- King Kong vs. Godzilla

-

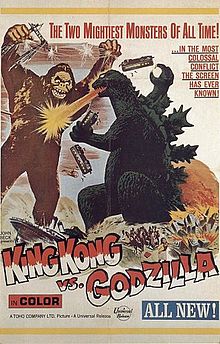

King Kong vs. Godzilla

Original theatrical posterDirected by Ishirō Honda Produced by Tomoyuki Tanaka Written by Shinichi Sekizawa

George Worthing Yates (original script)

Willis O'Brien (original idea)Starring Tadao Takashima

Kenji Sahara

Yu Fujiki

Ichirō Arishima

Mie Hama

Shoichi Hirose

Haruo NakajimaMusic by Akira Ifukube

Sei Ikeno

Hachiro Matsui

BukimashaCinematography Hajime Koizumi Studio Toho Distributed by Toho (Japan)

Universal International (non-Asian territories)Release date(s) Japan:

August 11, 1962

United States:

June 26, 1963Running time Japanese version:

97 minutes

English version:

91 minutesCountry Japan Language Japanese, English, Tagalog Budget ¥5,000,000 Box office ¥350,000,000 King Kong vs. Godzilla (キングコング対ゴジラ Kingu Kongu Tai Gojira) is a 1962 Japanese science fiction kaiju film produced by Toho Studios. Directed by Ishirō Honda with visual effects by Eiji Tsuburaya, the film starred Tadao Takashima, Kenji Sahara, and Mie Hama. It was the third installment in the Japanese series of films featuring the monster Godzilla. It was also the first of two Japanese made films featuring the King Kong character and also the first time both King Kong and Godzilla appeared on film in color and widescreen. Produced as part of Toho's 30th anniversary celebration, this film remains the most commercially successful of all the Godzilla films to date.

Contents

Plot

Mr. Tako, head of Pacific Pharmaceuticals, is frustrated with the television shows his company is sponsoring and wants something to boost his ratings. When a doctor tells Tako about a giant monster he discovered on the small Faro Island, Tako believes that it would be a brilliant idea to use the monster to gain publicity. Tako immediately sends two men, Sakurai and Kinsaburo, to find and bring back the monster from Faro.

Meanwhile, the American submarine Seahawk gets caught in an iceberg. Unfortunately, this is the same iceberg that the mutant dinosaur Godzilla was trapped in by the Japanese Self-Defense Forces back in 1955, and the submarine is destroyed by the monster. As an American rescue helicopter circles the iceberg, Godzilla breaks out and heads towards a nearby Arctic military base, attacking it. The base itself is ineffective against Godzilla. He continues moving inland, razing the base to the ground, and sends the tank armory up in flames. Godzilla's appearance is all over the press, making Tako furious.

On Faro Island, a giant octopus (known as the Oodako) attacks the native village. The mysterious Faro monster is then revealed to be the giant gorilla, King Kong and he arrives and defeats the octopus. King Kong then drinks some red berry juice, becomes intoxicated, and then falls asleep. Sakurai and Kinsaburo place Kong on a large raft and begin to transport him back to Japan. Back at Pacific Pharmaceuticals, Tako is finally glad because Kong is now all over the press instead of Godzilla. Mr. Tako arrives on the ship transporting Kong, but a JSDF ship stops them and orders them to return Kong to Faro Island. Godzilla had just come ashore in Japan and destroyed a train, and the JSDF doesn't want another monster entering Japan. Unfortunately, during all this, Kong wakes up from his drunken state and breaks free from the raft. Reaching the mainland, Kong meets up with Godzilla in a valley. Tako, Sakurai, and Kinsaburo have difficulty avoiding the JSDF to watch the fight. Eventually they find a spot. Kong throws some large rocks at Godzilla, but Godzilla shoots his atomic breath at Kong's chest, forcing the giant ape to retreat.

The JSDF desperately tries everything to stop Godzilla from entering Tokyo. In a fielded area outside the city, they dig a large pit laden with explosives and lure Godzilla into it, but Godzilla is unharmed. They next string up a barrier of power lines around the city filled with a 1,000,000 volts of electricity (300,000 volts had been tried in the first film, but failed to turn the monster back). The electricity is too much for Godzilla, who then moves away from the city towards the Mt. Fuji area. Later at night, Kong approaches Tokyo. He tears through the power lines, feeding off the electricity which seems to make him stronger. Kong then attacks Tokyo and holds Fumiko, a woman from a train and Sakurai's sister, hostage. The JSDF explodes capsules full of the berry juice from Faro Island and knock out Kong, while Sakurai rescues Fumiko. The JSDF then decides to transport Kong via balloons to Godzilla, in hope that they will fight each other to their deaths.

