- Thunderball (film)

-

Thunderball

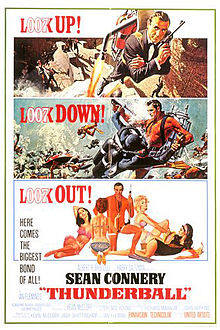

Thunderball film poster by Robert McGinnis & Frank McCarthyDirected by Terence Young Produced by Kevin McClory

Albert R. Broccoli (Executive producer)

Harry Saltzman (Executive producer)Written by Ian Fleming

Kevin McClory

Jack WhittinghamScreenplay by Richard Maibaum

John HopkinsStarring Sean Connery

Claudine Auger

Adolfo Celi

Luciana Paluzzi

Rik Van Nutter

Desmond Llewelyn

Bernard LeeMusic by John Barry

"Thunderball"Cinematography Ted Moore Editing by Peter R. Hunt Studio Danjaq

Eon ProductionsDistributed by United Artists Release date(s) 9 December 1965 (Tokyo, premiere) Running time 130 minutes Country United Kingdom Language English Budget $9 million Box office $141.2 million Thunderball (1965) is the fourth spy film in the James Bond series after Dr. No (1962), From Russia with Love (1963) and Goldfinger (1964), and the fourth to star Sean Connery as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond. It is an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Ian Fleming, which in turn was based on an original screenplay by Jack Whittingham. It was directed by Terence Young with screenplay by Richard Maibaum and John Hopkins.

The film follows Bond's mission to find two NATO atomic bombs stolen by SPECTRE, which holds the world ransom for £100 million in diamonds, in exchange for not destroying an unspecified major city in either England or the United States (later revealed to be Miami). The search leads Bond to the Bahamas, where he encounters Emilio Largo, the card-playing, eye-patch wearing SPECTRE Number Two. Backed by the CIA and Largo's mistress, Bond's search culminates in an underwater battle with Largo's henchmen. The film had a complex production, with four different units and about a quarter of the film consisting of underwater scenes.[1]

Thunderball was associated with a legal dispute in 1961 when former Ian Fleming collaborators Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham sued him shortly after the 1961 publication of the Thunderball novel, claiming he based it upon the screenplay the trio had earlier written in a failed cinematic translation of James Bond. The lawsuit was settled out of court and Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, fearing a rival McClory film, allowed him to retain certain screen rights to the novel's story, plot, and characters.[2]

The film was a success, earning a total of $141.2 million worldwide,[3] exceeding the earnings of the three previous Bond films and breaking box office records on the first weekend of opening in France and Italy. In 1966, John Stears won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects[4] and production designer Ken Adam was also nominated for a BAFTA award.[5] Thunderball is, to date, the most financially successful movie of the series, and, adjusting for inflation, made the equivalent of $966.4 million in 2008 currency. Some critics and viewers showered praise on the film and branded it a welcome addition to the series, while others complained of the repetitively monotonous aquatic action and prolonged length. In 1983, Warner Brothers released a second film adaptation of the novel under the title Never Say Never Again.

Contents

Plot

James Bond - MI6 agent 007 and sometimes simply '007' - attends the funeral of Colonel Jacques Bouvar, a SPECTRE operative (Number 6).[6] Bouvar is alive and disguised as his own widow, but Bond identifies him. Following him to a château, Bond fights and kills him, escaping using a jetpack and Aston Martin DB5.

Bond is sent by M to a clinic to improve his health. While massaged by physiotherapist Patricia Fearing, he notices Count Lippe, a suspicious man with a criminal tattoo (from a Tong). He searches Lippe's room, but is seen leaving by Lippe's clinic neighbour who is bandaged after plastic surgery. Lippe tries to murder Bond with a spinal traction machine, but is foiled by Fearing, whom Bond then seduces. Bond finds a dead bandaged man, François Derval. Derval was a French NATO pilot deployed to fly aboard an Avro Vulcan loaded with two atomic bombs for a training mission. He had been murdered by Angelo, a SPECTRE henchman surgically altered to match his appearance.

