- Ivan the Terrible

-

For other uses, see Ivan the Terrible (disambiguation).

Ivan IV the Terrible Ivan IV the Terrible Tsar of All Russia Reign 3 December 1533 – 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584 Coronation 16 January 1547 Predecessor Vasili III (as Grand Prince of Moscow) Successor Feodor I Consort Anastasia Romanovna

Maria Temryukovna

Marfa Sobakina

Anna Koltovskaya

Anna Vasilchikova

Vasilisa Melentyeva

Maria Dolgorukaya

Maria NagayaIssue Tsarevich Ivan Ivanovich

Feodor I of Russia

Tsarevich Dmitri IvanovichFull name Ivan Vasilyevich Dynasty Rurik Father Vasili III Mother Elena Glinskaya Born 25 August 1530

Kolomenskoye, near MoscowDied 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584 (aged 53)

MoscowBurial Kelmisvi Chapel, Moscow Religion Russian Orthodox Ivan IV Vasilyevich (Russian:

Ива́н Четвёртый, Васи́льевич (help·info), Ivan Chetvyorty, Vasilyevich; 25 August 1530 – 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584),[1] known in English as Ivan the Terrible (Russian:

Ива́н Четвёртый, Васи́льевич (help·info), Ivan Chetvyorty, Vasilyevich; 25 August 1530 – 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584),[1] known in English as Ivan the Terrible (Russian:  Ива́н Гро́зный (help·info), Ivan Grozny; lit. Fearsome), was Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 until his death. His long reign saw the conquest of the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia, transforming Russia into a multiethnic and multiconfessional state spanning almost one billion acres, approximately 4,046,856 km2 (1,562,500 sq mi).[2] Ivan managed countless changes in the progression from a medieval state to an empire and emerging regional power, and became the first ruler to be crowned as Tsar of All Russia.

Ива́н Гро́зный (help·info), Ivan Grozny; lit. Fearsome), was Grand Prince of Moscow from 1533 until his death. His long reign saw the conquest of the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia, transforming Russia into a multiethnic and multiconfessional state spanning almost one billion acres, approximately 4,046,856 km2 (1,562,500 sq mi).[2] Ivan managed countless changes in the progression from a medieval state to an empire and emerging regional power, and became the first ruler to be crowned as Tsar of All Russia.Historic sources present disparate accounts of Ivan's complex personality: he was described as intelligent and devout, yet given to rages and prone to episodic outbreaks of mental illness. One notable outburst may have resulted in the death of his groomed and chosen heir Ivan Ivanovich, which led to the passing of the Tsardom to the younger son: the weak and possibly intellectually disabled[3] Feodor I of Russia. His contemporaries called him "Ivan Groznyi" the name, which, although usually translated as "Terrible", actually means something closer to "Redoubtable" or "Severe" and carries connotations of might, power and strictness rather than horror or cruelty.[4][5][6]

Contents

Early reign

Ivan was the son of Vasili III and his second wife, Elena Glinskaya. When Ivan was just three years old his father died from a boil and inflammation on his leg which developed into blood poisoning. Ivan was proclaimed the Grand Prince of Moscow at his father's request. At first, his mother Elena Glinskaya acted as a regent, but she died of what many believe to be assassination by poison[7] when Ivan was only eight years old. According to his own letters, Ivan and his younger brother Yuri often felt neglected and offended by the mighty boyars from the Shuisky and Belsky families.

Ivan was crowned tsar with Monomakh's Cap at the Cathedral of the Dormition at age 16 on 16 January 1547. Despite calamities triggered by the Great Fire of 1547, the early part of his reign was one of peaceful reforms and modernization. Ivan revised the law code (known as the sudebnik), created a standing army (the streltsy),[8] established the Zemsky Sobor or assembly of the land, a public, consensus-building assembly, the council of the nobles (known as the Chosen Council), and confirmed the position of the Church with the Council of the Hundred Chapters, which unified the rituals and ecclesiastical regulations of the entire country. He introduced local self-government to rural regions, mainly in the northeast of Russia, populated by the state peasantry. During his reign the first printing press was introduced to Russia (although the first Russian printers Ivan Fedorov and Pyotr Mstislavets had to flee from Moscow to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania).

