- Falaise pocket

-

Coordinates: 48°53′34″N 0°11′31″W / 48.89278°N 0.19194°W

Falaise Pocket Part of Operation Overlord, Battle of Normandy

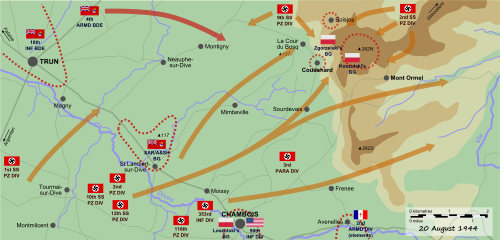

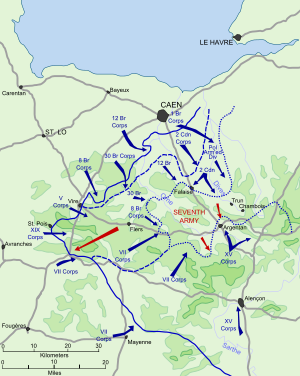

Map showing the course of the battle from 8–17 August 1944; Allied attacks are shown in blue and the German Mortain offensive and subsequent counterattacks in red.Date 12–21 August 1944 Location Normandy, France Result Decisive Allied victory[1][2] Belligerents  United States

United States

United Kingdom

United Kingdom

Canada

Canada

Poland

Poland

Free French

Free French Germany

GermanyCommanders and leaders  Bernard Montgomery

Bernard Montgomery

Omar Bradley

Omar Bradley

Harry Crerar

Harry Crerar

Miles Dempsey

Miles Dempsey

Courtney Hodges

Courtney Hodges

George Patton

George Patton Günther von Kluge

Günther von Kluge

Walter Model

Walter Model

Paul Hausser

Paul Hausser

Heinrich Eberbach

Heinrich EberbachStrength up to 17 divisions[nb 1] 14[4][5]–15 divisions[6]

Up to 100,000 men[nb 2]Casualties and losses Total casualties unavailable but significant[nb 3] ~60,000 casualties[nb 4] The battle of the Falaise Pocket, fought during the Second World War from 12 to 21 August 1944, was the decisive engagement of the Battle of Normandy. Taking its name from the pocket around the town of Falaise within which Army Group B, consisting of the German Seventh Army and the Fifth Panzer Army became encircled by the advancing Western Allies, the battle is also referred to as the battle of the Falaise Gap after the corridor which the Germans sought to maintain to allow their escape.[nb 5] The battle resulted in the destruction of the bulk of Germany's forces west of the River Seine and opened the way to Paris and the German border.

Following Operation Cobra, the American breakout from the Normandy beachhead, rapid advances were made to the south and southeast by Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr.'s U.S. Third Army. Despite lacking the resources to cope with both the U.S. penetration and simultaneous British and Canadian offensives around Caen, Field Marshal Günther von Kluge —- in overall command of Army Group B on the Western Front —- was not permitted by the Fuhrer, Adolf Hitler, to withdraw. Instead, he was ordered to counterattack the Americans around Mortain. The remnants of four panzer divisions —- which was all that von Kluge could scrape together —- were not strong enough to make any impression on the U.S. First Army, and Operation Lüttich was a disaster that merely served to drive the Germans deeper into the Allied lines, leaving them in a very dangerous position.

Seizing the opportunity to envelop von Kluge's entire force, on 8 August the Allied ground forces commander General Bernard Law Montgomery ordered his armies to converge on the Falaise-Chambois area. With the U.S. First Army forming part of the southern arm, the British Second Army the base, and the U.S. Third Army most the southern arm of the encirclement, the Germans fought hard to keep an escape route open, although their withdrawal did not begin until on 17 August. On 19 August, the Allies linked up in Chambois but in insufficient strength to seal the pocket. Gaps were forced in the Allied lines by desperate German assaults, the most significant and hard-fought being a corridor past elements of the Polish 1st Armoured Division, who had established a commanding position in the mouth of the pocket.

By the evening of 21 August, the pocket was closed for the last time, with around 50,000 Wehrmacht soldiers trapped inside. Although it is estimated that significant numbers of troops did escape, the German losses in both men and materiel were huge, and the Allies had achieved a decisive victory. Two days later Paris was liberated, and by 30 August the last German remnants had retreated across the Seine River, effectively ending Operation Overlord.

