- Space tether

-

Artist's conception of satellite with a tether

Artist's conception of satellite with a tetherSpace tethers are cables, usually long and very strong, which can be used for propulsion, stabilization, or maintaining the formation of space systems by determining the trajectory of spacecraft and payloads.[1] Depending on the mission objectives and altitude, spaceflight using this form of spacecraft propulsion may be significantly less expensive than spaceflight using rocket engines.

Three main techniques for employing space tethers are in development:[2][3]

- Electrodynamic tether

- This is a conductive tether that carries a current that can generate thrust or drag from a planetary magnetic field, in much the same way as an electric motor.

- Momentum exchange tether

- This is a rotating tether that would grab a spacecraft and then release it at later time. Doing this can transfer momentum and energy from the tether to and from the spacecraft with very little loss; this can be used for orbital maneuvering.

- Tethered Formation Flying

- This is typically a non-conductive tether that accurately maintains a set distance between space vehicles.

- Electric Sail

- A form of solar wind sail with electrically charged tethers that will be pushed by the momentum of solar wind ions.

Contents

History

Tsiolkovsky once proposed a tower so tall that it reached into space, so that it would be held there by the rotation of the Earth. However, there was no realistic way to build it.

To try to solve the problems in Komsomolskaya Pravda (July 31, 1960), another Russian, Yuri Artsutanov, wrote in greater detail about the idea of a tensile cable to be deployed from a geosynchronous satellite; downwards towards the ground, and upwards away; keeping the cable balanced. This is the space elevator idea, a type of synchronous tether that would rotate with the Earth. However, given the materials, this too was impractical on Earth.

In the 1970s Jerome Pearson explored synchronous tethers[4] further, and in particular analysed the lunar elevator that can go through the L1 and L2 points, and this was found to be possible with materials then existing.

In 1977 Hans Moravec[5] and later Robert L. Forward investigated the physics of synchronous and non synchronous skyhook tethers, and performed detailed simulations of tapered tethers that could pick objects off and place objects onto the Moon, Mars and other planets, with little, or even a net gain of energy.[6][7]

In 1979 NASA examined the feasibility of the idea and gave direction to the study of tethered systems, especially tethered satellites.[1][8] In 2000, NASA and Boeing considered a HASTOL concept where a tether would take payloads from a hypersonic aircraft (at half of orbital velocity) to orbit.[9]

Missions

Main article: Space tether missionsA tether satellite is a satellite connected to another by a space tether.

Tether satellites can be used for various purposes including research into tether propulsion, tidal stabilisation and orbital plasma dynamics.

A number of tether satellites have been launched, with varying degrees of success.

Types

There are many different (and overlapping) types of tether.

Momentum exchange

Main article: momentum exchange tetherMomentum Exchange Tethers is one of many applications for space tethers. This sub-set represents an entire area of research using a spinning conductive and/or non-conductive tether to throw spacecraft up or down in orbit (like a sling), thereby transferring (or taking) its momentum.

The act of spinning a long tether end-for-end creates a controlled acceleration on the end-masses of the system and a tension in the tether. This spin is manipulated by control of the angular frequency. From this, momentum exchange can occur if an endbody is released at the right point during the controlled rotation. The transfer in momentum to the released object will cause the tether system to lose (or gain) orbital energy, and lose (or gain) altitude (and may require reboosting) or change orbital planes; and the opposite to happen to the released mass.

When in a magnetic field, such as in low earth orbit, when using an electrodynamic tether it is possible to re-boost without the expenditure of consumables. Other schemes involve balancing the momentum flow (such as catching and releasing payloads at almost the same time), or using conventional rocket propulsion or ion drives.

Electrodynamic

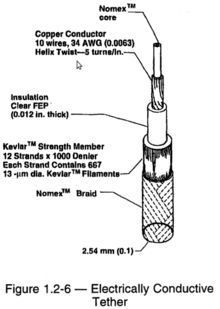

Main article: Electrodynamic tetherElectrodynamic tethers are long conducting wires, such as one deployed from a tether satellite, which can operate on electromagnetic principles as generators, by converting their kinetic energy to electrical energy, or as motors, converting electrical energy to kinetic energy.[1] Electric potential is generated across a conductive tether by its motion through the Earth's magnetic field. The choice of the metal conductor to be used in an electrodynamic tether is determined by a variety of factors. Primary factors usually include high electrical conductivity, and low density. Secondary factors, depending on the application, include cost, strength, and melting point.