In 1547 Hans Schlitte, the agent of Ivan, recruited craftsmen in Germany for work in Russia. However all these craftsmen were arrested in Lübeck at the request of Poland and Livonia. The German merchant companies ignored the new port built by Ivan on the river Narva in 1550 and continued to deliver goods in the Baltic ports owned by Livonia. Russia remained isolated from sea trade.

Ivan formed new trading connections, opening up the White Sea and the port of Arkhangelsk to the Muscovy Company of English merchants. In 1552 his army defeated the Kazan Khanate, whose armies had repeatedly devastated the northeast of Russia,[9] and annexed its territory. In 1556, he annexed the Astrakhan Khanate and destroyed the largest slave market on the river Volga. These conquests complicated the migration of the aggressive nomadic hordes from Asia to Europe through Volga and transformed Russia into a multinational and multiconfessional state.

Ivan IV corresponded with Orthodox leaders overseas as well. In response to a letter of Patriarch Joachim of Alexandria asking the Tsar for financial assistance for the Monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai, which had suffered from the Turks, Ivan IV sent in 1558 a delegation to Egypt led by archdeacon Gennady, who, however, died in Constantinople before he could reach Egypt. From then on, the embassy was headed by a Smolensk merchant Vasily Poznyakov. Poznyakov's delegation visited Alexandria, Cairo, and Sinai, brought the patriarch a fur coat and an icon sent by the Tsar, and left an interesting account of its two and half years' travels.[10]

The Tsar had St. Basil's Cathedral constructed in Moscow to commemorate the seizure of Kazan. Legend has it that he was so impressed with the structure that he had the architect, Postnik Yakovlev, blinded, so that he could never design anything as beautiful again. In fact,[citation needed] Yakovlev went on to design more churches for Ivan and Kazan's Kremlin walls in the early 1560s, as well as the chapel over St. Basil's grave that was added to St. Basil's Cathedral in 1588, several years after Ivan's death.

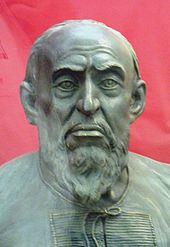

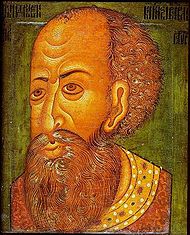

Ivan IV, parsuna, 16th-century (National Museum of Denmark)

Ivan IV, parsuna, 16th-century (National Museum of Denmark)

Other events of this period include the introduction of the first laws restricting the mobility of the peasants, which would eventually lead to serfdom, and change in Ivan's personality, traditionally linked to his near-fatal illness in 1553 and the death of his first wife, Anastasia Romanovna in 1560. Ivan suspected boyars of poisoning his wife and of plotting to replace him on the throne with his cousin, Vladimir of Staritsa. In addition, during that illness Ivan had asked the boyars to swear an oath of allegiance to his eldest son, an infant at the time. Many boyars refused, deeming the Tsar's health too hopeless for him to survive. This angered Ivan and added to his distrust of the boyars. There followed brutal reprisals and assassinations, including those of Metropolitan Philip and Prince Alexander Gorbatyi-Shuisky.

The 1565 formation of the Oprichnina was also significant. The Oprichnina was the section of Russia (mainly the Northeast) directly ruled by Ivan and policed by his personal servicemen, the Oprichniki. This system of Oprichnina has been viewed by historians as a tool against the powerful hereditary nobility of Russia (boyars) who opposed the absolutist drive of the Tsar, while some have also interpreted it as a sign of the paranoia and mental deterioration of the Tsar.

Later reign

The later half of Ivan's reign was less successful. Although Khan Devlet I Giray of Crimea repeatedly devastated the Moscow region and even set Moscow on fire in 1571, the Tsar supported Yermak's conquest of Tatar Siberia, adopting a policy of empire-building, which led him to launch an ultimately unsuccessful war of seaward expansion to the west finding himself fighting the Swedes, Lithuanians, Poles, and the Livonian Teutonic Knights.

