- Military government of Chile (1973–1990)

-

History of Chile

This article is part of a seriesEarly History Monte Verde Mapuche Inca Empire Colonial times Conquest of Chile Spanish Empire Captaincy General Arauco War Building a nation Patria Vieja War of Independence Patria Nueva 1829 Civil War War of the Confederation Republican period Conservative Republic Liberal Republic War of the Pacific Parliamentary period Chilean Civil War Parliamentary Republic 1924 coup d'état Presidential period 1925 coup d'état Presidential Republic Radical governments Allende and UP era Pinochet regime 1973 coup d'état Military dictatorship Contemporary Chile Transition to democracy Politics of Chile Topical Economic history Chilean coup d'état Political scandals

Chile Portal

Chile was ruled by a military dictatorship headed by Augusto Pinochet from 1973 when Salvador Allende was overthrown in a coup d'etat until 1990 when the Chilean transition to democracy began. The authoritarian military government was characterized by systematic suppression of political parties and the persecution of dissidents to an extent that was unprecedented in the history of Chile. The military government of Chile is considered an example of a police state by scholars.[1][2]

After a highly controversial referendum in 1980 Pinochet who had been proclaimed president in 1974 was elected president and a new constitution approved. In the 1980s the military government, under the influence of the Chicago boys, took a neoliberal stance on economics which has been followed up by the democratic governments that succeeded the dictatorship. The military government of Chile lost power following a referendum in 1988 but the military continued to exercise a great influence on politics through deterrence. Before relinquishing power, an amnesty law was passed, which prevented most members of the military from being prosecuted by the subsequent regime. Another law was also enacted allowing Pinochet to serve as a Senator for life and technically giving him immunity from prosecution without being expelled from the chamber first.

Many of the civilian allies of the military government continued to be influential in Chilean politics. Unión Demócrata Independiente (UDI) is Chile's largest party, and also the one that grouped most of the regime's supporters although the party has since distanced from it.

Contents

Rise to power

Original members of the Government Junta of Chile (1973).

Original members of the Government Junta of Chile (1973). Main article: 1973 Chilean coup d'état

Main article: 1973 Chilean coup d'étatOn August 22, 1973 the Chamber of Deputies of Chile passed, by a vote of 81 to 47, a resolution calling for President Allende to respect the constitution. The measure failed to obtain the two-thirds vote in the Senate constitutionally required to convict the president of abuse of power, but represented a challenge to Allende's legitimacy.

Two weeks before the coup, public dissatisfaction with Allende's government had led to protests like at the Plaza de la Constitución which had been full of Chilean women venting their rage against the rising cost and increasing shortages of food, but which had been dispersed with tear gas.[3] The military seized on such widespread discontent and on the Chamber of Deputies' resolution to then launch the September 11, 1973 coup d'état (see 1973 coup in Chile) and install themselves in power as a Military Government Junta, composed of the heads of the Army, Navy, Air Force and Carabineros (police).

Once the Junta was in power, General Augusto Pinochet soon consolidated his control over the government. Since he was the commander-in-chief of the oldest branch of the military forces (the Army), he was made the titular head of the junta, and soon after President of Chile.

Supression of political activity

Following their takeover of power, the Government Junta formally banned the socialist, Marxist and other leftist parties that had constituted former President Allende's Popular Unity coalition. On September 13, the junta dissolved the Congress and outlawed or suspended all political activities in addition to suspending the constitution. All political activity was declared "in recess".

Pinochet expressed contempt for the Christian Democratic Party's call for a quick return to civilian democracy.[citation needed] However, he did not ban the party. Eduardo Frei, Allende's Christian Democratic predecessor as president, initially supported the coup along with other Christian Democratic leaders. Later, they assumed the role of a loyal opposition to the military rulers, but soon lost most of their influence.

Meanwhile, left-wing Christian Democratic leaders like Radomiro Tomic were jailed or forced into exile.[4][5] The Catholic Church, which at first expressed its gratitude to the armed forces for saving the country from the horrors of a "Marxist dictatorship" became, under the leadership of Cardinal Raúl Silva Henríquez, the most outspoken critic of the regime's social and economic policies. Nonetheless, even Pope John Paul II was criticized[citation needed] for his perceived leniency towards the Pinochet regime.

The military junta began to change during the late 1970s.[citation needed] Due to disagreements with General Pinochet, General Gustavo Leigh was dismissed from the junta in 1978 and replaced by General Fernando Matthei. In 1985 due to the Caso Degollados scandal ("case of the slit throats"), General César Mendoza resigned and was replaced by General Rodolfo Stange.[6]

Human rights violations

Further information: Human rights in Chile“ He shut down parliament, suffocated political life, banned trade unions, and made Chile his sultanate. His government disappeared 3,200 opponents, arrested 30,000 (torturing thousands of them) ... Pinochet’s name will forever be linked to the Desaparecidos, the Caravan of Death, and the institutionalized torture that took place in the Villa Grimaldi complex." ” — Thor Halvorssen, president of the Human Rights Foundation, National Review [7]

The military rule was characterized by systematic suppression of all political dissidence. Scholars later described this as a "politicide" (or "political genocide").[8] Steve J. Stern spoke of a politicide to describe "a systematic project to destroy an entire way of doing and understanding politics and governance."[9]

The worst violence occurred in the first three months of the coup's aftermath, with the number of suspected leftists killed or "disappeared" (desaparecidos) soon reaching into the thousands.[10] In the days immediately following the coup, the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs informed Henry Kissinger, that the National Stadium was being used to hold 5,000 prisoners, and as late as 1975, the CIA was still reporting that up to 3,811 prisoners were still being held in the Stadium.[11] Amnesty International, reported that as many as 7,000 political prisoners in the National Stadium had been counted on 22 September 1973.[12] Press reports have even put the number of detained prisoners in the Stadium at 40,000.[13] Some of the most famous cases of "desaparecidos" are Charles Horman, a U.S. citizen who was killed during the coup itself,[14] Chilean songwriter Víctor Jara, and the October 1973 Caravan of Death (Caravana de la Muerte) where at least 70 persons were killed.[15] Other operations include Operation Colombo during which hundreds of left-wing activists were murdered and Operation Condor, carried out with the security services of other Latin American dictatorships.

Following Pinochet's defeat in the 1988 plebiscite, the 1991 Rettig Commission, a multipartisan effort from the Aylwin administration to discover the truth about the human-rights violations, listed a number of torture and detention centers (such as Colonia Dignidad, the ship Esmeralda or Víctor Jara Stadium), and found that at least 3,200 people were killed or disappeared by the regime.