Angelo takes Derval's place on the flight, sabotaging the plane and sinking it near the Bahamas. He is then killed by Emilio Largo (SPECTRE No. 2) for trying to extort more money than offered to him. Largo and his henchmen retrieve the stolen atomic bombs from the seabed. All double-0 agents are called to Whitehall and en route, Lippe chases Bond. Lippe is killed by SPECTRE agent Fiona Volpe for failing to foresee Angelo's greed. SPECTRE demands £100 million in white flawless uncut diamonds from NATO in exchange for returning the bombs. If their demands are not met, SPECTRE will destroy a major city in the United States or the United Kingdom. At the meeting, Bond recognises Derval from a photograph. Since Derval's sister, Domino, is in Nassau, Bond asks M to send him there, where he discovers Domino is Largo's mistress.

Bond takes a boat to where Domino is snorkelling. After saving her life, the two have lunch together. Later, Bond goes to a party, where he sees Largo and Domino gambling. Bond enters the game against Largo, and wins. Bond and Domino leave the game and dance together. Bond returns to the Hotel, uses a secret corridor to enter his room and notices someone is also inside. Felix Leiter enters and is silenced by Bond, who finds and disarms a SPECTRE henchman in the bathroom. He releases the henchman, who returns to Largo and is thrown into a pool of sharks.

Bond meets Q, and is issued with a collection of gadgets, including an underwater infrared camera, a distress beacon, underwater breathing apparatus, a flare gun and a Geiger counter. Bond attempts to scuba under Largo's boat but is nearly killed. Bond's assistant Paula is abducted by Largo for questioning and kills herself.

Bond is kidnapped by Fiona, but escapes. He is chased through a Junkanoo celebration and enters the Kiss Kiss club. Fiona finds and attempts to kill him, but is shot by her own bodyguard. Bond and Felix search for the Vulcan, finding it underwater. Bond meets Domino scuba-diving and they have underwater sex. Bond tells her that Largo killed her brother, asking for help finding the bombs. She tells him where to go to replace a henchman on Largo's mission to retrieve them from a submarine. Bond gives her his Geiger counter, asking her to look for them on Largo's ship. She is discovered and captured. Disguised as Largo's henchman, Bond uncovers Largo's plan to destroy Miami Beach.

Bond is discovered, and rescued by Leiter, who orders United States Coast Guard sailors to parachute to the area. After an underwater battle, the henchmen surrender. Largo escapes to his ship, the Disco Volante, which has one of the bombs on board. Largo attempts to escape by jettisoning the rear of the ship. The front section, a hydrofoil, escapes. Bond, also aboard, and Largo fight; Largo is about to shoot him when Domino, freed by Ladislav Kutze, shoots Largo with a harpoon. Bond and Domino jump overboard, the boat runs aground and explodes. A sky hook-equipped U.S. Navy airplane rescues them.

Cast

Main articles: List of James Bond henchmen in Thunderball and List of James Bond allies in Thunderball- Sean Connery as James Bond (007): An MI6 agent assigned to retrieve two stolen nuclear weapons.

- Adolfo Celi as Emilio Largo (voice dubbed by Robert Rietty):[7] Main antagonist. SPECTRE's Number Two, he creates a scheme to steal two atomic bombs.

- Claudine Auger as Dominique "Domino" Derval (voice dubbed by Nikki van der Zyl):[8] Largo's mistress. In early drafts of the screenplay Domino's name was Dominetta Palazzi. When Claudine Auger was cast as Domino the name was changed to Derval to reflect her nationality.[9]

- Luciana Paluzzi as Fiona Volpe: SPECTRE agent, who becomes François Derval's mistress and kills Count Lippe before being sent to Nassau.

- Rik Van Nutter as Felix Leiter: CIA agent who helps Bond.

- Bernard Lee as M: The strict head of MI6.

- Guy Doleman as Count Lippe: SPECTRE agent who tries to kill Bond in the health clinic.

- Martine Beswick as Paula Caplan: Bond's ally in Nassau who is kidnapped by Vargas and Janni.

