- Equisetum

-

"Horsetail" redirects here. For other uses, see Horse tail (disambiguation).

Equisetaceae

Temporal range: Late Mesozoic [1] to Recent

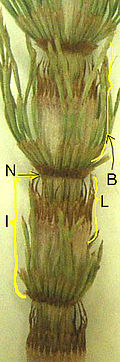

"Candocks" of the Great Horsetail (Equisetum telmateia telmateia), showing whorls of branches and the tiny dark-tipped leaves Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae Division: Pteridophyta Class: Equisetopsida Order: Equisetales Family: Equisetaceae Genus: Equisetum

L.Species see text

Equisetum (

/ˌɛkwɨˈsiːtəm/; horsetail, snake grass, puzzlegrass) is the only living genus in the Equisetaceae, a family of vascular plants that reproduce by spores rather than seeds.[2]

/ˌɛkwɨˈsiːtəm/; horsetail, snake grass, puzzlegrass) is the only living genus in the Equisetaceae, a family of vascular plants that reproduce by spores rather than seeds.[2]Equisetum is a "living fossil", as it is the only living genus of the entire class Equisetopsida, which for over one hundred million years was much more diverse and dominated the understory of late Paleozoic forests. Some Equisetopsida were large trees reaching to 30 meters tall;[3] the genus Calamites of family Calamitaceae for example is abundant in coal deposits from the Carboniferous period.

A superficially similar but entirely unrelated flowering plant genus, mare's tail (Hippuris), is occasionally misidentified and misnamed as "horsetail".

It has been suggested that the pattern of spacing of nodes in horsetails, wherein those toward the apex of the shoot are increasingly close together, inspired Napier to discover logarithms.[4]

Contents

Etymology

Microscopic view of Rough Horsetail, Equisetum hyemale (2-1-0-1-2 is one millimeter with 1/20th graduation).

Microscopic view of Rough Horsetail, Equisetum hyemale (2-1-0-1-2 is one millimeter with 1/20th graduation).

The small white protuberances are accumulated silicates on cells.The name "horsetail", often used for the entire group, arose because the branched species somewhat resemble a horse's tail. Similarly, the scientific name Equisetum derives from the Latin equus ("horse") + seta ("bristle").

Other names include candock for branching individuals, and scouring-rush for unbranched or sparsely branched individuals. The latter name refers to the plants' rush-like appearance, and to the fact that the stems are coated with abrasive silicates, making them useful for scouring (cleaning) metal items such as cooking pots or drinking mugs, particularly those made of tin. In German, the corresponding name is Zinnkraut ("tin-herb"). Rough horsetail E. hyemale is still boiled and then dried in Japan, to be used for the final polishing process on woodcraft to produce a smoother finish than any sandpaper.

Distribution, ecology and uses

The genus Equisetum is near-cosmopolitan, being absent only from Antarctica. They are perennial plants, either herbaceous and dying back in winter as most temperate species, or evergreen as most tropical species and the temperate species rough horsetail (E. hyemale), branched horsetail (E. ramosissimum), dwarf horsetail (E. scirpoides) and variegated horsetail (E. variegatum). They mostly grow 0.2-1.5 m tall, though the "giant horsetails" are recorded to grow as high as 2.5 m (northern giant horsetail, E. telmateia), 5 m (southern giant horsetail, E. giganteum) or 8 m (Mexican giant horsetail, E. myriochaetum), and allegedly even more.[5]

Many plants in this genus prefer wet sandy soils, though some are semi-aquatic and others are adapted to wet clay soils. The stalks arise from rhizomes that are deep underground and almost impossible to dig out. The field horsetail (E. arvense) can be a nuisance weed, readily regrowing from the rhizome after being pulled out. It is also unaffected by many herbicides designed to kill seed plants. However, as E. arvense prefers an acid soil, lime may be used to assist in eradication efforts to bring the soil pH to 7 or 8.[6] Members of the genus have been declared noxious weeds in Australia and in the US state of Oregon.[7][8]