A later report, the Valech Report (published in November 2004), confirmed the figure of 3,200 deaths but reduced the estimated number of disappearances. It tells of some 28,000 arrests in which the majority of those detained were incarcerated and in a great many cases tortured.[16] Some 30,000 Chileans were exiled and received abroad,[17][18][19] in particular in Argentina, as political refugees; however, they were followed in their exile by the DINA secret police, in the frame of Operation Condor which linked South-American dictatorships together against political opponents.[20] Some 20,000–40,000 Chilean exiles were holders of passports stamped with the letter "L" (which stood for lista nacional), identifyng them as persona non grata and had to seek permission before entering the country.[21] Altogether, at least 200,000 Chileans (about 2% of Chile's 1973 population) were forced to go into exile.[22] Additionally, hundreds of thousands left the country in the wake of the economic crises that followed the military coup during the 1970s and 1980s.[22]

The cases of three persons who were falsely listed as killed or missing during the 1973–1990 military regime have raised some questions about the system of verification of dictatorship victims.[23] In October 1979 the New York Times reported that Amnesty International had documented the disappearance of approximately 1,500 Chileans since 1973.[24] Professor Clive Foss, in The Tyrants: 2500 years of Absolute Power and Corruption (Quercus Publishing 2006), estimates that 1,500 Chileans were killed or disappeared during the Pinochet regime.

The leftist guerrilla groups and their sympathizers were also hit hard during the military regime. The MIR commander, Andrés Pascal Allende, has stated that the Marxist guerrillas lost 1,500–2,000 fighters killed or disappeared.[25] Among the killed and disappeared during the military regime were at least 663 MIR guerrillas.[26] The Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front admitted 49 FPMR guerrillas were killed and hundreds tortured.[27] Many guerrillas confessed under torture and several hundred other young men and women, sympathetic to the guerrillas, were detained and tortured and often killed. Nearly 700 civilians disappeared in the 1974-1977 period, after being detained by the Chilean military and police.[28]

According to the Latin American Institute on Mental Health and Human Rights (ILAS), situations of "extreme trauma" affected about 200,000 persons; this figure includes individuals executed, tortured (following the United Nations definition of torture), forcibly exiled, or having their immediate relatives put under detention.[29] While more radical groups such as the Movement of the Revolutionary Left (MIR) were staunch advocates of a Marxist revolution, the junta deliberately targeted nonviolent political opponents as well.

A court in Chile sentenced, on March 19, 2008, 24 former police officers in cases of kidnapping, torture and murder that happened just after a U.S.-backed coup overthrew President Salvador Allende, a Socialist, on September 11, 1973.[30]

Constitution of 1980

Main article: Chilean constitutional referendum, 1980Chile's new constitution was approved in a national plebiscite held on September 11, 1980. The constitution was approved by 66% of voters under a process which has been described as "highly irregular and undemocratic."[31] The constitution came into force on March 11, 1981.

Economy and free market reforms

Estadio Nacional de Chile as a concentration camp after the coup.

Estadio Nacional de Chile as a concentration camp after the coup. Main articles: Economic history of Chile#1975-81 and Miracle of Chile

Main articles: Economic history of Chile#1975-81 and Miracle of ChileAfter the military took over the government in 1973, a period of dramatic economic changes began. The Chilean economy was still faltering in the months following the coup. As the military junta itself was not particularly skilled in remedying the persistent economic difficulties, it appointed a group of Chilean economists who had been educated in the United States at the University of Chicago. Given financial and ideological support from Pinochet, the U.S., and international financial institutions, the Chicago Boys advocated laissez-faire, free-market, neoliberal, and fiscally conservative policies, in stark contrast to the extensive nationalization and centrally-planned economic programs supported by Allende.[32] Chile was drastically transformed from an economy isolated from the rest of the world, with strong government intervention, into a liberalized, world-integrated economy, where market forces were left free to guide most of the economy's decisions. [32]

Many of these reforms have been continued to this day, and according to the 2009 Index of Economic Freedom, which ranks nations according to tax burden, state control and other factors, Chile is currently the 11th most economically free nation in the world and the most free in Latin America. The resulting effect of these policies on the economy is clear from the figure (below right) showing the growth of GDP per capita since the 1973 overthrow of Salvador Allende and his socialist government. Currently, Chile is the most economically prosperous nation in Latin America according to GDP per capita. Some economists, however, argue that the short-term effects of the change to a free market system in the mid 1970s proved incredibly harmful to the Chilean economy. Instead of a sharp drop in inflation that was expected by the Chicago school economists, inflation reached 375% by conservative estimates.[33] From an economic point of view, the era can be divided into two periods. The first, from 1973 to 1982, corresponds to the period when most of the reforms were implemented. The period ended with the international debt crisis and the collapse of the Chilean economy. At that point, unemployment was extremely high, above 20 percent, and a large proportion of the banking sector had become bankrupt. But this was a worldwide crisis, and as shown in the graph showing growth in GDP per capita did not have a long lasting effect on the Chilean economy. During that first period, an economic policy that emphasized export expansion and growth was implemented. However, some economists argue that the economic recovery of the second period, from 1982 to 1990, was due to an about-face turn around of Pinochet's free market policy and the fact that, in 1982, he nationalized many of the same industries that were nationalized under Allende and fired the Chicago Boys from their government posts.[34]

Pinochet's policies were lauded internationally for transforming the Chilean economy and bringing about an "economic miracle". British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher credited him with bringing about a thriving, free-enterprise economy, while at the same time downplaying the Junta's human rights record, condemning an "organised international Left who are bent on revenge." Pinochet certainly did achieve macroeconomic success with his reforms, hindered somewhat by recession in the early 1980s. GDP growth remained steady, and Chile began a process of integration into the international economy. However, as discussed below, many social costs were paid by the lower strata of Chilean society during his experimentation with economic shock.

Social consequences

The economic policies espoused by the Chicago Boys and implemented by the junta initially caused several economic indicators to decline for Chile's lower classes.[35] Between 1970 and 1989 , there were large cuts to incomes and social services. Wages decreased by 8%.[36] Family allowances in 1989 were 28% of what they had been in 1970 and the budgets for education, health and housing had dropped by over 20% on average.[36][37] The massive increases in military spending and cuts in funding to public services coincided with falling wages and steady rises in unemployment, which averaged 26% during the worldwide economic slump of 1982–1985[36] and eventually peaked at 30%.

In 1990, the LOCE act on education initiated the dismantlement of public education.[38] According to economist Manuel Riesco:

"Overall, the impact of neoliberal policies has reduced the total proportion of students in both public and private institutions in relation to the entire population, from 30 per cent in 1974 down to 25 per cent in 1990, and up only to 27 per cent today. If falling birth rates have made it possible today to attain full coverage at primary and secondary levels, the country has fallen seriously behind at tertiary level, where coverage, although now growing, is still only 32 per cent of the age group. The figure was twice as much in neighbouring Argentina and Uruguay, and even higher in developed countries—South Korea attaining a record 98 per cent coverage. Significantly, tertiary education for the upper-income fifth of the Chilean population, many of whom study in the new private universities, also reaches above 70 per cent."[38]

The junta relied on the middle class, the oligarchy, huge foreign corporations, and foreign loans to maintain itself.[39] Under Pinochet, funding of military and internal defence spending rose 120% from 1974 to 1979. Citation for both of these claims covered under Remmer, 1989--> Due to the reduction in public spending, tens of thousands of employees were fired from other state-sector jobs.[40] The oligarchy recovered most of its lost industrial and agricultural holdings, for the junta sold to private buyers most of the industries expropriated by Allende's Popular Unity government.