- Molly Peters as Patricia Fearing: a physiotherapist at the clinic Bond is sent to.[10]

- Earl Cameron as Pinder, Bond and Felix Leiter's assistant in The Bahamas.

- Paul Stassino as François Derval and Angelo Palazzi: Derval a NATO pilot, who is also Domino's brother. He is killed by SPECTRE agent Angelo Palazzi who impersonates him. Palazzi is later killed by Largo.

- Desmond Llewelyn as Q: MI6's "quartermaster" who supplies Bond with multi-purpose vehicles and gadgets useful for the latter's missions.

- Roland Culver as the Home Secretary: The British Foreign Minister who briefs the "00" agents for Operation Thunderball and has doubts about Bond's efficiency.

- Lois Maxwell as Miss Moneypenny: M's secretary and love interest for 007.

- Philip Locke as Vargas: Largo's personal assistant and henchman who according to Largo abstains from alcohol, smoking and sexual intercourse emphasising his devotion as a killer. He is killed by Bond with a spear gun on the beach.

- George Pravda as Ladislav Kutze: Emilio Largo's chief nuclear physicist who aids his boss with the captured bombs

- Michael Brennan as Janni: One of Largo's thugs who is usually paired with Vargas.

- Anthony Dawson as Ernst Stavro Blofeld, voiced by Joseph Wiseman (both un-credited): The head of SPECTRE

- Bill Cummings as Quist: Another of Largo's inefficient thugs who, after failing to assassinate 007, is thrown into a shark pool under orders from his boss.

- André Maranne, best known for portraying Sergeant François Chevalier in the Pink Panther films, cameos as SPECTRE #10.

Production

Legal disputes

Further information: Rights controversy of ThunderballOriginally meant as the first James Bond film, Thunderball was the centre of legal disputes that began in 1961 and, as of 2008[update], continue. Former Ian Fleming collaborators Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham sued Fleming shortly after the 1961 publication of the Thunderball novel, claiming he based it upon the screenplay the trio had earlier written in a failed cinematic translation of James Bond.[2] The lawsuit was settled out of court; McClory retained certain screen rights to the novel's story, plot, and characters. By then, James Bond was a box office success, and series producers Broccoli and Saltzman feared a rival McClory film beyond their control; they agreed to McClory's producer's credit of a cinematic Thunderball, with them as executive producers.[11]

The sources for Thunderball are controversial among film aficionados. In 1961, Ian Fleming published his novel based upon a television screenplay that he, and others developed into the film screenplay; the efforts were unproductive, and Fleming expanded the script into his ninth James Bond novel. Consequently, one of his collaborators, Kevin McClory, sued him for plagiarism; they settled out of court in 1963.[12] The book The Battle for Bond, by Robert Sellers, details this as part of the Thunderball mythos.

Later, in 1964, Eon producers Broccoli and Saltzman agreed with McClory to cinematically adapt the novel; it was promoted as "Ian Fleming's Thunderball". Yet, along with the official credits to screenwriters Richard Maibaum and John Hopkins, the screenplay is also identified as based on an original screenplay by Jack Whittingham and as based on the original story by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham, and Ian Fleming.[11] To date, the novel has twice been adapted cinematically; the 1983, McClory-produced Never Say Never Again, features Sean Connery as James Bond, but is not an official Eon production.

Casting

Broccoli's original choice for the role of Domino Derval was Julie Christie following her performance in Billy Liar in 1963. Upon meeting her personally, however, he was disappointed and turned his attentions towards Raquel Welch after seeing her on the cover of the October 1964 issue of Life magazine. Welch, however, was hired by Richard Zanuck of 20th Century Fox to appear in the film Fantastic Voyage the same year instead. Faye Dunaway was also considered for the role and came close to signing for the part.[13] Saltzman and Broccoli auditioned an extensive list of relatively unknown European actresses and models including former Miss Italy Maria Grazia Buccella, Yvonne Monlaur of the Hammer horror films and Gloria Paul. Eventually former Miss France Claudine Auger was cast, and the script was rewritten to make her character French rather than Italian, although her voice was dubbed. Nevertheless, director Young would cast her once again in his next film, Triple Cross (1966). One of the actresses that tried for Domino, Luciana Paluzzi, later accepted the role as the redheaded femme fatale assassin Fiona Kelly who originally was intended by Maibaum to be Irish. The surname was changed to Volpe in coordination with Paluzzi's nationality.[13]

