- Meter (music)

-

Musical and lyric metre.

Musical and lyric metre.

Meter or metre is a term that music has inherited from the rhythmic element of poetry (Scholes 1977; Latham 2002) where it means the number of lines in a verse, the number of syllables in each line and the arrangement of those syllables as long or short, accented or unaccented (Scholes 1977; Latham 2002). Hence it may also refer to the pattern of lines and accents in the verse of a hymn or ballad, for example, and so to the organization of music into regularly recurring measures or bars of stressed and unstressed "beats", indicated in Western music notation by a time signature and bar-lines.

The terminology of western music is notoriously imprecise in this area (Scholes 1977). MacPherson (1930, 3) preferred to speak of "time" and "rhythmic shape", Imogen Holst (1963, 17) of "measured rhythm". However, London has written a book about musical metre, which "involves our initial perception as well as subsequent anticipation of a series of beats that we abstract from the rhythm surface of the music as it unfolds in time" (London 2004, 4).

This "perception" and "abstraction" of rhythmic measure is the foundation of human instinctive musical participation, as when we divide a series of identical clock-ticks into "tick-tock-tick-tock" (Scholes 1977). "Rhythms of recurrence" arise from the interaction of two levels of motion, the faster providing the pulse and the slower organizing the beats into repetitive groups (Yeston 1976, 50–52). "Once a metric hierarchy has been established, we, as listeners, will maintain that organization as long as minimal evidence is present" (Lester 1986, 77).

Contents

Metric structure

The definition of a musical meter requires the identification of repeating patterns of accent forming a "pulse-group" that corresponds to the poetic foot. Normally such pulse-groups are defined by taking the accented beat as the first and counting the pulses until the next accent (MacPherson 1930, 5; Scholes 1977). Normally, even the most complex of meters may be broken down into a chain of duple and triple pulses (MacPherson 1930, 5; Scholes 1977). The level of musical organisation implied by musical meter, therefore, includes the most elementary levels of musical form (MacPherson 1930, 3).

The general classifications of rhythm metrical rhythm, measured rhythm, and free rhythm may be distinguished in all aspects of temporality (Cooper 1973, 30). Metrical rhythm, by far the most common in Western music, is where each time value is a multiple or fraction of a fixed unit (beat, see paragraph below) and normal accents re-occur regularly providing systematical grouping (measures, divisive rhythm), measured rhythm is where each time value is a multiple or fraction of a specified time unit but there are not regularly recurring accents (additive rhythm), and free rhythm is where there is neither (Cooper 1973, 30). Some music, including chant, has freer rhythm, like the rhythm of prose compared to that of verse (Scholes 1977). Some music, such as some graphically scored works since the 1950s and non-European music such as Honkyoku repertoire for shakuhachi, may be considered ametric (Karpinski 2000, 19). Senza misura is an Italian musical term for "without meter", meaning to play without a beat, using time to measure how long it will take to play the bar (Forney and Machlis 2007,[page needed]).

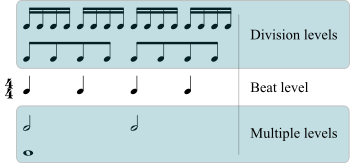

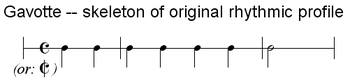

Metric structure includes meter, tempo, and all rhythmic aspects which produce temporal regularity or structure, against which the foreground details or durational patterns of any piece of music are projected (Wittlich 1975, chapt. 3). Metric levels may be distinguished: the beat level is the metric level at which pulses are heard as the basic time unit of the piece. Faster levels are division levels, and slower levels are multiple levels (Wittlich 1975, chapt. 3). A rhythmic unit is a durational pattern which occupies a period of time equivalent to a pulse or pulses on an underlying metric level.

Types

Simple meter

Simple metre or simple time is a metre in which each beat of the measure divides naturally into two equal parts, rather than three which gives a compound metre. For example, in the time signature 3/4, each measure contains three crotchet (quarter note) beats, and each of those beats divides into two quavers (eighth notes), making it a simple metre. More specifically, it is simple triple because there are three beats in each measure; duple (two beats) or quadruple (four) are also common metres, with other numbers being less usual.

Compound meter

Compound meter, compound metre, or compound time (chiefly British variation), is a time signature or meter in which each beat is divided into three or more parts, or two uneven parts.[citation needed] In Western music, the predominant form of compound meter is the division into three parts; but more parts are possible, and frequently used, for example, in Balkan music; some examples are given in the article Bulgarian dances.[citation needed]

Compound meters are written with a time signature showing the number of divisions of the beat in each measure. For example, compound duple (two beats, each divided into three) is written as a time signature with a numerator of six, such as 6/8. A time signature of 3/4 would also contain six quavers in the measure, but by convention it is understood that 3/4 refers to three crotchet beats, while 6/8 refers to two beats divided into three.