For twenty-four years the Livonian War dragged on, damaging the Russian economy and military and failing to gain any territory for Russia. In the 1560s, Russia was devastated by the combination of drought and famine, Polish-Lithuanian raids, Tatar invasions, and the sea-trading blockade carried out by the Swedes, Poles and the Hanseatic League. The price of grain increased by a factor of ten. Epidemics of the plague killed 10,000 in Novgorod. In 1570 the plague killed 600–1000 in Moscow daily.[11] One of Ivan's advisors, Prince Andrei Kurbsky, defected to the Lithuanians, headed the Lithuanian troops and devastated the Russian region of Velikiye Luki. This treachery deeply hurt Ivan. As the Oprichnina continued, Ivan became mentally unstable and physically disabled. In one week, he could easily pass from the most depraved orgies to anguished prayers and fasting in a remote northern monastery.

Because he gradually grew unbalanced and violent, the Oprichniki under Malyuta Skuratov soon got out of hand and became murderous thugs. They massacred nobles and peasants, and conscripted men to fight the war in Livonia. Depopulation and famine ensued. What had been by far the richest area of Russia became the poorest. In a dispute with the wealthy city of Novgorod, Ivan ordered the Oprichniki to murder inhabitants of the city, and it was never to regain its former prosperity. His followers burned and pillaged Novgorod and the surrounding villages.[12] As many as 60,000 may have been killed during the infamous Massacre of Novgorod in 1570;[12][13][14] many others were deported elsewhere.[14] Yet the official death toll named 1,500 of Novgorod big people (nobility) and mentioned only about the same number of smaller people. Many modern researchers estimate number of victims between two and three thousand. (After the famine and epidemics of 1560s the population of Novgorod perhaps did not exceed 10,000–20,000.)[15]

Ioannes Basilius Magnus Imperator Russic, Dux Moscovic by Abraham Ortelius (1574)

Having rejected peace proposals from his enemies, Ivan IV found himself in a difficult position by 1579, when Crimean Khanate devastated Muscovian territories and even burned down Moscow (see Russo-Crimean Wars). The dislocations in population fleeing the war compounded the effects of the concurrently occurring drought and exacerbated war engendered epidemics causing much loss of population.

All together, the prolonged war had nearly fatally affected the economy, Oprichnina had thoroughly disrupted the government, while The Grand Principality of Lithuania had united with The Kingdom of Poland and acquired an energetic leader, Stefan Batory, who was supported by Russia's southern enemy, the Ottoman Empire (1576). Ivan's realm was now squeezed by two of the great powers of the day.

With the failure of negotiations, Batory replied with a series of three offensives against Muscovy in each campaign seasons of 1579–1581, trying to cut The Kingdom of Livonia from Muscovian territories. During his first offensive in 1579, he retook Polotsk with 22,000 men. During the second, in 1580, he took Velikie Luki with a 29,000-strong army. Finally, he started the Siege of Pskov in 1581 with a 100,000-strong army. Narva in Estonia was reconquered by Sweden in 1581.

Frederick II had trouble continuing the fight against Muscovy, unlike Sweden and Poland. He came to an agreement with John III in 1580 giving him the titles in Livonia. That war would last from 1577 to 1582. Muscovy recognized Polish-Lithuanian control of Ducatus Ultradunensis only in 1582. After Magnus von Lyffland died in 1583, Poland invaded his territories in The Duchy of Courland and Frederick II decided to sell his rights of inheritance. Except for the island of Saaremaa, Denmark was out of the Baltic by 1585. As of 1598, Polish Livonia was divided into:

- Wenden Voivodeship (województwo wendeńskie, Kieś)

- Dorpat Voivodeship (województwo dorpackie, Dorpat)

- Parnawa Voivodeship (województwo parnawskie, Parnawa)

In 1581, Ivan beat his pregnant daughter-in-law for wearing immodest clothing, and this may have caused a miscarriage. His son, also named Ivan, upon learning of this, engaged in a heated argument with his father, which resulted in Ivan striking his son in the head with his pointed staff, causing his son's (accidental) death.[citation needed] This event is depicted in the famous painting by Ilya Repin, Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan on Friday, 16 November 1581 better known as Ivan the Terrible killing his son.

