- Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence

-

Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS) is the name Aubrey de Grey gives to his proposal to research regenerative medical procedures to periodically repair all the age-related damage in the human body, thereby maintaining a youthful state indefinitely.[1][2] The term first appeared in print in de Grey's 1999 book The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging,[3] and was later prefaced with the term "strategies" in the article Time to Talk SENS: Critiquing the Immutability of Human Aging[4] De Grey argues for a "goal-directed rather than curiosity-driven"[5] approach to the science of aging, and to this purpose he tentatively identifies seven "damages of aging" and their potential methods of treatments.

SENS has received media attention[6][7][8] but has been criticized by some scientists.[who?] While many biogerontologists (scientists who study aging) find it "worthy of discussion"[9][10] and SENS conferences feature important research in the field,[11][12] some contend that de Grey's programme is too speculative given current scientific research, referring to it as "fantasy rather than science".[13][14]

Contents

Framework

The goal of the Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS) is the complete reversal of all age-related illnesses and indefinite extension of the healthy human lifespan.[1] The SENS project consists in implementing a series of periodic medical interventions designed to repair, prevent or render irrelevant all the types of molecular and cellular damage that cause age-related pathology and degeneration, in order to avoid debilitation and death from age-related causes.[2]

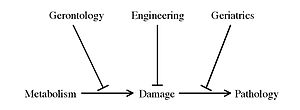

De Grey defines aging as "the set of accumulated side effects from metabolism that eventually kills us",[15] and, more specifically, as follows: "a collection of cumulative changes to the molecular and cellular structure of an adult organism, which result in essential metabolic processes, but which also, once they progress far enough, increasingly disrupt metabolism, resulting in pathology and death."[16]

As de Grey states, "geriatrics is the attempt to stop damage from causing pathology; traditional gerontology is the attempt to stop metabolism from causing damage; and the SENS (engineering) approach is to eliminate the damage periodically, so keeping its abundance below the level that causes any pathology."[1] His approach to biomedical gerontology ("anti-aging medicine") is thus distinctive because of its emphasis on rejuvenation rather than attempting to slow the aging process.

He identifies what he believes to be the seven biological causes of senescence.[2][17] According to de Grey, the causes of aging in humans are:

- cell loss or atrophy (without replacement)[4][16][18]

- oncogenic nuclear mutations and epimutations,[19][20][21]

- cell senescence (Death-resistant cells),[22][23]

- mitochondrial mutations,[24][25]

- Intracellular junk or junk inside cells (lysosomal aggregates),[26][27]

- extracellular junk or junk outside cells (extracellular aggregates),[22][23]

- random extracellular cross-linking.[22][23]

For each of these problems, de Grey outlines possible solutions, with a research and a clinical component. The clinical component is required because in some of the proposed therapies, feasibility has already been proven, but not completely applied and approved for use by human beings. He believes we will be able to apply these solutions before we completely understand the targeted aging mechanisms, which will take longer.[15] He states that the goals work together to eliminate known causes of human senescence, are concrete, seem achievable, and are considered feasible by experts in the applicable fields. The goals were said to be taken from classical literature describing the biological causes of senescence.

De Grey proposes that engineered negligible senescence therapies could extend the human lifetime by many centuries or millennia, as early therapies give them enough time to seek more effective therapies later on. He describes an actuarial escape velocity of life extension, when advances in senescence treatment come rapidly enough to save the lives of the oldest beneficiaries of the previous treatments.[28]

Types of aging damage and treatment schemes

Cancer-causing nuclear mutations/epimutations—OncoSENS

These are changes to the nuclear DNA (nDNA), the molecule that contains our genetic information, or to proteins which bind to the nDNA. Certain mutations can lead to cancer, and, according to de Grey, non-cancerous mutations and epimutations do not contribute to aging within a normal lifespan, so cancer is the only endpoint of these types of damage that must be addressed. A mutation in a functional gene of a cell can cause that cell to malfunction or to produce a malfunctioning product, because of the sheer number of cells, de Grey believes that redundancy takes care of this problem, although cells that have mutated to produce toxic products might have to be disabled. In de Grey's opinion, the effect of mutations and epimutations that really matters is cancer, this is because if even one cell turns into a cancer cell it might spread and become deadly. This would need to be corrected by a cure for cancer, if any is ever found. The SENS program focuses on a strategy called "whole-body interdiction of lengthening telomeres" (WILT), which would be made possible by periodic regenerative medicine treatments (see below). Restoring telomeres would protect the ends of DNA from being cut off after successive divisions since each one normally removes some which is at first the telomere.