Financial conglomerates became major beneficiaries of the liberalized economy and the flood of foreign bank loans. Large foreign banks reinstated the credit cycle, as the Junta saw that the basic state obligations, such as resuming payment of principal and interest installments, were honored. International lending organizations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Inter-American Development Bank lent vast sums anew.[36] Many foreign multinational corporations such as International Telephone and Telegraph (ITT), Dow Chemical, and Firestone, all expropriated by Allende, returned to Chile.[36]

Guerrilla resistance

After the coup, left-wing organizations tried to set up groups of resistance fighters against the regime. Some of them, known as the GAP (Grupo de Amigos Personales), had previously served as bodyguards of President Allende. Many activists created groups of resistance groups from refugees abroad. The Lautaro Youth Movement (MJL) was formed in December 1982 and the Communist Party of Chile set up an armed wing, which became in 1983 the FPMR (Frente Patriótico Manuel Rodríguez). The main guerrilla group, known as the MIR (Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria), suffered heavy casualties in the coup's immediate aftermath, and most of its members fled the country.[41] Andreas Pascal Allende, a nephew of President Allende led the MIR from 1974–1976, then made his way to Cuba. Nevertheless, in the first three months of military rule, the Chilean forces recorded 162 military deaths.[42] A total of 756 servicemen and police are reported to have been killed or wounded in clashes with guerrillas in the 1970s.[43] Among the killed and disappeared during the military regime were at least 663 Marxist MIR guerrillas.[26] The MIR commander, Andrés Pascal Allende, has admitted that the Marxist guerrillas lost 1,500-2,000 fighters killed or disappeared.[44] Many guerrillas confessed under torture and several hundred other young men and women, sympathetic to the guerrillas, were detained and tortured and often killed. Nearly 700 civilians disappeared in the 1974-1977 period, after being detained by the Chilean military and police.[28]

Actions

1970s

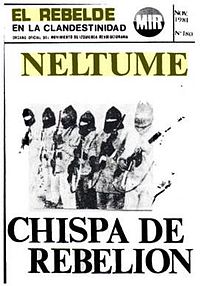

MIR newspaper El Rebelde saying; Neltume, Spark of Rebellion.

MIR newspaper El Rebelde saying; Neltume, Spark of Rebellion.

On February 19, 1975, four captured MIR commanders went on national television to urge their guerrillas to lay down their arms. According to them, the MIR leadership was in ruins: of the 52 commanders of the MIR, nine had been killed, 24 were prisoners, ten were in exile, one had been expulsed from the group, and eight were still at large.[45] On 18 November 1975, MIR guerrillas killed a 19-year-old army conscript (Private Hernán Patricio Salinas Calderón).[46] On 24 February 1976, MIR guerrillas in a gunbattle with Chilean secret police, shot and killed a 41-year-old carabinero sergeant (Tulio Pereira Pereira).[47] The Chilean secret police on this occasion were met with a hail of automatic weapons fire, killing a carabinero and a girl.[48] On 28 April 1976, MIR guerrillas shot and killed a 29-year-old carabineros corporal (Bernardo Arturo Alcayaga Cerda) while he was walking home in the Santiago suburb of Pudahuel.[47] On 16 October 1977, MIR guerrillas exploded 10 bombs in Santiago. In 1978 the MIR sought to reestablish a presence in Chile and launched "Operation Return" which involved clandestine entry, recruitment, bombings and bank robberies in Santiago that briefly shook the military regime.[49] In February, 1979 MIR guerrillas bombed the US-Chile Cultural Institute in Santiago, causing considerable damage. In 1979, about 40 bombings were blamed on MIR guerrillas.

1980s

On July 15, 1980 three guerrillas in blue overalls and yellow hardhats ambushed the car of lieutenant-colonel Roger Vergara Campos, director of the Chilean Army Intelligence School, and killed him and wounded his driver in a barrage of bullets from automatic rifles.[50]

In a message sent to Santiago press agencies in February 1981 the MIR claimed to have carried out more than 100 attacks during 1980, among them the bombing of electricity pylons in Santiago and Valparaiso on November 11 which caused widespread blackouts, and bomb attacks on three banks in Santiago on December 30 in which one carabinero was killed and three people wounded.[51] In November, 1981, MIR guerrillas killed three member of the Investigative Police as they stood in front of the home of the chief minister of the presidential staff. In sweeps carried out from June to November 1981, security forces destroyed two MIR bases in the mountains of Neltume, seizing large caches of munitions and killing a number guerrillas.[52] MIR guerrillas retaliated and carried out twenty-six bomb attacks during March and April 1983.[41]

Leftist guerrillas, waiting in a yellow pick-up truck, ambushed on August 30, 1983 the governor of Santiago, retired major-general Carol Urzua Ibáñez as he left his home, killing him and two of his bodyguards (army corporals Carlos Riveros Bequiarelli and José Domingo Aguayo Franco) in a hail of submachine-gun fire.[53] In October and November 1983, MIR guerrillas bombed four US-associated targets. Guerrillas killed two policemen (carabinieri Francisco Javier Pérez Brito and sergeant Manuel Jesús Valenzuela Loyola) on December 28, 1983.[54]

On March 31, 1984 a police bus in downtown Santiago was destroyed with a bomb, killing a carabinero and injuring at least 11.[55] On 29 April 1984, MIR guerrillas exploded 11 bombs, derailing a subway train in Santiago and injuring 22 passengers, including seven children.[56] On 5 September 1984, guerrillas shot and killed 27-year-old army lieutenant Julio Briones Rayo in Copiapó.[57] On November 2, 1984 a bus carrying carabineros was attacked with a grenade during Chile's national cycling championship; four carabineros were killed.[58] On November 4, 1984 five guerrillas riding in a van hurled bombs and fired automatic weapons at a suburban Santiago police station, killing two carabineros and wounded three more.[59] A month later, another carabinero was killed in a similar attack. On 25 March 1985, MIR guerrillas planted a bomb in Hotel Araucano in Concepcion that killed marine sergeant René Osvaldo Lara Arriagada and army sergeant Alejandro del Carmen Avendaño Sánchez, who were attempting to defuse the bomb. On December 6, 1985 a carabinero was shot to death by four guerrillas who opened fire on him with submachine-guns as he walked home.[60] The total number of documented terrorist actions during 1984 and 1985 was 866.[61]

In February 1986 a car bomb destroyed a bus filled with riot police, mutilating 16 policemen. One carabinero later died of his wounds. The MIR claimed responsibility for the bombing.[62] In May 1986 MIR guerrillas threw sulphuric acid into a bus, seriously injuring six people, including two children.[63] On July 25, 1986 a bomb planted in a trash can exploded at a crowded bus stop a few yards from the presidential palace, wounding at least 24 people.[64] On 6 August 1986, security forces discovered 80 tons of weapons at the tiny fishing harbor of Carrizal Bajo, smuggled into the country by the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front (FPMR). The shipment of Carrizal Bajo included C-4 plastic explosives, 123 RPG-7 and 180 M72 LAW rocket launchers as well as 3,383 M-16 rifles.[65] On September 7, 1986, about 30 FPMR guerrillas attempted to kill Pinochet. Pinochet narrowly escaped the assassination attempt on his motorcade, but five army corporals were killed and eleven soldiers and carabineros were wounded in the ambush.[66] This failed operation led to an internal crisis of the group, many of its leading members being arrested by the security forces. In October, 1986 MIR guerrillas attacked a police station in Limache with gunfire, seriously wounding five policemen. One carabinero later died of his wounds. On November 5, 1986 guerrillas threw an incendiary bomb into a bus in Viña del Mar, seriously injuring three women (Rosa Rivera Fierro, Sonia Ramírez Salinas and Marta Sepúlveda Contreras). Rosa Rivera Fierro, later died of her wounds. On 28 November 1986, MIR guerrillas after having been stopped by a police vehicles, shot and killed 31-year-old Carabinero Lieutenant Jaime Luis Sáenz Neira