Contents

Background

Early Allied objectives in the wake of the successful Operation Overlord invasion of German-occupied France included both the deep water port of Cherbourg and the area surrounding the historic town of Caen in Normandy.[16] Attempts to rapidly expand the Allied beachhead met fierce opposition, however, and bad weather conditions in the English Channel delayed the build-up of supplies and troop reinforcements.[17][18] Cherbourg was able to hold out until 27 June, when it fell to the U.S. VII Corps,[19] and Caen resisted a number of offensives until 20 July, when it was taken by the British and Canadians during Operation Goodwood and Operation Atlantic.[20]

The Allied commander of the ground forces in Normandy General Bernard Law Montgomery —- had planned a theater strategy of drawing German forces away from the American sector to the British and Canadian sectors, thus preparing the way for a breakout by the U.S. Army.[21] On 25 July, while the Wehrmacht's attention was fixed firmly on the area around Caen, Lt. General Omar Bradley of the U.S. Army launched Operation Cobra.[22]

The U.S. First Army ruptured the thin German lines that guarded Brittany[23] and by the end of the third day, the First Army had advanced 15 mi (24 km) south from its jumping-off line in several areas.[24] On 30 July, the town of Avranches —- at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula —- was captured;[25] the Wehrmacht's left flank was now wide open, and within 24 hours Patton's U.S. VIII Corps had swept across the bridge at Pontaubault into Brittany, and then charged southwards and westwards through open country, almost without opposition.[26][27]

Operation Lüttich

The U.S. Army's advance was an extraordinarily rapid one, and by 8 August the city of Le Mans -—the former headquarters of the Wehrmacht Seventh Army —- was in American hands.[28] In the aftermath of Operation Cobra, and the simultaneous offensives of the British Army and Canadian Army, the German Army in Normandy was knocked down to such a poor condition that, as the historian Max Hastings observed, "only a few SS fanatics still entertained hopes of avoiding defeat".[29] In the east, the Soviet Union's summer offensive -— Operation Bagration —- was underway, and with this firestorm engulfing the German Army Group Centre there was no likelihood of reinforcements coming from the Eastern Front to the Western Front.[29] Instead of ordering his remaining forces in Normandy to withdraw to the Seine River, the Fuhrer sent a directive to Generalfeldmarschall Günther von Kluge's Army Group B ordering "an immediate counterattack between Mortain and Avranches"[30] to "annihilate" the enemy and to make contact with the west coast of the Cotentin Peninsula.[31]

Hitler demanded that eight of von Kluge's nine available Panzer divisions be used in the attack, but only four of them (one incomplete) could be relieved from their defensive duties and hence sent into action in time.[32] The German commanders protested that such an operation was beyond the reach of their resources[31], but these warnings were ignored and the counteroffensive, codenamed Operation Lüttich, commenced on 7 August around Mortain.[33] Initially committed to the thrust were the 2nd Panzer Division, the 1st SS Panzer Division, and the 2nd SS Panzer Division. These divisions attacked with only 75 Panzer IV tanks, 70 Panther tanks, and 32 self-propelled guns between them.[34] Forewarned through deciphered German Army radio messages, the Allies were ready and Operation Lüttich was essentially over within 24 hours, although some fighting continued until 13 August.[35][36][37] Instead of relieving the German predicament, the Mortain counterattack had driven them deeper into the Allied trap,[38] and with the most formidable of von Kluge's remaining forces now destroyed by the U.S. First Army, the entire Wehrmacht Normandy front was on the verge of collapse —- a possibility planned for by General Eisenhower.[39] General Bradley declared: "This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century. We're about to destroy an entire hostile Army and go all the way from here to the German border".[39]

Operation Totalize

A Cromwell tank and a Willys MB jeep pass an abandoned German 88 mm (3.46 in) anti-tank gun during Operation Totalize.

A Cromwell tank and a Willys MB jeep pass an abandoned German 88 mm (3.46 in) anti-tank gun during Operation Totalize.

