- Proposals for new Australian states

-

A number of proposals for the creation of additional states in Australia have been made in the past century. However, to date, none have been added to the Commonwealth since Federation in 1901. Many proposals have suggested an Aboriginal state which would resemble the Inuit territory of Nunavut in Canada, whilst others have suggested incorporating New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Fiji, or New Caledonia as new states.[1]

Contents

Formation of new states

Chapter VI of the Constitution of Australia allows for the establishment or admission of new states to the Federation. It may also increase, diminish, or otherwise alter the limits of a state, form new states by separating territory from an existing state, or join two states or parts of states, but in each case it must have the approval of the parliaments of the states in question.[2]

New colony proposals

There were proposals for new colonies in the 19th century that did not come about. North Australia was briefly a colony between February and December 1846. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society published Considerations on the Political Geography and Geographical Nomenclature of Australia in 1838, in which the following divisions were proposed:

- Dampieria in northwestern Australia.

- Queen Victoria in southwestern Australia (not to be confused with the modern Victoria).

- Tasmania in Western Australia (not to be confused with the modern Tasmania).

- Nuytsland near the Nullarbor Plain.

- Carpentaria south of the Gulf of Carpentaria.

- Flindersland in south central Australia.

- Torresia in northern Queensland.

- Cooksland centred around Brisbane.

- Guelphia in southeastern Australia.

- Van Diemen's Land in modern day Tasmania.

These proposed states were geometric divisions of the continent, and did not take into account soil fertility, aridity or population. This meant that central and western Australia were divided into several states, despite their low populations both then and now.

There was also a proposal in 1857 [3] for the "Seven United Provinces of Eastern Australia" with separate provinces of Flinders Land, Leichardt's Land (taken from the name of Ludwig Leichhardt) and Cook's Land in modern day Queensland (also named from James Cook).

Current Internal proposals

From Territories

Australian Capital Territory

The ACT has a small number of vocal statehood supporters,[who?] who believe the ACT, with a population only slightly less than that of Tasmania, is under-represented in the Australian Parliament. This movement may be likened to supporters of statehood for the District of Columbia in the United States, though it is much smaller and no prominent political figures have given it their support. Furthermore, the wording of s.125 of the Australian Constitution suggests that the ACT must remain a territory and cannot become a state.[4]

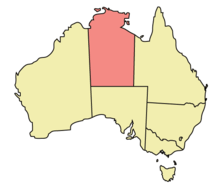

Northern Territory

The Northern Territory is the most commonly mentioned potential seventh state. In a 1998 referendum, the voters of the NT rejected a statehood proposal that would have given the Territory three Senators, rather than the 12 Senators held by the other states, although the name "Northern Territory" would have been retained. This ABC Lateline interview gives much insight into both sides of the debate in 1998. With statehood rejected, it is likely that the Northern Territory will remain a territory for the near future, though former Chief Minister Clare Martin and the majority of Territorians[citation needed] are said to be in favour of statehood. The main argument against statehood has been the NT's relatively low population.[citation needed]

An alternative name for the new state would be North Australia, which would be shared by two historic regions.[citation needed]

From Parts of other states

North Queensland

The people of northern North Queensland, sometimes called "Far North Queensland" [5] or "Capricornia", have long held views and self-identification distinct from that of the southern parts of the state.[citation needed] Proposals for the political separation of North Queensland, comprising mainly the Cape York Peninsula, have been forwarded from time to time, with mixed results. Arguably, efforts for statehood in North Queensland would be hampered by the region's small population, although if Central Queensland was included, the state could potentially have a population higher than South Australia.

See also: North Queensland Party, Central Queensland Territorial Separation League, and State of North QueenslandRiverina

Riverina is also a proposed state,[6] in the River Murray region, on the border between New South Wales and Victoria. The Division of Riverina is currently a smaller area than traditional Riverina, which would include the Division of Farrer. Along with the ACT, it is one of the few landlocked proposed states.

Aboriginal state

There are also supporters of an Aboriginal state, along the lines of the recently created Nunavut in Canada.[7] Agence France Presse (21/8/98) claims Australia blocked a United Nations resolution calling for the self-determination of peoples, because it would have bolstered support for an Aboriginal state within Australia.[8] Amongst those supporting such a state are the Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation.[9]

Past Internal proposals

Auralia

Approximate location of New England within New South Wales; red a narrow definition, yellow a broader definition

Proposed in the late 19th century/early 20th, the state of Auralia (meaning "land of gold") would have comprised the Goldfields, the western portion of the Nullarbor Plain and the port town of Esperance. Its capital would have been Kalgoorlie.[10] However, the population in Goldfields-Esperance is currently lower than that of the Northern Territory, and there is not much evidence of support, although the idea of a state around Kalgoorlie has been revived.[6]

Central Australia

In 1927 the Northern Territory administrated devolved authority for the governing of the southern portion of the territory known as Central Australia, with power vested in an administrator resident in Alice Springs. The arrangement was discontinued in 1931.