On September 11, 1987 a police vehicle was completely destroyed in a bomb attack in Santiago, killing two carabineros. On January 20, 1988 a bomb planted by MIR guerrillas in the Capredena Medical Center in Valparaiso killed a 65-year-old female pensioner (Berta Rosa Pardo Muñoz) and wounded 15 others females.[67] On January 26, MIR guerrillas planted a bomb in a house in La Cisterna that killed 42-year-old Major Julio Eladio Benimeli Ruz, commander of the carabineros special operations group. In June, 1988 MIR guerrillas conducted a series of bombings in Santiago, at various banks. FPMR guerrillas that month killed 43-year-old Lieutenant-Colonel Miguel Eduardo Rojas Lobos of the Chilean Army, after he had parked his car in the Santiago suburb of San Joaquín.[68] On 10 July 1989, 26-year-old Carabineros corporal Patricio Rubén Canihuante Astudillo was shot in the head at point-blank range as he guarded a building in Viña del Mar.

Post-Pinochet activity

The election of a civilian government in Chile did not end guerrilla activities. Within a few months after President Patricio Aylwin's accession to power, leftist militants showed that they remained committed to armed struggle and were responsible for a number of terrorist incidents.[61] On May 10, 1990, two guerrillas wearing school uniforms assassinated carabineros Colonel Luis Fontaine, a former head of the antiterrorist department of the carabineros, Chile's national police force. Two policemen were killed on August 10, 1990 in a working-class Santiago suburb and two more were injured in an attack on a bus.[69] On November 14, 1990, gendarmes transferred Marco Ariel Antonioletti, a senior MJL leader from jail to hospital for treatment. MJL guerrillas fought their way into the Sótero del Río Hospital but were forced to withdraw, after having killed four gendarmes and one carabinero. Chile's Investigations Police later shot Antonioletti in the forehead, killing him. On January 24, 1991 MJL guerrillas ambushed and killed two carabineros. On February 28, 1991 a carabinero policeman died in a shoot-out in Santiago with leftist guerrillas of the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front.[70] On April 1, FPMR guerrillas assassinated right-wing senator Jaime Guzman, killing him as he left a university campus in Santiago. On September 9 three guerrillas kidnapped Cristian Edwards, whose family run El Mercurio newspaper. After his family paid $1 million in ransom, the FPMR freed him. On 22 January 1992, two FPMR guerrillas (Fabián López Luque and Alex Muñoz Hoffman)were killed trying to rob a Prosegur cash delivery armoured van at the Pontifical Catholic University in Santiago. On September 11, 1998 three police stations—La Pincoya, La Granja and La Victoria—were attacked with firearms, incendiary bombs and rocks and 36 were carabineros were wounded in violence related to the 25th anniversary commemorations of the military coup.[71] In 2006, on the 33rd anniversary of the September 11, 1973 military coup, 79 carabineros were wounded in clashes with rioters.[72] In September 2007, a carabinero policeman was killed after being shot in the face and around 40 were wounded during clashes with protesters marking the 34th anniversary of the military coup.[73] The following month, MJL guerrillas killed carabineer Luis Moyano Farías during the robbery of Banco Security in Santiago. In clashes with protesters commemorating the 35th anniversary of the military coup, 29 carabineros were wounded in September 2008.[74] In September 2009, 19 Carabineros were wounded in clashes with protestors marking the 36th anniversary of the coup.[75] The murders, lootings, thefts and other forms of appropriation that took place in the aftermath of the devastating 2010 earthquake in Chile, were in part promoted and legitimated by the MIR movement.[76]

Macroeconomics

Pinochet's policies eventually led to substantial GDP growth, in contrast to the negative growth seen in the early years of his administration. The upper 20% of income earners ultimately benefited the most from such growth, receiving 85% of the increase.[77] Foreign debt also grew substantially under Pinochet, rising 300% between 1974 and 1988.[36]

Under these new policies, the rate of inflation grew to twice what it was at the peak of Allende's presidency.[78]

1973-1982

Chile's main industry, copper mining, remained in government hands, with the 1980 Constitution declaring them "inalienable," [38] but new mineral deposits were open to private investment.[38] Capitalist involvement was increased, the Chilean pension system and healthcare were privatized, and Superior Education was also placed in private hands. One of the junta's economic moves was fixing the exchange rate in the early 1980s, leading to a boom in imports and a collapse of domestic industrial production; this together with a world recession caused a serious economic crisis in 1982, where GDP plummeted by 14%, and unemployment reached 33%. At the same time, a series of massive protests were organized, trying to cause the fall of the regime, which were efficiently repressed.

Deflation policy

Chronic inflation had plagued the Chilean economy for decades when Pinochet took power, and was threatening to become hyperinflation. Between September 1973 and October 1975, the consumer price index rose over 3,000%. In order to combat this persistent problem and pave the way for economic growth, the Chicago Boys recommended dramatic cuts in social services.[35] The junta put the group's recommendations into effect, and cumulative cuts in health funding totaled 60% between 1973 and 1988.

The cuts caused a significant rise in many preventable diseases and mental health problems. These included rises in typhoid (121 percent), viral hepatitis, and the frequency and seriousness of mental ailments among the unemployed.[79]

Exchange rate depreciations and cutbacks in government spending produced a depression. Industrial and agricultural production declined. Massive unemployment, estimated at 25% in 1977 (it was only 3% in 1972), and continuing inflation eroded the living standard of workers and many members of the middle class to subsistence levels. The under-employed informal sector also mushroomed in size.

1982-1990

After the economic crisis of 1982, Hernan Buchi became Minister of Finance from 1985 to 1989. He allowed the peso to float and reinstated restrictions on the movement of capital in and out of the country. He introduced banking legislation, simplified and reduced the corporate tax. Chile pressed ahead with privatizations, including public utilities plus the re-privatization of companies that had returned to the government during the 1982–1983 crisis.

