- Differentiation of trigonometric functions

-

Trigonometry History

Usage

Functions

Generalized

Inverse functions

Further readingReference Identities

Exact constants

Trigonometric tablesLaws and theorems Law of sines

Law of cosines

Law of tangents

Law of cotangents

Pythagorean theoremCalculus Trigonometric substitution

Integrals of functions

Derivatives of functions

Integrals of inverse functionsFunction Derivative sin(x) cos(x) cos(x) − sin(x) tan(x) sec 2(x) cot(x) − csc 2(x) sec(x) sec(x)tan(x) csc(x) − csc(x)cot(x) arcsin(x)

arccos(x)

arctan(x)

The differentiation of trigonometric functions is the mathematical process of finding the rate at which a trigonometric function changes with respect to a variable--the derivative of the trigonometric function. Commonplace trigonometric functions include sin(x), cos(x) and tan(x). For example, in differentiating f(x) = sin(x), one is calculating a function f ′(x) which computes the rate of change of sin(x) at a particular point a. The value of the rate of change at a is thus given by f ′(a). Knowledge of differentiation from first principles is required, along with competence in the use of trigonometric identities and limits. All functions involve the arbitrary variable x, with all differentiation performed with respect to x.

It turns out that once one knows the deriatives of sin(x) and cos(x), one can easily compute the derivatives of the other circular trigonometric functions because they can all be expressed in terms of sine or cosine; the quotient rule is then implemented to differentiate this expression. Proofs of the derivatives of sin(x) and cos(x) are given in the proofs section; the results are quoted in order to give proofs of the derivatives of the other circular trigonometric functions. Finding the derivatives of the inverse trigonometric functions involves using implicit differentiation and the derivatives of regular trigonometric functions also given in the proofs section.

Contents

Derivatives of trigonometric functions and their inverses

Proofs of derivative of the sine and cosine functions

Limit of sin(θ)/θ as θ → 0

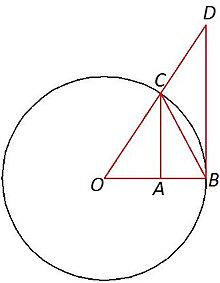

Consider the unit circle shown in the figure. Assume that the angle, say θ, made by the chords OB and OC is small, e.g. less than π/2 radians, i.e. 90°. Let T1 denote the triangle with vertices O, B and C. Let S denote the sector given by the chords OB and OC (i.e. the "slice of pizza" given by cutting along the lines OB and OC). Let T2 denote the triangle with vertices O, B and D. Clearly, the area of T1 is less than the area of S, which is itself less than the area of T2, i.e. area(T1) < area(S) < area(T2).

The area of a triangle is given by one half of the length of the base multiplied by the height. Using u to denote the chosen unit of measurement, we find that the area of T1 is exactly 1⁄2 × ||OB|| × ||CA|| = 1⁄2 × 1 × sin(θ) = 1⁄2·sin(θ) u2. The area of the sector S is exactly 1⁄2·θ u2. Finally, the area of the triangle T2 is exactly 1⁄2 × ||OB|| × ||BD|| = 1⁄2·tan(θ) u2.

Since area(T1) < area(S) < area(T2) we find that, for small θ,

(Recall that tan(θ) = sin(θ)/cos(θ).) If this is true then multiplication by two gives sin(θ) < θ < tan(θ). Take the reciprocals of each term will reverse the inequalities, e.g. 2 < 3 while 1⁄2 > 1⁄3. It follows that

Since θ is small, and so less than π/2 radians, i.e. 90°, it follows that sin(θ) > 0. We can multiply through by the positive quantity sin(θ) without changing the inequalities; whence:

This tells us that for very small θ, sin(θ)/θ is less than 1, but is bigger than cos(θ). However, as θ becomes smaller, cos(θ) becomes bigger and gets closer to 1 (see the cosine graph). The inequality tells us that sin(θ)/θ is always less than 1 and more than cos(θ); but as θ becomes smaller, cos(θ) gets closer to 1. So, sin(θ)/θ is sandwiched, or squeezed, between 1 and cos(θ) as θ becomes smaller and smaller. Obviously, the number 1 is fixed, and so as θ becomes smaller and smaller, cos(θ) forces sin(θ)/θ to move closer and closer to 1. This is made precise by the so-called sandwich theorem, also known as the squeeze theorem.