Filming

Guy Hamilton was invited to direct, but considered himself worn out and "creatively drained" after the production of Goldfinger.[1] Terence Young, director of the first two Bond films, returned to the series. Coincidentally, when Saltzman invited him to direct Dr. No, Young expressed interest in directing adaptations of Dr. No, From Russia With Love and Thunderball. Years later, Young said Thunderball was filmed "at the right time",[14] considering that if it was the first film in the series the short budget — Dr. No cost only $1 million — wouldn't have good results.[14]

Thunderball was the final James Bond film directed by Young.

Filming commenced on 16 February 1965, with principal photography of the opening scene in Paris. Filming then moved to the Château d'Anet, near Dreux, France for the fight in pre-credit sequence. Much of the film was shot in the Bahamas; Thunderball is widely known for its extensive underwater action scenes which are played out through much of the latter half of the film. Filming was shot at Pinewood Studios, Buckinghamshire, Silverstone racing circuit for the chase involving Count Lippe, Fiona Volpe and James Bond's Aston Martin DB5 before moving to Nassau, and Paradise Island in The Bahamas (where most of the footage was shot), and Miami.[15] Huntington Hartford gave permission to shoot footage on his Paradise Island and is thanked at the end of the movie.

On arriving in Nassau McClory searched for possible locations to shoot many of the key sequences of the film and used the home of a local millionaire couple, the Sullivans, for Largo's estate.[16] Part of the SPECTRE underwater assault was also shot on the coastal grounds of another millionaires' home on the island. The most difficult sequences to film were the underwater action scenes and the first to be shot underwater was at a depth of 50 feet to shoot the scene where SPECTRE divers remove the atomic bombs from the sunken Vulcan bomber. Peter Lamont had previously visited a Royal Air Force bomber station carrying a concealed camera which he used to get close-up shots of the secretive missiles and those appearing in the film were not actually present.[1] Most of the underwater scenes had to be done at lower tides due to the sharks in the Bahamian sea.[17]

Connery's life was in danger in the sequence with the sharks in Largo's pool and one which he had been in fear of when he read the script. He insisted that Ken Adam build a special Plexiglas partition inside the pool but, despite this, it was not a fixed structure and one of the sharks managed to pass through it. Connery had to abandon the pool immediately, seconds away from attack.[15] Another dangerous situation occurred when special effects coordinator John Stears brought in a supposed dead shark carcass to be towed around the pool. The shark, however, was not dead and revived at one point. Due to the dangers on the set, stuntman Bill Cummings demanded an extra fee £250 to double for Largo's sidekick Quist as he was dropped into the pool of sharks.[13]

The climactic underwater battle was shot at Clifton Pier and was choreographed by Hollywood expert Ricou Browning, who had worked on many films previously such as Creature From the Black Lagoon in 1954. He was responsible for the staging of the cave sequence and the battle scenes beneath the Disco Volante and called in his specialist team of divers who posed as those engaged in the onslaught. Voit provided much of the underwater gear in exchange for product placement and film tie-in merchandise. Lamar Boren, an underwater photographer, was brought in to shoot all of the sequences. United States Air Force Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Russhon, who had already helped alliance Eon productions with the local authorities in Turkey for From Russia With Love 1963 and at Fort Knox for Goldfinger 1964, stood by and was able to supply the experimental rocket fuel used to destroy the Disco Volante. Russhon, using his position, was also able to gain access to the United States Navy's Fulton surface-to-air recovery system, used to lift Bond and Domino from the water at the end of the film.[13] Filming ceased in May 1965 and the final scene shot was the physical fight on the bridge of the Disco Volante.[1]

While in Nassau, during the final shooting days, special effects supervisor John Stears was supplied experimental rocket fuel to use in exploding Largo's yacht, the Disco Volante. Ignoring the true power of the volatile liquid, Stears doused the entire yacht with it, took cover, and then detonated the boat. The resultant massive explosion shattered windows along Bay Street in Nassau roughly 30 miles away.[1] Stears went on to win an Academy Award for his work on Thunderball.