Formation Flying

Main article: Tethered Formation FlyingThis is the use of a (typically) non-conductive tether to connect multiple spacecraft.

Space environment

Gravitational gradient stabilization

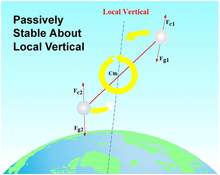

Main article: Gravity-gradient stabilizationInstead of rotating end for end, tethers can also be kept straight by the slight difference in the strength of gravity over their length.

A non-rotating tether system has a stable orientation that is aligned along the local vertical (of the Earth or other body.) This can be understood by inspection of the figure below where two spacecraft at two different altitudes have been connected by a tether. Normally, each spacecraft would have a balance of gravitational (e.g. F_g1) and centrifugal (e.g. F_c1), but when tied together by a tether these values begin to change with respect to one another. This phenomenon occurs because, without the tether, the higher altitude mass would travel slower than the lower mass. The system must move at a single speed, so the tether must therefore slow down the lower mass and speed up the upper one. The centrifugal force of the tethered upper body is increased while that of the lower altitude body is reduced. This results in the centrifugal force of the upper body and the gravitational force of the lower body being dominant. This difference in forces naturally aligns the system along the local vertical, as seen in the figure.[10]

Atomic oxygen

Objects in low earth orbit are subjected to noticeable erosion from monomolecular oxygen, due to the high orbital speed with which the molecules strike as well as their high reactivity.

Micrometeorites and space junk

Simple tethers are quickly cut by micrometeoroids and space junk. The lifetime of a simple, one-strand tether in space is on the order of five hours for a length of ten kilometers. This was originally a show stopper[citation needed] for the use of tethers.

Several systems have since been proposed and tested to improve debris resistance:

- The US Naval Research Laboratory has successfully flown a long term four kilometer tether that used very fluffy yarn. This satellite (TiPS) was launched in June 1996 and remained in operation over 10 years, finally breaking in July 2006[11].

- Dr. Robert P. Hoyt patented an engineered circular net, such that a cut strand's strains would be redistributed automatically around the severed strand. This is called a Hoytether. Hoytethers have theoretical lifetimes of tens of years.

- Researchers with JAXA have also proposed net-based tethers for their future missions[12].

- Another proposal is to use a tape or cloth.

Large pieces of junk would still cut most tethers, including the improved versions listed above, but these are currently tracked on radar and have predictable orbits. A tether could be wiggled to dodge known pieces of junk, or thrusters used to change the orbit, avoiding a collision.

Construction

Properties of useful materials

Tether properties and materials are dependent on the application. However, there are some common properties. To achieve maximum performance and low cost, tethers need to be made of materials with the combination of high strength or electrical conductivity and low density. All space tethers are susceptible to space debris or micrometeroids. Therefore, mission designers need to decide whether or not a protective coating is needed, including if against UV and atomic oxygen. Research is being conducted to assess the probability of a collision that would damage the tether MAST.

For applications that exert high tensile forces on the tether, the materials need to be strong and light. Some current tether designs use crystalline plastics such as ultra high molecular weight polyethylene, aramid or carbon fiber. A possible future material would be carbon nanotubes, which have an estimated tensile strength between 140 and 177 GPa (20.3-25.6 million psi), and a proven tensile strength in the range 50-60 GPa for some individual nanotubes. (A number of other materials obtain 10 to 20 GPa in some samples on the nano scale, but translating such strengths to the macro scale has been challenging so far, with, as of 2011, CNT-based ropes being an order of magnitude less strong, not yet stronger than more conventional carbon fiber on that scale).[13][14][15]

For some applications, the tensile force on the tether is less than 15 lbs (< 65 N)[16] Material selection in this case depends on the purpose of the mission and design constraints. Electrodynamic tethers, such as the one used on TSS-1R, may use thin copper wires for high conductivity (see EDT).

There are design equations for certain applications that can identify typical quantities that drive material selection.

Space elevator equations typically use a ‘characteristic length’ (Lc). Lc is also known as its 'self-support length' and is the length of untapered cable it can support in a constant 1g gravity field. Lc=σ/ρg, where σ is the stress limit (in pressure units) and ρ is the density of the material.