Examples of compound meter:

- 6/8 (compound duple meter) has two beats divided into three equal parts, i.e., a primary accent on the first quaver, and a subordinate accent on the fourth quaver.

- 9/8 (compound triple meter) has three beats divided into three parts, i.e., a primary accent on the first quaver, and subordinate accents on the fourth and seventh quavers.

- 12/8 (compound quadruple meter) has four beats divided into three equal parts, i.e., a primary accent on the first quaver, a secondary accent on the seventh quaver, and subordinate accents on the fourth and tenth quavers.

Although 3/4 and 6/8 are not to be confused, they use measures of the same length, so it is easy to "slip" between them just by shifting the location of the accents. This interpretational switch has been exploited, for example, by Leonard Bernstein, in the song "America" from West Side Story, as can be heard in the prominent motif:

Some works with compound meter:

- The Irish slip jig is characterized by being in 9/8 time.

Counter-examples, not in compound meter

Compound meter divided into three parts could theoretically be transcribed into musically equivalent simple meter using triplets. Likewise, simple meter can be shown in compound through duples. In practice, however, this is rarely done because it disrupts conducting patterns when the Tempo changes. When conducting in 6/8, conductors typically provide two beats per measure. Where the tempo is slow, however, all six beats may be performed.

Compound time is associated with "lilting" and dance-like qualities. Folk dances often use compound time. Many Baroque dances are often in compound time: some gigues, the courante, and sometimes the passepied and the siciliana.

Meter in song

The concept of meter in music derives in large part from the poetic meter of song and includes not only the basic rhythm of the foot, pulse-group or figure used but also the rhythmic or formal arrangement of such figures into musical phrases (lines, couplets) and of such phrases into melodies, passages or sections (stanzas, verses) to give what Holst (1963, 18) calls "the time pattern of any song" (See also: Form of a musical passage).

Traditional and popular songs may draw heavily upon a limited range of meters, leading to interchangeability of melodies. Early hymnals commonly did not include musical notation but simply texts that could be sung to any tune known by the singers that had a matching meter. For example The Blind Boys of Alabama rendered the hymn Amazing Grace to the setting of The Animals' version of the folk song The House of the Rising Sun. This is possible because the texts share a popular basic four-line (quatrain) verse-form called ballad meter or, in hymnals, common meter, the four lines having a syllable-count of 8:6:8:6 (Hymns Ancient and Modern Revised), the rhyme-scheme usually following suit: ABAB. There is generally a pause in the melody in a cadence at the end of the shorter lines so that the underlying musical meter is 8:8:8:8 beats, the cadences dividing this musically into two symmetrical "normal" phrases of four measures each (MacPherson, 14).

Two-fold, four-fold and eight-fold division and multiplication of phrases into measures and of phrases into passages is indeed "common" and "normal"—the above arrangement is typical of the Baroque suite and the Bach chorale—but it is far from universal. "God Save the Queen", for example, has six three-beat measures in its first phrase and eight in the second yet it still achieves symmetry. A Twelve-bar blues has three lines, not two or four, of four measures each.[citation needed]

In some regional music, for example Balkan music (like Bulgarian music, and the Macedonian 3+2+2+3+2 meter), a wealth of irregular or compound meters are used. Other terms for this are "additive meter" (London 2001, §I.8) and "imperfect meter" (Gardner 1964,[page needed]).

Meter in dance music

Meter is often essential to any style of dance music, such as the waltz or tango, that has instantly recognizable patterns of beats built upon a characteristic tempo and measure. The Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing (1983) defines the tango, for example, as to be danced in 2/4 time at approximately 66 beats per minute.

The basic slow step forwards or backwards, lasting for one beat, is called a "slow", so that a full "right-left" step is equal to one 2/4 measure.

But step-figures such as turns, the corte and walks-in also require "quick" steps of half the duration, each entire figure requiring 3-6 "slow" beats. Such figures may then be "amalgamated" to create a series of movements that may synchronise to an entire musical section or piece. This can be thought of as an equivalent of prosody.

Meter in classical music

In music of the common practice period (about 1600–1900), there are four different families of time signature in common use:

- Simple duple – two or four beats to a bar, each divided by two, the top number being "2" or "4" (2/4, 2/8, 2/2 … 4/4, 4/8, 4/2 …). When there are four beats to a bar, it is alternatively referred to as "quadruple" time.