To precipitate the German collapse and to threaten the escape route of the Wehrmacht forces fighting the British and Americans further west, the high ground north of the town of Falaise became the target of the First Canadian Army[40], commanded by General Harry Crerar and Lt. General Guy Simonds of the II Canadian Corps planned an Anglo-Canadian offensive that was codenamed Operation Totalize.[41] This operation relied on accurate preparation by heavy bombers and an innovative night attack using Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers.[42] Preceded by a large aerial bombardment by RAF Bomber Command, Operation Totalize was launched on the night of 7 August. 76 converted self-propelled gun platforms transported the lead infantry, guided by electronic means and searchlights.[41] Fighting to hold the 14 km (8.7 mi) front was Kurt Meyer's 12th SS Panzer Division, supported by tanks from the 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion and the remnants of the German 89th Infantry Division.[43] Despite initial gains on Verrières Ridge and near Cintheaux, on 9 August the momentum of this assault dwindled.[44] Strong German resistance and poor Canadian unit leadership and fighting power resulted in heavy casualties for both the 4th Canadian Armored Division and the 1st Polish Armoured Division.[45][46] By 10 August, Anglo-Canadian forces had reached Hill 195 north of Falaise, but these were unable to penetrate into the town.[46]

On the following day, Simonds pulled his battered armoured divisions out of the line and relieved them with infantry troops, ending the offensive.[47]

The Battle

Still expecting von Kluge to withdraw his forces from the tightening Allied noose, General Montgomery had for some time been planning a "long envelopment", by which the British and Canadians would pivot left from Falaise toward the River Seine, while the U.S. Third Army blocked the escape route between the Seine and Loire rivers, trapping all surviving German forces in western France.[48] However, in a telephone conversation on 8 August, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Eisenhower, commanded the execution of an American plan for a shorter envelopment centred around Argentan. Although Montgomery acknowledged the possibilities, both he and Lt. General Patton had some misgivings. If the Allies did not take Argentan, Alençon, and Falaise quickly, a large proportion of von Kluge's force might escape. Believing that he could fall back on his personal original plan if necessary, Montgomery followed General Eisenhower's orders for his plan to be carried out.[48]

Initial thrust

Patton's Third Army —- moving up from the southwest to form one arm of the encirclement —- made good initial progress. On 12 August, Alençon was captured, and despite Field Marshal von Kluge's commitment of a force he had been trying to gather for a counterattack, the next day the U.S. Fifth Armored Division of Major General Wade H. Haislip's XV Corps (in the Third Army) advanced 35 mi (56 km) and then established itself around Argentan, although this town itself remained in German hands, temporarily.[49] Concerned that the American armored forces might cause casualties by friendly fire if they ran head-on into the British Army troops advancing from the northwest, on 13 August 1944, General Bradley overrode Patton's orders for a further push north towards Falaise from Argentan using the rapidly-advancing U.S. 5th Armored Division.[49] Bradley's order specified that General Haislip's XV Corps cease its advance and "concentrate for operations in another direction".[50][nb 6] Any American troops in the vicinity of Argentan were ordered to be withdrawn, bringing to an end the pincer movement by Haislip's corps.[51] Although Patton vehemently protested the order he obeyed, leaving an exit—a "trap with a gap"—for the remaining German forces.[51] Bradley later received much of the blame for failing to exploit this early opportunity to complete the envelopment of German Army Group B,[49][nb 7] although at least one historian has claimed that the order originated with Montgomery.[52]

With the Americans on the southern flank halted (and now heavily engaged with Panzer Group Eberbach) and the British pressing in from the northwest, it fell to the Canadian First Army, incorporating the Polish 1st Armoured Division, to close the trap.[53] But for a limited operation by the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division down the Laize valley on 12 – 13 August, most of the days following "Totalize" were spent preparing a major set-piece attack on Falaise, codenamed Operation Tractable.[45] Tractable commenced at 11:42 on the morning of 14 August, covered by an artillery-delivered smokescreen that mimicked the darkness of Operation Totalize.[45][54] A series of attacks by the 4th Canadian and 1st Polish Armoured Divisions forced a passage over the Laison River, but limited access to the crossing points over the Dives River facilitated counterattacks by the German SS Heavy Panzer Battalion 102.[54] Mainly due to navigation difficulties and poor coordination between the ground and air forces,[nb 8] the first day's progress was slower than expected.[56]

On 15 August, the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions —- with the support of the 2nd Canadian (Armoured) Brigade -— renewed their drive south,[57] but progress remained slow.[56] The 4th Armoured Division captured Soulangy after harsh fighting and having weathered several German counter-attacks, although strong German resistance prevented an outright breakthrough to Trun and the day's gains were minimal.[58] The following day, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division broke into Falaise, encountering minor opposition from Waffen SS units and scattered pockets of German infantry, and by 17 August had secured the town.[59]

