- List of crimes involving radioactive substances

-

This is a list of criminal (or arguably, allegedly, or potentially criminal) acts involving radioactive substances. Inclusion in this list does not necessarily imply that anyone involved was guilty of a crime.

Contents

Use of alpha emitters for murder/attempted murder

Two well known cases exist. In Germany, a man attempted to murder a woman with plutonium. In 2006, former KGB officer Alexander Litvinenko was killed in London by persons unknown (as of 2006) using the short-lived alpha emitter polonium-210.

Plutonium

In the German case, a man attempted to poison his ex-wife with plutonium stolen from WAK (Wiederaufbereitungsanlage Karlsruhe), a small scale reprocessing plant where he worked. He did not steal a large amount of plutonium, just some rags used for wiping surfaces and a small amount of liquid waste. The man was eventually sent to prison.[1][2] At least two people (besides the criminal) were contaminated by the plutonium.[3] Two flats in Landau in the Rhineland-Palatinate were contaminated, and had to be cleaned at a cost of two million euro.[4] Photographs of the case and details of other nuclear crimes have been presented by a worker at the Institute for Transuranium Elements.[5]

A review of the forensic matters associated with stolen plutonium has been published.[6]

The Litvinenko murder

During Litvinenko's medical treatment more than one hypothesis existed as to the cause of Litvinenko's ill health. The first theory was that it was a normal case of thallium poisoning. Later, it was suggested that a radioactive isotope of thallium had been used. The third and final hypothesis (following Litvinenko's death) was that he had been poisoned with a radioactive isotope of polonium. All the evidence now indicates that Russian-made polonium was used to kill Litvinenko.

Radioactive thallium

It was then suggested that a radioactive isotope of thallium might have been used.[7]

Thallium, in large amount, can be a poison in itself, whether radioactive or not. The 201Tl isotope of thallium, in trace amounts, is used routinely around the world for medical procedures such as myocardial scintigraphy.

Dr. Amit Nathwani, one of Litvinenko's physicians, reported: "His symptoms are slightly odd for thallium poisoning, and the chemical levels of thallium we were able to detect are not the kind of levels you'd see in toxicity."[8] Hours before his death, three unidentified circular-shaped objects were found in his stomach via an X-ray scan.[9] It is thought these objects were almost certainly shadows caused by the presence of Prussian blue, the treatment he had been given for thallium poisoning.[10]

Following a deterioration of his condition on 20 November, Litvinenko was moved into intensive care. It was reported that his doctors had given him a 50/50 chance of survival over the three- to four-week period following the poisoning.[11]

News reports at this stage kept an open mind on the cause of Litvinenko's condition, with Scotland Yard considering whether the poison could have been self-administered.[12]

Polonium-210

Shortly after his death, the BBC reported that preliminary tests on the body of Alexander Litvinenko have indicated that he was poisoned with the radioactive isotope polonium-210 which was most likely inhaled or ingested, and traces of which were found at three London locations: in his Muswell Hill home, at a hotel in Grosvenor Square, and at the sushi restaurant where he had met Mario Scaramella.[13][14]

The UK's Health Protection Agency confirmed that they were investigating the risks to people who have been in contact with him.[15]

Details of the radiological threat posed by polonium-210

At a committed effective dose equivalent (CEDE) of 5.14×10−7 sieverts per becquerel (1.9×103 mrem/µCi) for ingested 210Po and a specific activity of 1.66×1014 Bq/g (4.49×103 Ci/g)[16] the amount of material required to produce a lethal dose of radiation poisoning would be only about 0.12 micrograms (1.17×10−7g). The CEDE is normally used for expressing how likely internal exposure is to cause cancer, as the effective half life in humans of polonium is 37 days and the time between the poisoning and the death was short then the dose suffered by Alexander Litvinenko per unit of activity would have been lower than the CEDE. The biological halflife is 30 to 50 days in humans.[17]

Criminal use of X-ray equipment and other radiation technology by secret police

Some former East German dissidents claim that the Stasi used X-ray equipment to induce cancer in political prisoners.[18]

Similarly, some anti-Castro activists claim that the Cuban secret police sometimes used radioactive isotopes to induce cancer in "adversaries they wished to destroy with as little notice as possible".[19] In 1997, the Cuban expatriate columnist Carlos Alberto Montaner called this method "the Bulgarian Treatment", after its alleged use by the Bulgarian secret police.[20]

Atomic spies

A number of people have been arrested and convicted of spying with regards to nuclear matters. For example see the cases of Klaus Fuchs, Theodore Hall, David Greenglass, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, Harry Gold, Mordechai Vanunu and Wen Ho Lee.

Improper transport

The transport of radioactive materials is controlled by a series of criminal laws and is also covered by civil law. In several cases radioactive materials have been transported incorrectly, leading to exposure (or potential exposure) of humans to radiation.