Hypersonic skyhook equations use the material’s ‘specific velocity’ which is equal to the maximum tangential velocity a spinning hoop can attain without breaking. Vs=√(σ/ρ).

For rotating tethers (rotovators) the value used is the material’s ‘characteristic velocity’ which is the maximum tip velocity a rotating untapered cable can attain without breaking. Vc=√(2σ/ρ). The characteristic velocity equals the specific velocity multiplied by the square root of two.

These values are used in equations similar to the rocket equation and are analogous to specific impulse or exhaust velocity. The higher these values are, the more efficient and lighter the tether can be in relation to the payloads that they can carry. Eventually however, the mass of the tether propulsion system will be limited at the low end by other factors such as momentum storage.

Practical materials

Materials proposed include Kevlar, ultra high molecular weight polyethylene, carbon nanotubes, M5 fiber, and diamond.

One material that has great potential is M5 fiber. This is a synthetic fiber that is lighter than Kevlar or Spectra.[17] According to Pearson, Levin, Oldson, and Wykes in their article "The Lunar Space Elevator," an M5 ribbon 30 mm wide and 0.023 mm thick, would be able to support 2000 kg on the lunar surface (2005). It would also be able to hold 100 cargo vehicles, each with a mass of 580 kg, evenly spaced along the length of the elevator.[4] Other materials that could be used are T1000G carbon fiber, Spectra 2000, or Zylon.[18] All of these materials have breaking lengths of several hundred kilometers under 1g (10 m/s²).[4]

Potential tether/elevator materials[4] Material Density

ρ

(kg/m³)Stress Limit

σ

(GPa)Char.

length

Lc=σ/ρg, (km)Specific

velocity

Vs=√(σ/ρ), (km/s)Char.

velocity

Vc=√(2σ/ρ), (km/s)Single-wall carbon nanotubes (individual nanotubes in lab) 2266 50 2200 4.7 6.6 Aramid, Polybenzoxazole (PBO) fiber ("Zylon")[18] 1340 5.9 450 2.1 3.0 Toray carbon fiber (T1000G) 1810 6.4 360 1.9 2.7 Magellan honeycomb polymer M5 (planned values) 1700 9.5 570 2.4 3.3 Magellan honeycomb polymer M5 (existing) 1700 5.7 340 1.8 2.6 Honeywell extended chain polyethylene fiber (Spectra 2000) 970 3.0 316 1.8 2.5 DuPont Aramid fiber (Kevlar 49) 1440 3.6 255 1.6 2.2 Specialty materials e.g. silicon carbide 3000 5.9 199 1.4 2.0 Aluminium (6061 T6) 2700 0.276 10. 0.32 0.45 Shape

Tapering

For gravity stabilised tethers, to exceed the self-support length the tether material can be tapered so that the cross-sectional area varies with the total load at each point along the length of the cable. In practice this means that the central tether structure needs to be thicker than the tips. Correct tapering ensures that the tensile stress at every point in the cable is exactly the same. For very demanding applications, such as an Earth Space Elevator, the tapering can result in excessive ratios of cable weight to payload weight.

Thickness

For rotating tethers not significantly affected by gravity, the thickness also varies, and it can be shown that the area, A, is given as a function of r (the distance from the centre) as follows:

where R is the radius of tether, v is the velocity with respect to the centre, M is the tip mass, δ is the material density, and T is the design tensile strength (Young's modulus divided by safety factor).

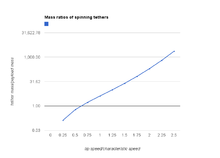

Mass ratio

Integrating the area to give the volume and multiplying by the density and dividing by the payload mass gives a payload mass/tether mass ratio of:

where erf is the normal probability error function

Let

,

,then:

This equation can be compared with the rocket equation, which is proportional to a simple exponent on a velocity, rather than a velocity squared. This difference effectively limits the delta-v that can be obtained from a single tether.

Redundancy

In addition the cable shape must be constructed to withstand micrometeorites and space junk. This can be achieved with the use of redundant cables, such as the Hoytether; redundancy can ensure that it is very unlikely that multiple redundant cables would be damaged near the same point on the cable, and hence a very large amount of total damage can occur over different parts of the cable before failure occurs.