Foreign relations

Pinochet with his Argentine counterpart, Jorge Rafael Videla

Pinochet with his Argentine counterpart, Jorge Rafael Videla Further information: Foreign relations of Chile

Further information: Foreign relations of ChileHaving come to power with the self-proclaimed mission of fighting communism, Pinochet found common cause with the military dictatorships of Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and later, Argentina. The six countries eventually formulated a plan that became known as Operation Condor, in which one country's security forces would target active Marxist subversives, guerrillas, and their alleged sympathizers in the allied countries.[80] Pinochet's government received tacit approval and material support from the United States. The exact nature and extent of this support is disputed. (See U.S. role in 1973 Coup, U.S. intervention in Chile and Operation Condor for more details.) It is known, however, that the American Secretary of State at the time, Henry Kissinger, practiced a policy of supporting coups in nations which the United States viewed as leaning toward Communism.[81]

The new junta quickly broke off the diplomatic relations with Cuba that had been established under the Allende government. Shortly after the junta came to power, several communist countries, including the Soviet Union, North Korea, North Vietnam, East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Yugoslavia, severed diplomatic relations with Chile (however, Romania and the People's Republic of China both continued to maintain diplomatic relations with Chile).[82] The government broke diplomatic relations with Cambodia in January 1974[83] and renewed ties with South Korea in October 1973 and with South Vietnam in March 1974.[84] Pinochet attended the funeral of General Francisco Franco, dictator of Spain from 1936–1975, in late 1975.

Chile was on the brink of being invaded by Argentina (also ruled by a military government) as the Argentina Junta started the Operation Soberania on 22 December 1978 because of the strategic Picton, Lennox and Nueva islands at the southern tip of South America on the Beagle Canal. A full-scale war was prevented only by the call off of the operation by Argentina due to military and political reasons.[85] But the relations remained tense as Argentina invaded the Falklands (Operation Rosario). Chile along with Colombia, were the only countries in South America criticized the use of force by Argentina in its war with the U.K. over the Falkland Islands. Chile actually helped the United Kingdom during the war. The two countries (Chile and Argentina) finally agreed to papal mediation over the Beagle canal that finally ended in the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984 between Chile and Argentina (Tratado de Paz y Amistad). Chilean sovereignty over the islands and Argentinian east of the surrounding sea is now undisputed.

On 1980, Chile's relationship with the Philippines, then a dictatorship under Ferdinand Marcos became strained when that country, due to U.S. pressure rejected to allow Pinochet's plane to land in the country, even though Marcos have invited the General to visit the country. Marcos' move was under U.S. guidelines which sought to isolate Pinochet's regime.[86]

Relations between the two countries were restored only on 1986 when Corazon Aquino assumed the presidency of the Philippines after Marcos was ousted in a non-violent revolution, the People Power Revolution.

Relationship with the U.S.

Further information: United States intervention in ChileThe U.S. provided material support to the military regime after the coup, although criticizing it in public. A document released by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 2000, titled "CIA Activities in Chile", revealed that the CIA actively supported the military junta after the overthrow of Allende and that it made many of Pinochet's officers into paid contacts of the CIA or U.S. military, even though some were known to be involved in human rights abuses.[87]

The U.S. was significantly friendlier with Pinochet than it had been with Allende, and continued to give the junta substantial economic support between the years 1973–1979, while simultaneously expressing opposition to the junta's repression in international forums such as the United Nations. The U.S. went beyond verbal condemnation in 1976, after the murder of Orlando Letelier in Washington D.C., when it placed an embargo on arms sales to Chile that remained in effect until the restoration of democracy in 1989. Presumably, with international concerns over Chilean internal repression and previous American hostility and intervention regarding the Allende government, the U.S. did not want to be seen as an accomplice in the junta's "security" activities. Prominent U.S. allies Britain, France, and West Germany did not block arms sales to Pinochet, benefitting from the lack of American competition.[88][dubious ]

Relationship with the U.K.

Chile was officially neutral during the Falkland Islands conflict[clarification needed], but the Chilean Westinghouse long range radar deployed in southern Chile gave the British task force early warning of Argentinian air attacks, which allowed British ships and troops in the war zone to take defensive action.[89] Margaret Thatcher has said that the day the radar was taken out of service for overdue maintenance was the day Argentinian figher-bombers bombed the troopships Sir Galahad and Sir Tristram, leaving approximately 50 dead and 150 wounded.[90] According to Chilean Junta and former Air Force commander Fernando Matthei, Chilean support included military intelligence gathering, radar surveillance, British aircraft operating with Chilean colours and the safe return of British special forces, among other things.[91] In April and May 1982, a squadron of mothballed RAF Hawker Hunter fighter bombers departed for Chile, arriving on 22 May and allowing the Chilean Air Force to reform the No. 9 "Las Panteras Negras" Squadron. A further consignment of three frontier surveillance and shipping reconnaissance Canberras left for Chile in October. Some authors suggest that Argentina might have won the war had she been allowed to employ the VIth and VIIIth Mountain Brigades which remained sitting up in the Andes mountain chain.[92] Pinochet subsequently visited Margaret Thatcher for tea on more than one occasion.[93] Pinochet's controversial relationship with Thatcher led Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair to mock Thatcher's Conservatives as "the party of Pinochet" in 1999.

French support

Further information: Operation CondorAlthough France received many Chilean political refugees, it also secretly collaborated with Pinochet. French journalist Marie-Monique Robin has shown how Valéry Giscard d'Estaing's government secretly collaborated with Videla's junta in Argentina and with Augusto Pinochet's regime in Chile.[94]

Green deputies Noël Mamère, Martine Billard and Yves Cochet on September 10, 2003 requested a Parliamentary Commission on the "role of France in the support of military regimes in Latin America from 1973 to 1984" before the Foreign Affairs Commission of the National Assembly, presided by Edouard Balladur. Apart of Le Monde, newspapers remained silent about this request.[95] However, deputy Roland Blum, in charge of the Commission, refused to hear Marie-Monique Robin, and published in December 2003 a 12 pages report qualified by Robin as the summum of bad faith. It claimed that no agreement had been signed, despite the agreement found by Robin in the Quai d'Orsay [96][97]

When then Minister of Foreign Affairs Dominique de Villepin traveled to Chile in February 2004, he claimed that no cooperation between France and the military regimes had occurred.[98]

Foreign aid

The previous drop in foreign aid during the Allende years was immediately reversed following Pinochet's ascension; Chile received USD $322.8 million in loans and credits in the year following the coup.[99] There was considerable international condemnation of the military regime's human rights record, a matter that the United States expressed concern over as well after Orlando Letelier's 1976 assassination in Washington DC.(Kennedy Amendment, later International Security Assistance and Arms Export Control Act of 1976).

Cuban involvement

After the Chilean military coup in 1973, Castro promised Chilean revolutionaries "all the aid in Cuba's power to provide." Throughout the 1970s, MIR guerrillas and several hundred Chilean exiles received military training in Cuba.[100] Once their training was completed, Cuba helped the guerrillas return to Chile, providing false passports and false identification documents. Cuba's official newspaper, Granma, boasted in February 1981 that the "Chilean Resistance" had successfully conducted more than 100 "armed actions" throughout Chile in 1980. By late 1980, at least 100 highly trained MIR guerrillas had reentered Chile and the MIR began building a base for future guerrilla operations in Neltume, a mountainous forest region in the extreme south of Chile. In a massive operation spearheaded by Chilean Army Para-Commandos, security forces involving some 2,000 troops, were forced to deploy in the Neltume mountains from June to November 1981, where they destroyed two MIR bases, seizing large caches of munitions and killing a number of MIR commandos. In 1986, Chilean security forces discovered 80 tons of munitions, including more than three thousand M-16 rifles and more than two million rounds of ammunition, at the tiny fishing harbor of Carrizal Bajo, smuggled ashore from Cuban fishing trawlers off the coast of Chile.[101] The operation was overseen by Cuban naval intelligence, and also involved the Soviet Union.