The bus and the radiography set

Transport accidents can cause a release of radioactivity resulting in contamination or shielding to be damaged resulting in direct irradiation. In Cochabamba a defective gamma radiography set containing a iridium-192 source was transported in a passenger bus as cargo.[21] The gamma source was outside the shielding, and it irradiated some bus passengers. The dose suffered by the passengers was initially estimated as being between 20 mGy and 2.77 Gy (Gy = Gray (unit)), but when the accident was reconstructed by placing dosimeters on seats before placing a similar radiography source in the cargo hold of the bus, the dose estimated by this experiment was no more than 500 mGy for the most exposed passenger.

As an indication of what these doses mean, the LD50 (lethal dose for 50% of subjects) in men is ~4 Gy in a single dose. However, doses can reach as high as 80 Gy if administered fractionally over several days (as in radiotherapy treatments where doses are often delivered in fractions of 1 or 2 Gy/day).

AEA technology and the medical source

March 11, 2002 – A 2.5 tonne radio therapy machine containing a 60Co gamma source was transported from Cookridge Hospital, Leeds, England, to Sellafield with defective shielding (a hole should have had a bolt-like plug screwed into it, but it was left open). As the gamma ray beam passing through the hole was directed from the package downwards into the ground, it is not thought that this event caused any injury or disease in either a human or an animal. This event was treated in a serious manner because the defense in depth type of protection for the source had been eroded. If the container had been tipped over in a road crash then a strong beam of gamma rays would have been directed in a direction where it would be likely to irradiate humans. The company responsible for the transport of the source, AEA Technology plc, was fined £250,000 by a British court.

Trafficking in radioactive and nuclear materials

Information reported to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) shows "a persistent problem with the illicit trafficking in nuclear and other radioactive materials, thefts, losses and other unauthorized activities".[22]

From 1993 to 2006, the IAEA confirmed 1080 illicit trafficking incidents reported by participating countries. Of the 1080 confirmed incidents, 275 incidents involved unauthorized possession and related criminal activity, 332 incidents involved theft or loss of nuclear or other radioactive materials, 398 incidents involved other unauthorized activities, and in 75 incidents the reported information was not sufficient to determine the category of incident. Several hundred additional incidents have been reported in various open sources, but are not yet confirmed.[22]

Quack medicine

In the early 20th century a series of "medical" products which contained radioactive elements were marketed to the general public. These are included in this discussion of nuclear/radioactive crime because the sale and production of these products is now covered by criminal law. Because some perfectly good radioactive medical products exist, (such as iodine-131 for the treatment of cancer), it is important to note that sale of products similar to those described below is criminal, as they are unlicensed medicines.

Radithor, a well known patent medicine/snake oil, is possibly the best known example of radioactive quackery. It consisted of triple distilled water containing at a minimum 1 microcurie each of the radium 226 and 228 isotopes.[23]

Radithor was manufactured from 1918 - 1928 by the Bailey Radium Laboratories, Inc., of East Orange, New Jersey. The head of the laboratories was listed as Dr. William J. A. Bailey, not a medical doctor.[24] It was advertised as "A Cure for the Living Dead"[25] as well as "Perpetual Sunshine".

These radium elixirs were marketed similar to the way opiates were peddled to the masses with laudanum an age earlier, and electrical cure-alls during the same time period such as the Prostate Warmer.[26]

The eventual death of the socialite Eben Byers from Radithor consumption and the associated radiation poisoning led to the strengthening of the Food and Drug Administration's powers and the demise of most radiation quack cures.

Associated links

- Scientific American; August 1993; The Great Radium Scandal; by Roger Macklis

- Theodore Gray's Periodic Table of Elements

Investigation

For an overview please see [1].

Nature of the radioactive source

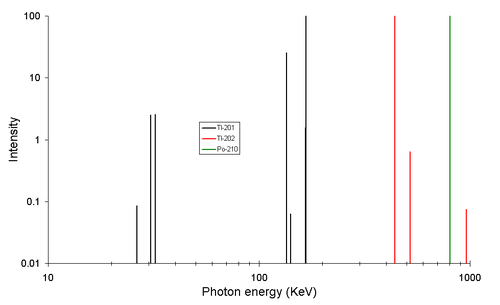

By means of radiometric methods such as Gamma spectroscopy (or a method using a chemical separation followed by an activity measurement with a non-energy-dispersive counter), it is possible to measure the concentrations of radioisotopes and to distinguish one from another. Below is a graph drawn from databooks of how the gamma spectra of three different isotopes which relate to this case using an energy-dispersive counter such as a germanium semiconductor detector or a sodium iodide crystal (doped with thallium) scintillation counter. In this chart the line width of the spectral lines is about 1 keV and no noise is present, in real life background noise would be present and depending on the detector the line width would be larger so making it harder to make an identification and measurement of the isotope. In biological/medical work it is common to use the natural 40K present in all tissues/body fluids as a check of the equipment and as an internal standard.