Illawarra Province

Also known as the Illawarra Territory, this proposed new state would consist of the Illawarra region centred around Wollongong on the New South Wales south coast. Originally this idea arose after disagreements between local landowners and migrants from Sydney in the mid-19th century. However the idea has continued in various incarnations ever since with most movements proposing the state's capital be situated in "Illawarra City", or the amalgamation of the Shellharbour and Kiama local government areas.

New England

Main article: New England New State MovementThe New England region of New South Wales has had a devoted statehood movement since the 1930s. In the 1960s this movement was particularly active. The movement has historically gained strength when a Labor government, generally dominated by urban interests, is in power in Sydney.

Some supporters also propose a "River-Eden" state in the south of NSW.[11]

North Coast

This proposed state takes in the northern part of New South Wales from Taree to the Queensland Border,[12] mainly in the north east, and excluding most of north west NSW.

South Coast

There was a small movement in the 1940s to create a new state in south-east New South Wales and north-east Victoria. The proposed state would have reached from Batemans Bay on the coast to Kiandra in the Snowy Mountains, and as far south as Sale in Victoria. The proposed state capital was Bega. Despite calls from local advocacy groups for a Royal Commission into the idea, it was met with little success.[13]

Princeland

Main article: PrincelandThis proposed colony resulted from a movement in the 1860s to create a new colony that incorporated the isolated western Victoria and south-eastern South Australia regions centred around Mount Gambier and Portland. A petition was presented to Queen Victoria, but was rejected.[14]

External proposals

New Zealand

There have been several proposals for New Zealand to become the seventh state of Australia. One of the proposals suggest that New Zealand's North Island and South Island could become separate states in the Commonwealth, which would provide New Zealand interests with a greater say.[15] New Zealand was one of the colonies asked to join in the creation of the Commonwealth of Australia. As ties have grown closer, people have made proposals for a customs union, currency union and even a joint defence force. New Zealand and Australia enjoy close economic and political relations, mainly by way of the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement, Closer Economic Relations (CER) free trade agreement signed in 1983 and the Closer Defence Relations agreement signed in 1990. In 1989, former Prime Minister of New Zealand Sir Geoffrey Palmer said that New Zealand had "...gained most of the advantages of being a state of Australia without becoming one". The two countries, along with the USA, are in ANZUS, but New Zealand's opposition to nuclear weapons has weakened this treaty.

History

In 1788 Arthur Phillip assumed the position of Governor of New South Wales, claiming New Zealand as part of New South Wales. In 1835 a group of Māori chiefs signed the Declaration of Independence, which established New Zealand as a sovereign nation. A few years later the Treaty of Waitangi re-established British control of New Zealand. The Federal Council of Australasia was formed with members representing New Zealand, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia and Fiji. Although it held no official power it was a step into the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia. In 1890 there was an informal meeting of members from the Australasian colonies, this was followed by the first National Australasian convention a year later. The New Zealand representatives stated it would be unlikely to join a federation with Australia at its foundation but it would be interested in doing so at a later date. New Zealand's position was taken into account when the Constitution of Australia was written up. The only reason New Zealand did not join was fears of racist laws towards the Māori because of Australia's treatment of the Australian Aboriginals. Australia in an attempt to sway New Zealand to join gave Māori the right to vote in 1902, while Australian Aboriginals did not gain the right to vote until 1962. New Zealand and Australian soldiers fought together in 1915 under the name ANZAC.

Australian academic Bob Catley wrote a book titled Waltzing with Matilda: should New Zealand join Australia?, a book arguing why New Zealand should become one with Australia. In December 2006, an Australian Federal Parliamentary Committee recommended that Australia and New Zealand pursue a full union, or at least adopt a common ANZ currency and more common markets. The Committee found that "while Australia and New Zealand are of course two sovereign nations, it seems ... that the strong ties between the two countries - the economic, cultural, migration, defence, governmental and people-to-people linkages - suggest that an even closer relationship, including the possibility of union, is both desirable and realistic." This was despite the Australian Treasurer Peter Costello and New Zealand Minister of Finance Michael Cullen saying that a common currency was "not on the agenda."[16] A recent UMR research poll asked 1000 people in Australia and New Zealand a series of questions relating to New Zealand becoming the seventh state of Australia. One quarter of the people thought it was something to look into. Over 40% thought the idea was worth debating. More Australians than New Zealanders would support such a move.[17]

