- World's Columbian Exposition

-

The World's Columbian Exposition (the official shortened name for the World's Fair: Columbian Exposition,[1] also known as The Chicago World's Fair) was a World's Fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. Chicago bested New York City; Washington, D.C.; and St. Louis for the honor of hosting the fair. The fair had a profound effect on architecture, the arts, Chicago's self-image, and American industrial optimism. The Chicago Columbian Exposition was, in large part, designed by Daniel Burnham and Frederick Law Olmsted. It was the prototype of what Burnham and his colleagues thought a city should be. It was designed to follow Beaux Arts principles of design, namely French neoclassical architecture principles based on symmetry, balance, and splendor.

The exposition covered more than 600 acres (2.4 km2), featuring nearly 200 new (but purposely temporary) buildings of predominately neoclassical architecture, canals and lagoons, and people and cultures from around the world. More than 27 million people attended the exposition during its six-month run. Its scale and grandeur far exceeded the other world fairs, and it became a symbol of the emerging American Exceptionalism, much in the same way that the Great Exhibition became a symbol of the Victorian era United Kingdom.

Dedication ceremonies for the fair were held on October 21, 1892, but the fairgrounds were not actually opened to the public until May 1, 1893. The fair continued until October 30, 1893. In addition to recognizing the 400th anniversary of the discovery of the New World by Europeans, the fair also served to show the world that Chicago had risen from the ashes of the Great Chicago Fire. This had destroyed much of the city in 1871. On October 9, 1893, the day designated as Chicago Day, the fair set a record for outdoor event attendance, drawing 716,881 persons to the fair.

Many prominent civic, professional, and commercial leaders from around the United States participated in the financing, coordination, and management of the Fair, including Chicago shoe tycoon Charles Schwab, Chicago railroad and manufacturing magnate John Whitfield Bunn, and Connecticut banking, insurance, and iron products magnate Milo Barnum Richardson, among many others.[2]

The exposition was such a major event in Chicago that one of the stars on the municipal flag honors it.[3][4]

Contents

Planning and organization

The fair was planned in the early 1890s, the Gilded Age of rapid industrial growth, immigration, and class violence. World's fairs, such as London's 1851 Crystal Palace Exhibition, had been successful in Europe as a way to bring together societies fragmented along class lines. However, the first American attempt at world's fair, in 1876 in Philadelphia, lost money. Nonetheless, ideas about marking the 400th anniversary of Columbus' landing started to take hold in the 1880s. Towards the end of the decade, civic leaders in St. Louis, New York City, Washington DC and Chicago expressed interest in hosting a fair, in order to generate profits, boost real estate values, and promote their cities. Congress was called on to decide the location. New York's financiers J. P. Morgan, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and William Waldorf Astor, among others, pledged $15 million to finance the fair if Congress awarded it to New York, while Chicagoans Charles T. Yerkes, Marshall Field, Philip Armour, Gustavus Swift, and Cyrus McCormick, offered to finance a Chicago fair. What finally persuaded Congress was Chicago banker Lyman Gage who raised several million additional dollars in a 24-hour period, over and above New York's final offer. [5]

The exposition corporation and national exposition commission settled on Jackson Park as the fair site. Daniel H. Burnham was selected as director of works, and George R. Davis as director-general. Burnham emphasized architecture and sculpture as central to the fair and assembled the period's top talent to design the buildings and grounds including Frederick Law Olmsted for the grounds. The buildings were neoclassical, painted white, resulting in the name “White City” for the fair site.[5]

Meanwhile Davis's team organized the exhibits with the help of G. Brown Goode of the Smithsonian. The Midway was inspired by the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition which included ethnological "villages". The Exposition's offices set up shop in the upper floors of the Rand McNally Building on Adams Street, the world's first all-steel-framed skyscraper.[6]

Description

The fair opened in May and ran through October 30, 1893. Forty-six nations participated in the fair (it was the first world's fair to have national pavilions[7]), constructing exhibits and pavilions and naming national "delegates" (for example, Haiti selected Frederick Douglass to be its delegate).[8] The Exposition drew nearly 26 million visitors. It left a remembered vision that inspired the Emerald City of L. Frank Baum's Land of Oz and Walt Disney's theme parks. Disney's father Elias was a construction worker on some of the buildings at the fair.[9]

The exposition was located in Jackson Park and on the Midway Plaisance on 630 acres (2.5 km2) in the neighborhoods of South Shore, Jackson Park Highlands, Hyde Park and Woodlawn. Charles H. Wacker was the Director of the Fair. The layout of the fairgrounds was created by Frederick Law Olmsted, and the Beaux-Arts architecture of the buildings was under the direction of Daniel Burnham, Director of Works for the fair. Renowned local architect Henry Ives Cobb designed several buildings for the exposition. The Director of the American Academy in Rome, Francis David Millet, directed the painted mural decorations. Indeed, it was a coming-of-age for the arts and architecture of the "American Renaissance", and it showcased the burgeoning neoclassical and Beaux-Arts styles.