At midday on the 16 August, von Kluge had declined Hitler's demand for another counterattack, declaring it was utterly impossible.[56] A withdrawal was at last authorized later that afternoon, but believing von Kluge intended to surrender to the Allies,[60] on the evening of 17 August Hitler relieved him of command and recalled him to Germany. Von Kluge committed suicide en route.[61] He was succeeded by Field Marshal Walter Model, whose first act was to order the immediate retreat of the Seventh Army and the Fifth Panzer Army, while the II SS Panzer Corps' (composed of the remnants of four armored divisions) held the northern edge of the escape route against the British and Canadians, and the XLVII Panzer Corps (the remnants of two armored divisions) held the southern edge against the Americans.[61]

Closing the gap

For the Allies, time was the critical factor in blocking the German army's escape, but with the Americans held at Argentan and the Canadian advance towards Trun proceeding slowly, by 17 August the encirclement was incomplete.[61] General Stanisław Maczek's Polish 1st Armoured Division, part of the First Canadian Army, was broken into three battlegroups and ordered to make a wide sweep to the southeast to join up with the Americans at Chambois.[61] Trun fell to the Canadian 4th Armoured Division on 18 August.[62] Having captured Champeaux, on 19 August the Polish battlegroups converged on Chambois and, reinforced by the 4th Armoured, by evening the Poles had secured the town and linked up with the U.S. 90th and French 2nd Armoured Divisions.[6][63][64] The arms of the encirclement were in contact but the Allies were not yet astride Seventh Army's escape route in any great strength, and their positions came under frenzied German assaults.[64] During the day, an armoured column from the 2nd Panzer Division broke through the Canadians in St. Lambert, taking one-half of the village and keeping a road open for six hours until it was closed again around nightfall.[6] Many Germans escaped along this route, and numerous small parties infiltrated through to the Dives during the night.[65]

Having taken Chambois, two of the Polish groups drove northeast and established themselves on part of Hill 262 (Mont Ormel ridge), spending the night of 19 August entrenching the lines of approach to their positions.[66] The following morning Field Marshal Model renewed his attempts to force open an egress, ordering elements of the 2nd Panzer Division and the 9th SS Panzer Division to attack from outside the pocket towards the Polish positions.[11] Around midday, several units of the 10th SS Panzer Division, the 12th SS Panzer Division, and the 116th Panzer Division broke through the weak Polish lines and opened up a pathway, while the 9th SS Panzer Division prevented the Canadians from intervening.[67] By midafternoon, about 10,000 German troops had passed out of the pocket.[68]

Despite being isolated and coming under further strong attacks, the Poles clung on to Hill 262, which they referred to as "The Mace". Although they lacked the fighting power to close the corridor, they were able to direct artillery fire from their vantage point onto the retreating Germans, exacting a deadly toll.[69] Exasperated by the losses to his men, Colonel-General Paul Hausser —- commanding the Seventh Army —- ordered that the Polish positions be "eliminated".[68] Substantial forces -—including the remnants of the 352nd Infantry Division and several groups from the 2nd SS Panzer Division —- inflicted heavy casualties on both the 8th and 9th Battalions of the Polish 1st Armoured Division, but this assault was eventually beaten off. Their stand cost the Poles almost all of their ammunition, and it left them in a precarious position[69]. Lacking the means to intervene, they were forced to watch as the remnants of the XLVII Panzer Corps escaped from the pocket. After the brutality of the day's combat, nightfall was welcomed by both sides. With contact being avoided, fighting during the night was sporadic, although the Poles continued to call down artillery barrages to disrupt the German retreat from the sector.[69]

The German attacks resumed in the next morning. Although the Poles suffered from further casualties, and some of them were taken prisoner, the Poles retained their foothold on the ridge. At approximately 1100 hours, a final attack on the positions of the 9th Battalion was launched by nearby remnants of the SS brigades, but this was defeated at close quarters.[70] Soon after midday, the Canadian Grenadier Guards reached Mont Ormel's defenders,[58] and by late afternoon, the remainder of the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions had begun their retreat to the Seine River.[71]

The Polish losses on the Mont Ormel ridge have been stated to be 351 killed and wounded, with 11 tanks lost.[70] For the entire operation to close the Falaise pocket, the 1st Polish Armoured Division's operational report states 1,441 casualties including 466 killed in action.[72] German losses in their assaults on the ridge have been estimated at about 500 dead, with 1,000 more taken prisoner, mostly from the 12th SS Panzer Division. In addition, "scores" of Tiger, Panther, and Panzer IV tanks were destroyed, and also a significant number of artillery pieces.[70]

