- Narva

-

Narva Roundabout in Narva

Flag

Coat of armsLocation of Narva in Estonia Coordinates: 59°22′33″N 28°11′46″E / 59.37583°N 28.19611°ECoordinates: 59°22′33″N 28°11′46″E / 59.37583°N 28.19611°E Country  Estonia

EstoniaCounty  Ida-Viru County

Ida-Viru CountyFirst mentioned 1172 City rights 1345 Government – Mayor Tarmo Tammiste Area – Total 84.54 km2 (32.63 sq mi) Population (2009) – Total 65,886 – Density 779/km2 (2,019/sq mi) Time zone EET (UTC+2) – Summer (DST) EEST (UTC+3) Website www.narva.ee Narva (Russian: Нарва) is the third largest city in Estonia. It is located at the eastern extreme point of Estonia, by the Russian border, on the Narva River which drains Lake Peipus.

Contents

History

Early history

People settled in the area from the 5th to 4th millennium BC, as witnessed by the archeological traces of the Narva culture, named after the city.[1] The fortified settlement at Narva Joaoru is the oldest known in Estonia, dated to around 1000 BC.[2] The earliest written reference of Narva is in the First Novgorod Chronicle, which in the year 1172 describes a district in Novgorod called Nerevsky or Narovsky konets (yard). According to historians, this name derives from the name of Narva or Narva River and indicates that a frequently used trade route went through Narva, although there is no evidence of the existence of a trading settlement at the time.[3]

Middle Ages

The favourable location at the crossing of trade routes and the Narva River was behind the founding of Narva castle and the development of an urban settlement around it. The castle was founded during the Danish rule of northern Estonia during the second half of the 13th century, the earliest written record of the castle is from 1277.[4] Narvia village is mentioned in the Danish Census Book already in 1241. A town developed around the stronghold and in 1345 obtained Lübeck City Rights from Danish king Valdemar IV.[5] The castle and surrounding town of Narva became a possession of the Livonian Order in 1346, after the Danish king sold its lands in Northern Estonia. In 1492 Ivangorod fortress across the Narva River was established by Ivan III of Moscow.

Trade, particularly Hanseatic long distance trade remained Narva's raison d'être throughout the Middle Ages.[4] However, due to opposition from Tallinn, Narva itself never became part of the Hanseatic League and also remained a very small town – its population in 1530 is estimated at 600–750 people.[4]

Swedish and Russian rule

Captured by the Russians during the Livonian War in 1558, for a short period Narva became an important port and trading city for Russia, transshipping goods from Pskov and Novgorod. Russian rule ended in 1581 when Swedes under the command of Pontus De la Gardie conquered the city and it became part of Sweden. During the Russo-Swedish War (1590–1595), when Arvid Stålarm was governor, Russian forces attempted to re-gain the city without success.

Peter I of Russia pacifies his marauding troops after taking Narva in 1704 by Nikolay Sauerweid, 1859

Peter I of Russia pacifies his marauding troops after taking Narva in 1704 by Nikolay Sauerweid, 1859

During the Swedish rule the Old Town of Narva was built. Following a big fire in 1659, which almost completely destroyed the town, only stone buildings were allowed to be built in the central part of the town. Incomes from flourishing trade allowed the town center to be rebuilt in two decades.[5] The baroque style Old Town underwent practically no changes until World War II and became in later centuries quite famous all over Europe. Near the end of the Swedish rule the defence structures of Narva were greatly improved – beginning in 1680s, an outstanding system of bastions, planned by the renowned Swedish military engineer Erik Dahlbergh, was built around the town. The new defence structures were among the most powerful in Northern Europe.[5]

During the Great Northern War, Narva was the setting for its first great battle between the forces of King Charles XII of Sweden and Tsar Peter I of Russia. Although outnumbered four to one, the Swedish forces routed their 40 000-strong opponent. The city was subsequently conquered by Russia in 1704.

After the war the bastions were renovated and Narva remained in the list of Russian fortifications until 1863, though there was no real military need for it.[5] During the Russian rule Narva was part of Saint Petersburg Governorate.

In the middle of the 19th century Narva started to develop into a major industrial town. The Kreenholm Manufacture was established by Ludwig Knoop in 1857. The factory could use the cheap energy of the powerful Narva waterfalls and at the end of the century became, with about 10,000 workers, one of the largest cotton mills in Europe and the World.[6] In 1872 Kreenholm Manufacture was also the site of the first strike in Estonia.[7] At the end of the 19th century, Narva was the leading industrial town in Estonia – 41% of industrial workers in Estonia were located in Narva, compared to 33% in Tallinn.[7] The first railway in Estonia, completed in 1870, connected Narva to Saint Petersburg and Tallinn.