Legacy

In the centuries following Ivan's death, historians developed different theories to better understand his reign, but independent of the perspective through which one chooses to approach this, it cannot be denied that Ivan the Terrible changed Russian history and continues to live on in popular imagination. His political legacy completely altered the Russian governmental structure; his economic policies ultimately contributed to the end of the Rurik Dynasty, and his social legacy lives on in unexpected places.

Arguably Ivan's most important legacy can be found in the political changes he enacted in Russia. In the words of historian Alexander Yanov, "Ivan the Terrible and the origins of the modern Russian political structure [are]... indissolubly connected." [16] At the core of this political revolution stands the newly adopted title of Tsar. By being crowned Tsar, Ivan was sending a message to the world and to Russia: he was now the one and only supreme ruler, and his will was not to be questioned. "The new title symbolized an assumption of powers equivalent and parallel to those held by former Byzantine caesar and the Tatar khan, both known in Russian sources as Tsar. The political effect was to elevate Ivan's position."[17] The new title not only secured the throne, but it also granted Ivan a new dimension of power, one intimately tied to religion. He was now a "divine" leader appointed to enact God's will, "church texts described Old Testament kings as 'Tsars' and Christ as the Heavenly Tsar."[18] The newly appointed title was then passed on from generation to generation, "succeeding Muscovite rulers...benefited from the divine nature of the power of the Russian monarch...crystallized during Ivan's reign."[19]

A title alone may hold symbolic power, but Ivan's political revolution went further, in the process significantly altering Russia's political structure. The creation of the Oprichnina marked something completely new, a break from the past that served to diminish the power of the boyars and create a more centralized government. "...the revolution of Tsar Ivan was an attempt to transform an absolutist political structure into a despotism... the Oprichnina proved to be not only the starting point, but also the nucleus of autocracy which determined... the entire subsequent historical process in Russia."[20] Ivan created a way to bypass the Mestnichestvo system and elevate the men among the gentry to positions of power, thus suppressing the aristocracy that failed to support him.[21] Part of this revolution included altering the structure of local governments to include, "a combination of centrally appointed and locally elected officials. Despite later modifications, this form of local administration proved to be functional and durable." [22] Ivan successfully cemented autocracy and a centralized government in Russia, in the process also establishing "a centralized apparatus of political control in the form of his own guard."[23] The idea of a guard as a means of political control became so ingrained in Russian history that it can be traced to Peter the Great, Vladimir Lenin, who "... [provided] Russian autocracy with its Communist incarnation",[24] and Joseph Stalin, who "[placed] the political police over the party."[24] Yanov concludes that "Czar Ivan's monstrous invention [i.e. the guard] has thus dominated the entire course of Russian history."[24]

Ivan the Terrible And His Son Ivan, 16 November 1581 by Ilya Repin, 1885 (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

Ivan the Terrible And His Son Ivan, 16 November 1581 by Ilya Repin, 1885 (Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow)

By expanding into Poland (although a failed campaign), the Caspian and Siberia, Ivan established a sphere of influence that lasted until the 20th century. Ivan's conquests also ignited a conflict with Turkey that would lead to successive wars. "Russia's victories confined the Turkish conquests to the Balkans and the Black sea region, although Turkish expansionism continued to cast a shadow over the whole of Eastern Europe."[25]

The acquisition of new territory brought about another of Ivan's lasting legacies: a relationship with Europe, especially through trade. "In 1555, Ivan IV granted the English the privilege of trading throughout his reign without paying the standard customs fees."[26] Although the contact between Russia and Europe remained small at this time, it would later grow, facilitating the permeation of European ideals across the border. Peter the Great would later push Russia to become a European power, and Catherine II would manipulate that power to make Russia a leader within the region.