Reasons for

There are many reasons why people have called for New Zealand to become the seventh state of Australia. Some of the reasons depend which side of the Tasman the person is on. A prominent reason appears to be the two countries are very alike, from their similar flags to their culture values. According to the UMR poll results most people believe the New Zealand economy and the ease of travel between countries would be better if New Zealand joined Australia.[17] A leading factor for the proposal of New Zealand as a state of Australia is the major economic benefits it would bring. But at present, free trade and open borders appear to be the maximum extent of public acceptance of the proposal. New Zealand's health system would improve.[18] There are a lot of family connections between the two nations, with nearly half a million New Zealanders currently living in Australia. Peter Slipper, a Member of Australia's Parliament, once said "It's about how can we improve the quality of living for people on both sides of the Tasman." when referring to the proposal.[19]

Reasons against

The modern reasons for New Zealand not becoming the seventh state differ from the original belief that Māori may be mistreated under Australian law. The main reason for New Zealanders refusing the proposal is not wanting to be labelled an 'Australian'.[19] Each country has its own currency which would mean a common currency would have to be created before New Zealand becomes a state. Also there have been fears of New Zealand losing its nuclear-free status, although these fears are unfounded, Australia was even one of the nations to sign the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.[20] New Zealand has stronger administrative and political recognition of the ancestral rights of its indigenous Maori population due to the Treaty of Waitangi, whereas Australia does not. However, the Treaty of Waitangi would continue in operation in any union, just as it has through New Zealand's development from colony to independent nation. New Zealand also has a Bill of Rights, albeit not entrenched, whereas Australia does not, at least as a federal level. There are also disparities that would lead to conflict within social movements on either side of the Tasman. Same-sex marriage in New Zealand is not subject to a prescriptive federal statutory ban, unlike same-sex marriage in Australia, as one example. Some New Zealanders feel they have established a national identity, one which they feel they may lose if they became part of Australia.[17] Others argue New Zealand is too far away from the mainland of Australia, although Julius Vogel once stated, Otago was three times as far from the Auckland than it was from Victoria or Tasmania in terms of shipping days.[21]

Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea is the physically closest of any country to geographically remote Australia, with some of the Torres Strait Islands just off the main island of the country. In 1953, the editor of the conservative Quadrant magazine, Professor James McAuley, wrote that the territory would be "a coconut republic which would do little good for itself", and advocated its "perpetual union" with Australia, with equal citizenship rights.",[22] but this was rejected by the Australian government [23] which instead granted the territory self-government, and full independence in 1975.

See also: Territory of Papua and New GuineaEast Timor

During the process of Portuguese decolonisation in East Timor in 1974, a political party was formed called ADITLA Associação Democrática para a Integração de Timor Leste na Austrália or Democratic Association for the Integration of East Timor into Australia, by local businessman Henrique Pereira. It found some support from the ethnic Chinese community, fearful of independence or integration with Indonesia, but was disbanded when the Australian government rejected the idea in 1975.[24]

Proponents of new states

Some members of the National Party (former Country Party) have been especially supportive of new states, since they believe it would decentralise Australia and benefit rural areas more.

In addition to the above, Bryan Pape, National Party official and senior lecturer in law at the University of New England, has suggested further subdivision of Victoria and the following states, resulting in possibly as many as twenty Australian states:[6] A suggested reorganisation of Australia's states could include:

- Central Australia

- Northern Australia

- Queensland

- Carpenteria

- Cape York/North Queensland

- South Australia

- Whyalla

- Eyre Peninsula

- Victoria

- Gippsland

- Ballarat-Bendigo/Goldfields

- Wimmera-The Mallee

- Western Australia

See also

- Australian regional rivalries

- Proposed provinces and territories of Canada

- Secessionism in Western Australia

- 51st state

- List of regions in Australia

- Australia – New Zealand relations

- Australia – Papua New Guinea relations

References

- ^ Blogger, Guest (2008-06-16). "New Caledonia: What now after twenty years of peace?". Lowyinterpreter.org. http://www.lowyinterpreter.org/post/2008/06/16/new-caledonia.aspx. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act, Chapter VI Commonwealth of Australia, 2003. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ^ "Digital Collections - Maps - Map of the proposed seven united provinces of eastern Australia [cartographic material]". Nla.gov.au. http://nla.gov.au/nla.map-rm3518. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ "58490 text" (PDF). http://www.comlaw.gov.au/comlaw/comlaw.nsf/0/19541afd497bc2e4ca256f990081e2cf/$FILE/Constitution.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ Population Growth - The Far North Queensland Region 2005

- ^ a b c "The man who's creating a United States of Australia". smh.com.au. 2003-05-11. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/05/10/1052280480600.html. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ http://melbourne.indymedia.org/news/2004/01/61201.php

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "The Sydney Line". The Sydney Line. http://www.sydneyline.com/Breakup%20of%20Australia.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/federation/journey/episode3/nation.htm

- ^ "Altered states - National". www.smh.com.au. 2005-01-25. http://www.smh.com.au/news/National/Altered-states/2005/01/24/1106415528397.html. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ http://www.newstates.com.au/voting.html

- ^ "NLA Australian Newspapers - article display". Ndpbeta.nla.gov.au. http://ndpbeta.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/2764438. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ "Lateline - 22/09/2003: A Suitable Consort . Australian Broadcasting Corp". Abc.net.au. 2003-09-22. http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/content/2003/hc43.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ "unitedstatesofaustralia.com". unitedstatesofaustralia.com. http://www.unitedstatesofaustralia.com/. Retrieved 2010-04-29.