The next morning, King Kong is dumbo-dropped onto the summit of Mt. Fuji from the balloon air-lift, meets up with Godzilla, and the two begin to fight. Godzilla has the advantage at first, eventually knocking Kong down with a vicious drop kick, and battering the gorilla unconscious with powerful tail attacks to his forehead. When Godzilla tries to kill Kong with his atomic breath, an electrical storm arrives and revives Kong, giving him the power of an electric grasp. The two begin to fight again, with the revitalized Kong swinging Godzilla around by his tail, shoving a tree into Godzilla's mouth, and judo tossing him over his shoulder. The brawl between the two monsters continues all the way down to the coastline. Eventually the monsters tear through Atami Castle and Kong drags Godzilla into the Pacific Ocean. After an underwater battle, only King Kong emerges from the water and begins to slowly swim back home to Faro Island. As Kong swims home, onlookers aren't sure if Godzilla survived the underwater fight, but speculate that it was possible.

Production

The film had its roots in an earlier concept for a new King Kong feature developed by Willis O'Brien, animator of the original stop-motion Kong. Around 1960, O'Brien came up with a proposed treatment, King Kong vs. Frankenstein,[1] where Kong would fight against a giant version of Frankenstein's monster in San Francisco.[2] O'Brien took the project (which consisted of some concept art[3] and a screenplay treatment) to RKO to secure permission to use the King Kong character. During this time the story was renamed King Kong vs. the Ginko[4] when it was believed that Universal had the rights to the Frankenstein name (they actually only had the rights to the monster's makeup design). O'Brien was introduced to producer John Beck who promised to find a studio to make the film (at this point in time RKO was no longer a production company). Beck took the story treatment and had George Worthing Yates flesh it out into a screenplay. The story was slightly altered and the title changed to King Kong vs. Prometheus, returning the name to the original Frankenstein concept (The Modern Prometheus was the alternate name of Frankenstein in the original novel). Unfortunately, the cost of stop animation discouraged potential studios from putting the film into production. After shopping the script around overseas, Beck eventually attracted the interest of the Japanese studio Toho. Toho had long wanted to make a King Kong film and decided to replace the Frankenstein creature with their own monster Godzilla. They thought it would be the perfect way to celebrate their thirtieth year in production.[5] John Beck's dealings with Willis O'Brien's project were done behind his back, and O'Brien was never credited for his idea.[6] In 1963, Merian C. Cooper attempted to sue John Beck claiming that he outright owned the King Kong character, but the lawsuit never went through as it turned out he was not Kong's sole legal owner as he had previously believed.[7]

Special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya was planning on working on other projects at this point in time such as a new version of a fairy tale film script called Kaguyahime (Princess Kaguya), but he postponed those to work on this project with Toho instead since he was such a huge fan of King Kong. He stated in a early 1960s interview with the Mainichi Newspaper, "But my movie company has produced a very interesting script that combined King Kong and Godzilla, so I couldn't help working on this instead of my other fantasy films. The script is special to me; it makes me emotional because it was King Kong that got me interested in the world of special photographic techniques when I saw it in 1933." [8]

Eiji Tsuburaya had a stated intention to move the Godzilla series in a lighter direction. This approach was not favoured by most of the effects crew, who "couldn't believe" some of the things Tsuburaya asked them to do, such as Kong and Godzilla volleying a giant boulder back and forth. But Tsuburaya wanted to appeal to children's sensibilities and broaden the genre's audience.[9] This approach was favoured by Toho and to this end, King Kong vs. Godzilla has a much lighter tone than the previous two Godzilla films and contains a great deal of humor within the action sequences. With the exception of the next film, Mothra vs Godzilla, this film began the trend to portray Godzilla and the monsters with more and more anthropomorphism as the series progressed, to appeal more to younger children. Ishirô Honda was not a fan of the dumbing down of the monsters.[10] Years later Honda stated in an interview. "I don't think a monster should ever be a comical character." "The public is more entertained when the great King Kong strikes fear into the hearts of the little characters."[11] The decision was also taken to shoot the film in a (2.35:1) scope ratio (Tohoscope) and to film in color (Eastman Color), marking both monsters' first widescreen and color portrayals.