Limit of [cos(θ) – 1]/θ as θ → 0

The last section enables us to calculate this new limit easily. We find that

The well known identity sin2θ + cos2θ = 1 tells us that cos2θ – 1 = –sin2θ. Using this, the fact that the limit of a product is the product of the limit, and the result from the last section, we find that

Derivative of the sine function

To calculate the derivative of the sine function, sin(θ) we use first principals. By definition:

Using the well know angle formula sin(α+β) = sin(α)cos(β) + sin(β)cos(α) and the two limits from this section and this section, we find that

Derivative of the cosine function

To calculate the derivative of the cosine function, cos(θ) we use first principals. By definition:

Using the well know angle formula cos(α+β) = cos(α)cos(β) – sin(α)sin(β) and the two limits from this section and this section, we find that

Proofs of derivatives of inverse trigonometric functions

The following derivatives are found by setting a variable y equal to the inverse trigonometric function that we wish to take the derivative of. Using implicit differentiation and then solving for dy/dx, the derivative of the inverse function is found in terms of y. To convert dy/dx back into being in terms of x, we can draw a reference triangle on the unit circle, letting θ be y. Using the Pythagorean theorem and the definition of the regular trigonometric functions, we can finally express dy/dx in terms of x.

Differentiating the inverse sine function

We let

Where

Then

Using implicit differentiation and solving for dy/dx:

Substituting

in from above,

in from above,Substituting x = sin y in from above,

Differentiating the inverse cosine function

We let

Where

Then

Using implicit differentiation and solving for dy/dx:

Substituting

in from above, we get

in from above, we getSubstituting

in from above, we get

in from above, we getDifferentiating the inverse tangent function

We let

Where

Then

Using implicit differentiation and solving for dy/dx:

Substituting

into the above,

into the above,Substituting

in from above,

in from above,See also

- Trigonometry

- Calculus

- Derivative

- Table of derivatives

References

Bibliography

- Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Edited by Abramowitz and Stegun, National Bureau of Standards, Applied Mathematics Series, 55 (1964).

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.

![\lim_{\theta \to 0} \left(\frac{\cos\theta - 1}{\theta}\right) = \lim_{\theta \to 0} \left[ \left( \frac{\cos\theta - 1}{\theta} \right) \left( \frac{\cos\theta + 1}{\cos\theta + 1} \right) \right] = \lim_{\theta \to 0} \left( \frac{\cos^2\theta - 1}{\theta(\cos\theta + 1)} \right) .](7/cf7261f85c7c27941ea609477a8c52ee.png)

![\frac{\operatorname{d}}{\operatorname{d}\!\theta}\,\sin\theta = \lim_{\delta \to 0} \left( \frac{\sin\theta\cos\delta + \sin\delta\cos\theta-\sin\theta}{\delta} \right) = \lim_{\delta \to 0} \left[ \left(\frac{\sin\delta}{\delta} \cos\theta\right) + \left(\frac{\cos\delta -1}{\delta}\sin\theta\right) \right] = (1\times\cos\theta) + (0\times\sin\theta) = \cos\theta \, .](3/273ede3686cf57ce6fc598b7ba76a52c.png)

![\frac{\operatorname{d}}{\operatorname{d}\!\theta}\,\cos\theta = \lim_{\delta \to 0} \left( \frac{\cos\theta\cos\delta - \sin\theta\sin\delta-\cos\theta}{\delta} \right) = \lim_{\delta \to 0} \left[ \left(\frac{\cos\delta -1}{\delta}\cos\theta\right) - \left(\frac{\sin\delta}{\delta} \sin\theta\right) \right] = (0 \times \cos\theta) - (1 \times \sin\theta) = -\sin\theta \, .](8/1e832acf875e08eda775eaa2ad92e37e.png)