As the filming neared its conclusion, Connery had become increasingly agitated with press intrusion and was distracted with difficulties in his marriage of 32 months to actress Diane Cilento. Connery refused to speak to journalists and photographers who followed him in Nassau stating his frustration with the harassment that came with the role; "I find that fame tends to turn one from an actor and a human being into a piece of merchandise, a public institution. Well, I don't intend to undergo that metamorphosis."[18] In the end he only gave a single interview to Playboy as filming was wrapped up, and even turned down a substantial fee to appear in a promotional TV special made by Wolper Productions for NBC The Incredible World of James Bond.[13] According to editor Peter R. Hunt, Thunderball's release was delayed for three months, from September until December 1965, after he met Arnold Picker of United Artists, and convinced him it would be impossible to edit the film to a high enough standard without the extra time.[19]

Effects

Agent 007's escape flight with the Bell Rocket Belt jet belt in Thunderball's pre-title teaser.

Agent 007's escape flight with the Bell Rocket Belt jet belt in Thunderball's pre-title teaser. Main articles: List of James Bond vehicles and List of James Bond gadgets

Main articles: List of James Bond vehicles and List of James Bond gadgetsThanks to Special Effects genius John Stears Thunderball's pre-title teaser, the Aston Martin DB5 (introduced in Goldfinger), reappears armed with rear-firing water cannon, seeming noticeably weathered – just dust and dirt raised, moments earlier, by Bond's landing with the Bell Rocket Belt (developed by Bell Aircraft Corporation). The rocket belt Bond uses to escape the château actually worked, and was used many times, before and after, for entertainment, most notably at Super Bowl I and at scheduled performances at the 1964-1965 New York World's Fair.[20]

Bond receives a spear gun-armed underwater jet pack scuba (allowing the frogman to manoeuvre faster than other frogmen). Designed by Jordan Klein, green dye was meant to be used by Bond as a smoke screen to escape pursuers.[21] Instead Ricou Browning, the film's underwater director, used it to make Bond's arrival more dramatic.[22]

The sky hook, used to rescue Bond at the end of the film, was a rescue system used by the United States military at the time. At Thunderball's release, there was confusion as to whether a rebreather such as the one that appears in the film existed; most Bond gadgets, while implausible, often are based upon real technology. In the real world, a rebreather could not be so small, as it has no room for the breathing bag, while the alternative open-circuit scuba releases exhalation bubbles, which the film device does not. It was made with two CO2 bottles glued together and painted, with a small mouthpiece attached.[22] For this reason, when the Royal Corps of Engineers asked Peter Lamont how long a man could use the device underwater, the answer was "As long as you can hold your breath."[23]

Maurice Binder was hired to design the title sequence, and was involved in a dispute with Eon Production to have his name credited in the film. As Thunderball was the first James Bond film shot in Panavision, Binder had to reshoot the iconic gun barrel scene which permitted him to not only incorporate pinhole photographic techniques to shoot inside a genuine gun barrel, but also made Connery appearing in the sequence for the first time a reality, as stunt man Bob Simmons had doubled for him in the three previous films. Binder gained access to the tank at Pinewood which he used to film the silhouetted title girls who appeared naked in the opening sequence, which was the first time actual nudity (although concealed) had ever been seen in a Bond film.[13]

Parts of the climactic sequence on board the Disco Volante (Italian: Flying Saucer) were sped up to make the boat look as if it was going faster than it was. Additionally, some shots were repeated. During the hand-to-hand combat, one shot of the boat (sped up) is of Bond and Domino about to jump overboard, but cuts back to the fight. This same shot appears again at normal speed when Bond and Domino jump overboard.

