- Achillea millefolium

-

Achillea millefolium

near Amiens, France Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae (unranked): Angiosperms (unranked): Eudicots (unranked): Asterids Order: Asterales Family: Asteraceae Genus: Achillea Species: A. millefolium Binomial name Achillea millefolium

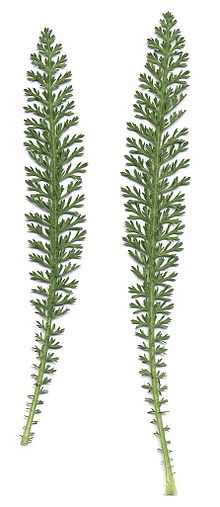

L.Achillea millefolium or yarrow is a flowering plant in the family Asteraceae, native to the Northern Hemisphere.[1] In New Mexico and southern Colorado, it is called plumajillo, or "little feather", for the shape of the leaves. In antiquity, yarrow was known as herbal militaris, for its use in staunching the flow of blood from wounds.[2] Other common names for this species include common yarrow, gordaldo, nosebleed plant, old man's pepper, devil's nettle, sanguinary, milfoil, soldier's woundwort, thousand-leaf (as its binomial name affirms), and thousand-seal.

Contents

Description

Common yarrow is an erect herbaceous perennial plant that produces one to several stems (0.2 to 1m tall) and has a rhizomatous growth form. Leaves are evenly distributed along the stem, with the leaves near the middle and bottom of the stem being the largest. The leaves have varying degrees of hairiness (pubescence). The leaves are 5–20 cm long, bipinnate or tripinnate, almost feathery, and arranged spirally on the stems. The leaves are cauline and more or less clasping. The inflorescence has 4 to 9 phyllaries and contains ray and disk flowers which are white to pink. There are generally 3 to 8 ray flowers that are ovate to round. Disk flowers range from 15 to 40. The inflorescence is produced in a flat-topped cluster. The fruits are small achenes. Yarrow grows at low or high altitudes, up to 3500m above sea level. The plant commonly flowers from May through June, and is a frequent component in butterfly gardens. Common yarrow is frequently found in the mildly disturbed soil of grasslands and open forests. Active growth occurs in the spring.[1]

In North America, there are both native and introduced genotypes, and both diploid and polyploid plants.[3] The plant has a strong, sweet scent, similar to chrysanthemums.[1]

Establishment

Common yarrow is a drought tolerant species of which there are several different ornamental cultivars. Seeds require light for germination, so optimal germination occurs when planted no deeper than ¼ inch (~6 mm). Seeds also require a germination temperature of 18–24 °C (64–75 °F). Common yarrow responds best to soil that is poorly developed and well drained. The plant has a relatively short life, but may be prolonged by dividing the plant every other year, and planting 12 to 18 inches (30–46 cm) apart. Common yarrow is a weedy species and can become invasive.[4] It may suffer from mildew or root rot if not planted in well-drained soil.

There are several varieties and subspecies:

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. millefolium - Europe, Asia

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. alpicola - Rocky Mountains

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. borealis - Arctic regions

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. californica - California

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. occidentalis - North America

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. pacifica - west coast of North America

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. puberula - California

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium var. rubra - Southern Appalachians

- Achillea millefolium subsp. chitralensis - western Himalaya

- Achillea millefolium subsp. sudetica - Alps, Carpathians

Cultivation and uses

Yarrows can be planted to combat soil erosion due to the plant's resistance to drought.

The herb is purported to be a diaphoretic, astringent,[5] tonic,[5] stimulant and mild aromatic. It contains isovaleric acid, salicylic acid, asparagin, sterols, flavonoids, bitters, tannins, and coumarins. The plant also has a long history as a powerful 'healing herb' used topically for wounds, cuts and abrasions. The genus name Achillea is derived from mythical Greek character, Achilles,[5] who reportedly carried it with his army to treat battle wounds. This medicinal action is also reflected in some of the common names mentioned below, such as Staunchweed and Soldier's Woundwort.[1]

The stalks of yarrow are dried and used as a randomising agent in I Ching divination.