If eaten in large quantities, the foliage of some species is poisonous to grazing animals, including (somewhat ironically given its common name) being poisonous to horses.[9] On the other hand, the young fertile stems bearing strobili of some species are cooked and eaten by humans in Japan, although considerable preparation is required and care should be taken.[10] The dish is similar to asparagus and is called tsukushi.[11] The people of ancient Rome would also eat meadow horsetail in this manner, but they also used it to make tea as well as a thickening powder.[12] Indians of the North American Pacific Northwest eat the young shoots of this plant raw.[13] The leaves are used as a dye and give a soft green colour. An extract is often used to provide silica for supplementation. Horsetail was often used by Indians to polish wooden tools. Equisetum species are often used to analyze gold concentrations in an area due to their voracious ability to take up the metal when it is in a solution.[12]

Anatomy

In these plants the leaves are greatly reduced and usually non-photosynthetic. They contain a single, non-branching vascular trace, which is the defining feature of microphylls. However, it has recently been recognised that horsetail microphylls are probably not primitive like in Lycopodiophyta (clubmosses and relatives), but rather advanced adaptations, evolved by the reduction of a megaphyll.[14] They are therefore sometimes actually referred to as megaphylls to reflect this homology.

The leaves of horsetails grow in whorls fused into nodal sheaths. The stems are green and photosynthetic, and distinctive in being hollow, jointed and ridged (with sometimes 3 but usually 6-40 ridges) and these are often played with by children who will separate and then seamlessly rejoin the segments. There may or may not be whorls of branches at the nodes; when present, these branches are identical to the main stem except being smaller and more delicate.

Spores

The spores are borne under sporangiophores in strobili, cone-like structures at the tips of some of the stems. In many species the cone-bearing stems are unbranched, and in some (e.g. field horsetail, E. arvense) they are non-photosynthetic, produced early in spring separately from photosynthetic sterile stems. In some other species (e.g. marsh horsetail, E. palustre) they are very similar to sterile stems, photosynthetic and with whorls of branches.

Horsetails are mostly homosporous, though in the field horsetail smaller spores give rise to male prothalli. The spores have four elaters that act as moisture-sensitive springs, assisting spore dispersal after the sporangia have split open longitudinally.

Systematics

Species

The living members of the genus Equisetum are divided into two distinct lineages, which are treated as subgenera. Hybridogenic species are common, but such hybridization has only been recorded between members of the same subgenus.[15]

In addition, there are numerous ill-determined populations. One of them, the Kamchatka Horsetail ("Equisetum camtschatcense"[verification needed]), is an ornamental forming imposing stands of these archaic plants.

- Subgenus Equisetum

- Equisetum arvense L. - Field Horsetail, Common Horsetail or "giant horsetail"

- Equisetum bogotense Kunth - Andean Horsetail or "giant horsetail"

- Equisetum diffusum L. - Himalayan Horsetail

- Equisetum fluviatile L. - Water Horsetail

- Equisetum palustre L. - Marsh Horsetail

- Equisetum pratense Ehrh. - Meadow Horsetail, Shade Horsetail, Shady Horsetail

- Equisetum sylvaticum L. - Wood Horsetail

- Equisetum telmateia Ehrh. - Great Horsetail, Northern Giant Horsetail

- Subgenus Hippochaete

- Equisetum giganteum L. - Southern Giant Horsetail or "giant horsetail"

- Equisetum myriochaetum Schlect. & Cham. - Mexican Giant Horsetail or "giant horsetail"

- Equisetum hyemale L. - Rough Horsetail, Scouringrush Horsetail

- Equisetum laevigatum A. Braun - Smooth Horsetail

- Equisetum ramosissimum Desf. - Branched Horsetail

- Equisetum scirpoides Michx. - Dwarf Horsetail

- Equisetum variegatum Schleich. ex Weber & Mohr - Variegated Horsetail

Named hybrids

- Hybrids between species in subgenus Equisetum

- Equisetum × bowmanii C.N.Page (Equisetum sylvaticum × Equisetum telmateia)