Contrary to his political legacy, Ivan IV's economic legacy was disastrous and became one of the factors that led to the decline of the Rurik Dynasty and the Time of Troubles. Ivan inherited a government in debt, and in an effort to raise more revenue instituted a series of taxes. "It was the military campaigns themselves... that were responsible for the increasing government expenses."[27] Under the new political system, the Oprichniki were given large estates, but unlike the previous landlords, could not be held accountable for their actions. These men, "took virtually all the peasants possessed, forcing them to pay 'in one year as much as [they] used to pay in ten.'"[28] This degree of oppression resulted in increasing cases of peasants fleeing which in turn led to a drop in the overall production. To make matters worse, successive wars drained the country both of men and resources. "Muscovy from its core, where its centralized political structures depended upon a dying dynasty, to its frontiers, where its villages stood depopulated and its fields lay fallow, was on the brink of ruin."[29]

Ivan the Terrible meditating at the deathbed of his son. Ivan's murder of his son brought about the extinction of the Rurik Dynasty and the Time of Troubles. Painting by Vyacheslav Grigorievich Schwarz (1861).

Ivan the Terrible meditating at the deathbed of his son. Ivan's murder of his son brought about the extinction of the Rurik Dynasty and the Time of Troubles. Painting by Vyacheslav Grigorievich Schwarz (1861).

Another interesting and unexpected aspect of Ivan's social legacy emerged within Communist Russia. In an effort to revive Russia nationalist pride, Ivan the Terrible's image became closely associated with Joseph Stalin.[30]

Ivan's political revolution not only consolidated the position of Tsar, but also created a centralized government structure with ramifications extending to local government. "The assumption and active propaganda of the title of Czar, transgressions and sudden changes in policy during the Oprichnina contributed to the image of the Muscovite prince as a ruler accountable only to God."[22] Subsequent Russian rulers inherited a system put in place by Ivan.

Death

Ivan died from a stroke while playing chess with Bogdan Belsky[31] on 28 March [O.S. 18 March] 1584.[31] Upon Ivan's death, the ravaged kingdom was left to his unfit and childless son Feodor.

Ivan was a patron of the arts and himself a poet and composer of considerable talent. His Orthodox liturgical hymn, "Stichiron No. 1 in Honor of St. Peter", and fragments of his letters were put into music by Soviet composer Rodion Shchedrin. The recording was released in 1988, marking the millennium of Christianity in Russia, and was the first Soviet-produced CD.[32][33][34]

Today, there exists a controversial movement in Russia campaigning in favor of granting sainthood to Ivan IV.[35] The Russian Orthodox Church has stated its opposition to the idea.[36]

Children

- Tsarevna Anna Ivanovna

- Tsarevna Maria Ivanovna

- Tsarevich Dmitri Ivanovich

- Tsarevich Ivan Ivanovich

- Tsarevna Eudoxia Ivanovna

- Tsar Feodor I of Russia

- Tsarevich Vasili Ivanovich

- Tsarevich Dmitri Ivanovich

- Xenia Shestova (possibly)

Epistles

D.S. Mirsky called Ivan "a pamphleteer of genius". The epistles attributed to him are the masterpieces of old Russian (perhaps all Russian) political journalism. They may be too full of texts from the Scriptures and the Fathers, and their Church Slavonic is not always correct. But they are full of cruel irony, expressed in pointedly forcible terms.

The shameless bully and the great polemicist are seen together in a flash when he taunts the runaway prince Kurbsky with the question: "If you are so sure of your righteousness, why did you run away and not prefer martyrdom at my hands?" Such strokes were well calculated to drive his correspondent into a rage. "The part of the cruel tyrant elaborately upbraiding an escaped victim while he continues torturing those in his reach may be detestable, but Ivan plays it with truly Shakespearian breadth of imagination".[37] These letters are often the only existing source on Ivan's personality and provide crucial information on his reign, but Harvard professor Edward Keenan has argued that these letters are 17th century forgeries. This contention, however, has not been widely accepted, and other scholars, such as John Fennell and Ruslan Skrynnikov continued to argue for their authenticity. Recent archival discoveries of 16th century copies of the letters strengthen the argument for their authenticity.[38]

Besides his letters to Kurbsky he wrote other satirical invectives to men in his power. The best is his letter to the abbot of the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, where he pours out all the poison of his grim irony on the unascetic life of the boyars, shorn monks, and those exiled by his order. His picture of their luxurious life in the citadel of ascetism is a masterpiece of trenchant sarcasm.