In the Middle Ages, yarrow was part of a herbal mixture known as gruit used in the flavouring of beer prior to the use of hops.[citation needed] The flowers and leaves are used in making some liquors and bitters.[1]

Old folk names for yarrow include arrowroot, bad man's plaything, carpenter's weed, death flower, devil's nettle, eerie, field hops, gearwe, hundred leaved grass, knight's milefoil, knyghten, milefolium, milfoil, millefoil, noble yarrow, nosebleed, old man's mustard, old man's pepper, sanguinary, seven year's love, snake's grass, soldier, soldier's woundwort, stanch weed, thousand seal, woundwort, yarroway, yerw.

The English name yarrow comes from the Saxon (Old English) word gearwe, which is related to both the Dutch word gerw and the Old High German word garawa.[6]

Yarrow has also been used as a food, and was very popular as a vegetable in the seventeenth century. The younger leaves are said to be a pleasant leaf vegetable when cooked as spinach, or in a soup. Yarrow is sweet with a slight bitter taste. The leaves can also be dried and used as a herb in cooking.

Cultivars

The species is generally too weedy for gardens but cultivars include 'Paprika', 'Cerise Queen' and 'Red Beauty'; and the many hybrids of this species designated Achillea x taygetea including 'Appleblossom', 'Fanal' and 'Hoffnung' are useful garden subjects.[7]

Agricultural Use: before the arrival of monocultures of Ryegrass, both grass leys and permanent pasture always contained Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) at a rate of ca. 0.3 kg/ha. At least one of the reasons for Yarrow's inclusion in grass mixtures was that it is a deep rooted herb, whose leaves are rich in minerals. Thus its inclusion helped to prevent mineral deficiencies in the ruminants to whom it was fed.

Herbal medicine

Yarrow has seen historical use as a medicine, often because of its astringent effects.[1] Decoctions have been used to treat inflammations, such as hemorrhoids, and headaches. Confusingly, it has been said to both stop bleeding and promote it. (Depending on the form it is administered it can do both, which is why when dabbling in using herbs for medicine it is proper to contact a herbalist or other expert. Achillea Millefolium has been used with great success in promoting blood flow, as well as staunching blood flow when properly used.)[citation needed] Infusions of yarrow, taken either internally or externally, are said[by whom?] to speed recovery from severe bruising. The most medicinally active part of the plant is the flowering tops. They also have a mild stimulant effect, and have been used as a snuff. Today, yarrow is valued mainly for its action[clarification needed] in colds and influenza, and also for its effect on the circulatory, digestive, excretory, and urinary systems. In the nineteenth century, yarrow was said to have a greater number of indications than any other herb.[citation needed]

It is believed[by whom?] that anti-allergenic compounds can be extracted from the flowers by steam distillation. The flowers are used to treat various allergic mucus problems, including hay fever. Flowers used in this way are harvested in summer or autumn, and an infusion drunk for upper respiratory phlegm or used externally as a wash for eczema.[citation needed]

The dark blue essential oil, extracted by steam distillation of the flowers, is generally used as an anti-inflammatory[8] or in chest rubs for colds and influenza. For a massage oil for inflamed joints, dilute 5-10 drops yarrow oil in 25 ml infused St. John's wort oil. A chest rub can be made for chesty colds and influenza. Combine yarrow with eucalyptus, peppermint, hyssop, or thyme oil, diluting a total of 20 drops of oil in 25 ml almond or sunflower oil.[9]

The leaves encourage clotting, so it can be used fresh for nosebleeds.[10] The aerial parts of the plant are used for phlegm conditions, as a bitter digestive tonic to encourage bile flow, and as a diuretic.[11] The aerial parts act as a tonic for the blood, stimulate the circulation, and can be used for high blood pressure. Also useful in menstrual disorders, and as an effective sweating remedy to bring down fevers.[1]

Yarrow intensifies the medicinal action of other herbs taken with it,[12] and helps eliminate toxins from the body[citation needed]. It is reported[13] to be associated with the treatment of the following ailments:

