- Mamilla

-

Modern Mamilla; the walls surrounding the Old City of Jerusalem can be seen in the background.

Modern Mamilla; the walls surrounding the Old City of Jerusalem can be seen in the background.

Mamilla (Hebrew: ממילא) was an early neighbourhood constructed outside Jerusalem's Old City west from the Jaffa Gate, and now refers to the $400 million commercial and housing district developed in selected parts of the area.

Mamilla was originally established in the late 19th century as a mixed Jewish-Arab central business district. Between the 1948 Arab-Israeli War and the 1967 Six-Day War, it was located along the armistice line between the Israeli and Jordanian-held sector of the city. It went into decline after many of its buildings were destroyed by Jordanian shelling. After 1967, the government approved an urban renewal project for Mamilla. Land was apportioned to residential and commercial zones, including hotels and office space, in what was to become one of the longest and most costly development plans in the history of modern Jerusalem. Most of the plan was finally realized by the summer of 2007 with the opening of its major mall and entertainment components.

Contents

Etymology

The name Mamilla may be a corruption of the Hebrew word for 'the filler' (m'malle'), though that is uncertain.[1]

According to other sources the word Mamilla probably stems from the Arabic: مأمن الله, meaning "that which comes from God". The name may possibly refer to an early church that existed on the site, or perhaps be connected with a Christian Saint of the same name. The area is home to a Mamluk Mamilla Cemetery of the same name, and in its centre lies Mamilla Pool, one of the three reservoirs constructed by Herod the Great during the 1st century BCE.[2][3]

Geography

The neighbourhood of Mamilla is located within the northwest extension of the Hinnom Valley, which extends from the southwest corner of the Old City along the city's western wall. The neighbourhood is bounded by the Jaffa Gate and Jaffa Road to the east and north, the downtown and Rehavia neighbourhood above it to the west, and Yemin Moshe's upward slope along its southwestern edge. Its total area is 120 dunam (0.12 km², 0.05 mi²).[2][3]

History

Main article: History of JerusalemOttoman control

Theodor Herzl's 1898 visit with a delegation of Zionist leaders.

Theodor Herzl's 1898 visit with a delegation of Zionist leaders.

Prior to construction of the neighbourhood in the late 19th century, the area of Mamilla was empty aside from a few olive trees, and was only notable for the junction of paths that would become Jaffa Road and the highway to Jaffa, with the road to Hebron outside the Jaffa Gate. Among its first structures was the Hospice Saint Vincent de Paul, part of the emerging Jerusalem French Compound.[2]

The early building developed as an extension of the adjacent souk along the city walls at the Jaffa Gate as a quarter for merchants and artisans. It became home for commerce and residences that could not find room within the overcrowded Old City, and several of Jerusalem's prominent modern businesses, like the Hotel Fast, were first built here. The Ottoman authorities lacked urban planning, and their only major contribution to the neighbourhood was the 1908 erection of a clock tower atop Jaffa Gate, which only stood a decade until the 1918 British conquest during World War I.[2][4]

British control

Main article: British Mandate of PalestineThe British arrival in Jerusalem heralded a rational philosophy of infrastructure planning and development. It respected cultural and historic heritage and attempted to preserve such elements within the blossoming construction of the modern city. The city walls were identified as such an element, so British workers acted to clear away the stalls on their perimeter and maintain an open area between the walls and the rest of the New City in the interest of an aesthetically pleasing visual basin. By the same token, planners demolished the Ottoman clock tower to preserve a historic skyline.

Following the approval of the 1947 UN Partition Plan, an Arab mob ransacked and burned much of the district and stabbed some of its Jewish residents in the course of the 1947 Jerusalem riots, one of the events leading to the area's decades-long stagnation.[2][3]

Divided city

As the 1948 Arab-Israeli War commenced, the neighbourhood's location between Israeli and Jordanian forces made it a combat zone, leading to the flight of both Jewish and Arab residents. On May 22, 1948 the US Consul, Thomas C. Wasson, was assassinated shortly ater leaving the French Consulate in the Mamilla district. After the signing of the 1949 Armistice Agreements and division of Jerusalem, the western three-quarters of Mamilla were held by Israel and the eastern quarter became a no man's land of barbed-wire and concrete barricades between Israeli and Jordanian lines. The active and hostile border subjected Mamilla to Jordanian sniper and guerilla attacks, and even stones thrown by Arab Legionnaires from the Old City walls above. The neighbourhood was one of several border areas in the city to experience a sharp decline, and subsequently became home to families of new immigrants with many children and of weak financial abilities, as well as dirty light industry like auto repair.[2][3] In Mamilla in this period, the residents were primarily Kurdish immigrants and their Israeli children.[5]