Sobriquet

The English word terrible is usually used to translate the Russian word groznyi in Ivan's nickname, but the modern English usage of terrible, with a pejorative connotation of bad or evil, does not precisely represent the intended meaning. The meaning of groznyi is closer to the original usage of terrible—inspiring fear or terror, dangerous (as in Old English in one's danger), formidable or threatening. Perhaps a translation closer to the intended sense would be Ivan the Fearsome, or Ivan the Formidable.

Ancestry

Ancestors of Ivan the Terrible 16. Vasily I of Moscow 8. Vasily II of Moscow 17. Sophia of Lithuania 4. Ivan III of Russia 18. Yaroslav of Borovsk 9. Maria of Borovsk 19. Maria Goltiayeva Koshkina 2. Vasili III of Russia 20. Manuel II Palaiologos 10. Thomas Palaiologos 21. Helena Dragaš 5. Sophia (Zoe) Palaiologina 22. Centurione II Zaccaria 11. Catherine Zaccaria 23. Creusa Tocco 1. Ivan IV of Russia 24. Borys Ivanovich Glinsky 12. Lev Borysevich Glinsky 25. N. widow of Ivan Korybutovich 6. Vasili Lvovich Glinsky 3. Elena Glinskaya 28. Jakša Brežičić 14. Stefan Jakšić 7. Ana Jakšić 30. Miloš Belmužević 15. Milica Belmužević Historical censorship

Historians faced great difficulties when trying to gather information about Ivan IV in his early years because "Early Soviet historiography, especially in the 1920s, paid little attention to Ivan IV as a statesman." This, however, was not surprising because "Marxist intellectual tradition attached greater significance to socio-economic forces than to political history and the role of individuals." By the second half of the 1930s, the method used by Soviet historians changed. They placed a greater emphasis on the individual and history became more "comprehensible and accessible". The way was clear for an emphasis on 'great men', such as Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great, who made a major contribution to the strengthening and expansion of the Russian state. From this time on, the Soviet Union's focus on great leaders would be greatly exaggerated, leading historians to gather more and more information on the great Ivan the Terrible.[39]

Cinema and literature

- The Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein made two films based on the life of the Great Tsar - Ivan the Terrible. The first film is about the early progressive years of Ivan as a young tsar, it was admired by Joseph Stalin[citation needed]. The second part tells us about the cruel period of Ivan's mature age. Stalin took this film rather coldly[citation needed] as it was too much like a mirror of the Soviet regime of that time. The third one was never completed.

- Tsar – a 2009 Russian drama film directed by Pavel Lungin.

- Ivan the Terrible in Russian folklore.

- In the movie Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian Ivan was played by Christopher Guest.

- In Deadliest Warrior season 3, he fights against Hernan Cortes and loses due to an inability to lead his troops stemming from his sickness and insanity.

- Russka (1991) the novel by Edward Rutherford

See also

- Tsars of Russia family tree

- Tsardom of Russia History of the Tsardom of Russia

References

Notes

- ^ 28 March: This Date in History

- ^ Russia: Land of the Czars, History Channel

- ^ History International Channel coverage, 14:00-15:00 EDST on 10 June 2008

- ^ C. G. Jacobsen. "Myths, Politics and the Not-so-New World Order" Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 30, No. 3 (Aug., 1993), pp. 241–250; Quote from page 242: "...his governing style and system, was that of Ivan the Terrible."

- ^ Roy Temple House, Ernst Erich Noth, University of Oklahoma. Books Abroad: An International Literary Quarterly. v. 15, 1941; page 343. ISSN: 0006-7431.

- ^ Frank D. McConnell. Storytelling and Mythmaking: Images from Film and Literature. Oxford University Press, 1979. ISBN 0195025725; Quote from page 78: "But Ivan IV, Ivan the Terrible, or as the Russian has it, Ivan groznyi, "Ivan the Magnificent" or "Ivan the Great" is precisely a man who has become a legend"

- ^ Martin, Medieval Russia, 331; Pushkareva, Women in Russian History, 65–67.

- ^ Michael C. Paul, "The Military Revolution in Russia 1550–1682", The Journal of Military History 68 No. 1 (January 2004): 9–45, esp. pp. 20–22.