See also

References

- ^ "Welcome". World Information Service on Energy.. http://www10.antenna.nl/wise/index.html. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ^ "Germany: Plutonium soup as a murder weapon?". World Information Service on Energy. October 5, 2001. http://www10.antenna.nl/wise/index.html?http://www10.antenna.nl/wise/555/5321.html. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ^ "English Edition". German News. 24 February 2005. http://www.germnews.de/archive/dn/2005/02/24.html#16. Retrieved 2006-12-05.[dead link]

- ^ "Clean-up of a GIGA-BQ-PU contamination of two apartments" (pdf). Hagen Hoefer. http://ean.cepn.asso.fr/pdf/program7/Session%20C/C2_HOEFE.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ^ Ray, Ian. "Nuclear Forensic Science and Illicit Trafficking" (pdf). Karlsruhe (Germany): Institute for Transuranium Elements. http://www.jrc.cec.eu.int/more_information/infodays/200210_speech/ray.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-05.

- ^ Maria Wallenius, Klaus Lützenkirchen, Klaus Mayer, Ian Ray, Laura Aldave de las Heras, Maria Betti, Omer Cromboom, Marc Hild, Brian Lynch, Adrian Nicholl, et al., Journal of Alloys and Compounds, In press doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2006.10.161

- ^ "London doctor: Radioactive poison may be in ex-Russian spy". USA Today. 21 November 2006. http://www.usatoday.com/news/world/2006-11-20-spy_x.htm?csp=34. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- ^ "Doctors in dark on poisoned ex-spy". CNN. 21 November 2006. http://www.cnn.com/2006/WORLD/europe/11/21/uk.spypoisoned/index.html. Retrieved 2006-11-22.

- ^ (Spanish)"Murió Alexander Litvinenko, el ex espía ruso que fue envenenado en Londres". El Tiempo. 24 November 2006. http://www.eltiempo.com/internacional/europa/noticias/ARTICULO-WEB-NOTA_INTERIOR-3337667.html. Retrieved 2006-11-24.[dead link]

- ^ "Ex-spy's condition deteriorates". BBC. 24 November 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6176004.stm. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- ^ "Ex-Russian spy dies in hospital". BBC. 24 November 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/6178890.stm. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- ^ Cobain, Ian (24 November 2006). "Poisoned former KGB man dies in hospital". London: The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/russia/article/0,,1955864,00.html. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- ^ Hall, Ben (November 28, 2006). "Polonium 210 found at Berezovsky's office". MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15923659/. Retrieved 2006-12-01.[dead link]

- ^ "Radiation tests after spy death". BBC. 24 November 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/6180682.stm. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- ^ "Health Protection Agency press release". HPA. 24 November 2006. http://www.hpa.org.uk/hpa/news/articles/press_releases/2006/241106_litvinenko.htm. Retrieved 2006-11-24.

- ^ "Nuclide Safety Data Sheet Polonium – 210" (pdf). North Carolina Chapter of the Health Physics Society. http://hpschapters.org/northcarolina/NSDS/210PoPDF.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "Energy Citations Database". Office of Scientific and Technical Information. http://www.osti.gov/energycitations/product.biblio.jsp?osti_id=7162390. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "Dissidents say Stasi gave them cancer". BBC. 25 May 1999. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/352461.stm. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ Stride, Jonathan T. (30 December 1997). "Castro said to be using cancer instigating weapons for warfare". Florida International University. http://www.fiu.edu/~fcf/cancercastro123097.html. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ Montaner, Carlos Alberto (28 December 1997). "The Bulgarian Treatment". Firmas Press. http://www.firmaspress.com/726.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "The Radiological Accident in Cochabamba" (pdf). International Atomic Energy Agency. July 2004. ISBN 92–0–107604–5. http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/Pub1199_web.pdf. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ a b IAEA Illicit Trafficking Database (ITDB) p. 3.

- ^ "Radithor (ca. 1918).". Oak Ridge Associated Universities. 15 September 2004. http://www.orau.org/ptp/collection/quackcures/radith.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "U/A". Literary Digest. 16 April 1932.

- ^ "Radium Cures". Museum of Questionable Medical Devices (Science Museum of Minnesota). 4 February 2000. Archived from the original on 2006-11-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20061110040815/http://www.mtn.org/~quack/devices/radium.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- ^ "Prostate Cures". Museum of Questionable Medical Devices (Science Museum of Minnesota). 18 April 1999. Archived from the original on 2006-12-06. http://web.archive.org/web/20061206005255/http://www.mtn.org/quack/devices/prostate.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

Categories:- Crimes

- Nuclear terrorism

- Nuclear technology-related lists

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.