Reunification

After the 1967 Six-Day War, Israeli authorities expanded the municipality to include the Old City and beyond. They tore down the barricades that had lined Mamilla's 19-year border and restored the connections between the formerly-divided sectors. Many buildings on Mamilla's eastern end were in shambles from the years of fighting as well as from the resultant limitations on maintenance. Several historic buildings had to be condemned. One of these was the Stern House, which housed Zionist leader Theodor Herzl on his 1898 visit. However, popular outcry brought Supreme Court involvement which led to the temporary dismantling and reassembly nearby of this historical landmark.[2][3]

Rehabilitation

The terrace and Jerusalem stone covered parking garage with construction in the background (January 2007).

The terrace and Jerusalem stone covered parking garage with construction in the background (January 2007).

The 1970s saw numerous proposals for rehabilitating the neighbourhood, and it was defined as a zone of high-priority for reconstruction efforts. The administration responsible for preservation and construction in the Old City took Mamilla under its jurisdiction as well, both because of its proximity and its possession of many of the same considerations that the British weighed when regulating its development. A 1972 master-plan for revitalising the city centre transferred 100 of the 120 dunams (0.1 km², 0.04 mi²) to Karta, the municipal firm led by architects Gilbert Weil and Moshe Safdie charged with the project, and called for the destruction of almost every building save the French Hospice Saint Vincent de Paul. The plan called for an underground street system overlaid with mixed-use development, including a pedestrian mall, parking for 1,000 cars, and a bus terminal.[2][3]

This plan evoked massive criticism throughout the city government, although mayor Teddy Kollek lent full political backing to the plan. When deputy mayor Meron Benvenisti commissioned a more conservative plan under architect David Kroyanker based on facadism, the mayor immediately filed it away without any discussion. Karta evicted 700 families, communal institutions, and businesses, placing them in the then-developing neighbourhoods of Baka and Neve Yaakov, and moved the industry to Talpiot, the seed of its current industrial zone. The evictions cost the Israeli government over $60 million and were only completed in 1988, when Mamilla ceased to exist as a neighbourhood and instead became a "compound" slated for future construction.[2][3][6][7]

The evicted residents were mostly Jewish immigrants from Arab states whose weak financial status left them vulnerable to Kollek's plan. The following steep increase in real-estate values of formerly depressed areas like Mamilla near the former armistice line and the Old City was perceived by evicted Mizrahi Jews as an injustice. This became a key issue in 1970s Israeli social upheaval and the founding of the Black Panthers movement in Israel.[8][9]

Rebuilding

After 16 years of controversy, during which half-constructed Mamilla remained an eyesore in the heart of the city, a revised plan drawn up by architect Moshe Safdie incorporating elements of Kroyanker's conservative design moved forward in 1986. The new plan called for the compound to be divided into four areas: a pedestrian mall including a large multi-storey car park and boulevard with mixed-use 3-6 storey buildings, terraced residential buildings on its southern end, and two hotels along its border with the downtown. The British Ladbroke Group plc, which controls the Hilton Hotels Corporation, won the bid to build the project's main hotel (originally Hilton Jerusalem and now David Citadel Hotel) and its housing, which it built as a luxury gated community named David's Village.[2][3][10][11][12]

Numerous disputes between Karta and Ladbroke led the British firm to exit the project, and its shares were assumed by Alfred Akirov's Alrov company. However, further objections from many sources—including religious groups opposed to an entertainment area so close to the Old City and possible operation on the Jewish Sabbath—kept construction at a crawl. Both Alrov and Karta accused each other of breach of contract and sued. After years of frozen construction and drawn-out mediation, the Jerusalem district court found parts of both parties' complaints to be justified and ordered 100 million NIS paid to Alrov by Karta, which allowed construction to resume.

May 28, 2007 saw the opening of phase one of the shopping mall and part of the 600-meter promenade. The completion of the remainder of the promenade, the Stern House rebuilding, and the other construction, including the 207-room five-star second hotel, is scheduled to be completed in the spring of 2008.[2][3][11][12]

Like several other luxury neighbourhoods in the city, apartments in the David's Village development are mostly owned by foreigners who visit for only a few days or weeks a year. Critics contend that this makes it a ghost town in the city centre.