White City

Most of the buildings were based on classical architecture. The area at the Court of Honor was known as The White City. The buildings were made of a white stucco, which, in comparison to the tenements of Chicago, seemed illuminated. It was also called the White City because of the extensive use of street lights, which made the boulevards and buildings usable at night. It included such buildings as:

- The Administration Building, designed by Richard Morris Hunt

- The Agricultural Building, designed by Charles McKim

- The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, designed by George B. Post

- The Mines and Mining Building, designed by Solon Spencer Beman

- The Electricity Building, designed by Henry Van Brunt and Frank Maynard Howe

- The Machinery Building, designed by Robert Swain Peabody of Peabody and Stearns

- The Woman's Building, designed by Sophia Hayden

Louis Sullivan's polychrome proto-Modern Transportation Building was an outstanding exception to the prevailing style, as he tried to develop an organic American form. He believed that the classical style of the White City had set back modern American architecture by forty years.

As detailed in Erik Larson's popular history The Devil in the White City, extraordinary effort was required to accomplish the exposition, and much of it was unfinished on opening day. The famous Ferris Wheel, which proved to be a major attendance draw and helped save the fair from bankruptcy, was not finished until June, because of waffling by the board of directors the previous year on whether to build it. Frequent debates and disagreements among the developers of the fair added many delays. The spurning of Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show proved a serious financial mistake. Buffalo Bill set up his highly popular show next door to the fair and brought in a great deal of revenue that he did not have to share with the developers. Nonetheless, construction and operation of the fair proved to be a windfall for Chicago workers during the serious economic recession that was sweeping the country.[citation needed]

Early in July, a Wellesley College English teacher named Katharine Lee Bates visited the fair. The White City later inspired the reference to "alabaster cities" in her poem "America the Beautiful".[10]

The fair ended with the city in shock, as popular mayor Carter Harrison, Sr. was assassinated by Patrick Eugene Prendergast two days before the fair's closing. Closing ceremonies were canceled in favor of a public memorial service. Jackson Park was returned to its status as a public park, in much better shape than its original swampy form. The lagoon was reshaped to give it a more natural appearance, except for the straight-line northern end where it still laps up against the steps on the south side of the Palace of Fine Arts/Museum of Science & Industry building. The Midway Plaisance, a park-like boulevard which extends west from Jackson Park, once formed the southern boundary of the University of Chicago, which was being built as the fair was closing. (The university has since developed south of the Midway.) The university's football team, the Maroons, were the original "Monsters of the Midway". The exposition is mentioned in the university's alma mater: "The City White hath fled the earth,/But where the azure waters lie,/A nobler city hath its birth,/The City Gray that ne'er shall die."

Almost all of the fair's structures were designed to be temporary; of the more than 200 buildings erected for the fair, the only two which still stand in place are the Palace of Fine Arts and the World's Congress Auxiliary Building. From the time the fair closed until 1920, the Palace of Fine Arts housed the Field Columbian Museum (now the Field Museum of Natural History, since relocated). In 1933, the Palace building re-opened as the Museum of Science and Industry.[11] The second building, the World's Congress Building, was one of the few buildings not built in Jackson Park, instead it was built downtown in Grant Park. The cost of construction of the World's Congress Building was shared with the Art Institute of Chicago, which, as planned, moved into the building (the museum's current home) after the close of the fair.

Three other significant buildings survived the fair. The first is the Norway pavilion, a building preserved at a museum called Little Norway in Blue Mounds, Wisconsin. The second is the Maine State Building, designed by Charles Sumner Frost, which was purchased by the Ricker family of Poland Spring, Maine. They moved the building to their resort to serve as a library and art gallery. The Poland Spring Preservation Society now owns the building, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. The third is the Dutch House, which was moved to Brookline, Massachusetts. The main altar at St. John Cantius in Chicago, as well as its matching two side altars, are reputed to be from the Columbian Exposition. The other buildings at the fair were intended to be temporary. Their facades were made not of stone, but of a mixture of plaster, cement and jute fiber called staff, which was painted white, giving the buildings their "gleam". Architecture critics derided the structures as "decorated sheds". The White City, however, so impressed everyone who saw it (at least before air pollution began to darken the façades) that plans were considered to refinish the exteriors in marble or some other material. In any case, these plans were abandoned in July 1894 when much of the fair grounds was destroyed in a fire. (The fire occurred at the height of the Pullman Strike.)