Material strength

Beanstalks and rotovators are currently limited by the strengths of available materials. Although ultra-high strength plastic fibers (Kevlar and Spectra) permit rotovators to pluck masses from the surface of the Moon and Mars, a rotovator from these materials cannot lift from the surface of the Earth. In theory, high flying, supersonic (or hypersonic) aircraft could deliver a payload to a rotovator that dipped into Earth's upper atmosphere briefly at predictable locations throughout the tropic (and temperate) zone of Earth.

Cargo capture

Cargo capture for rotovators is nontrivial, and failure to capture can cause problems. Several systems have been proposed, such as shooting nets at the cargo, but all add weight, complexity, and another failure mode. At least one lab scale demonstration of a working grapple system has been achieved however.[21]

Life expectancy

Currently, the strongest materials in tension are plastics that require a coating for protection from UV radiation and (depending on the orbit) erosion by atomic oxygen. Disposal of waste heat is difficult in a vacuum, so over-heating may cause tether failures or damage.

Control and modelling

Pendular motion instability

Electrodynamic tethers deployed along the local vertical ('hanging tethers') may suffer from dynamical instability. Pendular motion causes the tether vibration amplitude to build up under the action of electromagnetic interaction. As the mission time increases, this behavior can compromise the performance of the system. Over a few weeks, electrodynamic tethers in Earth orbit might build up vibrations in many modes, as their orbit interacts with irregularities in magnetic and gravitational fields.

One plan to control the vibrations is to actively vary the tether current to counteract the growth of the vibrations. Electrodynamic tethers can be stabilized by reducing their current when it would feed the oscillations, and increasing it when it opposes oscillations. Simulations have demonstrated that this can control tether vibration.[citation needed] This approach requires sensors to measure tether vibrations, which can either be an inertial navigation system on one end of the tether, or satellite navigation systems mounted on the tether, transmitting their positions to a receiver on the end.

Another proposed method is to utilise spinning electrodynamic tethers instead of hanging tethers. The gyroscopic effect provides passive stabilisation, avoiding the instability.

Surges

As mentioned earlier, conductive tethers have failed from unexpected current surges. Unexpected electrostatic discharges have cut tethers (e.g. see Tethered Satellite System Reflight (TSS-1R) on STS-75), damaged electronics, and welded tether handling machinery. It may be that the Earth's magnetic field is not as homogeneous as some engineers have believed.

Vibrations

Computer models frequently show tethers can snap due to vibration.

Mechanical tether-handling equipment is often surprisingly heavy, with complex controls to damp vibrations. The one ton climber proposed by Dr. Brad Edwards for his Space Elevator may detect and suppress most vibrations by changing speed and direction. The climber can also repair or augment a tether by spinning more strands.

The vibration modes that may be a problem include skipping rope, transverse, longitudinal, and pendulum.[22]

Tethers are nearly always tapered, and this can greatly amplify the movement at the thinnest tip in whip like ways.

Other issues

A tether is not a spherical object, and has significant extent. This means that as an extended object, it is not directly modelable as a point source, and this means that the center of mass and center of gravity are not usually colocated. Thus the inverse square law does not apply except at large distances, to the overall behaviour of a tether. Hence the orbits are not completely Keplerian, and in some cases they are actually chaotic.[citation needed]

With bolus designs, rotation of the cable interacting with the non linear gravity fields found in elliptical orbits can cause exchange of orbital angular momentum and rotation angular momentum. This can make prediction and modelling extremely complex.

In fiction

The mechanics of tether propulsion are critical in resolving the climax of the book The Descent of Anansi by Steven Barnes and Larry Niven.

See also

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Non-rocket spacelaunch

- Lofstrom launch loop - cable-like launch system

- Orbital ring - a ring around the Earth

- Space fountain

References

- ^ a b c NASA, Tethers In Space Handbook, edited by M.L. Cosmo and E.C. Lorenzini, Third Edition December 1997 (accessed 20 October 2010); see also version at NASA MSFC; available on scribd

- ^ Finckenor, Miria; AIAA Technical Committee (December 2005). "Space Tether". Aerospace America: 78.