Mitochondrial mutations—MitoSENS

Mitochondria are components in our cells that are important for energy production. They contain their own genetic material, and mutations to their DNA can affect a cell’s ability to function properly. Indirectly, these mutations may accelerate many aspects of aging. Because of the highly oxidative environment in mitochondria and their lack of the sophisticated repair systems found in cell nucleus, mitochondrial mutations are believed to a be a major cause of progressive cellular degeneration. This would be corrected by allotopic expression—moving the DNA for mitochondria completely within the cellular nucleus, where it is better protected. In humans, all but 13 proteins are already protected in this way. De Grey argues that experimental evidence demonstrates that the operation is feasible. However, a 2003 study showed that some mitochondrial proteins are too hydrophobic to survive the transport from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria,[29] and this is perhaps one of the reasons that not all of the mitochondrial genes have migrated to the nucleus during the course of evolution.

Intracellular junk—LysoSENS

Our cells are constantly breaking down proteins and other molecules that are no longer useful or which can be harmful. Those molecules which can’t be digested simply accumulate as junk inside our cells, which is readily detected in the form of lipofuscin granules. Atherosclerosis, macular degeneration, liver spots on the skin and all kinds of neurodegenerative diseases (such as Alzheimer's disease) are associated with this problem. Junk inside cells might be removed by adding new enzymes to the cell's natural digestion organ, the lysosome. These enzymes would be taken from bacteria, molds and other organisms that are known to completely digest animal bodies.

Extracellular junk—AmyloSENS

Harmful junk protein can also accumulate outside of our cells. Junk outside cells might be removed by enhanced phagocytosis (the normal process used by the immune system), and small drugs able to break chemical beta-bonds. The large junk in this class can be removed surgically. Junk here means useless things accumulated by a body, but which cannot be digested or removed by its processes, such as the amyloid plaques characteristic of Alzheimer's disease and other amyloidoses. The oft-mentioned "toxins" that are identified as causes of many diseases most likely fit under this class.

Cell loss and atrophy—RepleniSENS

Some of the cells in our bodies cannot be replaced, or can be only replaced very slowly—more slowly than they die. This decrease in cell number affects some of the most important tissues of the body. Muscle cells are lost in skeletal muscles and the heart, causing them to become frailer with age. Loss of neurons in the substantia nigra causes Parkinson's disease, while loss of immune cells impairs the immune system. Cell depletion can be partly corrected by therapies involving exercise and growth factors. But stem cell therapy, regenerative medicine and tissue engineering are almost certainly required for any more than just partial replacement of lost cells. De Grey points out that this research of stem cell treatments is playing an increasingly important role in the international scientific community and progress is already occurring on many fronts. However, a large number of details are involved, and most such treatments are still experimental.

Cell senescence—ApoptoSENS

This is a phenomenon where the cells are no longer able to divide, but also do not die and let others divide. They may also do other things that they are not supposed to do, like secreting proteins that could be harmful. Degeneration of joints, immune senescence, accumulation of visceral fat and type 2 diabetes are caused by this. Cells sometimes enter a state of resistance to signals sent, as part of a process called apoptosis, to instruct cells to destroy themselves. An example is the state known as cellular senescence. Cells in this state could be eliminated by forcing them to apoptose, and healthy cells would multiply to replace them. Cell killing with suicide genes or vaccines is suggested for making the cells undertake apoptosis.

Extracellular crosslinks—GlycoSENS

Cells are held together by special linking proteins. When too many cross-links form between cells in a tissue, the tissue can lose its elasticity and cause problems including arteriosclerosis, presbyopia and weakened skin texture.[15] These are chemical bonds between structures that are part of the body, but not within a cell. In senescent people many of these become brittle and weak. De Grey proposes to further develop small-molecular drugs and enzymes to break links caused by sugar-bonding, known as advanced glycation endproducts, and other common forms of chemical linking.