Toho had planned to shoot this film on location in Sri Lanka, but had to forgo that (and scale back on production costs) because they ended up paying RKO roughly $200,000 (US) for the rights to the King Kong character. The bulk of the film was shot on Oshima (an island near Japan) instead.[12] The movie's production budget came out to ¥5,000,000.[13]

Suit actors Shoichi Hirose (King Kong) and Haruo Nakajima (Godzilla) were given a mostly free rein by Eiji Tsuburaya to choreograph their own moves. The men would rehearse for hours and would base their moves on that from professional wrestling (a sport that was growing in popularity in Japan).[14]

During pre-production, Ishirō Honda had toyed with the idea of using Willis O'Brien's stop motion technique instead of the suitmation process used in the first two Godzilla films, but budgetary concerns prevented him from using the process, and the more cost efficient suitmation was used instead. However, some brief stop motion was used in a couple of quick sequences. One of these sequences was animated by Koichi Takano[15] who was a member of Eiji Tsuburaya's crew.

A brand new Godzilla suit was designed for this film and some slight alterations were done to his overall appearance. These alterations included the removal of his tiny ears, 3 toes on each foot rather than four, enlarged central dorsal fins and a bulkier body. These new features gave Godzilla a more reptilian/dinosaurian appearance.[16] Outside of the suit, a meter high model and a small puppet were also built. Another puppet (from the waist up) was also designed that had a nozzle in the mouth to spray out liquid mist simulating Godzilla's fire breath. However the shots in the film where this prop was employed (far away shots of Godzilla breathing his fire during his attack on the Arctic Military base) were ultimately cut from the film.[17] These cut scenes can be seen in the Japanese theatrical trailer. Finally a separate prop of Godzilla's tail was also built for closeup practical shots when his tail would be used (such as the scene where Godzilla trips Kong with his tail). The tail prop would be swung offscreen by a stage hand.

The King Kong suit for this film has widely been considered to be one of the least appealing and insipid gorilla suits in film history [18] Sadamasa Arikawa (who worked with Eiji Tsuburaya) said that the sculptures had a hard time coming up with a King Kong suit that appeased Tsuburaya.[9] The first suit was rejected for being too fat with long legs giving Kong an almost cute look.[9] A few other designs were done before Tsuburaya would approve the final look that was ultimately used in the film. The suit was given two separate masks and two separate pairs of arms. Long arm extensions which contained poles inside the arms for Hirose to grab onto and with static immovable hands was used for long shots of Kong, while short human length arms were added to the suit for scenes that required Kong to grab items and wrestle with Godzilla.[19] Besides the suit with the two separate arm attachments, a meter high model and a puppet of Kong (used for closeups) were also built.[20][21] As well, a huge prop of Kong's hand was built for the scene where he grabs Mie Hama (Fumiko) and carries her off.[22]

For the attack of the giant octopus, four live octopuses were used. They were forced to move among the miniature huts by having hot air blown onto them. After the filming of that scene was finished, three of the four were released. The fourth became special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya's dinner. Along with the live animals, two rubber octopus props were built, with the larger one being covered with plastic wrap to simulate mucus. Some stop motion tentacles were also created for the scene where the octopus grabs a native and tosses him.[23]

Since King Kong was seen as the bigger draw (at the time, he was even more popular in Japan than Godzilla), and since Godzilla was still a villain at this point in the series, it led to the decision to not only give King Kong top billing, but also to present him as the winner of the climactic fight. While the ending of the film does look somewhat ambiguous, Toho confirmed that King Kong was indeed the winner in their 1962/63 English-language film brochure Toho Films Vol. 8, which states in the film's plot synopsis, A spectacular duel is arranged on the summit of Mt. Fuji, and King Kong is victorious. But after he has won...[24]

English version

When John Beck sold the King Kong vs. Prometheus script to Toho (which became King Kong vs. Godzilla), he was given exclusive rights to produce his own version of the film.[25] Beck was able to line up a couple of potential distributors in Warner Brothers and Universal Pictures International even before the film began production.