- ^ Russian chronicles record about forty attacks of Kazan Khans on Russian territories (mainly the regions of Nizhniy Novgorod, Murom, Vyatka, Vladimir, Kostroma, and Galich) in the first half of the 16th century. In 1521, the combined forces of Khan Mehmed Giray and his Crimean allies attacked Russia, captured more than 150,000 slaves The Full Collection of the Russian Annals, vol.13, SPb, 1904

- ^ ХОЖДЕНИЕ НА ВОСТОК ГОСТЯ ВАСИЛИЯ ПОЗНЯКОВА С ТОВАРИЩИ (The travels to the Orient by the merchant Vasily Poznyakov and his companions) (Russian)

- ^ R.Skrynnikov, "Ivan Grosny", M., AST, 2001

- ^ a b Novgorod, Russia (Capital)

- ^ Ivan the Terrible, Russia, (r.1533-84)

- ^ a b According to the Third Novgorod Chronicle, the massacre lasted for five weeks. Almost every day 500 or 600 people were killed or drowned. The First Pskov Chronicle estimates the number of victims at 60,000.

- ^ Having investigated the report of Maljuta Skuratov and commemoration lists (sinodiki), R. Skrynnikov considers, that the number of victims was 2,000–3,000. (Skrynnikov R. G., "Ivan Grosny", M., AST, 2001)

- ^ Yanov, Alexander. "The Oprichnina" in The Origins of Autocracy. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981, 31.

- ^ Martin, Janet. "Ivan IV the Terrible" in Medieval Russia 980–1584 2nd ed. 1993. Reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007, 377.

- ^ Bogatyrev, Sergei. "Ivan IV (1533–1584)". Cambridge Histories Online (2008): (accessed November 16, 2010), 245.

- ^ Bogatyrev, Sergei. "Ivan IV (1533–1584)". Cambridge Histories Online (2008): (accessed November 16, 2010), 263

- ^ Yanov, Alexander. "The Oprichnina" in The Origins of Autocracy. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981, 68.

- ^ Riasanovsky, Nicholas V., and Mark D. Steinberg. "Russia at the Time of Ivan IV, 1533–1598" in A History of Russia 8th ed. Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011, 151.

- ^ a b Bogatyrev, Sergei. "Ivan IV (1533–1584)". Cambridge Histories Online (2008): (accessed November 16, 2010), 263.

- ^ Yanov, Alexander. "The Oprichnina" in The Origins of Autocracy. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981, 69.

- ^ a b c Yanov, Alexander. "The Oprichnina" in The Origins of Autocracy. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981, 70.

- ^ Shrynnikov, Ruslan G. "Conclusion" in Ivan the Terrible, translated by Hugh F. Graham. Moscow: Academic International, 1975, 199.

- ^ Martin, Janet. "Ivan IV the Terrible" in Medieval Russia 980–1584 2nd ed. 1993. Reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007, 407.

- ^ Martin, Janet. "Ivan IV the Terrible" in Medieval Russia 980–1584 2nd ed. 1993. Reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007, 404.

- ^ Martin, Janet. "Ivan IV the Terrible" in Medieval Russia 980–1584 2nd ed. 1993. Reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007, 410.

- ^ Martin, Janet. "Ivan IV the Terrible" in Medieval Russia 980–1584 2nd ed. 1993. Reprint, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007, 415.

- ^ Maureen, Perrie. The Cult of Ivan the Terrible in Stalin's Russia. New York: Palgrava, 2001.

- ^ a b Waliszewski, Kazimierz; Mary Loyd (1904). Ivan the Terrible. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. pp. 377–78. http://books.google.com/books?id=IEEEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA377&dq=ivan+iv%2Bdeath&lr=&ei=5ykWSoKaD46UzQSs9LD0Cw.

- ^ "Иван IV Грозный / Родион Константинович Щедрин - Стихиры (Первый отечественный компакт-диск)". http://www.intoclassics.net/news/2009-08-09-7942.

- ^ "Raritet-CD". http://www.raritet-cd.ru/.

- ^ Kuzin, Viktor. "Первый русский компакт-диск". http://www.rarity.ru/CONSALTING.htm.