Scientific controversy

While some fields mentioned as branches of SENS are broadly supported by the medical research community, i.e. stem cell research (RepleniSENS), anti-Alzheimers research (AmyloSENS) and oncogenomics (OncoSENS), the SENS programme as a whole has been a highly controversial proposal, with many critics arguing that the SENS agenda is fanciful and the highly complicated biomedical phenomena involved in the aging process contain too many unknowns for SENS to be scientific or implementable in the foreseeable future. Cancer may well deserve special attention as an aging-associated disease (OncoSENS), but the SENS claim that nuclear DNA damage only matters for aging because of cancer has been challenged.[30]

In November 2005, 28 biogerontologists published a statement of criticism in EMBO reports, "Science fact and the SENS agenda: what can we reasonably expect from ageing research?,"[31] arguing "each one of the specific proposals that comprise the SENS agenda is, at our present stage of ignorance, exceptionally optimistic,"[31] and that some of the specific proposals "will take decades of hard work [to be medically integrated], if [they] ever prove to be useful."[31] The researchers argue that while there is "a rationale for thinking that we might eventually learn how to postpone human illnesses to an important degree,"[31] increased basic research, rather than the goal-directed approach of SENS, is presently the scientifically appropriate goal. This article was written in response to a July 2005 EMBO reports article previously published by de Grey[32] and a response from de Grey was published in the same November issue.[33] De Grey summarizes these events in "The biogerontology research community's evolving view of SENS," published on the Methuselah Foundation website.[34]

De Grey Technology Review controversy

Main article: De Grey Technology Review controversyIn February 2005, Technology Review, which is owned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, published an article by Sherwin Nuland, a Clinical Professor of Surgery at Yale University and the author of "How We Die",[35] that drew a skeptical portrait of Aubrey de Grey, at the time a computer associate in the Flybase Facility of the Department of Genetics at the University of Cambridge.[36] While admiring de Grey's intelligence, Nuland concluded that he "would surely destroy us in attempting to preserve us"[37] because living for such long periods would undermine what it means to be human.[37] In the same issue of the magazine, Jason Pontin, the editor in chief and publisher of Technology Review, criticised de Grey. Writing an editor's letter, titled Against Transcendence, he questioned the usefulness and appropriateness of introducing transcendentalism, or transhumanism, into science.[38] The April 2005 issue of Technology Review contained a reply by Aubrey de Grey[39] and numerous comments from readers.[40]

During June 2005 David Gobel, CEO and Co-founder of Methuselah Foundation offered Technology Review $20,000 to fund a prize competition to publicly clarify the viability of the SENS approach. In July 2005, Pontin announced a $20,000 prize, funded 50/50 by Methuselah Foundation and MIT Technology Review, open to any molecular biologist, with a record of publication in biogerontology, who could prove that SENS was "so wrong that it is unworthy of learned debate."[41] Technology Review received five submissions to its Challenge. In March, of 2006, Technology Review announced that it had chosen a panel of judges for the Challenge.[42] Three met the terms of the prize competition. They were published by Technology Review on June 9, 2006. Accompanying the three submissions were rebuttals by de Grey, and counter-responses to de Grey's rebuttals. On July 11, 2006, Technology Review published the results of the SENS Challenge.[9][43]

In the end, no one won the $20,000 prize. The judges felt that no submission met the criterion of the challenge and disproved SENS, although they unanimously agreed that one submission, by Preston Estep and his colleagues, was the most eloquent. Craig Venter succinctly expressed the prevailing opinion: "Estep et al. ... have not demonstrated that SENS is unworthy of discussion, but the proponents of SENS have not made a compelling case for it."[9] Summarizing the judges' deliberations, Pontin wrote, "SENS is highly speculative. Many of its proposals have not been reproduced, nor could they be reproduced with today's scientific knowledge and technology. Echoing Myhrvold, we might charitably say that de Grey's proposals exist in a kind of antechamber of science, where they wait (possibly in vain) for independent verification. SENS does not compel the assent of many knowledgeable scientists; but neither is it demonstrably wrong."[9][10] In a letter of dissent dated July 11, 2006 in Technology Review, Estep et al. criticized the ruling of the judges.