20th century

Narva became part of independent Estonia in 1918 following World War I. The town saw fighting during the Estonian War of Independence. The war started in Narva on 28 November 1918, on the next day the city was captured by the Red Army. Russia retained control of the city until 19 January 1919.[8]

Heavy battles occurred in and around Narva in World War II (see Battle of Narva (1944)), during which the city was almost completely leveled. The city was damaged in 1941 and by smaller air raids throughout the war, but remained relatively intact until February 1944.[9] The most devastating action was the bombing of 6 March 1944 by the Soviet Air Force, which destroyed the baroque old town.[5] The civilian casualties of the bombing were low as the German forces had evacuated the city in January the same year. Germans also blew up some of the remaining buildings and by their retreat in the end of July 98% of Narva had been destroyed.[9] After the war, most of the buildings could have been restored as the walls of the houses still existed, but in early 1950s the Soviet authorities decided to demolish the ruins to make room for apartment buildings. Only three buildings remain of the old town, including the Baroque-style Town Hall.[10]

The former inhabitants were not allowed to return to Narva after the war. The main reason behind this was a plan to build a secret uranium processing plant in the city, which would turn Narva into a closed town. Although already in 1947 nearby Sillamäe was selected as the location of the factory instead of Narva, the existence of such plan was decisive for the development of Narva in the first post-war years and thus also shaped its later evolution.[11] The planned uranium factory and other large-scale industrial developments, like the restoring of Kreenholm Manufacture, were the driving force behind the influx of internal migrants from other parts of the Soviet Union, mainly Russia.[11]

In January 1945 Ivangorod, a town across the river which was founded in 1492 by Tsar Ivan III of Russia, was given a separate administrative status from the rest of Narva, as a part of the Leningrad Oblast in the Russian SFSR. Ivangorod received the official status of town in 1954.

Recent history

When Estonia regained its independence in 1991, Narva became again a border city. As the population of Narva was dominated by Soviet-era migrants from Russia and other union republics, the fall of the Soviet Union and re-established Republic of Estonia were not especially greeted in the city and other industrial towns of the Ida-Viru County. The dissatisfaction culminated with the so-called Narva referendum of 16–17 July 1993, which proposed autonomy for Narva and Sillamäe, another nearby industrial town.[12] The Estonian government deemed the referendum illegal and sent Indrek Tarand as its special envoy to the region.[13] The referendum was indeed carried out, but generally failed as it did not provide a clear popular mandate for the autonomy,[12] leading to the stabilization of the situation.[13]

After 1991 there have also been some disputes about the Estonian-Russian border in the Narva area, as the new constitution of Estonia (adopted in 1992) recognizes the 1920 Treaty of Tartu border to be currently legal. The Russian Federation, however, considers Estonia to be a successor of the Estonian SSR and recognizes the 1945 border between two former national republics. Officially, Estonia has no territorial claims in the area,[14][15][16] which is also reflected in the new Estonian-Russian border treaty. Although the treaty was signed in 2005 by the foreign ministers of Estonia and Russia, due to continuing political tensions it has not been ratified.

Demographics

On 1 January 2009 Narva had 65,886 inhabitants. The population, which was 83,000 in 1992, has been declining since then.[17] 93.85% of the current population of Narva are Russian-speakers (80% are ethnic Russians[17]), mostly either Soviet-era immigrants from parts of the former Soviet Union (mainly Russia) or their descendants. Estonians account for only 4% of total population.[17] Much of the city was destroyed during World War II and for several years during the following reconstruction the Soviet authorities prohibited the return of any of Narva's pre-war residents (among whom ethnic Estonians had been the majority, forming 64.8% of the town's population of 23,512 according to the 1934 census[18]), thus radically altering the city's ethnic composition.[7]

Only 46% of the city's inhabitants are Estonian citizens. Another 35% are citizens of the Russian Federation, while 18% of the population has undefined citizenship.[17]

A significant concern in Narva is the spread of HIV, which started expanding in 2000. Between 2001 and 2008, more than 1600 cases of HIV were registered in Narva, making it one of the three areas worst hit in Estonia, after Tallinn and ahead of the rest of Ida-Viru County.[19] On average 150–200 new cases have been registered yearly.