Mamilla is also the location of the projected Simon Wiesenthal Center's Center for Human Dignity, a controversial project because its construction would require building on an old Muslim cemetery.[10][13]

Shopping mall

Main article: Mamilla Mall Old city walls and mamilla ave. at night - as seen from "Rooftop" restaurant on the roof of Mamilla Hotel. October 2011

Old city walls and mamilla ave. at night - as seen from "Rooftop" restaurant on the roof of Mamilla Hotel. October 2011

The $150 million, pedestrian-only Mamilla shopping mall has been touted as a luxury destination in the style of Los Angeles' Rodeo Drive or The Grove. Its commercial space is leased at $40 to $80 per square metre to 140 businesses, including international names like Rolex, MAC, H. Stern, Nike, Polo Ralph Lauren, Nautica, bebe, and Tommy Hilfiger, as well as local chains like Castro, Ronen Chen, Steimatzky Books, and Cafe Rimon. The mall is also slated to house an IMAX theatre.[11][12] The first Gap store in Israel opened in Mamilla mall in fall 2009.

Notable residents

- Uri Malmilian (born 1957), football (soccer) player and manager

References

- ^ A history of Jerusalem, John Gray, Praeger, 1969, p. 49

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Gil Zohar (May 24, 2007). "Long-awaited luxury". The Jerusalem Post. http://fr.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1178708673954&pagename=JPost/JPArticle/ShowFull.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Schwiki, Itzik (February 8, 2005). "The Total Experience from Dismantling and Rebuilding Teaches that This is a Highly Dubious Way of Preservation". 02net. http://www.02net.co.il/Site/Templates/inPage.asp?catID=5&subID=453&docID=13100. Retrieved 2007-07-20. (Hebrew)

- ^ Oren-Nordheim, Michael; Oren-Nordheim (2001). Jerusalem and Its Environs: Quarters, Neighborhoods, Villages, 1800-1948. Wayne State University Press. p. 408. ISBN 0814329098. http://books.google.com/books?id=KzOAxmHDzHUC&pg=PA34&lpg=PA34&dq=jaffa+gate+clocktower&source=web&ots=l3sUqoLmYo&sig=yk6goW23LBx9DennSQYXtjv9yuA#PPA34,M1.

- ^ From prosperity to decay and back again, Jerusalem Post, Aug. 27, 2009, Peggy Cidor [1]

- ^ David Kroyanker (April 1, 2007). "Heart and soul of Jerusalem". Haaretz. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/objects/pages/PrintArticleEn.jhtml?itemNo=809721. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ^ Loury, Aviva (January 1, 2007). "Anger of an Architect". Haaretz. http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/pages/ShArtPE.jhtml?itemNo=811904&contrassID=2&subContrassID=13&sbSubContrassID=0. Retrieved 2007-07-20.(Hebrew)

- ^ שיר-לי גולן (July 8, 2007). "הם כן נחמדים". Ynet. http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-3422297,00.html. Retrieved 2007-07-20.(Hebrew)

- ^ Mizrahi, Iris (March 16, 2001). "30 Years to the Campaign of the Black Panthers". Kedma. http://www.kedma.co.il/Panterim/GodWithThePanterim_Mizrahi.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-20. (Hebrew)

- ^ a b Kroyanker, David (2007). "Next Year, in the Rebuilt Mamilla". Haaretz. http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasite/pages/ShArtPE.jhtml?itemNo=697723&contrassID=2&subContrassID=2&sbSubContrassID=0. Retrieved 2007-07-20.(Hebrew)

- ^ a b c Orit Arfa (June 8, 2007). "History and trends blend in Jerusalem as deluxe mixed-use center opens in historic area". Jewish Journal. http://www.jewishjournal.com/home/preview.php?id=17776. (video tour)

- ^ a b c "Ambitious hotel-shopping complex going up in Jerusalem". j.. May 25, 2007. http://www.jewishsf.com/content/2-0-/module/displaystory/story_id/32620/format/html/displaystory.html.

- ^ Lori Lowenthal Marcus (February 28, 2006). "A faux controversy - and ironic too". The Jerusalem Post. p. 15.

Further reading

- Mamilla: Prosperity, Decay and Renewal - the Alrov Mamilla Quarter, by David Kroyanker, Keter pub. 2009

- "Grand Opening of Jerusalem's Mamilla Alrov Quarter Promenade". 5 Towns Jewish Times. June 7, 2007. http://www.5tjt.com/news/read.asp?Id=1239.

- Ofer Petersburg (May 21, 2007). "Jerusalem flat sold for record $9 million". Ynet. http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3402690,00.html.

- Greer Fay Cashman (June 20, 2006). "Business Scene". The Jerusalem Post. p. 18.