- ^ "Russians Laud Ivan the Not So Terrible; Loose Coalition Presses Orthodox Church to Canonize the Notorious Czar" Washington Post, 10 November 2003

- ^ "Church says nyet to St. Rasputin" UPI NewsTrack, 4 October 2004

- ^ D.S. Mirsky. A History of Russian Literature. Northwestern University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8101-1679-0. Page 21.

- ^ Edward L. Keenan, The Kurbskii-Groznyi Apocrypha: the 17th-Century Genesis of the "Correspondence" Attributed to Prince A. M. Kurbskii and Tsar Ivan IV (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1971); Janet Martin, Medieval Russia 980–1584 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 328–329.

- ^ Perrie, Maureen. The Image of Ivan the Terrible in Russian Folklore. Cambridge, UK: Pitt Building, 1987. Google Books. 2002. Web. 6 February 2011.

General references

- Bobrick, Benson. Ivan the Terrible. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 1990 (hardcover, ISBN 0-86241-288-9). (Also published as Fearful Majesty)

- Hosking, Geoffrey. Russia and the Russians: A History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004 (paperback, ISBN 0-674-01114-7).

- Madariaga, Isabel de. Ivan the Terrible. First Tsar of Russia. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2005 (hardcover, ISBN 0-300-09757-3); 2006 (paperback, ISBN 0-300-11973-9).

- Payne, Robert; Romanoff, Nikita. Ivan the Terrible. Lanham, Maryland: Cooper Square Press, 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-8154-1229-0).

- Troyat, Henri. Ivan the Terrible. New York: Buccaneer Books, 1988 (hardcover, ISBN 0-88029-207-5); London: Phoenix Press, 2001 (paperback, ISBN 1-84212-419-6).

- Ivan IV, World Book Inc, 2000. World Book Encyclopedia.

Further reading

- Cherniavsky, Michael. "Ivan the Terrible as Renaissance Prince", Slavic Review, Vol. 27, No. 2. (Jun., 1968), pp. 195–211.

- Hunt, Priscilla. "Ivan IV's Personal Mythology of Kingship", Slavic Review, Vol. 52, No. 4. (Winter, 1993), pp. 769–809.

- Perrie, Maureen. The Image of Ivan the Terrible in Russian Folklore (Cambridge Studies in Oral and Literate Culture; 14). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 (hardcover, ISBN 0-521-33075-0); 2002 (paperback, ISBN 0-521-89100-0).

- Perrie, Maureen. The Cult of Ivan the Terrible in Stalin's Russia (Studies in Russian and Eastern European History and Society) . New York: Palgrave, 2001 (hardcopy, ISBN 0-333-65684-9).

- Perrie, Maureen; Pavlov, Andrei. Ivan the Terrible (Profiles in Power). Harlow, UK: Longman, 2003 (paperback, ISBN 0-582-09948-X).

- Platt, Kevin M.F.; Brandenberger, David. "Terribly Romantic, Terribly Progressive, or Terribly Tragic: Rehabilitating Ivan IV under I.V. Stalin", Russian Review, Vol. 58, No. 4. (Oct., 1999), pp. 635–654.

External links

- "Mad Monarchs" - Ivan IV

- The throne of Ivan the Terrible

- The holy gospel of Ivan the Terrible

- The ancestors tsar Ivan IV Vasilyevich the Terrible (in the Russian languages)

- new film

- Ivan the Terrible with videos, images and translations from the Russian Archives and State Museums

- Stalin's scheme to glorify Ivan the Terrible (RT article in English)

Regnal titles Preceded by

Vasili IIIGrand Prince of Moscow

1533–1547Became Tsar New title

Become TsarTsar of Russia

1547–1584Succeeded by

Feodor IRussian royalty Preceded by

YuryHeir to the Russian Throne

1530–1533Succeeded by

Yuri Vasilyevich

Categories:- 1530 births

- 1584 deaths

- 16th-century Russian people

- Grand Princes of Moscow

- History of Russia

- Modern child rulers

- Orthodox monarchs

- Filicides

- Rurik Dynasty

- Rurikids

- Russian leaders

- Russian tsars

- Ivan the Terrible

- Folk saints

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.