Geography and climate

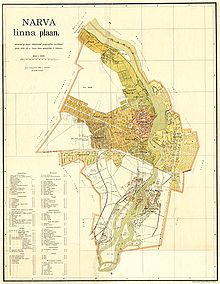

Narva is situated in the eastern extreme point of Estonia, 200 km to the east from the Estonian capital Tallinn and 130 km southwest from Saint Petersburg. The capital of Ida-Viru County, Jõhvi, lies 50 km to the west. The eastern border of the city along the Narva River coincides with the Estonian-Russian border. The Estonian part of the Narva Reservoir lies mostly within the territory of Narva, to the southwest of city center. The mouth of the Narva River to the Gulf of Finland is about 13 km downstream from the city.

The territory of Narva is 84.54 km2. The city proper has an area of 62 km2 (excluding the reservoir), while two separate districts surrounded by Vaivara Parish, Kudruküla and Olgina, cover 5.6 and 0.58 km2, respectively.[20] Kudruküla is the largest of Narva's dacha regions, located 6 km to northwest from the main city, near Narva-Jõesuu.

Narva Climate chart (explanation) J F M A M J J A S O N D 30−5−1124−4−11291−636804216553209762112862011851496593532−244−2−7Average max. and min. temperatures in °C Precipitation totals in mm Source: EMHI (1961–1990) Imperial conversion J F M A M J J A S O N D 1.223120.925121.134211.446321.761412.16848370543.468523.357482.648372.136281.72819Average max. and min. temperatures in °F Precipitation totals in inches Landmarks

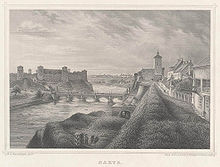

The reconstructed fortress of Narva (to the left) overlooking the Russian fortress of Ivangorod (to the right).

The reconstructed fortress of Narva (to the left) overlooking the Russian fortress of Ivangorod (to the right).

Narva is dominated by the 15th-century castle, with the 51-metre-high Long Hermann tower as its most prominent landmark. The sprawling complex of the Kreenholm Manufacture, located in the proximity of scenic waterfalls, is one of the largest textile mills of 19th-century Northern Europe. Other notable buildings include Swedish mansions of the 17th century, a Baroque town hall (1668–71), and remains of Erik Dahlberg's fortifications.[citation needed]

Across the Narva River is the Russian Ivangorod fortress, founded by Grand Prince Ivan III of Muscovy in 1492 and known in Western sources as Counter-Narva. During the Soviet times Narva and Ivangorod were twin cities, despite belonging to different republics. Before World War II, Ivangorod (Estonian: Jaanilinn) was administrated as part of Narva.

Narva Kreenholmi Stadium is home to Meistriliiga football team, FC Narva Trans.

Notable residents

- Maksim Gruznov (born 1974), football player

- Evert Horn (1585–1615), governor of Narva (1613)

- Valery Karpin (born 1969), Russian football player

- Paul Keres (1916–1975), chess grandmaster

- Leo Komarov (born 1987), hockey player

- Friedrich Lustig (1912–1989), Buddhist monk

- William Kleesmann Matthews (1901–1958), linguist, translator and writer

- Kersti Merilaas (1913–1986), poetess, playwright

- Ortvin Sarapu (1924–1999), chess player

- Paul Felix Schmidt (1916–1984), chess player

- Albert Üksip (1886–1966), botanist

International relations

See also: List of twin towns and sister cities in EstoniaTwin towns — Sister cities

Narva is twinned with:

References

- ^ "History of Narva: Formation of city". Narva Museum. http://www.narvamuuseum.ee/?next=kujunemine&lang=eng&menu=menu_ajalugu. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ Kriiska, Aivar; Lavento, Mika (2006). "Narva Joaoru asulakohalt leitud keraamika kõrbekihi AMS-dateeringud" (in Estonian (with summary in English and Russian)). Narva Muuseumi toimetised (6). https://www.etis.ee/ShowFile.aspx?FileVID=15962.

- ^ Raik, Katri (2005). "Miks pidada linna, eriti Narva sünnipäeva?" (in Estonian). Narva Muuseumi toimetised (5).

- ^ a b c Kivimäe, Jüri (2004). "Medieval Narva: Featuring a Small Town between East and West". In Brüggemann, Karsten. Narva and the Baltic Sea Region. Narva: Narva College of the University of Tartu. ISBN 9985404173.