Analgesic[14] Amenorrhea, antiphlogistic,[15][16] anti-inflammatory, bowels, bleeding, blood clots, blood pressure (lowers), blood purifier, blood vessels (tones), catarrh (acute, repertory), colds, chicken pox, circulation, contraceptive (unproven), cystitis, diabetes treatment, digestion (stimulates)gastro-intestinal disorders,[15] choleretic [17] dyspepsia, eczema, fevers, flu, gastritis, glandular system, gum ailments, heartbeat (slow), influenza, insect repellant, inflammation,[18] emmenagogue,[19] internal bleeding, liver (stimulates and regulates), lungs (hemorrhage), measles, menses (suppressed), menorrhagia, menstruation (regulates, relieves pain), nipples (soreness), nosebleeds, piles (bleeding), smallpox, stomach sickness, toothache, thrombosis, ulcers, urinary antiseptic, uterus (tighten and contract),gastroprotective [20] varicose veins, vision, may reduce autoimmune responses.[21]

The salicylic acid derivatives are a component of aspirin, which may account for its use in treating fevers and reducing pain.[citation needed]

Yarrow was also used in traditional Native American herbal medicine. Navajo Indians considered it to be a "life medicine", chewed it for toothaches, and poured an infusion into ears for earaches. Several tribes of the Plains region of the United States used common yarrow. The Pawnee used the stalk for pain relief. The Chippewa used the leaves for headaches by inhaling it in a steam. They also chewed the roots and applied the saliva to their appendages as a stimulant. The Cherokee drank a tea of common yarrow to reduce fever and aid in restful sleep.[citation needed]

Companion planting

Yarrow is considered an especially useful companion plant, not only repelling some bad insects while attracting good, predatory ones, but also improving soil quality.[citation needed] It attracts predatory wasps, which drink the nectar and then use insect pests as food for their larvae. Similarly, it attracts ladybugs and hoverflies. Its leaves are thought to be good fertilizer, and a beneficial additive for compost.

It is also considered directly beneficial to other plants, improving the health of sick plants when grown near them.[citation needed]

Use by birds

Several cavity-nesting birds, including the common starling, use yarrow to line their nests. Experiments conducted on the tree swallow, which does not use yarrow, suggest that adding yarrow to nests inhibits the growth of parasites.[22]

Insecticidal (EO on larvae of the Culicidae mosquito Aedes albopictus)[23]

Dangers

In rare cases, yarrow can cause severe allergic skin rashes; prolonged use can increase the skin's photosensitivity.[24] This can be triggered initially when wet skin comes into contact with cut grass and yarrow together.

In one study aqueous extracts of yarrow impaired the sperm production of laboratory rats.[25]

History

Yarrow was one herb identified at Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal flower burial of northern Iraq, dated c.60,000BCE along with a number of other medicinal herbs.

In popular culture

Stories about yarrow feature in traditional Chinese culture. For example, it is said that it grows around the grave of Confucius. Also the most authentic way to cast the Yi Jing is to use dried yarrow stalks. The stems are said to be good for divining the future. Chinese proverbs claim that yarrow brightens the eyes and promotes intelligence. Yarrow and tortoiseshell are considered to be lucky in Chinese tradition.[26] Oriental tradition also assured mountain wanderers that where the yarrow grew neither tigers nor wolves nor poisonous plants would be found.

In Classical tradition, Homer tells us that the centaur Chiron, who conveyed herbal secrets to his human pupils, taught Achilles to use yarrow on the battle grounds of Troy.[27] Achilles is said to have used it to stop the bleeding wounds of his soldiers. For centuries it has been carried in battle because of its magical as well as medicinal properties. Western European tradition also connects yarrow with a goddess and a demon. Yarrow was a witching herb, used to summon the devil or drive him away. But it was also a loving herb in the domain of Aphrodite.