After the film was completed, Beck was given a private screening of the film and didn't like the comedic aspect of the film (the original Japanese version is a satire of commercialism). He went to work on his version and tried to turn the film into a straight sci-fi story. This resulted in what would be the most altered Godzilla film from its original Japanese version to the English version in the film series history. Beck removed much of the overt comedy from the original version of the film, cutting out huge amounts of Japanese dialogue which consisted primarily of character development. He replaced this footage with newly shot scenes of Eric Carter, a UN reporter who spends much of the time commenting on the action from a UN communication satellite broadcast, as well of Arnold Johnson, the head of the Museum of Natural History in New York, who tries to explain Godzilla's origin and his and Kong's motivations.[26] The new footage was directed by Thomas Montgomery.[27]

Beck was able to secure a deal with Universal Pictures International during this time as a distributor and was able to obtain from them library music from some of their older films (music tracks that had been composed by Henry Mancini, Hans J. Salter, and even a track from Heinz Roemheld). These films include Creature from the Black Lagoon, Bend of the River, Untamed Frontier, The Golden Horde, Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman, Man Made Monster, and The Monster That Challenged the World. He used these scores to almost completely replace the original Japanese score by Akira Ifukube.[28] Beck wanted the film's score to have a more western sound as he thought the original Japanese score sounded too "oriental".[14] Beck also obtained stock footage from the film The Mysterians from RKO (the film's US copyright holder at the time) which he used to not only represent the UN communication satellite but which he also used during the film's climax. Beck was unimpressed with the tiny tremor that occurs in the Japanese version when Kong and Godzilla are fighting underwater. He utilized stock footage of a massive Earthquake from The Mysterians, in order to make the Earthquake much more violent than the tame tremor seen in the Japanese version. This footage features massive tidal waves, flooded valleys, and the ground splitting open swallowing up various huts. None of this over the top carnage is seen in the Japanese version of the film.

Beck spent roughly $15,500 making his English version and sold the film to Universal Pictures International for roughly $200,000 on April 29, 1963.[25]

The English version runs 91 minutes, six minutes shorter than the original Japanese version.

Release

This film was released in Germany as Die Rückkehr des King Kong (The Return of King Kong) and in Italy as Il Trionfo Di King Kong (The Triumph of King Kong)[29][30]

In Japan, this film has the highest box office attendance figures of all of the Godzilla series to date. It sold 11.2 million tickets during its initial theatrical run accumulating ¥350,000,000 in grosses.[13] After 2 theatrical re-releases in 1970 and 1977 respectively, it has a lifetime figure of 12,550,000 tickets sold.

Home Video

The Japanese version of this film was released numerous times through the years by Toho on different home video formats. The film was first released on VHS in 1985 and again in 1991. It was released on Laserdisc in 1986 and 1991, and then again in 1992 as part of a laserdisc box set called the Godzilla Toho Champion Matsuri. Toho then released the film on DVD in 2001. They released it again in 2005 as part of the Godzilla Final Box DVD set,[31] and again in 2010 as part of the Toho Tokusatsu DVD Collection. This release was volume #8 of the series and came packaged with a collectible magazine that featured stills, behind the scenes photos, interviews, and more.

The American version was released on VHS by GoodTimes Entertainment (which acquired the license of some of Universal's film catalogue) in 1987, and then on DVD to commemorate the 35th anniversary of the film's U.S release in 1998. Both these releases were full-frame. Universal Studios itself released the English-language version of the film on DVD in widescreen as part of a 2-pack bundle with King Kong Escapes in 2005.[31]

Preservation

This film is infamous for being one of the most poorly preserved tokusatsu films. In 1970, director Ishiro Honda prepared his edited version of the film for the Champion Matsuri, a film festival that showed edited re-releases of older kaiju films along with cartoons and newer kaiju films aimed at children. Unfortunately, 24 minutes were cut out of the original negative in the process. As a result, the only known sources for these cut portions are copies of the John Beck version for about 15 of the minutes and badly faded 16mm prints for the other 9.[32]

For the film's laserdisc release in 1991, Toho completed a crude reconstruction of the original 1962 version. A 35mm Champion Matsuri copy was used for the majority of the film and the 16mm internegative was spliced in for all the missing portions, sometimes within the same shot as an incomplete Matsuri shot, resulting in missing frames and inconsistent quality. This laserdisc transfer has been the basis for all home video editions of the Japanese version since 1991.[31]

Legacy

The Simpsons pay a pop culture reference to this film, as King Wrong (Homer Simpson) battles Bridezilla (Marge Simpson).

