- Munson Valley Historic District

-

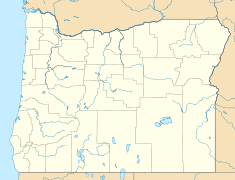

Munson Valley Historic District

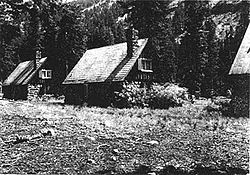

The Crater Lake National Park administration building at Munson Valley.

The Crater Lake National Park administration building at Munson Valley.Location: Crater Lake National Park, Oregon Nearest city: Fort Klamath, Oregon Coordinates: 42°53′50″N 122°08′03″W / 42.89722°N 122.13417°W Area: 7.5 acres (3.0 ha) (original)

6 acres (2.4 ha) (decreased)Built: 1926[1] Architect: National Park Service, Merel Sager[3] Architectural style: National Park Service rustic[4] Governing body: National Park Service MPS: Crater Lake National Park MRA NRHP Reference#: 88002622[1][2] Added to NRHP: December 1, 1988[1] Munson Valley Historic District is the headquarters and main support area for Crater Lake National Park in southern Oregon. The National Park Service chose Munson Valley for the park headquarters because of its central location within the park. Because of the unique rustic architecture of the Munson Valley buildings and the surrounding park landscape, the area was listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 1988. The district has eighteen contributing buildings, including the Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence which is a U.S. National Historic Landmark and separately listed on the NRHP. The district's NRHP listing was decreased in area in 1997.

Contents

Early history

Crater Lake lies inside a caldera created 7,700 years ago when the 12,000-foot (3,700 m) high Mount Mazama collapsed following a large volcanic eruption. Over the following millennium, the caldera was filled with rain water forming today’s lake.[5] The Klamath Indians revered Crater Lake for its deep blue waters. In 1853, three gold miners found the lake. They named it Deep Blue Lake, but because the lake was so high in the Cascade Mountains the discovery was soon forgotten.[6]

In 1886, William Gladstone Steel accompanied a United States Geological Survey party led by Captain Clarence Dutton to survey Crater Lake. The team carried a half-ton survey boat, the Cleetwood, up the steep mountain slope and lowered it 2,000 feet (610 m) into the lake. During the visit, Steel named many of the lake's landmarks including Wizard Island, Llao Rock, and Skell Head. The lake’s natural beauty made a great impression on Steel. As a result, when he returned from survey trip, he began advocating that Crater Lake be established as a national park.[6]

On 22 May 1902, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the bill making Crater Lake the Nation's sixth national park. The United States Department of the Interior was charged with developing road access and visitor services for the park. This was a difficult job because of the park’s remote location at the summit of the Cascade Mountains. By 1905, a "steep and tortuous" road to the crater rim had been completed. This access road was essential for the future development of the park.[7]

In 1913, Congress appropriated funds for the Army Corps of Engineers to build a road around Crater Lake. The initial road survey identified the northern end of Munson Valley, three miles (5 km) south of the rim, as the best site for the road crew’s seasonal headquarters and supply depot. Not only was Munson Valley a central location, the surrounding valley provided timber for expanding the park facilities. However, United States entry into World War I slowed development of park infrastructure. The road around the lake was finally finished 1918. Once the road was completed, the National Park Service continued to use the Munson Valley site as a staging area for development projects throughout the park.[4]

Government Camp

By 1924, the Munson Valley facilities were known as "Government Camp" and the site had become the park’s summer headquarters. Though the site had adequate space, the facilities were poorly designed and cheaply constructed. In 1925, National Park Service approved a master plan for developing Munson Valley. The development program began in 1927, and was overseen by the National Park Service’s Landscape Engineering Division, headed by Thomas C. Vint. The major components of the plan included construction of new administrative buildings, a new maintenance area, living quarters for park staff and seasonal employees, and general support buildings.[4]

Between 1927 and 1930, a park warehouse, mess hall, bear-proof meat-house, comfort station with employee restrooms and showers, four small cottages, and two utility buildings were built. All these structures were designed in a common rustic style using timber from nearby stands and locally quarried stone.[4]

Between 1932 and 1936, houses for the park superintendent, park naturalist, and several other employees were completed along with four more utility buildings, a second comfort station, and a dormitory for park rangers. The old log headquarters building was demolished and a new rustic stone structure built in its place. The plaza in front of the new administration building had a landscaped island in the center with space to park 50 cars around the outside. During this period, Civilian Conservation Corps crews planted over a thousand trees and several thousand shrubs in the Government Camp area. In addition, many small features such as flagstone walks, rustic signs, stone bridges, and drinking fountains were incorporated into the landscape. In 1938, Government Camp was re-named "Park Headquarters" by Superintendent Ernest P. Leavitt.[4]