- ^ Bilen, Sven; AIAA Technical Committee (December 2007). "Space Tethers". Aerospace America: 89.

- ^ a b c d Pearson, Jerome; Eugene Levin, John Oldson and Harry Wykes (2005). "Lunar Space Elevators for Cislunar Space Development Phase I Final Technical Report" (PDF). http://www.niac.usra.edu/files/studies/final_report/1032Pearson.pdf.

- ^ The Journal of the Astronautical Sciences, v25#4, pp. 307-322, Oct-Dec 1977

- ^ Hans Moravec "Orbital Bridges," (1986) (accessed Oct. 10, 2010)

- ^ Hans Moravec, "Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhooks for the Moon and Mars with Conventional Materials" (Hans Moravec's thoughts on skyhooks, tethers, rotovators, etc., as of 1987) (accessed 10 October 2010)

- ^ Joseph A. Carroll and John C. Oldson, "Tethers for Small Satellite Applications", presented at the 1995 AIAA/USU Small Satellite Conference in Logan, Utah (accessed 20 October 2010)

- ^ "Hypersonic Airplane Space Tether Orbital Launch System". NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts. December 1998. http://www.spaceelevator.com/docs/355Bogar.pdf. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ Cosmo, M.L., Lorenzini, E.C., "Tethers in Space Handbook," NASA Marchall Space Flight Center, 1997, pp. 274-1-274

- ^ NOSS Launch Data (see NOSS 2-3, which deployed TiPS)

- ^ Ohkawa, Y., Kawamoto, S., Nishida, S., and Kitamura, S., "Research and Development of Electrodynamic Tethers for Space Debris Mitigation", Trans. JSASS Space Tech. Japan, Vol. 7 (2009), pp.Tr_2_5-Tr_2_10.

- ^ Nanotube Fibers

- ^ Tensile tests of ropes of very long aligned multiwall carbon nanotubes

- ^ Tensile Loading of Ropes of Single-Wall Carbon Nanotubes and their Mechanical Properties

- ^ NASA, TSS-1R Mission Failure Investigation Board, Final Report, May 31, 1996 (accessed 7 April 2011)

- ^ Bacon 2005

- ^ a b Specifications for commercially available PBO (Zylon) cable: "PBO (Zylon) The high performance fibre" (accessed Oct. 20, 2010)

- ^ a b "Tether Transport from LEO to the Lunar Surface", R.L. Forward, AIAA Paper 91-2322, 27th Joint Propulsion Conference, 1991

- ^ Non-Synchronous Orbital Skyhooks for the Moon and Mars with Conventional Materials - Hans Moravec

- ^ http://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/news/news/releases/2005/05-108.html NASA Engineers, Tennessee College Students Successfully Demonstrate Catch Mechanism for Future Space Tether

- ^ Tether dynamics

External links

- ProSEDS, a tether-based propulsion experiment

- Special Projects Group

- NASA Tether Overview

- Tethers Unlimited Incorporated

- "Tethers In Space Handbook" M.L. Cosmo and E.C. Lorenzini Third Edition December 1997

- NASA IAC report on orbital systems

- SpaceTethers.com, space tether simulator applet

- Npr.org - Space Tethers: Slinging Objects in Orbit?

- ESA - The YES2 project

- ESA - Students test 'space postal service' during Foton mission

- The Space Show #531 Robert P. Hoyt discusses space tethers on The Space Show.

- NASA site on TSS-1R

- NASA Tether Origami

- New Scientist article

- Tether Physics and Survivability Experiment

- Tethers Unlimited: Publications

- Tethers in Space Handbook (PDF)

Spacecraft propulsion Chemical

rocketsStatePropellantsLiquid propellants (Cryogenic · Hypergolic) · Monopropellant · Bipropellant (Staged combustion cycle · Expander cycle · Gas-generator cycle · Pressure-fed cycle) · TripropellantElectrical

thrustersElectrostaticElectromagneticElectrothermalOtherNuclear

propulsionClosed systemOpen systemOther Space elevator Main articles

Concepts Technologies Competitions Space elevator games · Elevator:2010 · European Space Elevator Challenge · Japan Space Elevator & Technical CompetitionPeople Organizations Categories:- Reusable space launch systems

- Single-stage-to-orbit

- Space elevator

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Vertical transport devices

- Satellites

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.