The Simpsons pay a pop culture reference to this film, as King Wrong (Homer Simpson) battles Bridezilla (Marge Simpson).

Due to this film's great box office success, Toho announced plans to do a sequel almost immediately. The sequel was simply called Continuation: King Kong vs. Godzilla.[33] Apparently though, the project never evolved past that announcement.

Also due to the great box office success of this film, Toho was convinced to build a franchise around the character of Godzilla and started producing sequels on a yearly basis. The next project was to pit Godzilla against another famous movie monster icon: a giant version of the Frankenstein monster. In 1963, Kaoru Mabuchi (a.k.a Takeshi Kimura) wrote a script called Frankenshutain tai Gojira.[34] Ultimately, Toho rejected the script and the next year pitted Mothra against Godzilla instead, in the 1964 film Mothra vs. Godzilla. This began an intra-company style crossover where kaiju from other Toho kaiju films would be brought into the Godzilla series.

Toho was eager to build a series around their version of King Kong but were refused by RKO.[35] They worked with the character again in 1967 though, when they helped Rankin/Bass co produce their film King Kong Escapes (which was loosely based on a cartoon series R/B had produced). That film, however, was not a sequel to King Kong vs. Godzilla.

Henry Saperstein (whose company UPA co-produced the 1965 film Frankenstein Conquers the World and the 1966 film War of the Gargantuas with Toho) was so impressed with the octopus sequence that he requested the creature to appear in these two productions. The giant octopus appeared in an alternate ending in Frankenstein Conquers the World that was intended specifically for the American market but was ultimately never used.[34] The creature did reappear at the beginning of the films sequel War of the Gargantuas this time being retained in the finished film.[36]

Even though it was only featured in this one film (although it was used for a couple of brief shots in Mothra vs. Godzilla[37]), this Godzilla suit was always one of the more popular designs among fans from both sides of the Pacific. It formed the basis for some early merchandise in the US in the 1960s, such as a popular model kit by Aurora Plastics Corporation, and a popular board game by Ideal Toys.[38]

The King Kong suit from this film was redressed into the giant monkey Goro for episode 2 (GORO and Goro) of the television show Ultra Q.[39] Afterwards it was reused for the water scenes (although it was given a new mask/head) for the film King Kong Escapes.[40]

Scenes of the giant octopus attack were reused in black and white for episode 23 (Fury of the South Seas) of the television show Ultra Q.[39]

A scene from this film was reused as stock footage in the 1972 film Godzilla vs. Gigan. The scene of the construction vehicles digging the giant pit to trap Godzilla, was reused to portray the construction vehicles building the World Children's Land theme park in Godzilla vs Gigan.[41]

In 1992 (to coincide with the company's 60th anniversary), Toho wanted to remake this film as Godzilla vs. King Kong [42] as part of the Heisei series of Godzilla films. However, according to the late Tomoyuki Tanaka, it proved to be difficult to obtain permission to use King Kong.[43] Next, Toho thought to make Godzilla vs. Mechani-Kong[44] but, (according to Koichi Kawakita), it was discovered that obtaining permission even to use the likeness of King Kong would be difficult.[45][46] Mechani-Kong was replaced by Mechagodzilla, and the project eventually evolved into Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla II in 1993.

The film was referenced in Da Lench Mob's 1992 single "Guerillas in tha Mist".

In Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, the special effects crew was instructed to watch the giant octopus scene to get reference for the Kraken.[47]

King Kong and Godzilla were reunited again in a Bembos burger commercial from Peru.[48]

Dual ending myth

For many years a popular myth has persisted that in the Japanese version of this film, Godzilla emerges as the winner. The myth originated in the pages of Spacemen magazine, a 1960s sister magazine to the influential publication Famous Monsters of Filmland. In an article about the film, it is incorrectly stated that there were two endings and "If you see King Kong vs Godzilla in Japan, Hong Kong or some Oriental sector of the world, Godzilla wins!"[49] The article was reprinted in various issues of Famous Monsters of Filmland in the years following such as issues 51, and 114. This bit of incorrect info would be accepted as fact and persist for decades, transcending the medium and into the mainstream. For example decades later in the 1980s, the myth was still going strong. The Genus III edition of the popular board game Trivial Pursuit had a question that asked "Who wins in the Japanese version of King Kong vs. Godzilla?", and states that the correct answer is "Godzilla". As well, through the years, this myth has been misreported by various members of the media,[50] and has been misreported by reputable news organizations such as The LA Times.[25] Since seeing the original Japanese-language versions of Godzilla movies was very hard to come by from a Western standpoint during this time period, it became easily believable.