Development in Crater Lake National Park was curtailed during World War II. Maintenance became the primary concern of the park staff, as Civilian Conservation Corps manpower disappeared with the onset of the war. This began a period of decline in park facilities.[7]

Park Headquarters

Legend 1. Administration building

Legend 1. Administration building

2. Ranger dormitory

3. Mess hall

4. Warehouse

5. Machine shop

8. Oil and gas house

13. Meat house

19. Superintendent's residence

20. Naturalist's residence

24, 25, 28, 30, 31, 32. Residences

33. Stone shed/garage

34. Hospital

36. Transformer building

37. Comfort station Munson Valley Historic District has 18 buildings.After World War II, the National Park Service began using the Munson Valley complex year-around. This had a tremendous impact on the historic landscape. Many landscape features including curbing, planting beds, and walkways had to be removed in order to widen narrow road to accommodate snow plows. Some porches had to be removed and snow tunnels were added to buildings for winter access. In 1954, all of the planters, lawns, and walks around the employee cottages were removed to facilitate snow removal. The traffic island near the upper group of cottages was also removed along with several utility buildings in the maintenance area to allow space for snow plows to turn around.[4]

Over the years, there were other changes as well. The Fire Hall was demolished in 1969. In 1986, the ranger dormitory and the administration building were remodeled. A new snow tunnel was added to the west side of the administration building replacing the south entrance tunnel built in 1958. In 1990, several rustic utility buildings were torn down, and a gas station was removed in 1992. Despite the loss of landscape and original structures, the headquarters complex still reflects the original Munson Valley master plan and is a good example of the National Park Service rustic architecture.[4] As a result, the area was listed as a historic district on the National Register of Historic Places in 1988 (NRHP #88002622).[8] The historic area was at first 7.5 acres (3 ha) but was later reduced to 6 acres (2 ha).[2][9]

Structures

There are eighteen primary structures in the Munson Valley Historic District. While most of the buildings have been remodeled, they still reflect the rustic style of architecture which is the common design theme that makes the Munson Valley headquarters complex historically unique.[4]

Munson Valley Historic District extends south from the Superintendent's Residence and ends at the park warehouse at the north end of the maintenance area. The eighteen historic structures were built between 1926 and 1949. They include the, from north to south, the Superintendent's Residence, the park Naturalist's Residence, a cluster of staff residence cabins, the Administration Building, Ranger Dormitory, Transformer Building, Comfort Station, Mess Hall, Warehouse, and Machine Shop.[4][10]

- The park Superintendent's Residence is located at north end of headquarters area. It was constructed in 1933. The building’s footprint is 33 by 61 feet (10 m × 18.6 m) with a rustic stone superstructure and wood-shake roof. The first floor includes an entry hall, living room with lava-rock fireplace, a dining room, kitchen, and bedroom with adjoining bathroom. The second floor has four additional bedrooms and two bathrooms. The building was framed in Douglas fir and the roof covered with cedar shakes.[11] The Crater Lake Superintendent's Residence is a U.S. National Historic Landmark and is individually listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP #87001347).[8] Today, the building houses part of the park’s Science and Learning Center.[12]

- The park Naturalist's Residence is located between the Superintendent's Residence and the other employee houses near the north end of the historic district. The building’s footprint is the same as the Superintendent's Residence; however, the floor plan is slightly different. This first floor contained a living room with stone fireplace, a kitchen, breakfast room, bedroom, and bathroom. There are three additional bedrooms and a bath room upstairs.[11] Today, the building houses part of the park’s Science and Learning Center.[12]

- The historic district also includes six rustic stone Employee Cottages built for park staff between 1927 and 1931. These housing units are designated as buildings #24, 25, 28, 30, 31, and 32. They are architecturally significant because they were part of the original Munson Valley headquarters master plan, and were constructed in the rustic style using native stone and timber. While aluminum roofs were added in the mid-1950s, these units still retain their original character.[10]

- The park Administration Building was built with a rough stone first story with rustic superstructure. It is 100 feet (30 m) long and 40 feet (12 m) wide. The main entrance led into a public lobby with a large fireplace and wood-paneled walls. Offices for the superintendent, assistant superintendent, comptroller, and information department were also on the first floor along with a large 42 by 15 feet (12.8 m × 4.6 m) room for the park’s clerical staff. The second floor has six additional offices and two storage rooms.[11]

- The Ranger Dormitory was begun in 1932, but was not finished until 1936 due to lack of funds. It is constructed of native stone and timber. Originally, the first floor had an entry hall, men’s and women’s bathrooms, and two living rooms, each with its own stone fireplace. The larger living room, located in the north end of the building, was for men. A smaller living room plus three other rooms and a shower at the south end of the building were for women. The second floor had four bedrooms, a large 18 by 34 foot (5.5 m × 10.4 m) dormitory room, a dark room, storage room, and men’s shower. There is also a basement under the central portion of the building.[11] Today, the National Park Service uses the building as its main visitor center. The William G. Steel Information Center is open to the public year-round. Visitor to the park can obtain general information, park maps, and backcountry permits at the center. The center has exhibits and an audio-visual program. First aid care is also available at the center.[13]