Social and economic implications

According to de Grey, of the roughly 150,000 people who die each day across the globe, about two thirds — 100,000 per day — die of age-related causes.[44] In industrialized nations, the proportion is much higher, reaching 90%.[44]

De Grey and other scientists in the general field have argued that the costs of a rapidly growing aging population will increase to the degree that the costs of an accelerated pace of aging research are easy to justify in terms of future costs avoided. Olshansky et al. 2006 argue, for example, that the total economic cost of Alzheimer's disease in the US alone will increase from $80–100 billion today to more than $1 trillion in 2050.[45] "Consider what is likely to happen if we don't [invest further in aging research]. Take, for instance, the impact of just one age-related disorder, Alzheimer disease (AD). For no other reason than the inevitable shifting demographics, the number of Americans stricken with AD will rise from 4 million today to as many as 16 million by midcentury. This means that more people in the United States will have AD by 2050 than the entire current population of the Netherlands. Globally, AD prevalence is expected to rise to 45 million by 2050, with three of every four patients with AD living in a developing nation. The US economic toll is currently $80–$100 billion, but by 2050 more than $1 trillion will be spent annually on AD and related dementias. The impact of this single disease will be catastrophic, and this is just one example."[45]

SENS meetings

There have been four SENS roundtables and four SENS conferences held.[46] The first SENS roundtable was held in Oakland, California on October, 2000,[47] and the last SENS roundtable was held in Bethesda, Maryland on July, 2004.[48]

On March 30–31, 2007 a North American SENS symposium was held in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada as the Edmonton Aging Symposium.[49][50] Another SENS-related conference ("Understanding Aging") was held at UCLA in Los Angeles, California on June 27-29, 2008[51]

Four SENS conferences have been held at Queens' College, Cambridge in England. All the conferences were organized by de Grey and all featured world-class researchers in the field of biogerontology. The first SENS conference was held in September 2003 as the 10th Congress of the International Association of Biomedical Gerontology[52] with the proceedings published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.[53] The second SENS conference was held in September 2005 and was simply called Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS), Second Conference[54] with the proceedings published in Rejuvenation Research. The third SENS conference was held in September, 2007.[55] The fourth SENS conference was held September 3–7, 2009 and, like the first three, it was at Queens' College, Cambridge in England, organized by de Grey.[56][57] Videos of the presentations are available.[58] A fifth SENS conference was held August 31 to September 3, 2011 at Queens' College, Cambridge in England.[59]

SENS Foundation

Main article: SENS FoundationThe SENS Foundation is a non-profit organization co-founded by Michael Kope, Aubrey de Grey, Jeff Hall, Sarah Marr and Kevin Perrott, which is based in California, United States. Its activities include SENS-based research programs and public relations work for the acceptance of and interest in scientific anti-aging research.

Before March 2009, the SENS research programme was mainly pursued by the Methuselah Foundation, co-founded by Aubrey de Grey and David Gobel. The Methuselah Foundation is most notable for establishing the Methuselah Mouse Prize, a monetary prize awarded to researchers who extend the lifespan of mice to unprecedented lengths.[60]

See also

- Actuarial escape velocity

- Aging-associated diseases

- List of life extension topics

- Pro-aging trance

- Rejuvenation Research

- Protoscience

- American Academy of Anti-Aging Medicine

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b c "The SENS Platform: An Engineering Approach to Curing Aging". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on June 28, 2008.

- ^ a b c de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (September 2007). Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 416 pp. ISBN 0312367066.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (November 2003). The Mitochondrial Free Radical Theory of Aging. Austin, Texas: Landes Bioscience. ISBN 1587061554.

- ^ a b de Grey AD, Ames BN, Andersen JK, Bartke A, Campisi J, Heward CB, McCarter RJ, Stock G (April 2002). "Time to Talk SENS: Critiquing the Immutability of Human Aging". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 959: 452–62. PMID 11976218.

- ^ Bulkes, Nyssa (March 6, 2006). "Anti-aging research breakthroughs may add up to 25 years to life". The Northern Star. Northern Illinois University (DeKalb, USA).

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (December 3, 2004). "We will be able to live to 1,000". BBC News.

- ^ Gorman, James (November 1, 2003). "High-Tech Daydreamers Investing In Immortality". The New York Times.