The exposition was extensively reported by Chicago publisher William D. Boyce's reporters and artists.[12] There is a very detailed and vivid description of all facets of this fair by the Persian traveler Mirza Mohammad Ali Mo'in ol-Saltaneh written in Persian. He departed from Persia on April 20, 1892, especially for the purpose of visiting the World's Columbian Exposition.[13]

The White City and The City Beautiful Movement

The White City is largely accredited for ushering in the City Beautiful movement and planting the seeds of modern city planning. The highly integrated design of the landscapes, promenades, and structures provided a vision of what is possible when planners, landscape architects, and architects work together on a comprehensive design scheme. The White City inspired cities to focus on the beautification of the components of the city in which municipal government had control; streets, municipal art, public buildings and public spaces. The designs of the City Beautiful Movement (closely tied with the municipal art movement) are identifiable by their classical architecture, plan symmetry, picturesque views, axial plans, as well as their magnificent scale. Where the municipal art movement focused on beautifying one feature in a City, the City Beautiful movement began to make improvements on the scale of the district. The White City of the World's Colombian Exposition inspired the Merchant's Club of Chicago to commission Daniel Burnham to create the Plan of Chicago in 1909, which became the first modern comprehensive city plan in America.[14]

Electricity at the fair

The International Exposition was held in a building which was devoted to electrical exhibits. General Electric Company (backed by Thomas Edison and J.P. Morgan) had proposed to power the electric exhibits with direct current originally at the cost of US$1.8 million. After this was initially rejected as exorbitant, General Electric re-bid their costs at $554,000. However, Westinghouse, armed with Nikola Tesla's alternating current system, proposed to illuminate the Columbian Exposition in Chicago for $399,000, and Westinghouse won the bid.[15] It was a historical moment and the beginning of a revolution, as Nikola Tesla and George Westinghouse introduced the public to alternating-current electrical power by illuminating the exposition. All the exhibits were from commercial enterprises. Thomas Edison, Brush, Western Electric, and Westinghouse had exhibits. The public observed firsthand the qualities and abilities of alternating current power.

Tesla's high-frequency high-voltage lighting produced more efficient light with quantitatively less heat. A two-phase induction motor was driven by current from the main generators to power the system. Edison tried to prevent the use of his light bulbs in Tesla's works. General Electric banned the use of Edison's lamps in Westinghouse's plan in retaliation for losing the bid. Westinghouse's company quickly designed a double-stopper lightbulb (sidestepping Edison's patents) and was able to light the fair. The Westinghouse lightbulb was invented by Reginald Fessenden, later to be the first person to transmit voice by radio. Fessenden replaced Edison's delicate platinum lead-in wires with an iron-nickel alloy, thus greatly reducing the cost and increasing the life of the lamp.[16]

The Westinghouse Company displayed several polyphase systems. The exhibits included a switchboard, polyphase generators, step-up transformers, transmission line, step-down transformers, commercial size induction motors and synchronous motors, and rotary direct current converters (including an operational railway motor). The working scaled system allowed the public a view of a system of polyphase power which could be transmitted over long distances, and be utilized, including the supply of direct current. Meters and other auxiliary devices were also present.

Tesla displayed his phosphorescent lighting, powered without wires by high-frequency fields, and employed a similar process, using high-voltage, high-frequency alternating current to shoot lightning from his fingertips.[citation needed] Tesla displayed the first practical phosphorescent lamps (a precursor to fluorescent lamps). Tesla's lighting inventions exposed to high-frequency currents would bring the gases to incandescence.[citation needed]

Also at the Fair, the Chicago Athletic Association Football team played one of the very first night football games against West Point (the earliest being on September 28, 1892 between Mansfield State Normal and Wyoming Seminary). Chicago won the game 14-0. The game lasted only 40 minutes, compared to the normal 90 minutes.[17]

Attractions

The World's Columbian Exposition was the first world's fair with an area for amusements that was strictly separated from the exhibition halls. This area, developed by a young music promoter, Sol Bloom, concentrated on Midway Plaisance and introduced the term "midway" to American English to describe the area of a carnival or fair where sideshows are located.