Music

See also: Thunderball (soundtrack)The title theme was written by John Barry and Leslie Bricusse. It was the third James Bond score composed by Barry, after From Russia With Love and Goldfinger. It was originally entitled "Mr. Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang", taken from an Italian journalist who in 1962 dubbed agent 007 as Mr. Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang. The song was originally recorded by Shirley Bassey, but was later rerecorded by Dionne Warwick, whose version was not released until the 1990s. The song was removed from the title credits after producers Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman were worried that a theme song to a James Bond film would not work well if the song did not have the title of the film in its lyrics.[1] Barry then teamed up with lyricist Don Black and wrote "Thunderball", which was sung by Tom Jones who, according to Bond production legend, fainted in the recording booth when singing the song's final note. Jones said of it, "I closed my eyes and I held the note for so long when I opened my eyes the room was spinning."[24] The song, Maurice Binder's titles, and the lengthy holding of the final note were parodied by Weird Al Yankovic's title sequence for Spy Hard with instrumental backing by Jimmie Haskell.

Country musician Johnny Cash also submitted a song to Eon productions titled "Thunderball", but it went unused.[25]

Box office performance

The film premiered on 9 December 1965 in Tokyo and opened on 29 December 1965 in the UK. It was a major success at the box office with record-breaking earnings, rivalling the newly released The Sound of Music, and was a greater success than the epic Battle of the Bulge. Variety reported that Thunderball was the #1 money maker of 1966 by a large margin, with a net profit of $26,500,000.[26] The second highest money maker of 1966 was Doctor Zhivago at $15,000,000; in third place was Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? at $10,300,000.[26]

A total of 58.1 million admissions were recorded in the USA totalling a gross of $63.6 million (a record), and the film earned more in the first week than the previous three films combined. France and Italy also reported record takings, scooping $95,000 and $79,000 respectively within the first three days of screening. The film eventually earned a global total of $141.2 million which in 2002, was calculated to be the equivalent of roughly $950 million, taking inflation into account.[27]

Reception

In 1965, the film received generally positive reviews. Dilys Powell of The Sunday Times remarked after seeing the film that "The cinema was a duller place before Bond."[28] In Kinematograph Weekly, she emphasised her enjoyment of the film, particularly the combination of humour, Bond girls, and the effectiveness of the Caribbean location on the cinema screen. However she criticised part of the plot in that the explanation of SPECTRE's ransom plan took too long. [29] David Robinson of The Financial Times criticised the appearance of Connery and his effectiveness to play Bond in the film remarking: "It's not just that Sean Connery looks a lot more haggard and less heroic than he did two or three years ago; but there is much less effort to establish him as connoisseur playboy. Apart from the off-handed order for Beluga, there is little of that comic display of bon viveur-manship that was one of the charms of Connery's almost-a-gentleman 007."[30]

According to Danny Peary, Thunderball “takes forever to get started and has too many long underwater sequences during which it’s impossible to tell what’s going on. Nevertheless, it’s an enjoyable entry in the Bond series. Sean Connery is particularly appealing as Bond – I think he projects more confidence than in other films in the series. Film has no great scene, but it’s entertaining as long as the actors stay above water.”[31]

Critics such as James Berardinelli praised Connery's performance, the femme fatale character of Fiona Volpe and the underwater action sequences, remarking that they were well choreographed and clearly shot. He criticised the length of the scenes, however, and believed they were too long and in need of editing, particularly during the film's climax.[32] At Rotten Tomatoes, the film received a 88% "fresh" rating.[33]

Thunderball won an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects awarded to John Stears in 1966.[4] Ken Adam the production director was also nominated for a Best Production Design BAFTA award.[5] The film won the Golden Screen award for Best Film in Germany and won the Golden Laurel Action Drama award at the 1966 Laurel Awards. The film was also nominated for an Edgar Best Foreign Film award at the Edgar Allan Poe Awards.[34]

References

- ^ a b c d e f The Making of Thunderball: Thunderball Ultimate Edition, Region 2, Disc 2 (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment. 1995.