- ^ Ferguson, Bruce (January 1, 2006). "The Quest for Immortality". 60 Minutes. CBS News.

- ^ a b c d Pontin, Jason (July 11, 2006). "Is Defeating Aging Only A Dream?". Technology Review.

- ^ a b Garreau, Joel (October 31, 2007). "Invincible Man". Washington Post.

- ^ Fourth SENS Conference (2009). Over 140 Accepted Abstracts. Cambridge, England, September 3–7th, 2009.

- ^ Kristen Fortney (2009). SENS4 Conference Coverage From Ouroboros. FightAging.org, September 4, 2009.

- ^ Warner H, Anderson J, Austad S, et al. (November 2005). "Science fact and the SENS agenda. What can we reasonably expect from ageing research?". EMBO Reports 6 (11): 1006–8. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400555. PMC 1371037. PMID 16264422. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1371037.

- ^ Holliday R (April 2009). "The extreme arrogance of anti-aging medicine". Biogerontology 10 (2): 223–8. doi:10.1007/s10522-008-9170-6. PMID 18726707.

- ^ a b c Than, Ker (April 11, 2005). "Hang in There: The 25–Year Wait for Immortality". LiveScience. Imaginova.

- ^ a b de Grey, Aubrey (January 8, 2003). "An engineer's approach to the development of real anti-aging medicine". Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2003 (1): VP1. doi:10.1126/sageke.2003.1.vp1. PMID 12844502.

- ^ Hooper, Joseph (January 1, 2005). "The Prophet of Immortality". POPSCI.COM.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (2005). "A strategy for postponing aging indefinitely". Stud Health Technol Inform. 118: 209–19. PMID 16301780.

- ^ de Grey AD, Campbell FC, Dokal I, Fairbairn LJ, Graham GJ, Jahoda CA, Porterg AC (June 2004). Total deletion of in vivo telomere elongation capacity: an ambitious but possibly ultimate cure for all age-related human cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1019: 147–70. doi:10.1196/annals.1297.026. PMID 15247008.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (September 1, 2005). "Whole-body interdiction of lengthening of telomeres: a proposal for cancer prevention". Frontiers in Bioscience. 10: 2420–29. PMID 15970505.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (July–August 2007). "Protagonistic pleiotropy: Why cancer may be the only pathogenic effect of accumulating nuclear mutations and epimutations in aging". Mech Ageing Dev. 128 (7–8): 456–59. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2007.05.005. PMID 17588643.

- ^ a b c de Grey, Aubrey (February 2003). "Challenging but essential targets for genuine anti-ageing drugs". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 7 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1517/14728222.7.1.1. PMID 12556198.

- ^ a b c de Grey, Aubrey (November 2006). "Foreseeable pharmaceutical repair of age-related extracellular damage". Curr Drug Targets. 7 (11): 1469–77. ISSN 1389–4501. PMID 17100587.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (Fall 2004). "Mitochondrial Mutations in Mammalian Aging: An Over-Hasty About-Turn?" Rejuvenation Res. 7 (3): 171–4. doi:10.1089/rej.2004.7.171. PMID 15588517.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (September 2000). "Mitochondrial gene therapy: an arena for the biomedical use of inteins". Trends Biotechnol. 18 (9): 394–99. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(00)01476-1". PMID 10942964.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (November 2002). "Bioremediation meets biomedicine: therapeutic translation of microbial catabolism to the lysosome". Trends Biotechnol. 20 (11): 452–5. doi:10.1016/S0167-7799(02)02062-0. PMID 12413818.

- ^ de Grey AD, Alvarez PJJ, Brady RO, Cuervo AM, Jerome WG, McCarty PL, Nixon RA, Rittmann BE, Sparrow JR (August 2005). "Medical bioremediation: prospects for the application of microbial catabolic diversity to aging and several major age-related diseases". Ageing Research Reviews. 4 (3): 315–38. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2005.03.008. PMID 16040282.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (June 15, 2004). "Escape Velocity: Why the Prospect of Extreme Human Life Extension Matters Now". PLOS Biology 2 (6): 723–26. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020187.

- ^ Oca-Cossio, J. et al., 2003. Limitations of Allotopic Expression of Mitochondrial Genes in Mammalian Cells. Genetics, 165(2), 707-720.