By evening of 21 August, the tanks of the Canadian 4th Armoured Division had linked-up with Polish forces at Coudehard, while the Canadian 3rd and 4th Infantry Divisions had secured St. Lambert and the northern passage to Chambois. The Falaise pocket had been sealed off at last.[73] Around 20,000 to 50,000 German troops (minus all of their heavy equipment) escaped through the Falaise Gap, avoiding encirclement and almost certain destruction or surrender. These troops were next reorganized and rearmed over the next half year in time to slow the Allied advances into the Netherlands and Germany.[51]

Aftermath

By 22 August, all German forces west of the Allied lines were dead or in captivity.[1] Historians differ in their estimates of German losses in the pocket. The majority of them state that between 80,000 and 100,000 troops were caught in the encirclement of which 10,000 to 15,000 were killed, 40,000 to 50,000 were taken prisoner, and 20,000 to 50,000 escaped.[nb 9] In the northern sector alone, German material losses included 344 tanks, self-propelled guns, and other light armoured vehicles[78] as well as 2,447 soft-skinned vehicles and 252 guns abandoned or destroyed.[73] In the fighting around Hill 262, German losses totalled 2,000 killed and 5,000 taken prisoner, and also 55 tanks, 44 artillery guns, and 152 other armored vehicles.[10] The once-powerful 12th SS Panzer Division lost 94 percent of its armor, nearly all of its artillery, and 70 percent of its vehicles. Mustering close to 20,000 men and 150 tanks before the Normandy campaign, after Falaise it was reduced to 300 men and 10 tanks.[71] Although elements of several German unitss had escaped to the east, even these had left behind most of their equipment.[79] After the battle, Allied investigators estimated that the Germans lost around 500 tanks and assault guns in the Falaise pocket, and very little of the equipment that was extricated survived the general retreat across the Seine River.[13]

The area in which the pocket had formed was full of the remains of battle.[80] Whole villages had been destroyed and ruined, and abandoned equipment made some roads totally impassable. Corpses littered the area —- not just those of soldiers, but also French civilians and tens of thousands of dead cattle and horses.[81] In the hot August weather, maggots crawled over the bodies, and hordes of flies descended on the area.[81][82] Warplane pilots reported being able to smell the stench of the battlefield hundreds of feet above it.[81] General Eisenhower recorded that:

The battlefield at Falaise was unquestionably one of the greatest "killing fields" of any of the war areas. Forty-eight hours after the closing of the gap, I was conducted through it on foot, to encounter scenes that could be described only by Dante. It was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time, stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.[83]Fear of infection from the rancid conditions led the Allies to declare the area an "unhealthy zone".[84] Clearing the area was a low priority though, and this went on until well into November 1944.[81] Many swollen bodies had to be shot to release their gasses from within them before they could be cremated[82], and bulldozers were used to clear the area of the dead animals.[81]

Disappointed that a significant portion of Seventh Army had eluded them, many in the Allied higher echelons -— particularly among the Americans -— were bitterly critical of what they perceived as General Montgomery's lack of urgency in closing the neck of the pocket.[13] Writing shortly after the war, Ralph Ingersoll -— a prominent peacetime journalist who served as a planner on Eisenhower's staff -— expressed the prevailing American view at the time:

The international army boundary arbitrarily divided the British and American battlefields just beyond Argentan, on the Falaise side of it. Patton's troops, who thought they had the mission of closing the gap, took Argentan in their stride and crossed the international boundary without stopping. Montgomery, who was still nominally in charge of all ground forces, now chose to exercise his authority and ordered Patton back to his side of the international boundary line. … For ten days, however, the beaten but still coherently organized German Army retreated through the Falaise gap.[85]Some historians agree that the gap could have been closed earlier. Wilmot noted that despite having some British Army divisions in reserve, General Montgomery did not reinforce Simonds, and neither was the Canadian drive on Trun and Chambois as "vigorous and venturesome" as the situation demanded.[13] Hastings wrote that Montgomery -— having witnessed what he characterised as a poor performance by the Canadian Army during Operation Totalize -— should have brought up veteran British divisions to take the spearhead.[48]

However, while acknowledging that Montgomery and Crerar might have done more to motivate to their Britons and the Canadians, these historians and others such as D'Este and Blumenson dismiss it as "absurd oversimplification" Patton's postbattle claim that the U.S. Army could have prevented the German escape had General Bradley not ordered him to stop at Argentan.[86]