The historic district also includes various utility buildings including a mess hall, meat house, transformer building, comfort station (later converted to a sign shop), warehouse, and machine shop. These buildings all share common structural design elements that typify the park’s rustic style of architecture including massive stone masonry, rough-sawn board siding, stained timber beams, dormer windows, and steep pitched roofs.[11]

At Munson Valley, rustic structures successfully blend with the natural environment. The buildings in the historic district are excellent examples of the rustic style of architecture, and represent one of the National Park Service's most successful development programs. In addition, the landscape surrounding the historic district remains virtually intact. As a result, the Munson Valley Historic District is significant as an expression of American naturalistic design.[4]

Access

Munson Valley is located high in the Cascade Mountains, 6,450 feet (1,966 m) above sea level. It is sixty miles (97 km) north of Klamath Falls, Oregon. The Munson Valley Historic District is three miles (5 km) south of Crater Lake and the Rim Village visitor area which is also a historic district (NRHP #97001155). In the Crater Lake area, winter lasts eight months with an average snowfall of 533 inches (1,354 cm) per year, and many snow banks remain well into the summer.[14] While most park roads are closed in the winter, the park headquarters, visitor center, and the other Munson Valley facilities are open year-around. However, winter storms make driving in the Crater Lake area unpredictable. During the summer, weather is generally warm, but nights are often quite cool.[13][14] The National Park Service charges a $10 fee for private passenger vehicles entering the park. Commercial vehicles are charged between $25 and $200 depending on the vehicle's capacity.[9]

See also

- List of Registered Historic Places in Oregon

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Oregon

References

- ^ a b c Oregon Parks and Recreation Department (2007-07-16). "Oregon National Register List". http://www.oregonheritage.org/OPRD/HCD/NATREG/docs/oregon_nr_list.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-29

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2009-03-13. http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natreg/docs/All_Data.html.

- ^ National Park Service. "National Register Information System". Archived from the original on 2008-03-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20080328191605/http://www.cr.nps.gov/NR/research/nris.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gilbert, Cathy and Marsha Tolon,"History", Cultural Landscape Recommendations: Park Headquarters at Munson Valley, Crater Lake National Park, National Park Service, Department of Interior, July 1990.

- ^ "Crater Lake - Like No Place Else on Earth", Crater Lake National Park, National Park Service, United States Department of Interior, 8 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Park History", Crater Lake National Park, National Park Service, United States Department of Interior, 8 March 2008.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Cathy A. and Gretchen A. Luxenburg, "Historic Overview", The Rustic Landscape of Rim Village, 1927-1941, National Park Service, Department of Interior, Seattle, Washington, 1990.

- ^ a b "Munson Valley Historic District", National Register of Historic Places, www.nationalregisterofhistoricalplaces.com, 12 March 2008.

- ^ a b "Facts and Figures", National Park Service, Department of Interior, Crater Lake, Oregon, November 2001.

- ^ a b Green, Linda W., "Summary of Important Structures", Crater Lake Historic Resource Study, National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, Denver, Colorado, June 1984.

- ^ a b c d e Green, Linda W., "Construction of Government Buildings and Landscaping in Crater Lake National Park", Crater Lake Historic Resource Study, National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, Denver, Colorado, June 1984.

- ^ a b "Munson Valley Historic District", Crater Lake National Park Trust, Crater Lake, Oregon, 8 April 2008.

- ^ a b "Munson Valley", National Park Service, United States Department of Interior, May 2001.

- ^ a b "Weather", National Park Service, United States Department of Interior, 7 April 2008.

External links

Crater Lake Natural places Man-made places People Designated areas Crater Lake National Park • Munson Valley Historic District • Rim Drive • Rim Village Historic District • Volcanic Legacy Scenic BywayU.S. National Register of Historic Places in Oregon Lists by county Baker • Benton • Clackamas • Clatsop • Columbia • Coos • Crook • Curry • Deschutes • Douglas • Gilliam • Grant • Harney • Hood River • Jackson • Jefferson • Josephine • Klamath • Lake • Lane • Lincoln • Linn • Malheur • Marion • Morrow • Multnomah: Portland North • Multnomah: Portland Northeast • Multnomah: Portland Northwest • Multnomah: Portland Southeast • Multnomah: Portland Southwest • Multnomah: Other • Polk • Sherman • Tillamook • Umatilla • Union • Wallowa • Wasco • Washington • Wheeler • Yamhill

Other lists Categories:- Historic districts in Oregon

- Civilian Conservation Corps in Oregon

- Crater Lake

- Rustic architecture

- National Register of Historic Places in Klamath County, Oregon

- Buildings and structures in Klamath County, Oregon

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.