- Gail Lichtman (September 2, 2005). "Mamilla Blues". The Jerusalem Post. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-113409722.html.

- Human Skeletal Remains from the Mamilla cave, Jerusalem

- Encounters- David-s Village- Mamilla Jerusalem Foreign Ministry of Israel

- "Mamilla sales reach $21.4 million. (Jerusalem Development (Mamilla) Company Ltd.)". Israel Business Today. December 6, 1991. http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-11844259.html.

External links

- Mamilla Campaign

- Mamilla-Alrov quarter official website

- Mamilla-Alrov quarter HD Virtual tour

- Israel Shamir: Mamilla Pool

- Mamilla Hotel Jerusalem

- Alrov Mamilla Avenue

- Mamilla Project at the LCUD site

Neighborhoods of Jerusalem Old City East Jerusalem American Colony • Al Bustan • Al-Issawiya • At-Tur • Bab a-Zahara • Beit Hanina • Jabel Mukaber • Ma'ale ha-Zeitim • Nachalat Shimon • Nof Zion • Ras al-Amud • Sheikh Jarrah • Shimon HaTzadik • Shuafat • Silwan • Sur Baher • Umm Tuba • Wadi al-JozHaredi neighborhoods Batei Munkatch • Batei Ungarin • Beit Yisrael • Ezrat Torah • Geula • Givat Shaul • Har Nof • Kerem Avraham • Kiryat Belz • Kiryat Mattersdorf • Kiryat Sanz • Kiryat Shomrei Emunim • Machanayim • Mea Shearim • Mekor Baruch • Nachalat Ya'akov • Ramat Shlomo • Ramot Polin • Sanhedria • Sanhedria Murhevet • Sha'arei Hesed • Shmuel HaNavi • Tel Arza • Unsdorf • Zikhron MosheCentral Neighborhoods Batei Nissan Bak • Beit David • Beit Ya'akov • Bukharan neighborhood • Even Yisrael • Ezrat Yisrael • Givat Ram • Katamon • Kiryat Shmuel • Kiryat Wolfson • Mahane Israel • Mahane Yehuda • Merhavia • Mishkenot Sha'ananim • Musrara • Nachalat Achim • Nachlaot • Nayot • Neve Sha'anan • Ohel Shlomo • Rehavia • Yemin MosheNorthern Neighborhoods French Hill • Givat HaMivtar • Ma'alot Dafna • Neve Yaakov • Pisgat Ze'ev • Ramat Eshkol • Ramot • Ramot PolinSouthern Neighborhoods Abu Tor • Baka • Beit Safafa • East Talpiot • The German Colony • Gilo • Givat HaMatos • Greek colony • Har Homa • Mekor Chaim • Ramat Rachel • TalpiotWestern Neighborhoods Bayit VeGan • Beit HaKerem • Givat Massuah • Givat Mordechai • Givat Oranim • Har Hotzvim • Ir Ganim • Katamonim • Kiryat HaYovel • Kiryat Menachem • Kiryat Moshe • Malha • Motza • Pat • Ramat Beit HaKerem • Ramat Denya • Ramat Sharett • Romema • Yefeh NofHistoric Neighborhoods See also: Ring NeighborhoodsCoordinates: 31°46′34.02″N 35°13′24.44″E / 31.7761167°N 35.2234556°E

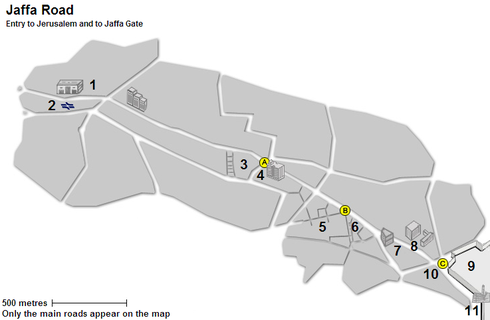

Jaffa Road Places 1. Central Bus Station · 2. Railway station (planned) · 3. Mahane Yehuda Market · 4. Klal Center

5. Ben Yehuda Street · 6. Nahalat Shiva · 7. Generali Building · 8. Safra Square / City Hall · 9. Old City

10. Mamilla · 11. Jaffa Gate / Tower of DavidSquares A. Davidka Square · B. Zion Square · C. Tzahal Square · D. Safra Square Categories:- Neighbourhoods of Jerusalem

- Central business districts

- Planned developments

- Gated communities

- Shopping malls in Israel

- Populated places established in the 19th century

- Shopping malls established in 2007

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.