Wilmot stated that "contrary to contemporary reports, the Americans did not capture Argentan until 20 August, the day after the link up at Chambois".[87] The American unit that closed the gap between Argentan and Chambois, the 90th Brigade, was according to Hastings one of the least effective brigades of any army in Normandy. He speculated that the real reason that Bradley stopped Patton was not concerns regarding accidental clashes with the British Army, but an appreciation that with powerful Wehrmacht divisions and brigades still effective at that stage of the battle, the Americans lacked the means to defend a blocking position that early, and they would have suffered an "embarrassing and gratuitous setback" at the hands of the retreating German paratroopers of thed 2nd and 12th SS Panzer Divisions.[86]

The battle of the Falaise Pocket marked the closing phase of the Battle of Normandy with a decisive German defeat.[2] Hitler's personal involvement had been damaging from the first, with his insistence on hopelessly optimistic counteroffensives, his micromanagement of his generals, and his refusal to countenance a withdrawal when his armies were threatened with annihilation.[88] More than 40 German divisions were destroyed during the Battle of Normandy. No exact figures are available, but historians estimate that the battle had cost the German forces a total of around 450,000 men, of whom 240,000 were killed or wounded.[88] The Allies had achieved this blow at a cost of 209,672 casualties among the ground forces, including 36,976 killed[73] and 19,221 missing. In addition, 16,714 Allied airmen were killed or became missing in direct connection with Operation Overlord.[89] The final battle of Operation Overlord -— the Liberation of Paris —- followed on 25 August, and Operation Overlord reached its end by 30 August with the retreat of the last German unit across the Seine River.[90]

Notes

Footnotes

- ^ Terry Copp shows the following divisions based around the Falaise pocket on 16 August 1944, but does not state if they all took an active role in the battle.

First Canadian Army: 1st Polish Armoured Division, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, 4th Canadian Armoured Division.

Second British Army: British 3rd Infantry Division, 11th Armoured Division, 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division, 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division, 59th (Staffordshire) Infantry Division.

First American Army: 1st Infantry Division, 3rd Armored Division, 9th Infantry Division, 28th Infantry Division, 30th Infantry Division.

Third American Army: 2nd French Armored Division, 90th Infantry Division.[3] - ^ Historians Carlo D'Este and Milton Shulman state that 80,000 German soldiers were caught in the Falaise pocket.[4][7] Terry Copp and Chester Wilmot claim that at least 100,000 Germans were trapped.[6][8]

- ^ The Canadians suffered around 5,500 casualties during Operations Totalize and Tractable[9] while the Polish suffered 1,441 casualties; in their move against Chambois and Mont Ormel the Poles place their losses at 325 killed, 1,002 wounded, and 114 missing.[10] Before the Chambois and Ormel actions on 14–18 August they lost 263 men. This puts the total Polish casualties for Operation Tractable at 1,704 casualties, of which 588 were fatal.[11]

- ^ Around 10,000 killed and up to 50,000 captured.[2][7][12][13]

- ^ The engagement is also sometimes referred to as the Chambois pocket, the Falaise-Chambois pocket, the Argentan-Falaise pocket,[14] or the Trun-Chambois gap.[15]

- ^ Bradley was supported in his decision by General Eisenhower.[50]

- ^ German General Hans Speidel, Chief of Staff of Army Group B, stated that Army Group B would have been completely eliminated if the U.S. 5th Armored Division had been allowed to continue its advance to Falaise, sealing off German exit avenues.[51]

- ^ Some Canadian ground forces were using yellow smoke markers to identify their positions, while RAF Bomber Command was using the same colour markers to identify its targets.[55]

- ^ Shulman, Wilmot and Ellis estimate the remnants of up to 14–15 divisions were in the pocket. D'Este stated that 80,000 troops trapped of which 10,000 were killed, 50,000 captured, and 20,000 escaped.[74] Shulman stated that almost 80,000 were trapped, 10,000 to 15,000 were killed, and 45,000 were captured.[75] Wilmot stated that 100,000 were trapped, 10,000 were killed, and 50,000 were captured.[76] Williams agreed with these casualty figures but he estimated that about 100,000 German troops escaped.[2] Tamelander estimated that 50,000 were captured, of which 10,000 were killed and 40,000 taken prisoner, while perhaps another 50,000 escaped.[77]