Plebiscite and return to civilian rule

Main article: Chilean transition to democracyAccording to the transitional provisions of the 1980 Constitution, a plebiscite was scheduled for October 5, 1988, to vote on a new eight-year presidential term for Pinochet. The Constitutional Tribunal ruled that the plebiscite should be carried out as stipulated by the Law of Elections. That included an "Electoral Space" during which all positions, in this case two, Sí (yes), and No, would have two free slots of equal and uninterrupted TV time, simultaneously broadcast by all TV channels, with no political advertising outside those spots. The allotment was scheduled in two off-prime time slots: one before the afternoon news and the other before the late-night news, from 22:45 to 23:15 each night (the evening news was from 20:30 to 21:30, and prime time from 21:30 to 22:30). The opposition No campaign, headed by Ricardo Lagos, produced colorful, upbeat programs, telling the Chilean people to vote against the extension of the presidential term. Lagos, in a TV interview, pointed his index finger towards the camera and directly called on Pinochet to account for all the "disappeared" persons. The Sí campaign did not argue for the advantages of extension, but was instead negative, claiming that voting "no" was equivalent to voting for a return to the chaos of the UP government.

Pinochet lost the 1988 referendum, where 55% of the votes rejected the extension of the presidential term, against 43% for "Sí", and, following the constitutional provisions, he stayed as President for one more year. Open presidential elections were held on December 1989, at the same time as congressional elections that would have taken place in either case. Pinochet left the presidency on March 11, 1990 and transferred power to political opponent Patricio Aylwin, the new democratically elected president. Due to the same transitional provisions of the constitution, Pinochet remained as Commander-in-Chief of the Army, until March 1998.

Legacy

Following the restoration of Chilean democracy and during the successive administrations that followed Pinochet, the Chilean economy has prospered, and today the country is considered a Latin American success story. Unemployment stands at 7% as of 2007, with poverty estimated at 18.2% for the same year, both relatively low for the region. [13]

Pinochet's supporters claim that Pinochet saved Chile from turning to Communism, even going as far as to call him the country's second liberator. They also contend that the three successive administrations following him contributed to Chile's economic success by maintaining and continuing the reforms initiated by the junta Opponents have criticized the neoliberal policies enacted by the junta, as well as its human rights abuses.

The "Chilean Variation" has been seen as a potential model for nations that fail to achieve significant economic growth.[14] The latest is Russia, for whom David Christian warned in 1991 that "dictatorial government presiding over a transition to capitalism seems one of the more plausible scenarios, even if it does so at a high cost in human rights violations."[102]

On his 91st birthday in 2006, in a public statement to supporters, Pinochet for the first time claimed to accept "political responsibility" for what happened in Chile under his regime, though he still defended his 1973 coup against Salvador Allende. In a statement read by his wife Lucia Hiriart, he said, Today, near the end of my days, I want to say that I harbour no rancour against anybody, that I love my fatherland above all. ... I take political responsibility for everything that was done.[103] Despite this statement, Pinochet always refused to be confronted to Chilean justice, claiming that he was senile. He died in 2006 while indicted on human rights and corruption charges, but without having been sentenced.

Allegations of State Terrorism

Prof. Michael Stohl, and Prof. George A. López have accused US of State Terrorism for having instigated the coup d’état against elected Socialist President Salvador Allende of Chile.[104]

In The State as Terrorist: The Dynamics of Governmental Violence and Repression, Prof. Michael Stohl writes:In addition to non-terroristic strategies . . . the United States embarked on a program to create economic and political chaos in Chile . . . After the failure to prevent Allende from taking office, efforts shifted to obtaining his removal. Money for the CIA's destabilization of Chilean society, included, financing and assisting opposition groups and right-wing terrorist paramilitary groups such as Patria y Libertad (Fatherland and Liberty)

Prof. Gareau writes:

Washington's training of thousands of military personnel from Chile, who later committed state terrorism, again makes Washington eligible for the charge of accessory before the fact to state terrorism. The CIA’s close relationship, during the height of the terror to Contreras, Chile's chief terrorist (with the possible exception of Pinochet himself), lays Washington open to the charge of accessory during the fact

Prof. Gareau argues that the fuller extent involved the U.S. co-ordinating counterinsurgency warfare among all Latin American countries:

Washington's service as the overall co-ordinator of state terrorism in Latin America demonstrates the enthusiasm with which Washington played its role as an accomplice to state terrorism in the region. It was not a reluctant player. Rather it not only trained Latin American governments in terrorism and financed the means to commit terrorism; it also encouraged them to apply the lessons learned to put down what it called “the communist threat”. Its enthusiasm extended to co-ordinating efforts to apprehend those wanted by terrorist states who had fled to other countries in the region . . . The evidence available leads to the conclusion that Washington’s influence over the decision to commit these acts was considerable.[105] Given that they knew about the terrorism of this régime, what did the élites in Washington during the Nixon and Ford administrations do about it? The élites in Washington reacted by increasing U.S. military assistance and sales to the state terrorists, by covering up their terrorism, by urging U.S. diplomats to do so also, and by assuring the terrorists of their support, thereby becoming accessories to state terrorism before, during, and after the fact[106]

Thomas Wright identifies Chile as an example of open State Terrorism without a civilian governance façade. In State Terrorism and Latin America: Chile, Argentina, and International Human Rights, history professor Thomas Wright argues:

Unlike their Brazilian counterparts, they did not embrace state terrorism as a last recourse; they launched a wave of terrorism on the day of the coup. In contrast to the Brazilians and Uruguayans, the Chileans were very public about their objectives and their methods; there was nothing subtle about rounding up thousands of prisoners, the extensive use of torture, executions following sham court-marshal, and shootings in cold blood. After the initial wave of open terrorism, the Chilean armed forces constructed a sophisticated apparatus for the secret application of state terrorism that lasted until the dictatorship’s end . . . The impact of the Chilean coup reached far beyond the country’s borders. Through their aid in the overthrow of Allende and their support of the Pinochet dictatorship, President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, sent a clear signal to all of Latin America that anti-revolutionary régimes employing repression, even state terrorism, could count on the support of the United States. The U.S. government, in effect, gave a green light to Latin America’s right wing and its armed forces to eradicate the Left, and use repression to erase the advances that workers — and in some countries, campesinos — had made through decades of struggle. This ‘September 11 effect’ was soon felt around the hemisphere[107]

Prof. Gareau concludes:

The message for the populations of Latin American nations, and particularly the Left opposition, was clear: the United States would not permit the continuation of a Socialist government, even if it came to power in a democratic election and continued to uphold the basic democratic structure of that society[106]

Additional information

See also

- Caravan of Death

- Chilean political scandals

- Rettig Report

- Valech Report

- Operation Condor

References

- Christian, D. (1992). "Perestroika and World History", Australian Slavonic and East European studies, 6(1), pp. 1–28.