Yarrow also featured in British folk customs and beliefs. Yarrow was one of the herbs put in Saxon amulets. These amulets were for protection from everything from blindness to barking dogs. In the Middle Ages, witches were said to use yarrow to make incantations. This may be the source for the common names devil's nettle, devil's plaything, and bad man's plaything. Some people believed that you could determine the devotion of a lover by poking a yarrow leaf up your nostril and twitching the leaf while saying, "Yarroway, yarroway, bear a white blow: if my love loves me, my nose will bleed now". (Yarrow is a nasal irritant, and generally causes the nose to bleed if inserted.) Nursery rhymes say if you put a yarrow sachet under your pillow, you will dream of your own true love. If you dream of cabbages (the leaves do have a similar scent), then death or other serious misfortune will strike. A folk belief states that if you hang a bunch of dried yarrow or yarrow that had been used in wedding decorations over the bed, you can thus ensure a lasting love for at least seven years.

In literature, in the book The Glass Bead Game by Hermann Hesse, Elder Brother uses yarrow stalks to divine the will of the Oracle.

In the science-fiction/fantasy novel Crystal Singer by Anne McCaffrey, Yarrow (or Yarra) is mentioned as the name of a planet where 'the best beer in the galaxy' is brewed.

In the manga and anime series Bleach, the insignia for the Eleventh Division is the Yarrow; the meaning behind it is Fight.

Similar species

Other plants with white flowers in large compound umbels that may be confused with Achillea millefolium include: water parsnip, (swamp parsnip, sium suave) and western water hemlock, (Cicuta douglasii, poison hemlock) and spotted water hemlock (Cicuta maculata, spotted water hemlock, spotted parsley, spotted cowbane). Water parsnip and water hemlock have clusters of small white flowers that are shaped like umbrellas, both grow in moist soils. Water parsnip leaves are once compound, and water hemlock leaves are three times compound. Water hemlock has a large swelling at the stem base. All parts of water hemlock are highly poisonous.[28] Other yarrow species have similar foliage and flowers, including: Achillea ageratifolia and Achillea nobilis.

Gallery

-

Yarrow at BioTrek, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

See also

- List of companion plants

- Sacred herbs

- Flora of South Georgia

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Gualtiero Simonetti (1990). Stanley Schuler. ed. Simon & Schuster's Guide to Herbs and Spices. Simon & Schuster, Inc. ISBN 0-671-73489-X.

- ^ Dodson & Dunmire, 2007, Mountain Wildfowers of the Southern Rockies, UNM Press, ISBN 978-0-8263-4244-7

- ^ Alan S. Weakley (April 2008). "Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, and Surrounding Areas". http://www.herbarium.unc.edu/flora.htm.

- ^ USDA, NRCS. 2006. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 22 May 2006). National Plant Data Center, Baton Rouge, LA 70874-4490 USA.[1]

- ^ a b c Alma R. Hutchens (1973). Indian Herbology of North America. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 0-87773-639-1.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. Yarrow.

- ^ Clausen, Ruth Rogers; Ekstrom, Nicolas H. (1989). Perennials for American gardens. New York: Random House. pp. 4. ISBN 0-394-55740-9.

- ^ Inhibitory effect of lactone fractions and individual components from three species of the Achillea millefolium complex of Bulgarian origin on the human neutrophils respiratory burst activity Choudhary M.I., Jalil S., Todorova M., Trendafilova A., Mikhova B., Duddeck H. Natural Product Research 2007 21:11 (1032-1036)

- ^ Teresa Skwarek (1979). "Effects of Herbal Preparations on the propagation of influenza viruses". Acta Polon Pharm XXXVI (5): 1–7.

- ^ The Southwest School of Botanical Medicine. Specific Indications in Clinical Practice.

- ^ Combining Western Herbs and Chinese Medicine (book), 2003, "Achillea", P.165-181. Jeremy Ross. ISBN 978-0-9728193-0-5.

- ^ Rodale's Illustrated Encyclopedia of Herbs, Kowalchik C & Hylton WH, Eds, "Companion Planting", P.108. ISBN 978-0-87596-964-0.