Citations

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 306

- ^ a b c d Williams, p. 204

- ^ Copp (2003), p. 234

- ^ a b Shulman, p. 180

- ^ Ellis, p. 440

- ^ a b c d Wilmot, p. 422

- ^ a b D’Este, p. 430–431

- ^ Copp (2003), p. 233

- ^ Jarymowycz, p. 203

- ^ a b McGilvray, p. 55

- ^ a b Jarymowycz, p. 195

- ^ Reynolds, p. 89

- ^ a b c d Wilmot, p. 424

- ^ Keegan, p. 136

- ^ Ellis, p. 448

- ^ Van der Vat, p. 110

- ^ Williams, p. 114

- ^ Griess, pp. 308–310

- ^ Hastings, p. 165

- ^ Trew, p. 48

- ^ Hart, p.38

- ^ Wilmot, pp. 390–392

- ^ Hastings, p.257

- ^ Wilmot, p. 393

- ^ Williams, p. 185

- ^ Wilmot, p. 394

- ^ Hastings, p. 280

- ^ Williams, p. 194

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 277

- ^ D'Este, p. 414

- ^ a b Williams, p. 196

- ^ Wilmot, p. 401

- ^ Hastings, p. 283

- ^ Hastings, p. 285

- ^ Messenger, pp. 213–217

- ^ Bennett 1979, pp. 112–119.

- ^ Hastings, p. 286

- ^ Hastings, p. 335

- ^ a b Williams, p. 197

- ^ D'Este, p. 404

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 296

- ^ Zuehlke, p. 168

- ^ Williams, p. 198

- ^ Hastings, p. 299

- ^ a b c Hastings, p. 301

- ^ a b Bercuson, p. 230

- ^ Hastings, p. 300

- ^ a b c Hastings, p. 353

- ^ a b c Wilmot, p. 417

- ^ a b Essame, p. 168

- ^ a b c d Essame, p. 182

- ^ D'Este, p. 441

- ^ Wilmot, p. 419

- ^ a b Bercuson, p. 231

- ^ Hastings, p. 354

- ^ a b c Hastings, p. 302

- ^ Van Der Vat, p. 169

- ^ a b Bercuson, p. 232

- ^ Copp (2006), p. 104

- ^ Wilmot, p. 420

- ^ a b c d Hastings, p. 303

- ^ Zuehlke, p. 169

- ^ Jarymowycz, p. 192

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 304

- ^ Wilmot, p.423

- ^ D'Este, p. 456

- ^ Jarymowycz, p. 196

- ^ a b Van Der Vat, p. 168

- ^ a b c D'Este, p. 458

- ^ a b c McGilvray, p. 54

- ^ a b Bercuson, p. 233

- ^ Copp (2003), p. 249

- ^ a b c Hastings, p. 313

- ^ D'Este, pp. 430–431

- ^ Shulman, pp. 180, 184

- ^ Wilmot, pp. 422, 424

- ^ Tamelander, Zetterling, p. 342

- ^ Reynolds, p. 88

- ^ Hastings, p. 314

- ^ Hastings, p. 311

- ^ a b c d e Lucas & Barker, p. 158

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 312

- ^ "World War II Database: Normandy Campaign, Phase 2". http://ww2db.com/battle_spec.php?battle_id=112. Retrieved 2009-12-18.

- ^ Lucas & Barker, p. 159

- ^ Ingersoll, Ralph (1946). Top Secret. New York: Harcourt Brace. pp. 190–91.

- ^ a b Hastings, p. 369

- ^ Wilmot, p. 425

- ^ a b Williams, p. 205

- ^ Tamelander, Zetterling, p. 341.

- ^ Hastings, p. 319

References

- Bennett, Ralph (1979). Ultra in the West: The Normandy Campaign of 1944–1945. Hutchinson & Co. ISBN 0-09-139330-2.

- Bercuson, David (2004) [1996]. Maple Leaf Against the Axis. Red Deer Press. ISBN 0-88995-305-8.

- Copp, Terry (2006). Cinderella Army: The Canadians in Northwest Europe, 1944–1945. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3925-1.

- Copp, Terry (2007) [2003]. Fields of Fire: The Canadians in Normandy. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3780-0.

- D'Este, Carlo (2004) [1983]. Decision in Normandy: The Real Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-101761-9.

- Ellis, Major L.F.; with Allen R.N., Captain G.R.G. Allen; Warhurst, Lieutenant-Colonel A.E. & Robb, Air Chief-Marshal Sir James (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1962]. Butler, J.R.M. ed. Victory in the West, Volume I: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Naval & Military Press Ltd. ISBN 1-84574-058-0.