However, as more Westerners were able to view the original version of the film (especially after its availability on home video during the late 1980s), and gain access to Japanese publications about the film, the myth was dispelled. There is only one ending of this film. Both versions of the film end the same way: Kong and Godzilla crash into the ocean, and Kong is the only monster to emerge and swims home. The only differences between the two endings of the film are extremely minor and trivial ones:

- In the Japanese version, as Kong and Godzilla are fighting underwater, a very small earthquake occurs. In the American version, producer John Beck used stock footage of a violent earthquake from the film The Mysterians to make the climactic earthquake seem far more violent and destructive.

- The dialogue is slightly different. In the Japanese version onlookers are speculating that Godzilla might be dead as they watch Kong swim home and speculate that it's possible he survived. In the American version, onlookers simply say, "Godzilla has disappeared without a trace" and newly shot scenes of reporter Eric Carter have him watching Kong swim home on a viewscreen and wishing him luck on his long journey home.

- As the film ends and the screen fades to black, owari (the end) appears on screen. Godzilla's roar followed by Kong's is on the Japanese soundtrack. This was akin to the monsters' taking a bow or saying goodbye to the audience, as at this point the film is over. In the American version, only Kong's roar is present on the soundtrack.

References

- ^ "King Kong vs Frankenstein". http://www.kaijuhq.org/unmade18.html.

- ^ Steve Archer. Willis O'Brien: Special Effects Genius. Mcfarland, 1993. Pgs. 80-83

- ^ The 13 Faces of Frankenstein by Forrest J Ackerman. Famous Monsters of Filmland #39. Warren Publishing. 1966. Pgs. 58-60

- ^ Don Glut. The Frankenstein Legend: A Tribute to Mary Shelly and Boris Karloff. Scarecrow Press, 1973. Pgs. 242-244

- ^ Paul A. Woods. King Kong Cometh!. Plexus Publishing Limited, 2005. Pg. 119

- ^ Willis O'Brien-Creator of the Impossible by Don Shay. Cinefex #7 R.B Graphics. 1982. Pgs. 69-70

- ^ Mark Cotta Vaz. Living Dangerously: The Adventures of Merian C Cooper. Villard, 2005. Pgs. 361-363

- ^ A Walk Through Monster Films of the Past by Hiroshi Takeuchi. Markalite-The Magazine of Japanese Fantasy #3. Pacific Rim Publishing Company. 1991. Pgs. 56-57

- ^ a b c Gaisha Kabushiki. Gojira Eiga 40-Nenshi, Gojira Deizu (Godzilla Days: 40 years of Godzilla Movies). Shueisha, 1993. Pgs. 115-123

- ^ Steve Ryfle. Japan's Favourite Mon-Star. ECW Press, 1998. Pg.82

- ^ Peter H. Brothers. Mushroom Clouds and Mushroom Men: The Fantastic Cinema of Ishiro Honda. Author House. 2009. Pg. 14

- ^ Stuart Galbraith IV. Monsters are Attacking Tokyo! Feral House, 1998. Pgs. 83-84

- ^ a b Peter H. Brothers. Pgs. 47-48

- ^ a b August Ragone. Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters. Chronicle Books. 2007. Pg. 70

- ^ "Koichi Takano memoriam on SciFiJapan". http://www.scifijapan.com/articles/2008/12/27/koichi-takano-1935-2008/.

- ^ Sho Motoyama & Rieko Tsuchiya. Godzilla Museum Book. ASCII Publishing, 1994.

- ^ Masumi Kaneko & Shinsuke Nakajima. Gojira Mook (Godzilla Graph Book). Kondansya Publishing, 1983. Pg. 103

- ^ Donald F. Glut. Classic Movie Monsters. Scarecrow Press. 1978.

- ^ Masami Yamada. The Pictorial Book of Godzilla Vol. 2. Hobby Japan Co, Ltd. 1995. Pgs. 46-47

- ^ Masumi Kaneko & Shinsuke Nakajima. Pg.67

- ^ Osamu Kishikawa. Godzilla Second 1962-1964. Dai Nippon Kaiga Co, Ltd. 1994. Pg. 62.