- ^ a b c d e "History of Narva: Narva fortifications and Narva Castle". Narva Museum. http://www.narvamuuseum.ee/?lang=eng&next=linnus&menu=menu_ajalugu. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ "History of Narva: Timeline". Narva Museum. http://www.narvamuuseum.ee/?lang=eng&next=kronoloogia&menu=menu_ajalugu. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ^ a b c Raun, Toivo U. (2001). Estonia and the Estonians. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University. ISBN 0817928529. http://books.google.com/?id=YQ1NRJlUrwkC&printsec=frontcover.

- ^ (in Russian) Нарва: культурно-исторический справочник [Narva: kulturno-istoricheskiy spravochnik]. Narva: Narva Museum. 2001.

- ^ a b Kattago, Siobhan (2008). "Commemorating Liberation and Occupation: War Memorials Along the Road to Narva". Journal of Baltic Studies 39 (4): 431–449. doi:10.1080/01629770802461225. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a906693040~db=all~order=page.

- ^ "History of Narva: The Old Town of Narva". Narva Museum. http://www.narvamuuseum.ee/?next=vanalinn&lang=eng&menu=menu_ajalugu. Retrieved 2009-03-19.

- ^ a b Vseviov, David (2001) (in Estonian (with Russian summary)). Nõukogudeaegne Narva. Elanikkonna kujunemine 1944–1970. Tartu: Okupatsioonide Repressiivpoliitika Uurimise Riiklik Komisjon.

- ^ a b Batt, Judy; Wolczuk, Kataryna, ed (2002). Region, state and identity in Central and Eastern Europe. London, Portland: Frank Cass Publishers. pp. 222. ISBN 0714652431. http://books.google.com/?id=sw72GPjF0DYC&pg=PA98&lpg=PA98&dq=narva+referendum&q=narva%20referendum. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ^ a b Tarand, Indrek (2008-07-16). ""Võta naine, kui võimalik, Narvast…" (R. Valgre)" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht. http://www.epl.ee/artikkel/435541. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ^ "Estonia and Russia: Treaties". Estonian Foreign Ministry. http://www.vm.ee/?q=en/node/93#treaties. Retrieved 2009-11-12. "Estonia sticks to its former position that it has no territorial claims with respect to Russia, and Estonia sees no obstacles for the entry into force of the current treaty."

- ^ Berg, Eiki. "Milleks meile idapiir ja ilma lepinguta?" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht. http://www.epl.ee/artikkel/400839. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ "Enn Eesmaa: väide Petseri-soovist on ennekõike provokatiivne" (in Estonian). Eesti Päevaleht. http://www.epl.ee/artikkel/476082. Retrieved 2009-09-27.

- ^ a b c d e f "Narva in figures 2008". Narva City Government. http://web.narva.ee/files/Narva_arvudes_2008.pdf. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- ^ (in Estonian and French) Rahvastiku koostis ja korteriolud. 1.III 1934 rahvaloenduse andmed. Vihk II. Tallinn: Riigi Statistika Keskbüroo. 1935. hdl:10062/4439.

- ^ HIV statistics for Estonia: 2001–2006, 2007, 2008

- ^ Narva LV Arhitektuuri- ja Linnaplaneerimise Amet (in Estonian)

External links

Cities and towns (Linnad) of Estonia Abja-Paluoja · Antsla · Elva · Haapsalu · Jõgeva · Jõhvi · Kallaste · Kärdla · Karksi-Nuia · Kehra · Keila · Kilingi-Nõmme · Kiviõli · Kohtla-Järve · Kunda · Kuressaare · Lihula · Loksa · Maardu · Mõisaküla · Mustvee · Narva · Narva-Jõesuu · Otepää · Paide · Paldiski · Pärnu · Põltsamaa · Põlva · Püssi · Rakvere · Räpina · Rapla · Saue · Sillamäe · Sindi · Suure-Jaani · Tallinn · Tamsalu · Tapa · Tartu · Tõrva · Türi · Valga · Viljandi · Võhma · Võru

Jaanilinn (Ivangorod) and Petseri (Pechory) were annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945 and are currently part of Russia.

Jaanilinn (Ivangorod) and Petseri (Pechory) were annexed by the Soviet Union in 1945 and are currently part of Russia. Municipalities of Ida-Viru County

Municipalities of Ida-Viru CountyUrban municipalities

Rural municipalities Placename toponym Narva Outpost in St. Petersburg · Narva Triumphal Gate · Subway station · Square Categories:- Narva

- Cities and towns in Estonia

- Estonia–Russia border crossings

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.