- Simple triple (

3/4 (help·info)) – three beats to a bar, each divided by two, the top number being "3" (3/4, 3/8, 3/2 …)

3/4 (help·info)) – three beats to a bar, each divided by two, the top number being "3" (3/4, 3/8, 3/2 …) - Compound duple - two beats to a bar, each divided by three, the top number being "6" (6/8, 6/16, 6/4 …)

- Compound triple - three beats to a bar, each divided by three, the top number being "9" (9/8, 9/16, 9/4)

If the beat is divided into two the meter is simple, if divided into three it is compound. If each measure is divided into two it is duple and if into three it is triple. Some people also label quadruple, while some consider it as two duples. Any other division is considered additively, as a measure of five beats may be broken into duple+triple (12123) or triple+duple (12312) depending on accent. However, in some music, especially at faster tempos, it may be treated as one unit of five.

Changing meter

In twentieth century concert music, it became more common to switch meter—the end of Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring is an example. A metric modulation is a modulation from one metric unit or meter to another. The use of asymmetrical rhythms also became more common: such meters include quintuple as well as more complex additive meters along the lines of 2+2+3 time, where each bar has two 2-beat units and a 3-beat unit with a stress at the beginning of each unit. Similar meters are used in various folk music as well as some music by Philip Glass. Additive meters may be conceived either as long, irregular meters or as constantly changing short meters.

Hypermeter

Hypermeter is large-scale meter (as opposed to surface-level meter) created by hypermeasures which consist of hyperbeats (Stein 2005, 329). "Hypermeter is meter, with all its inherent characteristics, at the level where measures act as beats." (Neal 2000, 115) For example, the four-bar hypermeasure is the prototypical structure for country music, in and against which country songs work (Neal 2000, 115). The term was coined by Cone (1968) while London (2004, 19) asserts that there is no perceptual distinction between meter and hypermeter. Lee (1985) and Middleton have described musical meter in terms of deep structure, using generative concepts to show how different meters (4/4, 3/4, etc.) generate many different surface rhythms. For example the first phrase of The Beatles' "A Hard Day's Night", without the syncopation, may be generated from its meter of 4/4 (Middleton 1990, 211):

4/4 4/4 4/4 / \ / \ / \ 2/4 2/4 2/4 2/4 2/4 2/4 | / \ | | | \ | 1/4 1/4 | | | \ | / \ / \ | | | | 1/8 1/8 1/8 1/8 | | | | | | | | | | | It's been a hard days night...

The syncopation may then be added, moving "night" forward one eighth note, and the first phrase is generated (

Play (help·info)).

Play (help·info)).Polymeter

Although sometimes used synonymously (Anon. [2001]), polymeter is the use of two or more metric frameworks (time signatures) simultaneously, while polyrhythm refers to the simultaneous use of two or more different patterns, which may be in the same time-signature (Anon. 1999).

Research into the perception of polymeter shows that listeners often either extract a composite pattern that is fitted to a metric framework, or focus on one rhythmic stream while treating others as "noise". This is consistent with the Gestalt psychology tenet that "the figure-ground dichotomy is fundamental to all perception" (Boring 1942, 253; London 2004, 49-50). In the music, the two meters will meet each other after a specific number of beats. For example, a 3/4 meter and 4/4 meter will meet after 12 beats.

In "Toads Of The Short Forest" (from the album Weasels Ripped My Flesh), composer Frank Zappa explains: "At this very moment on stage we have drummer A playing in 7/8, drummer B playing in 3/4, the bass playing in 3/4, the organ playing in 5/8, the tambourine playing in 3/4, and the alto sax blowing his nose" (Mothers of Invention 1970). "Touch And Go", a hit single by The Cars, has polymetric verses, with the drums and bass playing in 5/4, while the guitar, synthesizer, and vocals are in 4/4 (the choruses are entirely in 4/4) (The Cars 1981, 15). The Swedish metal band Meshuggah makes frequent use of polymeters, with unconventionally-timed rhythm figures cycling over a 4/4 base (Pieslak, 2007).

Examples of various meter sound samples

- sample of how

1/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm.

1/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm. - sample of how

2/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm.

2/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm. - sample of how

3/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm.

3/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm. - sample of how

4/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm.

4/4 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 90bpm. - sample of how

5/8 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 120bpm.

5/8 meter (help·info) sounds in a tempo of 120bpm.

Sources

- Anon. (1999). "Polymeter." Baker's Student Encyclopedia of Music, 3 vols., ed. Laura Kuhn. New York: Schirmer-Thomson Gale; London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-02-865315-7. Online version 2006, at http://www.enotes.com/music-encyclopedia/polymeter (Accessed 4 April 2009).

- Anon. [2001]. "Polyrhythm". Grove Music Online. (Accessed 4 April 2009)

- The Cars (1981). Panorama (songbook). New York: Warner Bros. Publications Inc.