- Equisetum × dycei C.N.Page (Equisetum fluviatile × Equisetum palustre)

- Equisetum × font-queri Rothm. (Equisetum palustre × Equisetum telmateia)

- Equisetum × litorale Kühlew ex Rupr. (Equisetum arvense × Equisetum fluviatile)

- Equisetum × mchaffieae C.N. Page (Equisetum fluviatile × Equisetum pratense)

- Equisetum × mildeanum Rothm. (Equisetum pratense × Equisetum sylvaticum)

- Equisetum × robertsii Dines (Equisetum arvense × Equisetum telmateia)

- Equisetum × rothmaleri C.N.Page (Equisetum arvense × Equisetum palustre)

- Equisetum × willmotii C.N.Page (Equisetum fluviatile × Equisetum telmateia)

- Hybrids between species in subgenus Hippochaete

- Equisetum × ferrissii Clute (Equisetum hyemale × Equisetum laevigatum)

- Equisetum × moorei Newman (Equisetum hyemale × Equisetum ramosissimum)

- Equisetum × nelsonii (A.A.Eat.) Schaffn. (Equisetum laevigatum × Equisetum variegatum)

- Equisetum × schaffneri Milde (Equisetum giganteum × Equisetum myriochaetum)

- Equisetum × trachydon A.Braun (Equisetum hyemale × Equisetum variegatum)

Equisetum cell walls

The crude cell extracts of all Equisetum species tested contain mixed-linkage glucan : xyloglucan endotransglucosylase (MXE) activity.[16] This is a novel enzyme and is not known to occur in any other plants. In addition, the cell walls of all Equisetum species tested contain mixed-linkage glucan (MLG), a polysaccharide which, until recently, was thought to be confined to the Poales.[17][18] The evolutionary distance between Equisetum and the Poales suggests that each evolved MLG independently. The presence of MXE activity in Equisetum suggests that they have evolved MLG along with some mechanism of cell wall modification. The lack of MXE in the Poales suggests that there it must play some other, currently unknown, role. Due to the correlation between MXE activity and cell age, MXE has been proposed to promote the cessation of cell expansion.

Medicinal uses

The plant has a long history of medicinal uses, although modern sources include cautions with regard to its use.[19] The European Food Safety Authority issued a report assessing its medicinal uses in 2009.[20] Research has confirmed its action as an anti-oxidant.[21]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Journal reference: American Journal of Botany, DOI: 10.3732/ajb.1000211". http://www.amjbot.org/cgi/content/abstract/98/4/680.

- ^ Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- ^ "An Introduction to the Genus Equisetum and the Class Sphenopsida as a whole". Florida International University. http://www.fiu.edu/~chusb001/GiantEquisetum/Intro_Equisetum.html. Retrieved 2009-07-22.

- ^ Sacks, Oliver (August 2011). "Field Trip: Hunting Horsetails". The New Yorker.

- ^ Husby (2003)

- ^ Kress, Henriette, Getting rid of horsetail, Henriette's Herbal Homepage, April 7th, 2005. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ William Thomas Parsons, Eric George Cuthbertson (2001). Noxious weeds of Australia. Csiro Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 9780643065147. http://books.google.com/?id=sRCrNAQQrpwC&pg=PA14&dq=Equisetum+australia&q=Equisetum%20australia.

- ^ "Equisetum telmateia Ehrh. giant horsetail". USDA. http://plants.usda.gov/java/profile?symbol=EQTE. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ Israelsen et al. (2006)

- ^ Plants For A Future: Equisetum arvense.

- ^ Michael Ashkenazi, Jeanne Jacob. 2003. Food culture in Japan. Greenwood Publishing Group. 232 p.

- ^ a b Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast: Washington, Oregon, British Columbia & Alaska, Written by Paul Alaback, ISBN 978-1-55105-530-5

- ^ Erna Gunther. 1973. Ethnobotany of western Washington: The knowledge and use of indigenous plants by Native Americans.