- Falcoff, M. (2003). "Cuba: The Morning After", p. 26. AEI Press, 2003.

- Petras, J., & Vieux, S. (1990). "The Chilean 'Economic Miracle': An Empirical Critique", Critical Sociology, 17, pp. 57–72.

- Roberts, K.M. (1995). "From the Barricades to the Ballot Box: Redemocratization and Political Realignment in the Chilean Left", Politics & Society, 23, pp. 495–519.

- Schatan, J. (1990). "The Deceitful Nature of Socio-Economic Indicators". Development, 3-4, pp. 69–75.

- Sznajder, M. (1996). "Dilemmas of economic and political modernisation in Chile: A jaguar that wants to be a puma", Third World Quarterly, 17, pp. 725–736.

- Valdes, J.G. (1995). Pinochet's economists: The Chicago School in Chile, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Steve Anderson Body of Chile's Former President Frei May Be Exumed, The Santiago Times, April 5, 2005

Footnotes

- ^ John Wiley Lecture. Between Pinochet and Kropotkin: state terror, human rights and the geographers

- ^ Johan Steyn. The Guardian. April 22, 2006. This All-Powerful Government is Prone to Creeping Authoritarianism

- ^ The Bloody End of a Marxist Dream. Time Magazine. 24 September 1973.

- ^ [1] Pinochet Forms Panel to Consider Return of Chileans Sent Into Exile

- ^ [2] Radomiro Tomic, político chileno

- ^ [3] 25 CHILEAN SOLDIERS ARRESTED IN BURNING OF US RESIDENT

- ^ Pinochet Is History: But how will it remember him? National Review Symposium, December 11, 2006

- ^ [4] The legacy of human-rights violations in the Southern Cone

- ^ Stern, Steve J.. Remembering Pinochet's Chile. 2004-09-30: Duke University Press. pp. 32, 90, 101, 180–81. ISBN 0-8223-3354-6., accessed 10-24-2006 through Google Books.

- ^ [5] BBC: Finding Chile's disappeared

- ^ Thinking About Terrorism: The Threat to Civil Liberties in a Time of National Emergency, Michael E. Tigar, pp. 37-38, American Bar Association, 2007

- ^ Chile: an Amnesty International report,, p. 16, Amnesty International Publications, 1974.

- ^ [6] El campo de concentración de Pinochet cumple 70 años

- ^ [7] New Information on the Murders of U.S. Citizens Charles Horman and Frank Teruggi by the Chilean Military

- ^ [8] BBC: Caravan of Death

- ^ [9] Valech Report

- ^ Augusto Pinochet's Chile, Diana Childress, p.92, Twenty First century Books, 2009

- ^ Chile en el umbral de los noventa: quince años que condicionan el futuro, Jaime Gazmuri & Felipe Agüero, p. 121, Planeta, 1988

- ^ Chile: One Carrot, Many Sticks, Monday, Aug. 22, 1983.TIME MAGAZINE.

- ^ [10] LIFTING OF PINOCHET'S IMMUNITY RENEWS FOCUS ON OPERATION CONDOR

- ^ Chile since the coup: ten years of repression, Cynthia G. Brown, pp.88-89, Americas Watch, 1983.

- ^ a b Wright, Thomas C.; Oñate Zúñiga, Rody (2007). "Chilean political exile". Latin American Perspectives 34 (4): 31.

- ^ Chilean government to sue disappeared tricksters, Albuquerque Express, 30 December 2008

- ^ A Green Light for The Junta? New York Times. October 28, 1977

- ^ Los Allende: con ardiente paciencia por un mundo mejor, Günther Wessel, P. 155, Editorial TEBAR, 2004

- ^ a b CAIDOS DEL MIR EN DIFERENTE PERIODOS. CEME (CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS MIGUEL ENRIQUEZ).

- ^ Aquellos que todo lo dieron. El Rodriguista, 11 Años de Lucha y Dignidad, 1994

- ^ a b New Chilean Leader Announces Political Pardons. New York Times. March 13, 1990

- ^ Vasallo, Mark (2002). "Truth and Reconciliation Commissions: General Considerations and a Critical Comparison of the Commissions of Chile and El Salvador". The University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 33 (1): 163.

- ^ . CNN. 2008-03-20. http://edition.cnn.com/2008/WORLD/americas/03/20/chile.convictions/index.html.

- ^ Hudson, Rex A., ed. "Chile: A Country Study." GPO for the Library of Congress. 1995. March 20, 2005 http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/cltoc.html

- ^ a b K. Remmer (1998). Public Policy and Regime Consolidation: The First Five Years of the Chilean Junta. pp. 5–55. Journal of the Developing Areas.

- ^ Valenzuela, Arturo (2002). A Nation of Enemies. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 170

- ^ Valenzuela, Arturo (2002). A Nation of Enemies. New York: W. W. Norton. p. 197-8

- ^ a b K. Remmer (1998). The Politics of Neoliberal Economic Reform in South America. 33. pp. 3–29. Studies in Comparative International Development.

- ^ a b c d e f James Petras; Steve Vieux (1990). The Chilean "Economic Miracle": An Empirical Critique. pp. 57–72. Critical Sociology.

- ^ Sznajder, 1996

- ^ a b c d Manuel Riesco, "Is Pinochet dead?", New Left Review n°47, September–October 2007 (English and Spanish)

- ^ [11] Chile under Pinochet: recovering the truth

- ^ Remmer, 1989

- ^ a b Terrorism Review Chile: Change in MIR tactics

- ^ Latin America's Wars: The age of the professional soldier, 1900-2001, Robert L. Scheina, p. 326

- ^ "El terrorismo de los años 70". Archived from the original on 2009-09-03. http://www.analitica.com/va/internacionales/opinion/9892262.asp. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- ^ Los Allende: con ardiente paciencia por un mundo mejor. Günther Wessel, p. 155, Editorial TEBAR, 2004

- ^ Chile's MIR: The Revolutionary Left Movement

- ^ (Informe Rettig. Volume II. Page 605. Chile)

- ^ a b Informe de la Comisión Nacional de Verdad y Reconciliación”, Volume II, Page 605, Santiago, Chile, 1991. (SM, V, Chro)

- ^ Shootout kills 5 in Chile capital. Bangor Daily News. 25 February 1976.