It included carnival rides, among them the original Ferris Wheel, built by George Ferris. This wheel was 264 feet (80 m) high and had 36 cars, each of which could accommodate 60 people. The importance of the Columbian Exposition is highlighted by the use of "Rueda de Chicago" (Chicago Wheel) in many Latin American countries such as Costa Rica and Chile in reference to the Ferris Wheel.[citation needed]

Eadweard Muybridge gave a series of lectures on the Science of Animal Locomotion in the Zoopraxographical Hall, built specially for that purpose on Midway Plaisance. He used his zoopraxiscope to show his moving pictures to a paying public. The hall was the first commercial movie theater.[18]

The "Street in Cairo" included the popular dancer known as Little Egypt.[19] She introduced America to the suggestive version of the belly dance known as the "hootchy-kootchy", to a tune said to be improvised by Sol Bloom (and now more commonly associated with snake charmers).[20] Bloom did not copyright the song, putting it straight into the public domain.

Black musicians at the fair

The fair featured a number of important and soon to be important figures in African-American music including and provided an early exposure to white America of various strains of black music;

- Scott Joplin ~ The young pianist and cornet player led a small band playing an early version of ragtime. Although not an official part of the expo they are believed to have played gigs on the outskirts of the fair.[21] Scott Joplin's performance at the exposition introduced ragtime to new audiences.[22] The exposition attracted attention to the Chicago ragtime scene, led by patriarch Plunk Henry and exemplified in performance at the exposition by Johnny Seymour.[23]

- W.C. Handy ~ It is often claimed that the twenty year old musician played with The Mahara Minstrels at the fair, but his autobiography states that he arrived a year early and went on to St. Louis and doesn't mention attending the fair.[24]

- Henry Thomas (blues musician) ~ A singer and guitarist later known for playing an early version of the blues, "Ragtime" Thomas was an itinerant street busker who reportedly played the fair in an unofficial capacity.

- Sissieretta Jones ~ Known as The Black Patti and an already famous opera singer.[21]

- George W. Johnson ~ A popular minstrel singer and early recording artist, although it is not known if he actually performed in person, his recordings with the Edison Gramophone would certainly have been included as part of the Edison exhibit.

- Will Marion Cook ~ Composer and orchestra leader had prepared "Scenes from the Opera of Uncle Tom's Cabin" for performance. The performance however was canceled. Cook is believed to have attended the fair on his own and may have performed informally solo.

- Classical violinist Joseph Douglass achieved wide recognition after his performance there and became the first African-American violinist to conduct a transcontinental tour and the first to tour as a concert violinist.[25][26]

- A paper on African-American spirituals and shouts by Abigail Christensen was read to attendees.[27]

There were many other black artists at the fair ranging from minstrel and early ragtime groups to more formal classical ensembles to street buskers.

Other music at the fair

- The first Indonesian music performance in the United States was at the exposition.[28]

- A group of hula dancers led to increased awareness of Hawaiian music among Americans throughout the country.[29]

- Stoughton Musical Society, the oldest choral society in the United States, presented the first concerts of early American music at the exposition.

- The first Eisteddfod (a Welsh choral competition with a history spanning many centuries) held outside of Wales was held in Chicago at the exposition.

Non musical attractions

Although denied a spot at the fair, Buffalo Bill Cody decided to come to Chicago anyway, setting up his Wild West show just outside the edge of the exposition. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner gave academic lectures reflecting on the end of the frontier which Buffalo Bill represented.

The Electrotachyscope of Ottomar Anschütz was demonstrated, which used a Geissler Tube to project the illusion of moving images. Louis Comfort Tiffany made his reputation with a stunning chapel designed and built for the Exposition. This chapel has been carefully reconstructed and restored. It can be seen in at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art.

Architect Kirtland Cutter's Idaho Building, a rustic log construction, was a popular favorite,[30] visited by an estimated 18 million people.[31] The building's design and interior furnishings were a major precursor of the Arts and Crafts movement.

The John Bull locomotive was displayed. It was only 62 years old, having been built in 1831. It was the first locomotive acquisition by the Smithsonian Institution. The locomotive ran under its own power from Washington, DC, to Chicago to participate, and returned to Washington under its own power again when the exposition closed. In 1981 it was the oldest surviving operable steam locomotive in the world when it ran under its own power again.