- ^ a b "McClory, Sony and Bond: A History Lesson". Universal Exports.net. http://www.universalexports.net/00Sony.shtml. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ "Thunderball". The Numbers. Nash Information Service. http://the-numbers.com/movies/1965/0THBA.php. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ^ a b "The 1966 Oscar Awards". RopeofSilicon. http://www.ropeofsilicon.com/award_show/oscars/1966. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ a b "BAFTA Awards 1965". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. http://www.bafta.org/awards/film/nominations/?year=1965. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ The name is often mis-spelled. Officially it is spelled Bouvar on Thunderball Ultimate Edition DVD Region 2. See Disc One, English subtitles for the film, and Disc Two under "007 Mission Control / Villains / Jacques Bouvar"

- ^ (2006) Album notes for Thunderball Ultimate Edition DVD.

- ^ George A. Rooker. "Film Industry Tricks OR How to fool most of the people most of the time!". Official Nikki van der Zyl website. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070927225114/http://www.nikkivanderzyl.co.uk/bond/. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ Cork, John. Commentary 1: Thunderball Ultimate Edition, Region 2 (DVD).

- ^ Peters, Molly. Commentary 1: Thunderball Ultimate Edition, Region 2 (DVD).

- ^ a b Cork, John. "Inside "Thunderball"". Mr. Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. Archived from the original on November 20, 2005. http://web.archive.org/web/20051120153537/http://www.ianfleming.org/mkkbb/magazine/inside_tb3.shtml. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ "The Battle for Bond: Sony vs. MGM". 1997-02-20. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070927203914/http://www.ianfleming.org/007news/articles/bondvsony.shtml. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ a b c d e f "Production notes for Thunderball". MI6.co.uk. http://www.mi6.co.uk/sections/movies/tb_production.php3?t=tb&s=tb. Retrieved 2007-12-30.

- ^ a b Young, Terence (Audio commentary). Commentary 1: Thunderball Ultimate Edition DVD Region 4 (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment.

- ^ a b The Thunderball Phenomenon (DVD). Thunderball Ultimate Edition DVD, Region 2,Disc 2: MGM/UA Home Entertainment. 1995.

- ^ 007 Mission Control: Exotic Locations (DVD). Thunderball Ultimate Edition DVD, Region 2,Disc 2: MGM/UA Home Entertainment. 2006.

- ^ (Audio commentary) Commentary 1: Thunderball Ultimate Edition, Region 2 (DVD).

- ^ "Interview with Sean Connery". Playboy (HMH Publishing) (November 1965). ISSN 0032-1478. http://www.obsessional.co.uk/playboy.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-15.

- ^ Hunt, Peter R. (Audio commentary). Commentary 2: Thunderball Ultimate Edition DVD Region 2 (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment.

- ^ Malow, Brian. "Where the hell is my Jetpack?". Butseriously.com. http://www.butseriously.com/jetpack.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ John Cork (Audio commentary). Commentary 2: Thunderball Ultimate Edition, Region 2 (DVD).

- ^ a b Browning, Ricou (Audio commentary). Commentary 1: Thunderball Ultimate Edition, Region 2 (DVD).

- ^ Lamont, Peter (1995). The Thunderball Phenomenon: Thunderball Ultimate Edition, Region 2, Disc 2 (DVD). MGM/UA Home Entertainment.

- ^ "Tom Jones's comments on the Thunderball song". Interview with Singer Tom Jones. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1544163. Retrieved 2005-09-10.

- ^ "Bitter Cinema piece on Johnny Cash's Thunderball". http://www.bittercinema.com/2004/03/johnny-cashs-thunderball.html. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Cobbett (1980). Film Facts. New York: Facts on File, Inc.. p. 23. ISBN 0-87196-313-2. When a film is released late in a calendar year (October to December), its income is reported in the following year's compendium, unless the film made a particularly fast impact. Figures are domestic earnings (United States and Canada) as reported each year in Variety (p. 17).

- ^ Copyright 1998-2010. "Premiere notes for Thunderball —". Mi6.co.uk. http://www.mi6.co.uk/sections/articles/tb_premiere.php3?t=tb&s=tb. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (1965). "Thunderball film review". The Sunday Times.