- ^ Best, BP (2009). "Nuclear DNA damage as a direct cause of aging" (PDF). Rejuvenation Research 12 (3): 199–208. doi:10.1089/rej.2009.0847. PMID 19594328. http://www.benbest.com/lifeext/Nuclear_DNA_in_Aging.pdf.

- ^ a b c d Warner H et al. (November 2005). "Science fact and the SENS agenda. What can we reasonably expect from ageing research?". EMBO reports. 6 (11): 1006–1008. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400555. PMID 16264422.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (July 2005). "Resistance to debate on how to postpone ageing is delaying progress and costing lives". EMBO reports. 6 (S1): S49–S53. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400399. PMID 15995663.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (November 2005). "Like it or not, life-extension research extends beyond biogerontology". EMBO reports. 6 (11): 1000. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400565. PMID 16264420.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey. "The biogerontology research community's evolving view of SENS". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ Nuland, Sherwin (1994). How We Die: Reflections on Life's Final Chapter. New York: Knopf Random House. ISBN 0679414614.

- ^ Nuland, Sherwin (February 2005). "Do You Want to Live Forever?". Technology Review.

- ^ a b Nuland, Sherwin (February 2005). "Do You Want to Live Forever?". Technology Review. Page 7.

- ^ Pontin, Jason (February 2005). "Against Transcendence", Technology Review.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey (April 2005). "Aubrey de Grey Responds", Technology Review.

- ^ TR Readers (April 2005). "LETTERS: Our February cover story on Aubrey de Grey and antiaging science lives on". Technology Review.

- ^ Pontin, Jason (July 28, 2005). "The SENS Challenge". Technology Review.

- ^ Pontin, Jason (March 14, 2006). "We've picked the judges for our biogerontology prize". Technology Review.

- ^ "SENS Withstands Three Challenges : $20,000 Remains Unclaimed". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ a b Aubrey D.N.J, de Grey (2007). "Life Span Extension Research and Public Debate: Societal Considerations" (PDF). Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology 1 (1, Article 5). doi:10.2202/1941-6008.1011. http://www.mfoundation.org/files/sens/ENHANCE-PP.pdf. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ a b Olshansky, S. Jay; Perry, Daniel; Miller, Richard A.; Butler, Robert N. (March 2006). "In Pursuit of the Longevity Dividend: What Should We Be Doing To Prepare for the Unprecedented Aging of Humanity?". The Scientist. 20 (3): 28–36.

- ^ "Conferences". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 17, 2008.

- ^ "SENS roundtable 1: Biotechnological foreseeability of ENS (October 1, 2000)". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ "SENS roundtable 4: Enhancing lysosomal catabolic function using microbial enzymes (July 26, 2004)". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ "Program". Edmonton Aging Symposium. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ "Presentation Archive". Edmonton Aging Symposium. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ "Understanding Aging". Methuselah Foundation. 2008. http://www.mfoundation.org/UABBA/. Retrieved 2009-03-02.[dead link]

- ^ "The International Association of Biomedical Gerontology 10th Congress (September 19–23, 2003)". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ de Grey, Aubrey, Ed. (June 2004). "Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence: Why Genuine Control of Aging May Be Foreseeable". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1019: xv–xvi; 1–592. PMID 15320311.

- ^ "Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS), Second Conference (September 7–11, 2005)". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ "Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS), Third Conference (September 6–10, 2007)". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 1, 2008.

- ^ "Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence (SENS), Fourth Conference". SENS4 — Cambridge. Methuselah Foundation. 2008. http://www.mfoundation.org/sens4. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ^ "Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence: Covering the SENS4 conference". Research in the biology of aging. Ouroboros. September 3, 2009. http://ouroboros.wordpress.com/2009/09/03/sens4-coverage/. Retrieved 2009-09-09.

- ^ "SENS 4 Video Gallery"

- ^ "Conferences". SENS4 — Cambridge. SENS Foundation. 2010. http://www.sens.org/conferences. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ^ "What is the Methuselah Foundation?". Methuselah Foundation. Retrieved on July 5, 2008.

Bibliography

- de Grey, Aubrey; Rae, Michael (September 2007). Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs that Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 416 pp. ISBN 0312367066.

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.