- ^ Dick, Tim, "Push for union with New Zealand", Sydney Morning Herald, 5 December 2006. Accessed 29 February 2007.]

- ^ a b c "Full UMR research poll results on Aust-NZ union". Television New Zealand. 14 March 2010. http://tvnz.co.nz/national-news/full-umr-research-poll-results-aust-nz-union-3414686. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ http://www.joinaustraliamovement.co.nz/

- ^ a b [2]

- ^ http://www.fas.org/nuke/control/spnfz/text/spnfz.htm

- ^ http://www.dreamlike.info/nzl/southisland.htm

- ^ McAuley, James "Australia's Future in New Guinea", Pacific Affairs, Vol. 26, No. 1 (Mar., 1953), pp. 59-69. [Accessed 25 May 2008. cited by Kiernan, Ben in "Cover-Up and Denial of Genocide: Australia, the USA, East Timor and the Aborigines" Critical Asian Studies, Yale University, p.169

- ^ "London Constitutional Conference" in Fiji, Brij V Lal, University of London, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, 2006. [Accessed 26 May 2008.]

- ^ "The Chinese and Aditla" p. 58 in in Timor: A Nation Reborn, Nicol, Bill, Equinox Publishing, 2002. [Accessed 26 May 2008.]

External links

- 'Altered States', Sydney Morning Herald 25 January 2005

- New States for Australia

- New states Introduction - Ian Johnston's new Australian States webpage

- The man who's creating a United States of Australia

- Proposed North Queensland flag and brief history

- North Queensland secession discussion forum

- Why New Zealand did not become an Australian State

Constitution of Australia Chapters I: The Parliament · II: The Executive · III: Courts · IV: Finance and trade · V: The States · VI: New States · VII: Miscellaneous · VIII: Amendments

Sections 1 · 2 · 3 · 4 · 5 · 6 · 7 · 8 · 9 · 10 · 11 · 12 · 13 · 14 · 15 · 16 · 17 · 18 · 19 · 20 · 21 · 22 · 23 · 24 · 25 · 26 · 27 · 28 · 29 · 30 · 31 · 32 · 33 · 34 · 35 · 36 · 37 · 38 · 39 · 40 · 41 · 42 · 43 · 44 · 45 · 46 · 47 · 48 · 49 · 50 · 51 · 52 · 53 · 54 · 55 · 56 · 57 · 58 · 59 · 60 · 61 · 62 · 63 · 64 · 65 · 66 · 67 · 68 · 69 · 70 · 71 · 72 · 73 · 74 · 75 · 76 · 77 · 78 · 79 · 80 · 81 · 82 · 83 · 84 · 85 · 86 · 87 · 88 · 89 · 90 · 91 · 92 · 93 · 94 · 95 · 96 · 97 · 98 · 99 · 100 · 101 · 102 · 103 · 104 · 105 · 106 · 107 · 108 · 109 · 110 · 111 · 112 · 113 · 114 · 115 · 116 · 117 · 118 · 119 · 120 · 121 · 122 · 123 · 124 · 125 · 126 · 127 · 128

Powers under Section 51interstate trade and commerce · taxation · communication · defence · quarantine · fisheries · currency · banking · insurance · copyrights, patents and trademarks · naturalization and aliens · corporations · marriage · divorce · pensions · social security · race · immigration · external affairs · acquisition of property · conciliation and arbitration · transition · referral · incident

Amendments Category:Amendments to the Constitution of Australia · Referendums

Other documents Institutions Theories and

doctrinesResponsible government · Separation of powers · Federalism · Reserved State powers · Implied immunity of instrumentalities

Other topics Australian constitutional law · Constitutional custom · Reserve power · Constitutional history of Australia · 1975 Australian constitutional crisis · Proposals for new Australian states · Australian republicanism

Global governance and identity Proposals Theories Cosmopolitanism · Democratic globalization · Global governance · Transnational governance · Global citizenship · Globalism · Internationalism · World citizen · World currency · world taxation systemOrganisations Categories:- Government of Australia

- Proposed states and territories of Australia

- Foreign relations of New Zealand

- Foreign relations of Papua New Guinea

- Foreign relations of Fiji

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.