An original frog switch and portion of the superstructure of the famous 1826 Granite Railway in Massachusetts could be viewed. This was the first commercial railroad in the United States to evolve into a common carrier without an intervening closure. The railway brought granite stones from a rock quarry in Quincy, Massachusetts, so that the Bunker Hill Monument could be erected in Boston. The frog switch is now on public view in East Milton Square, Massachusetts, on the original right-of-way of the Granite Railway.

Norway participated by sending the Viking, a replica of the Gokstad ship. It was built in Norway and sailed across the Atlantic by 12 men, led by Captain Magnus Andersen. In 1919 this ship was moved to Lincoln Park. It was relocated in 1996 to Good Templar Park in Geneva, Illinois, where it awaits renovation.[32][33]

The 1893 Parliament of the World’s Religions, which ran from September 11 to September 27, marked the first formal gathering of representatives of Eastern and Western spiritual traditions from around the world.

The work of noted feminist author Kate McPhelim Cleary was featured during the opening of the Nebraska Day ceremonies at the fair, which included a reading of her poem "Nebraska".[34]

Visitors to the Louisiana Pavilion were each given a seeding of a cypress tree. This resulted in the spread of cypress trees to areas where they were not native. Cypress trees from those seedings can be found in many areas of West Virginia, where they flourish in the climate.[35]

Along the banks of the lake, patrons on the way to the casino were taken on a moving walkway the first of its kind open to the public,[36] called The Great Wharf, Moving Sidewalk, it allowed people to walk along or ride in seats.[1]

The German firm Krupp had a pavilion of artillery, which apparently had cost one million dollar to stage,[37] including a coastal gun of 42 cm in bore (16.54 inches) and a length of 33 calibres (45.93 feet, 14 meters). A breach loaded gun, it weighed 120.46 long tons (122.4 metric tons). According to the company's marketing: "It carried a charge projectile weighing from 2,200 to 2,500 pounds which, when driven by 900 pounds of brown powder, was claimed to be able to penetrate at 2,200 yards a wrought iron plate three feet thick if placed at right angles."[38] Nicknamed "The Thunderer", the gun had an advertised range of 15 miles; on this occasion John Schofield declared Krupps' guns "the greatest peacemakers in the world".[37] This gun was later seen as a precursor of the company's World War I Dicke Berta howitzers.[39]

Notable firsts at the fair

- Phosphorescent lamps (a precursor to fluorescent lamps)[citation needed]

- F.W. Rueckheim introduced a confection of popcorn, peanuts and molasses, it was given the name Cracker Jack in 1896.

- Congress of Mathematicians,[40] precursor to International Congress of Mathematicians

- Elongated coins

- Frederick Jackson Turner lectured on his Frontier thesis.

- Ferris Wheel

- First fully electrical kitchen including an automatic dishwasher

- John T. Shayne & Company, the local Chicago furrier helped America gain respect on the world stage of manufacturing

- Juicy Fruit gum[3]

- Quaker Oats[3]

- Cream of Wheat

- Shredded Wheat[3]

- The hamburger was introduced to the United States[citation needed]

- Milton Hershey bought a European exhibitor's chocolate manufacturing equipment and added chocolate products to his caramel manufacturing business.

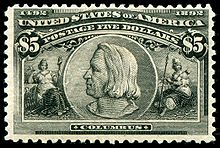

- The United States Post Office Department produced its first picture postcards and Commemorative stamp set.

- United States Mint offered its first commemorative coins: a quarter and half dollar.

- Contribution to Chicago's nickname, the "Windy City". Some argue that Charles Anderson Dana of the New York Sun coined the term related to the hype of the city's promoters. Other evidence, however, suggests the term was used as early as 1881 in relation to either Chicago's "windbag" politicians or to its weather.

- The poet and humorist Benjamin Franklin King, Jr. first performed at the exposition.

- The "clasp locker," a clumsy slide fastener and forerunner to the zipper was demonstrated by Whitcomb L. Judson.

- To hasten the painting process during construction of the fair in 1892, Francis Davis Millet invents spray painting.

- Pabst Blue Ribbon

Later years

The exposition was one influence leading to the rise of the City Beautiful movement.[41] Results included grand buildings and fountains built around Olmstedian parks, shallow pools of water on axis to central buildings, larger park systems, broad boulevards and parkways and, after the turn of the century, zoning laws and planned suburbs. Examples of the City Beautiful movement's works include the City of Chicago, the Columbia University campus, and the National Mall in Washington D.C.