- Essame, Hubert (1988) [1973]. Patton : as military commander. New York : Da Capo. ISBN 9780585100197.

- Griess, Thomas (2002). The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean; Department of History, United States Military Academy, West Point, New York. SquareOne. ISBN 0-7570-0160-2.

- Hart, Stephen Ashley (2007) [2000]. Colossal Cracks: Montgomery's 21st Army Group in Northwest Europe, 1944–45. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3383-1.

- Hastings, Max (2006) [1985]. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy. Vintage Books USA; Reprint edition. ISBN 0-307-27571-X.

- Jarymowycz, Roman (2001). Tank Tactics; from Normandy to Lorraine. Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-950-0.

- Keegan, John (2006). Atlas of World War II. Collins. ISBN 0-06-089077-0.

- Lucas, James; Barker, James (1978). The Killing Ground, The Battle of the Falaise Gap, August 1944. BT Batsford Ltd. ISBN 0-7134-0433-7.

- McGilvray, Evan (1 Nov 2004 (1st edition)). The Black Devils' March - A Doomed Odyssey - The 1st Polish Armoured Division 1939–45. Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-874622-42-0.

- Messenger, Charles (1999). The Illustrated Book of World War II. San Diego, CA: Thunder Bay Publishing. ISBN 1-57145-217-6.

- Reynolds, Michael (2002). Sons of the Reich: The History of II SS Panzer Corps in Normandy, Arnhem, the Ardennes and on the Eastern Front. Casemate Publishers and Book Distributors. ISBN 0-9711709-3-2.

- Shulman, Milton (2007) [1947]. Defeat in the West. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-548-43948-6.

- Tamelander, Michael; Zetterling, Niklas (2003) [1995] (in Swedish). Avgörandes ögonblick: Invasionen i Normandie 1944 (New ed.). Stockholm: Nordstedts Förlag. ISBN 91-1-301204-5.

- Trew, Simon; Badsey, Stephen (2004). Battle for Caen. Battle Zone Normandy. The History Press Ltd. ISBN 0-7509-3010-1.

- Van Der Vat, Dan (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Madison Press Limited. ISBN 1-55192-586-9.

- Williams, Andrew (2004). D-Day to Berlin. Hodder. ISBN 0-340-83397-1.

- Wilmot, Chester; Christopher Daniel McDevitt (1997) [1952]. The Struggle For Europe. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

- Zuehlke, Mark (2001). The Canadian Military Atlas: Canada's Battlefields from the French and Indian Wars to Kosovo. Stoddart. ISBN 0-7737-3289-6.

External links

- Bridge, Arthur. "In the eye of the storm: A recollection of three days in the Falaise gap 19–21 August 1944". http://www.wlu.ca/lcmsds/cmh/back%20issues/CMH/volume%209/Issue%203/Bridge%20-%20In%20the%20Eye%20of%20the%20Storm%20-%20A%20Recollection%20of%20Three%20Days%20in%20the%20Falaise%20Gap,%2019-21%20August%201944.pdf.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. "Account of the Polish battle on hill 262". http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/stories/46/a2450846.shtml.

- "Canada at War: Canadians in the Falaise Gap". http://wwii.ca/page23.html.

- "Canada at War: The Battle of Hill 195". http://wwii.ca/page51.html.

- "Canada at War: The Battle at St. Lambert-Sur-dives". http://wwii.ca/page27.html.

- Richard, Duda; Steven, Duda. "Captain Kazimierz DUDA - 1st Polish Armoured Division". http://www.opusmedia.fr/kazimierzduda/default_gb.asp.

- Stacey, Colonel Charles Perry; Bond, Major C.C.J. (1960). "Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III. The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945" (PDF). The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. http://www.dnd.ca/dhh/collections/books/files/books/Victory_e.pdf. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- Wiacek, Jacques. "Closing of the Falaise Pocket". http://www.memorial-montormel.org/?id=50.

- "Film footage of the battle". http://s143.photobucket.com/albums/r134/51highland/?action=view¤t=Falaise.flv.

Categories:- Operation Overlord

- Battles of World War II involving Canada

- Battles of World War II involving France

- Battles and operations of World War II involving Poland

- Battles of World War II involving the United States

- Battles of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Military operations of World War II involving Germany

- ^ Terry Copp shows the following divisions based around the Falaise pocket on 16 August 1944, but does not state if they all took an active role in the battle.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.