- Cooper, Paul (1973). Perspectives in Music Theory: An Historical-Analytical Approach. New York: Dodd, Mead. ISBN 0-396-06752-2.

- Forney, Kristine, and Joseph Machlis (2007). The Enjoyment of Music: An Introduction to Perceptive Listening, 10th Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-92885-3 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-393-17410-6 (text w/DVD) ISBN 978-0-393-92888-4 (pbk.) ISBN 978-0-393-10757-9 (DVD)

- Hindemith, Paul (1974). Elementary Training for Musicians, second edition (rev. 1949). Mainz, London, and New York: Schott. ISBN 0-901938-16-5.

- Holst, Imogen (1963). The ABC of Music: A Short Practical Guide to the Basic Essentials of Rudiments, Harmony, and Form'. Benjamin Britten (foreword). London & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0193171031.

- Honing, Henkjan (2002). "Structure and Interpretation of Rhythm and Timing." Tijdschrift voor Muziektheorie 7(3):227–32.pdf

- The Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing (1983). Ballroom Dancing, Hodder and Stoughton.

- Karpinski, Gary S. (2000). Aural Skills Acquisition: The Development of Listening, Reading, and Performing Skills in College-Level Musicians. ISBN 0-19-511785-9.

- Krebs, Harald (2005). "Hypermeter and Hypermetric Irregularity in the Songs of Josephine Lang.". In in Deborah Stein (ed.),. Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517010-5.

- Larson, Steve (2006). "Rhythmic Displacement in the Music of Bill Evans". In Structure and Meaning in Tonal Music: Festschrift in Honor of Carl Schachter, edited by L. Poundie Burstein and David Gagné, 103–22. Harmonologia Series, no. 12. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press. ISBN 1576471128

- Latham, Alison. 2002. "Metre". The Oxford Companion to Music", edited by Alison Latham. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- Lester, Joel (1986). The Rhythms of Tonal Music. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-1282-4.

- London, Justin (2001). "Rhythm". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan Publishers.

- London, Justin (2004). Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516081-9.

- MacPherson, Stewart (1930). Form in Music. London: Joseph Williams Ltd.

- Mothers of Invention, The (1970). Weasels Ripped My Flesh. LP, Bizarre/Reprise MS 2028.

- Neal, Jocelyn, Charles K. Wolfe, and James E. Akenson (eds.) (2000). "Songwriter's Signature, Artist's Imprint: The Metric Structure of a Country Song", Country Music Annual 2000. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0989-2.

- Pieslak, Jonathon (2007). "Re-casting Metal: Rhythm and Meter in the Music of Meshuggah," Music Theory Spectrum 29.

- Scholes, Percy (1977). "Metre" and "Rhythm", in The Oxford Companion to Music, 6th corrected reprint of the 10th ed. (1970), revised and reset, edited by John Owen Ward. London and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-311306-6

- Scruton, Roger (1997). The Aesthetics of Music, p. 25ex2.6. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-816638-9.

- Waters, Keith (1996). "Blurring the Barline: Metric Displacement in the Piano Solos of Herbie Hancock". Annual Review of Jazz Studies 8:19–37.

- Wittlich, Gary E. (ed.) (1975). Aspects of Twentieth-century Music. Englewood Cliffs, N. J.: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0130493465.

- Yeston, Maury (1976). The Stratification of Musical Rhythm. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300018843.

See also

- Time signature

- Wazn

- Tala

- List of musical works in unusual time signatures

- Counting (music)

- Tuplet

- Composite rhythm

External links

- www.oddtimeobsessed.com website and Internet radio dedicated to odd meters in music. (odd time signatures)

- Video samples of polymeters and mixed meters with Bounce Metronome Pro's "Gravity Bounce Conductor"

- Catherine Schmidt-Jones. "Meter in Music". http://cnx.org/content/m12405/latest/. Retrieved 2008-11-10.

Rhythm and meter Additive and divisive · Beat · Composite rhythm · Counting · Cross-beat · Duration · Groove · Meter · Polyrhythm · Pulse · Rhythmic gesture · Rhythmic unit · Swing · Syncopation · Tempo · Time scale · Time signatureMusical notation and development Staff

Notes Accidental (Flat · Natural · Sharp) · Dotted note · Grace note · Note value (Beam · Note head · Stem) · Pitch · Rest · Tuplet · Interval · Helmholtz pitch notation · Letter notation · Scientific pitch notation

Articulation Development Coda · Exposition · Harmony · Melody · Motif · Ossia · Recapitulation · Repetition · Rhythm (Beat · Meter · Tempo) · Theme · Tonality · Atonality

Related Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.