After the fair closed, J.C. Rogers, a banker from Wamego, Kansas, purchased several pieces of art that had hung in the rotunda of the U.S. Government Building. He also purchased architectural elements, artifacts and buildings from the fair. He shipped his purchases to Wamego. Many of the items, including the artwork, were used to decorate his theater, now known as the Columbian Theatre.

Memorabilia saved by visitors can still be purchased. Numerous books, tokens, published photographs, and well-printed admission tickets can be found. While the higher value commemorative stamps are expensive, the lower ones are quite common. So too are the commemorative half dollars, many of which went into circulation.

When the exposition ended the Ferris Wheel was moved to Chicago's north side, next to an exclusive neighborhood. An unsuccessful Circuit Court action was filed against the owners of the wheel to have it moved. The wheel stayed there until it was moved to St. Louis for the 1904 World's Fair.[12]

Gallery

The Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, seen from the southwest.Horticultural Building, with Illinois Building in the background.A view toward the Peristyle from Machinery Hall.The Administration Building, seen from the Agricultural Building.Midway PlaisanceTicket for Chicago DayOne-third scale replica of Daniel Chester French's Republic, which stood in the great basin at the exposition, Chicago, 2004Canal Of Venice During Chicago World's Fair 1893A train of the Intramural RailwaySee also

- Spectacle Reef Light

- Exposition Universelle (1900)

- Pan-American Exposition

- St. John Cantius in Chicago, whose main altar, as well as its matching two side altars, reputedly originate from the 1893 Columbian Exposition

- Herman Webster Mudgett

- World's Largest Cedar Bucket

- 1893: A World's Fair Mystery, an interactive fiction that recreates the Exposition in detail

- Against the Day, a novel by Thomas Pynchon

- Expo: Magic of the White City, a documentary film about the exposition

- Jimmy Corrigan, the Smartest Kid on Earth, a graphic novel by Chris Ware

- The Devil in the White City, non-fiction book about the Exposition

- Wonder of the Worlds, an adventure novel by Sesh Heri

- Benjamin W. Kilburn, stereoscopic view concession and subsequent views

Notes

- ^ a b Truman, Benjamin (1893). History of the World's Fair: Being a Complete and Authentic Description of the Columbian Exposition From Its Inception. Philadelphia, PA: J. W. Keller & Co..

- ^ Moses Purnell Handy, "The Official Directory of the World's Columbian Exposition, May 1st to October 30th, 1893: A Reference Book of Exhibitors and Exhibits, and of the Officers and Members of the World's Columbian Commission Books of the Fairs" (William B. Conkey Co., 1893) P. 75 (See: http://books.google.com). See also: Memorial Volume. Joint Committee on Ceremonies, Dedicatory And Opening Ceremonies of the World's Columbian Exposition: Historical and Descriptive, A. L. Stone: Chicago, 1893. P. 306.

- ^ a b c d Zeldes, Leah A. (2010-04-06). "Remembering the World’s Columbian Exposition". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc.. http://www.diningchicago.com/blog/2010/04/06/remembering-the-worlds-columbian-exposition/. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "Municipal Flag of Chicago". Chicago Public Library. 2009. http://www.chipublib.org/cplbooksmovies/cplarchive/symbols/flag.php. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

- ^ a b "World's Columbian Exposition", Encyclopedia of Chicago

- ^ http://xroads.virginia.edu/~ma96/wce/history.html

- ^ Birgit Breugal for the EXPO2000 Hannover GmbH Hannover, the EXPO-BOOK The Official Catalogue of EXPO2000 with CDROM

- ^ Rydell, Robert W. (1987).All the World's a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, p. 53. University of Chicago. ISBN 0-226-73240-1.

- ^ Larson, Erik. (2003). The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America, p. 373. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-72560-9

- ^ "Falmouth Museums on the Green", Falmouth Historical Society

- ^ About The Museum - Museum History - Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, USA

- ^ a b Petterchak 2003, pp. 17–18

- ^ Muʿīn al-Salṭana, Muḥammad ʿAlī (Hāǧǧ Mīrzā), Safarnāma-yi Šīkāgū : ḵāṭirāt-i Muḥammad ʿAlī Muʿīn al-Salṭana bih Urūpā wa Āmrīkā : 1310 Hiǧrī-yi Qamarī / bih kūšiš-i Humāyūn Šahīdī, [Tihrān] : Intišrāt-i ʿIlmī, 1984, 1363/[1984].