- ^ Rutishauser (1999)

- ^ Pigott (2001)

- ^ http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/120123725/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0

- ^ Fry, Stephen C.; Nesselrode, Bertram H. W. A.; Miller, Janice G.; Mewburn, Ben R. (2008). "Mixed-linkage (1→3,1→4)-β-d-glucan is a major hemicellulose of Equisetum (horsetail) cell walls". New Phytologist 179 (1): 104–15. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02435.x. PMID 18393951.

- ^ Sørensen, Iben; Pettolino, Filomena A.; Wilson, Sarah M.; Doblin, Monika S.; Johansen, Bo; Bacic, Antony; Willats, William G. T. (2008). "Mixed-linkage (1→3),(1→4)-β-d-glucan is not unique to the Poales and is an abundant component of Equisetum arvense cell walls". The Plant Journal 54 (3): 510–21. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03453.x. PMID 18284587.

- ^ "Horsetail". University of Maryland. http://www.umm.edu/altmed/articles/horsetail-000257.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ "Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to Equisetum arvense L. and invigoration of the body (ID 2437), maintenance of skin (ID 2438), maintenance of hair (ID 2438), maintenance of bone (ID 2439), and maintenance or achievement of a normal body weight (ID 2783) pursuant to Article 13 of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006". European Food Safety Authority. http://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/scdocs/scdoc/1289.htm. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- ^ "Exploring Equisetum arvense L., Equisetum ramosissimum L. and Equisetum telmateia L. as sources of natural antioxidants". Phytotherapy Research - Ministry of Science and Environmental Protection of the Republic of Serbia via John Wiley & Sons. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/121543728/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0. Retrieved 2010-05-18. "The ESR signal of DMPO-OH radical adducts in the presence of Equisetum telmateia phosphate buffer (pH 7) extract was reduced by 98.9% indicating that Equisetum telmateia could be a useful source of antioxidants with huge scavenging ability."

References

- Husby, Chad E. (2003): How large are the giant horsetails? Version of 2003-MAR-19. Retrieved 2008-NOV-20.

- Israelsen, Clark E.; McKendrick, Scott S. & Bagley, Clell V. (2006): Poisonous Plants and Equine. PDF fulltext

- Pigott, Anthony (2001): National Collection of Equisetum – Summary of Equisetum Taxonomy. Version of 2001-OCT-04. Retrieved 2008-NOV-20.

- Walkowiak, Radoslaw (2008): IEA – Equisetum Taxonomy. Version of 2008-OCT-04. Retrieved 2011-NOV-07.

- Pryer, K.M.; Schuettpelz, E.; Wolf, P.G.; Schneider, H.; Smith, A.R. & Cranfill, R. (2004): Phylogeny and evolution of ferns (monilophytes) with a focus on the early leptosporangiate divergences. Am. J. Bot. 91(10): 1582-1598. PDF fulltext

- Rutishauser, Rolf (1999): Polymerous Leaf Whorls in Vascular Plants: Developmental Morphology and Fuzziness of Organ Identities. International Journal of Plant Sciences 160(Supplement 6): 81–103. doi:10.1086/314221 PDF fulltext

- Smith, Alan R.; Pryer, Kathleen M.; Schuettpelz, Eric; Korall, Petra; Schneider, Harald & Wolf, Paul G. (2006): A classification for extant ferns. Taxon 55(3): 705-731. doi:10.1086/314221 PDF fulltext

- Weber, Reinhard (2005): Equisetites aequecaliginosus sp. nov., ein Riesenschachtelhalm aus der spättriassischen Formation Santa Clara, Sonora, Mexiko [Equisetites aequecaliginosus sp. nov., a tall horsetail from the Late Triassic Santa Clara Formation, Sonora, Mexico]. Revue de Paléobiologie 24(1): 331-364 [German with English abstract]. PDf fulltext

External links

Categories:- Equisetum

- Living fossils

- Flora of Europe

- Flora of Africa

- Flora of Asia

- Flora of North America

- Flora of South America

- Flora of Australasia

- Invasive plant species

- Invasive plant species in the United States

- Invasive plant species in California

- Invasive plant species in New Zealand

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.