radians 0 π/6 π/4 π/3 π/2

90 degree increments:

x in degrees 0° 90° 180° 270° 360° x in radians 0 π/2 π 3π/2 2π

0 1 0 -1 0 Other values not listed above:

For angles greater than 2π or less than −2π, simply continue to rotate around the circle; sine periodic function with period 2π:

for any angle θ and any integer k.

The primitive period (the smallest positive period) of sine is a full circle, i.e. 2π radians or 360 degrees.

Relationship to complex numbers

Sine is used to determine the imaginary part of a complex number given in polar coordinates (r,φ):

the imaginary part is:

r and φ represent the magnitude and angle of the complex number respectively. i is the imaginary unit. z is a complex number.

Although dealing with complex numbers, sine's parameter in this usage is still a real number. Sine can also take a complex number as an argument.

Sine with a complex argument

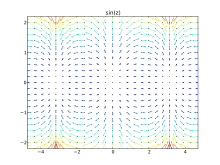

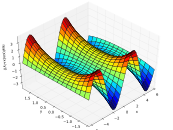

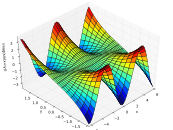

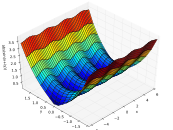

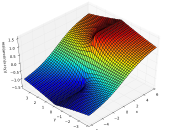

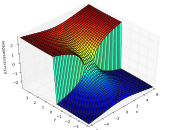

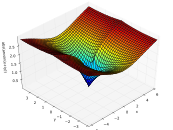

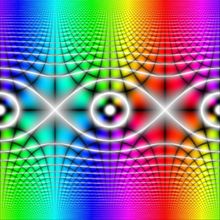

Domain coloring of sin(z) over (-π,π) on x and y axes. Brightness indicates absolute magnitude, saturation represents imaginary and real magnitude.The definition of the sine function for complex arguments z:

where i 2 = −1. This is an entire function. Also, for purely real x,

For purely imaginary numbers:

It is also sometimes useful to express the complex sine function in terms of the real and imaginary parts of its argument:

Usage of complex sine

sin z is found in the functional equation for the Gamma function,

.

.

Which in turn is found in the functional equation for the Riemann zeta-function,

- ζ(s) = 2(2π)s − 1Γ(1 − s)sin(πs / 2)ζ(1 − s)

As a holomorphic function, sin z is a 2D solution of Laplace's equation:

- Δu(x1,x2) = 0

Complex graphs

Sine function in the complex plane real component imaginary component magnitude Sin-1 in the complex plane real component imaginary component magnitude History

Main article: History of trigonometric functionsWhile the early study of trigonometry can be traced to antiquity, the trigonometric functions as they are in use today were developed in the medieval period. The chord function was discovered by Hipparchus of Nicaea (180–125 BC) and Ptolemy of Roman Egypt (90–165 AD).

The function sine (and cosine) can be traced to the jyā and koṭi-jyā functions used in Gupta period Indian astronomy (Aryabhatiya, Surya Siddhanta), via translation from Sanskrit to Arabic and then from Arabic to Latin.[1]

The first published use of the abbreviations 'sin', 'cos', and 'tan' is by the 16th century French mathematician Albert Girard; these were further promulgated by Euler (see below). The Opus palatinum de triangulis of Georg Joachim Rheticus, a student of Copernicus, was probably the first in Europe to define trigonometric functions directly in terms of right triangles instead of circles, with tables for all six trigonometric functions; this work was finished by Rheticus' student Valentin Otho in 1596.

In a paper published in 1682, Leibniz proved that sin x is not an algebraic function of x.[4] Roger Cotes computed the derivative of sine in his Harmonia Mensurarum (1722).[5] Leonhard Euler's Introductio in analysin infinitorum (1748) was mostly responsible for establishing the analytic treatment of trigonometric functions in Europe, also defining them as infinite series and presenting "Euler's formula", as well as the near-modern abbreviations sin., cos., tang., cot., sec., and cosec.[6]

Etymology

Etymologically, the word sine derives from the Sanskrit word for chord, jiva*(jya being its more popular synonym). This was transliterated in Arabic as jiba جــيــب , abbreviated jb جــــب . Since Arabic is written without short vowels, "jb" was interpreted as the word jaib جــيــب , which means "bosom", when the Arabic text was translated in the 12th century into Latin by Gerard of Cremona. The translator used the Latin equivalent for "bosom", sinus (which means "bosom" or "bay" or "fold") [7][8] The English form sine was introduced in the 1590s.

Software implementations

See also: Lookup table#Computing sinesThe sin function, along with other trigonometric functions, is widely available across programming languages and platforms. Some CPU architectures have a built-in instruction for sin, including the Intel x86 FPU. In programming languages, sin is usually either a built in function or found within the language's standard math library. There is no standard algorithm for calculating sin. IEEE 754-2008, the most widely-used standard for floating-point computation, says nothing on the topic of calculating trigonometric functions such as sin.[9] Algorithms for calculating sin may be balanced for such constraints as speed, accuracy, portability, or range of input values accepted. This can lead to very different results for different algorithms in special circumstances, such as for very large inputs, e.g. sin(1022).

A once common programming optimization, used especially in 3D graphics, was to pre-calculate a table of sin values, for example a value per degree. This allowed results to be looked up from a table rather than being calculated in real time. With modern CPU architectures this method typically offers no advantage.

See also

Trigonometry History

Usage

Functions

Generalized

Inverse functions

Further readingReference Identities

Exact constants

Trigonometric tablesLaws and theorems Law of sines

Law of cosines

Law of tangents

Law of cotangents

Pythagorean theoremCalculus Trigonometric substitution

Integrals of functions

Derivatives of functions

Integrals of inverse functions- Sine wave

- Trigonometric functions

- Sinusoidal model

- Discrete sine transform

- Law of sines

- Sine and cosine transforms

- Sine quadrant

- Aryabhata's sine table

- Madhava's sine table

- Madhava series

- Bhaskara I's sine approximation formula

- Hyperbolic function

- List of trigonometric identities

- Proofs of trigonometric identities

- Euler's formula

- Polar sine — a generalization to vertex angles

- Optical sine theorem

- Generalized trigonometry

- Sine–Gordon equation

Notes

- ^ a b Boyer, Carl B. (1991). A History of Mathematics (Second ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 0-471-54397-7, p. 210.

- ^ Victor J Katx, A history of mathematics, p210, sidebar 6.1.

- ^ See Ahlfors, pages 43–44.

- ^ Nicolás Bourbaki (1994). Elements of the History of Mathematics. Springer.

- ^ "Why the sine has a simple derivative", in Historical Notes for Calculus Teachers by V. Frederick Rickey

- ^ See Boyer (1991).

- ^ See Maor (1998), chapter 3, regarding the etymology.

- ^ Victor J Katx, A history of mathematics, p210, sidebar 6.1.

- ^ Grand Challenges of Informatics, Paul Zimmermann. September 20, 2006 – p. 14/31 [1]

Categories:- Trigonometry

- Elementary special functions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

![\begin{align}

\sin x & = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \frac{x^7}{7!} + \cdots \\[8pt]

& = \sum_{n=0}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n}{(2n+1)!}x^{2n+1}, \\[8pt]

\end{align}](2/6727eb26ce3368b1a17e0975fa8c2687.png)