- ^ Levy, John M. (2009) Contemporary Urban Planning.

- ^ Larson, Erik (2003). The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. New York, NY: Crown. ISBN 0609608444.

- ^ US Patent 453,742 dated 9 June 1891

- ^ Pruter, Robert (2005). "Chicago Lights Up Football World". LA 4 Foundation XVIII (II): 7–10. http://www.la84foundation.org/SportsLibrary/CFHSN/CFHSNv18/CFHSNv18n2c.pdf.

- ^ Clegg, Brian (2007). The Man Who Stopped Time. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0-309-10112-3.

- ^ "The World's Columbian Exposition (1893)". The American Experience. PBS. 1999. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/houdini/peopleevents/pande08.html. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ Adams, Cecil (2007-02-27). "What is the origin of the song "There's a place in France/Where the naked ladies dance?" Are bay leaves poisonous?". The Straight Dope. http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/2695/what-is-the-origin-of-the-song-theres-a-place-in-france-where-the-naked-ladies-dance. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ^ a b Terry Waldo (1991). This is Ragtime. Da Capo Press.

- ^ Crawford, pg. 539

- ^ Southern, pg. 329

- ^ W.C. Handy (1941). Father of the Blues. Da Capo Press.

- ^ Southern, pg. 283

- ^ Caldwell Titcomb (Spring 1990). "Black String Musicians: Ascending the Scale". Black Music Research Journal (Center for Black Music Research - Columbia College Chicago and University of Illinois Press) 10 (1): 107–112. doi:10.2307/779543. JSTOR 779543.

- ^ Brunvand, Jan Harold (1998). "Christensen, Abigail Mandana ("Abbie") Holmes (1852-1938)". American folklore: an encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 142. ISBN 9780815333500. http://books.google.com/?id=l0N_sedAATAC&lpg=PA142&dq=Abigail%20Christensen%20folklore&pg=PA142#v=onepage&q=Abigail%20Christensen%20folklore&f=false.

- ^ Diamond, Beverly; Barbara Benary. "Indonesian Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 1011–1023.

- ^ Stillman, Amy Ku'uleialoha. "Polynesian Music". The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. pp. 1047–1053.

- ^ HistoryLink Essay: Cutter, Kirtland Kelsey

- ^ Arts & Crafts Movement Furniture

- ^ Nepstad, Peter. "The Viking Shop in Jackson Park" (pdf). Hyde Park Historical Society. http://www.hydeparkhistory.org/herald/VikingShip.pdf. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ^ Smith, Gerry (2008-06-26). "Viking ship from 1893 Chicago world's fair begins much-needed voyage to restoration". Chicago Tribune (Tribune Company). http://featuresblogs.chicagotribune.com/theskyline/2008/06/viking-ship-fro.html. Retrieved 2009-01-24.

- ^ "Kate McPhelim Cleary: A Gallant Lady Reclaimed" Lopers.net. Accessed October 6, 2008.

- ^ Wonderful West Virginia magazine, August 2007 at pg. 6

- ^ Bolotin, Norman, and Christine Laing. The World's Columbian Exposition: the Chicago World's Fair of 1893. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002.

- ^ a b Chaim M. Rosenberg (2008). America at the fair: Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 229–230. ISBN 978-0-7385-2521-1.

- ^ John Birkinbine (1893) "Prominent Features of the World's Columbian Exposition", Engineers and engineering, Volume 10, p. 292; for the metric values see Ludwig Beck (1903). Die geschichte des eisens in technischer und kulturgeschiehtlicher beziehung: abt. Das XIX, jahrhundert von 1860 an bis zum schluss.. F. Vieweg und sohn. p. 1026.

- ^ Hermann Schirmer (1937). Das Gerät der Artillerie vor, in und nach dem Weltkrieg: Das Gerät der schweren Artillerie. Bernard & Graefe. p. 132. "Der Schritt von einer kurze 42-cm-Kanone L/33 zu einer Haubitze mit geringerer Anfangsgeschwindigkeit und einem um etwa 1/5 geringeren Geschossgewicht war nich sehr gross."

- ^ Robert de Boer (2009) Alexander Macfarlane in Chicago, 1893 from WebCite

- ^ Talen, Emily (2005).New Urbanism and American Planning: The Conflict of Cultures, p. 118. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-70133-3.