- ^ Rodale's Illustrated Encyclopedia of Herbs, Kowalchik C & Hylton WH, Eds, P.293, 367, 518. ISBN 978-0-87596-964-0

- ^ Analgesic Effect of aqueous extract of Achillea millefolium L. on rat's formalin test Noureddini M., Rasta V.-R. Pharmacologyonline 2008 3 (659-664)

- ^ a b Benedek, Birgit; Kopp, Brigitte (2007). "Achillea millefolium L. S.l. Revisited: Recent findings confirm the traditional use". Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift 157 (13–14): 312–314. doi:10.1007/s10354-007-0431-9. PMID 17704978.

- ^ Aqueous extract of Achillea millefolium L. (Asteraceae) inflorescences suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in RAW 264.7 murine macrophages Burk D.R., Cichacz Z.A., Daskalova S.M. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research 2010 4:3 (225-234)

- ^ Choleretic effects of yarrow (Achillea millefolium s.l.) in the isolated perfused rat liver Benedek B., Geisz N., Jäger W., Thalhammer T., Kopp B. Phytomedicine 2006 13:9-10 (702-706)

- ^ Effects of two Achillea species tinctures on experimental acute inflammation Popovici M., Pârvu A.E., Oniga I., Toiu A., Tǎmaş M., Benedec D. Farmacia 2008 56:1 (15-23)

- ^ In vitro estrogenic activity of Achillea millefolium L. Innocenti G., Vegeto E., Dall'Acqua S., Ciana P., Giorgetti M., Agradi E., Sozzi A., Fico G., Tomè F. Phytomedicine 2007 14:2-3 (147-152)

- ^ Antiulcerogenic activity of hydroalcoholic extract of Achillea millefolium L.: Involvement of the antioxidant system Potrich F.B., Allemand A., da Silva L.M., dos Santos A.C., Baggio C.H., Freitas C.S., Mendes D.A.G.B., Andre E., de Paula Werner M.F., Marques M.C.A. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2010 130:1 (85-92)

- ^ Aqueous extracts from bogbean and yarrow affect stimulation of human dendritic cells and their activation of allogeneic CD4+ T cells In Vitro Jonsdottir G., Hardardottir I., Omarsdottir S., Vikingsson A., Freysdottir J. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology 2010 71:6 (505)

- ^ Shutler D, Campbell AA (2007). "Experimental addition of greenery reduces flea loads in nests of a non-greenery using species, the tree swallow Tachycineta bicolor". Journal of Avian Biology 38 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.04015.x. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.04015.x.

- ^ Essential oil composition and larvicidal activity of six Mediterranean aromatic plants against the mosquito Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) Conti B., Canale A., Bertoli A., Gozzini F., Pistelli L. Parasitology Research 2010 107:6 (1455-1461)

- ^ Contact Dermatitis 1998, 39:271-272.

- ^ Dalsenter P, Cavalcanti A, Andrade A, Araújo S, Marques M (2004). "Reproductive evaluation of aqueous crude extract of Achillea millefolium L. (Asteraceae) in Wistar rats". Reprod Toxicol 18 (6): 819–23. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2004.04.011. PMID 15279880.

- ^ Chinese Superstitions

- ^ Homer. Iliad. pp. 11.828–11.832.

- ^ "Cicuta maculata". http://www.em.ca/garden/native/nat_cicuta_maculata.html.

Further reading

- Blanchan, Neltje (2005). Wild Flowers Worth Knowing. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.

- Wood, John (2006). Hardy Perennials and Old Fashioned Flowers. Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.

- Hickman, James C., ed (1993). The Jepson Manual: Higher plants of California. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press.

External links

- Achillea millefolium at Kansas Wildflowers

- Achillea millefolium (Dr. Duke's Databases)

- Winter ID pictures

Categories:- Flora of California

- Flora of North Dakota

- Flora of Ohio

- Flora of Estonia

- Flora of Russia

- Flora of Alabama

- Flora of Florida

- Flora of the United Kingdom

- Garden plants

- Drought-tolerant plants

- Herbs

- Lawn weeds

- Leaf vegetables

- Medicinal plants

- Achillea

- Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.