- ^ Osamu Kishikawa.Pg. 63.

- ^ Masami Yamada. Pg. 48

- ^ Toho Company Limited. Toho Films Vol.8. Toho Publishing Co. Ltd, 1963. Pg. 9

- ^ a b c Steve Ryfle. pp. 87–90.

- ^ The Legend of Godzilla-Part One by August Ragone and Guy Tucker. Markalite: The Magazine of Japanese Fantasy #3. Pacific Rim Publishing Company, 1991. Pg. 27

- ^ "Kaijuphile Movie Reviews : King Kong vs. Godzilla". Kaijuphile.com. http://www.kaijuphile.com/rodansroost/movies/kkvg.shtml. Retrieved 2010-05-31.

- ^ War of the Titans (Linear Notes) by David Hirsch. King Kong vs Godzilla: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. La-La Land Records, 2005. Pgs. 4-9

- ^ Godzilla Abroad by J.D Lees. G-Fan #22. Daikaiju Enterprises, 1996. Pgs. 20-21

- ^ "Scans of King Kong vs Godzilla theatrical posters". http://www.fjmovie.com/tposter/60-2/poster60e-2.htm#kkvsg-jp.

- ^ a b c "Complete list of home video releases for King Kong vs Godzilla". http://www.ld-dvd.2-d.jp/gallery2/hikakukingoji.html.

- ^ Steve Ryfle. Pg. 86

- ^ "Continuation King Kong vs Godzilla". http://www.tohokingdom.com/cutting_room/cont_king_kong_vs_godzilla.htm.

- ^ a b "Frankenstein vs. the Giant Devilfish". http://augustragone.blogspot.com/2009/05/frankenstein-vs-giant-devilfish-or.html.

- ^ Ray Morton, King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon, Applause Theater and Cinema Books. 2005. Pgs. 134-135

- ^ Katusnobu Higashino. Toho Kaijuu Gurafitii (Toho Monster Graffiti), Kindai Eigasha. 1991. Pgs. 35-37

- ^ "Evolution of Godzilla". http://www.historyvortex.org/GodzillaEvolution.html.

- ^ "1960s Godzilla board game scan". http://s3.amazonaws.com/boardgamegeek/images/pic153848_sized.jpg.

- ^ a b "The Q-Files". http://www.historyvortex.org/QFiles.html.

- ^ August Ragone, Page. 165

- ^ http://www.tohokingdom.com/movies/godzilla_vs_gigan.htm#stock

- ^ "Godzilla vs. King Kong". http://www.tohokingdom.com/web_pages/lost_projects/godzilla_vs_king_kong91.htm.

- ^ Toho Company Limited, Toho Sf Special Effects Movie Series Vol 8: Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla, Toho Publishing Products Division, 1993

- ^ "Godzilla vs. Mechani-Kong". http://www.tohokingdom.com/web_pages/lost_projects/godzilla_vs_mechani_kong.htm.

- ^ Koichi Kawakita interview by David Milner, Cult Movies #14, Wack "O" Publishing, 1995

- ^ "Koichi Kawakita Interview". http://www.historyvortex.org/KawakitaInterview.html.

- ^ "Behind the Scenes of the Pirates of the Caribbean Movies". http://movies.about.com/od/piratesofthecaribbean2/a/pirates113006_2.htm.

- ^ "King Kong and Godzilla Bembos Burger Commercial". http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GMI6G2nm5i8&feature=related.

- ^ Return of Kong by Forrest J Ackerman. Spacemen #7. Warren Publishing, 1963. Pgs. 52-56

- ^ "Bob Costas misreporting dual ending myth". http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SuL03iluTdA.

External links

- King Kong vs. Godzilla at the Internet Movie Database

- King Kong vs. Godzilla at Rotten Tomatoes

- Archer, Eugene. "King Kong vs. Godzilla" (film review) The New York Times. June 27, 1963.

- "キングコング対ゴジラ (Kingu Kongu tai Gojira)" (in Japanese). Japanese Movie Database. http://www.jmdb.ne.jp/1962/cl002600.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

Categories:- Japanese films

- Godzilla films

- King Kong films

- Kaiju films

- Giant monster films

- Monster movies

- 1962 films

- Crossover films

- American science fiction films

- Japanese-language films

- 1960s science fiction films

- Sequel films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films directed by Ishirō Honda

- Crossover tokusatsu

- Films set in the 1960s

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.