References

- Crawford, Richard (2001). America's Musical Life: A History. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04810-1.

- Southern, Eileen (1997). Music of Black Americans. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.. ISBN 0393038432.

- Petterchak, Janice A. (2003). Lone Scout: W. D. Boyce and American Boy Scouting. Rochester, Illinois: Legacy Press. ISBN 0965319873.

- Neuberger, Mary. 2006. "To Chicago and Back: Alecko Konstantinov, Rose Oil, and the Smell of Modernity" in Slavic Review, Fall 2006.

Further reading

- Appelbaum, Stanley (1980). The Chicago World's Fair of 1893. New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-23990-X

- Arnold, C.D. Portfolio of Views: The World's Columbian Exposition. National Chemigraph Company, Chicago & St. Louis, 1893.

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe. The Book of the Fair: An Historical and Descriptive Presentation of the World's Science, Art and Industry, As Viewed through the Columbian Exposition at Chicago in 1893. New York: Bounty, 1894.

- Barrett, John Patrick, Electricity at the Columbian Exposition. R.R. Donnelley, 1894.

- Bertuca, David, ed. "World's Columbian Exposition: A Centennial Bibliographic Guide". Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996. ISBN 0-313-26644-1

- Buel, James William. The Magic City. New York: Arno Press, 1974. ISBN 0-405-06364-4

- Burg, David F. Chicago's White City of 1893. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1976. ISBN 0-8131-0140-9

- Dybwad, G. L., and Joy V. Bliss, "Annotated Bibliography: World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago 1893." Book Stops Here, 1992. ISBN 0-9631612-0-2

- Glimpses of the World's Fair: A Selection of Gems of the White City Seen Through A Camera, Laird and Lee Publishers, Chicago: 1893, accessed February 13, 2009.

- Larson, Erik. Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America. New York: Crown, 2003. ISBN 0-375-72560-1.

- Photographs of the World's Fair: an elaborate collection of photographs of the buildings, grounds and exhibits of the World's Columbian Exposition with a special description of The Famous Midway Plaisance. Chicago: Werner, 1894.

- Reed, Christopher Robert. "All the World Is Here!" The Black Presence at White City. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-253-21535-8

- Rydell, Robert, and Carolyn Kinder Carr, eds. Revisiting the White City: American Art at the 1893 World's Fair. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1993. ISBN 0-937311-02-2

- Wells, Ida B. "The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition: The Afro-American's Contribution to Columbian Literature." Originally published 1893. Reprint ed., edited by Robert W. Rydell. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1999. ISBN 0-252-06784-3

External links

- The Columbian Exposition in American culture.

- Photographs of the 1893 Columbian Exposition

- Photographs of the 1893 Columbian Exposition from Illinois Institute of Technology

- Interactive map of Columbian Exposition

- Chicago Postcard Museum -- A complete collection of the 1st postcards produced in the U.S. for the 1893 Columbian Exposition.

- "Expo: Magic of the White City," a documentary about the World's Columbian Exposition narrated by Gene Wilder

- A large collection of stereoviews of the fair

- The Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on the World's Columbian Exposition.

- Columbian Theatre History and information about artwork from the U.S. Government Building.

- Photographs and interactive map from of the 1893 Columbian Exposition from the University of Chicago

- Video simulations from of the 1893 Columbian Exposition from UCLA's Urban Simulation Team

- 1893 Columbian Exposition Concerts

- Edgar Rice Burroughs' Amazing Summer of '93 - Columbian Exposition

- International Eisteddfod chair, Chicago, 1893

- Photographs of the Exposition from the Hagley Digital Archives

- 1893 Chicago World Columbia Exposition: A Collection of Digitized Books from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Preceded by

Exposition Universelle (1889)World Expositions

1893Succeeded by

Brussels International (1897)City of Chicago Chicago metropolitan area · State of Illinois · United States of America Architecture · Beaches · Climate · Colleges and Universities · Community areas · Culture · Demographics · Economy · Flag · Freeways · Geography · Government · History · Landmarks · Literature · Media · Music · Neighborhoods · Parks · Public schools · Skyscrapers · Sports · Theatre · Transportation

Category ·

Category ·  PortalCategories:

PortalCategories:- 1893 in the United States

- American architecture

- History of Chicago, Illinois

- History of the United States (1865–1918)

- Mesoamerican art exhibitions

- Pre-Columbian art exhibitions

- World's Columbian Exposition

- World's Fairs in Chicago, Illinois

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.