- ^ Powell, Dilys (1965-12-20). "Thunderball film review". Kinematograph Weekly.

- ^ David, Robinson. "Thunderball film review". The Financial Times.

- ^ Peary, Danny (1986). Guide for the Film Fanatic (Simon & Schuster) p.435

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "Thunderball". ReelViews. http://www.reelviews.net/movies/t/thunderball.html. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ "Thunderball". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/thunderball/. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ^ "Awards for Thunderball(1965)". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0059800/awards. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

Bibliography

- Thompson, Scott A. (August 2000). Final Cut – The Post-War B-17 Flying Fortress: The Survivors, Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Missoula, Montana, Revised Edition, First Printing. ISBN 1-57510-077-0, pages 138-143.

Further reading

- Differences between James Bond novels and films

- Casino Royale history for further information on the James Bond legal disputes between Sony and MGM.

- Chapman, James (1999). Licence To Thrill: A Cultural History Of The James Bond Films. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-86064-387-6.

External links

- Thunderball at the Internet Movie Database

- Thunderball at AllRovi

- Thunderball at Rotten Tomatoes

- Thunderball at Box Office Mojo

- MGM's official site for Thunderball

- Official James Bond website

- Universal Export's entry on Thunderball

- Thunderball Overview on James Bond Wiki

- Thunderball obsessional; a website devoted to all things, Thunderball

Preceded by

GoldfingerJames Bond Films

1965Succeeded by

You Only Live TwiceJames Bond films List of James Bond filmsEon Productions - Dr. No (1962)

- From Russia with Love (1963)

- Goldfinger (1964)

- Thunderball (1965)

- You Only Live Twice (1967)

- Diamonds Are Forever (1971)

- Live and Let Die (1973)

- The Man with the Golden Gun (1974)

- The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

- Moonraker (1979)

- For Your Eyes Only (1981)

- Octopussy (1983)

- A View to a Kill (1985)

- The Living Daylights (1987)

- Licence to Kill (1989)

- GoldenEye (1995)

- Tomorrow Never Dies (1997)

- The World Is Not Enough (1999)

- Die Another Day (2002)

- Casino Royale (2006)

- Quantum of Solace (2008)

- Skyfall (2012)

Non-Eon films - Casino Royale (1967)

- Never Say Never Again (1983)

The films of Terence Young 1940s 1950s They Were Not Divided • Valley of Eagles • The Tall Headlines • The Red Beret • That Lady • Storm Over the Nile (with Zoltan Korda) • Safari • Zarak • Action of the Tiger • No Time to Die • Serious Charge1960s Black Tights • Too Hot to Handle • Duel of Champions • Dr. No • From Russia with Love • The Amorous Adventures of Moll Flanders • The Dirty Game (with Christian-Jacque, Werner Klingler, and Carlo Lizzani) • Thunderball • The Poppy Is Also a Flower • Triple Cross • The Rover • Wait Until Dark • Mayerling • The Christmas Tree1970s Cold Sweat • Red Sun • The Valachi Papers • The Amazons • The Klansman • Foxbat (with Po-Chih Leong) • Bloodline1980s Screen-

playsOn the Night of the Fire (with Brian Desmond Hurst and Patrick Kirwan) (1939) • Dangerous Moonlight (1941) • Secret Mission (with Basil Bartlett and Anatole de Grunwald) (1942) • On Approval (with Clive Brook) (1944) • Hungry Hill (with Daphne Du Maurier) (1947) • The Bad Lord Byron (with Paul Holt, Laurence Kitchin, Peter Quennell and Anthony Thorne) (1949) • Atout coeur à Tokyo pour OSS 117 (with Pierre Foucaud) (1966)Categories:- 1965 films

- British films

- English-language films

- Films shot anamorphically

- Films set in Miami, Florida

- James Bond films

- Pinewood Studios films

- Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award

- Films shot in the Bahamas

- Films shot in Florida

- Films shot in France

- Thunderball (film)

- Films directed by Terence Young

- Underwater action films

- Aviation films

- Sequel films

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- United Artists films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.