- ^ State Terrorism in Latin America: Chile, Argentina and International Human Rights, Thomas C. Wright, p. 81, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007

- ^ Wilimington Morning Star, July 16, 1980

- ^ Devo Forbes. "Inauguration of President Pinochet for Further Term". Archived from the original on 2009-08-17. http://www.britishcouncil.org/learnenglish-central-history-pinochet.htm. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ Chile: Terrorism still counterproductive. CIA document

- ^ [Miami Herald, August 31, 1983]

- ^ "Despierta chile". Archived from the original on 2009-08-17. http://www.despiertachile.cl/2006/dic06/html/martires.html. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ Bomb Kills Policeman On a Bus in Santiago. The New York Times. 31 March 1984

- ^ Bomb Derails Subway In Chile, Injuring 22. The New York Times. 30 April 1984

- ^ Informe de la Comisión Nacional de Verdad y Reconciliación”, Volume II, Page 680, Santiago, Chile, 1991. (SM, V, Chro)

- ^ Chile under Pinochet: Recovering the truth, Mark Ensalaco, p. 140

- ^ [Miami Herald, November 5, 1984]

- ^ [Miami Herald, December 8, 1985]

- ^ a b Chile Terrorism

- ^ 16 cops hurt in Chile bomb blast. The Miami News. 6 February 1986

- ^ Terrorist Group Profiles, p. 98, US Secretary of Defense, 1989

- ^ Bomb explodes near Chilean palace. The Deseret News. 26 July 1986

- ^ Pinochet S.A.: la base de la fortuna. Ozren Agnic Krstulovic. Page 147. RiL Editores 2006.

- ^ Pinochet's New State of Siege, Time magazine, September 22, 1986

- ^ Informe de la Comisión Nacional de Verdad y Reconciliación”, Volume I, Page 692, Santiago, Chile, 1991. (SM, V, Chro)

- ^ (Informe Rettig. Volume II. Page 695. Chile)

- ^ Chicago Tribune, August 12, 1990

- ^ [Miami Herald, March 5, 1991]

- ^ Chile: coup anniversary brings heavy repression, 23 September 1998

- ^ Shooting, looting and arson on Chile September 11 anniversary

- ^ Policeman killed on coup anniversary, September 13, 2007

- ^ Unos 31 heridos y 234 detenidos en aniversario del golpe militar en Chile

- ^ Levante. Una noche de disturbios se salda con 206 detenidos y más de una veintena de heridos en el país andino

- ^ MIR in Chile: ‘Expropriation is a people’s right’

- ^ Schatan, 1990

- ^ Andre, Gunder Frank (1976). Economic Genocide in Chile. Spokesman Books.. ISBN 978-0-85124-160-9. p. 100

- ^ Contreras, 1986

- ^ Operation Condor

- ^ [12] The Kissinger Telcons: Kissinger Telcons on Chile

- ^ J. Samuel Valenzuela and Arturo Valenzuela (eds.), Military Rule in Chile: Dictatorship and Oppositions, p. 317

- ^ El Mercurio, 20 January 1974

- ^ El Mercurio, 6 April 1975

- ^ See Alejandro Luis Corbacho "Predicting the probability of war during brinkmanship crisis: The Beagle and the Malvinas conflicts" http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1016843 about the reasons of the call off (p.45): The newspaper Clarín explained some years later that such caution was based, in part, on military concerns. In order to achieve a victory, certain objectives had to be reached before the seventh day after the attack. Some military leaders considered this not enough time due to the difficulty involved in transportation through the passes over the Andean Mountains. and in cite 46: According to Clarín, two consequences were feared. First, those who were dubious feared a possible regionalization of the conflict. Second, as a consequence, the conflict could acquire great power proportions. In the first case decisionmakers speculated that Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Brazil might intervene. Then the great powers could take sides. In this case, the resolution of the conflict would depend not on the combatants, but on the countries that supplied the weapons.

- ^ Helen Spooner, Soldiers in a narrow land: the Pinochet regime in Chile, url

- ^ Peter Kornbluh, CIA Acknowledges Ties to Pinochet’s Repression Report to Congress Reveals U.S. Accountability in Chile, Chile Documentation Project, National Security Archive, September 19, 2000. Accessed online November 26, 2006.

- ^ Falcoff, 2003

- ^ Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Speech on Pinochet at the Conservative Party Conference. October 6 1999.

- ^ The Falklands Conflict Part 5 - Battles of Goose Green & Stanley HMFORCES.CO.UK

- ^ Mercopress. September 3rd 2005.

- ^ Nicholas van der Bijl and David Aldea, 5th Infantry Brigade in the Falklands , page 28, Leo Cooper 2003

- ^ "Pinochet death 'saddens' Thatcher". BBC News. December 11, 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk_politics/6167351.stm. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ^ Conclusion of Marie-Monique Robin's Escadrons de la mort, l'école française (French)/ Watch here film documentary (French, English, Spanish)

- ^ MM. Giscard d'Estaing et Messmer pourraient être entendus sur l'aide aux dictatures sud-américaines, Le Monde, September 25, 2003 (French)

- ^ « Série B. Amérique 1952-1963. Sous-série : Argentine, n° 74. Cotes : 18.6.1. mars 52-août 63 ».

- ^ RAPPORT FAIT AU NOM DE LA COMMISSION DES AFFAIRES ÉTRANGÈRES SUR LA PROPOSITION DE RÉSOLUTION (n° 1060), tendant à la création d'une commission d'enquête sur le rôle de la France dans le soutien aux régimes militaires d'Amérique latine entre 1973 et 1984, PAR M. ROLAND BLUM, French National Assembly (French)

- ^ Argentine : M. de Villepin défend les firmes françaises, Le Monde, February 5, 2003 (French)

- ^ Petras & Morley, 1974

- ^ Cuba's Renewed Support of Violence in Latin America

- ^ The Day Pinochet Nearly Died.

- ^ Christian, 1992

- ^ (BBC)

- ^ "The State as Terrorist: The Dynamics of Governmental Violence and Repression" by Prof. Michael Stohl, and Prof. George A. López; Greenwood Press, 1984. Page 51

- ^ State Terrorism and the United States: From Counterinsurgency to the War on Terrorism by Frederick H. Gareau, Page78-79.

- ^ a b State Terrorism and the United States: From Counterinsurgency to the War on Terrorism by Frederick H. Gareau, Page 87.

- ^ Wright, Thomas C. State Terrorism and Latin America: Chile, Argentina, and International Human Rights, Rowman & Littlefield, page 29

External links

- Literature and Torture in Pinochet's Chile

- Criminals of the military dictatorship : Augusto Pinochet

Chile topics

Chile topicsHistory Timeline · First inhabitants · Captaincy General of Chile · Arauco War · Independence · Parliamentary Era (1891-1925) · Presidential Republic (1925–1973) · Presidency of Salvador Allende · 1973 coup · Pinochet regime · Transition to democracyLaw Constitution · Supreme Court · Civil Code · Law enforcement · Nationality law · Copyright law · Passport · Human rights · LGBT rightsPolitics Geography Regions · Provinces · Natural regions · Cities · Climate · Geology · Islands · Rivers · Extreme points · National ParksEconomy History · Peso · Central Bank · Stock Exchange · Companies · Agriculture · Communications · Transport · TourismMilitary Demographics Culture Other topics Healthcare · Education · Notable Chileans · International rankings · Holidays · Water supply and sanitation · Women · Beauty pageantsPortal · WikiProject Augusto Pinochet Life and politics Policies Perceptions Family 1973 Chilean coup d'état Background Events Participants Aftermath Controversies Categories:- Chile under Augusto Pinochet

- 1990 disestablishments

- Military dictatorship

- Former polities of the Cold War

- 1970s in Chile

- 1980s in Chile

- Politics of Chile

- Augusto Pinochet

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.