- John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster

-

This article is about the historical figure John of Gaunt. For places and organisations named after him, see John O'Gaunt.

John of Gaunt

Duke of Lancaster; Duke of Aquitaine Successor Henry Bolingbroke Spouse Blanche of Lancaster

m. 1359; dec. 1369

Infanta Constance of Castile

m. 1371; dec. 1394

Katherine Swynford

m. 1396; wid. 1399Issue Philippa, Queen of Portugal

Elizabeth, Duchess of Exeter

Henry IV of England

Catherine, Queen of Castile

John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset

Cardinal Henry Beaufort

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter

Joan Beaufort, Countess of WestmorlandHouse House of Plantagenet (by birth)

House of Lancaster (founder)Father Edward III of Windsor, King of England Mother Philippa of Hainault Born 6 March 1340

Ghent, BelgiumDied 3 February 1399 (aged 58)

Leicester Castle, LeicestershireBurial St Paul's Cathedral, City of London John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (second creation), KG (6 March 1340 – 3 February 1399) was a member of the House of Plantagenet, the third surviving son of King Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. He was called "John of Gaunt" because he was born in Ghent, rendered in English as Gaunt.

As a younger brother of Edward, Prince of Wales (The Black Prince), John exercised great influence over the English throne during the minority of his nephew, Richard II, and during the ensuing periods of political strife, but was not thought to have been among the opponents of the king.

John of Gaunt's legitimate male heirs, the Lancasters, included Kings Henry IV, Henry V, and Henry VI. His other legitimate descendants included his daughters Queen Philippa of Portugal, wife of John I of Portugal and mother of King Edward of Portugal, and Elizabeth, Duchess of Exeter, mother of John Holland, 2nd Duke of Exeter, through his first wife, Blanche; and by his second wife, Constance, John was father of Queen Catherine of Castile, wife of Henry III of Castile and mother of John II of Castile. John fathered five children outside marriage, one early in life by a lady-in-waiting to his mother, and four surnamed "Beaufort" by Katherine Swynford (after a former French possession of the Duke), Gaunt's long-term mistress and third wife. The Beaufort children, three sons and a daughter, were legitimized by royal and papal decrees after John and Katherine married in 1396; a later proviso that they were specifically barred from inheriting the throne ('excepta regali dignitate') was inserted with dubious authority by half-brother Henry IV. Descendants of this marriage included Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester and eventually Cardinal; Joan Beaufort, Countess of Westmorland, grandmother of Kings Edward IV and Richard III; John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, the great-grandfather of King Henry VII; and Joan Beaufort, Queen of Scots, from whom are descended, beginning in 1437, all subsequent sovereigns of Scotland, and successively, from 1603 on, the sovereigns England, of Great Britain and Ireland, and of the United Kingdom to the present day. The three preceding houses of English sovereigns from 1399 - the Houses of Lancaster, York and Tudor - were descended from John through, respectively, Henry Bolingbroke, Joan Beaufort and John Beaufort.

When John died in 1399, his estates were declared forfeit as King Richard II had exiled John's son and heir, Henry Bolingbroke, in 1398, for 10 years for killing another nobleman. Bolingbroke returned from exile to reclaim his inheritance and deposed Richard. Bolingbroke then reigned as King Henry IV of England (1399–1413), the first of the descendants of John of Gaunt to hold the throne of England.

John of Gaunt was buried beside his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster, in the choir of St Paul's Cathedral. Their magnificent tomb had been designed and executed between 1374 and 1380 by Henry Yevele with the assistance of Thomas Wrek, at a total cost of £592. The two alabaster effigies were notable for having their right hands joined. An adjacent chantry chapel was added between 1399 and 1403.[1]

Contents

Duke of Lancaster

Kenilworth Castle, a massive fortress extensively modernized and given a new Great Hall by John of Gaunt after 1350.

Kenilworth Castle, a massive fortress extensively modernized and given a new Great Hall by John of Gaunt after 1350.

John of Gaunt's first wife, Blanche, was also his third cousin, both being great great grandchildren of King Henry III. They married in 1359 at Reading Abbey as King Edward III arranged matches for his sons with wealthy heiresses. Upon the death of his father-in-law in 1361, John received half of Henry's lands, the title Earl of Lancaster, and the distinction as the greatest landowner in the north of England, inheriting the Palatinate of Lancaster. He also became the 14th Baron of Halton and 11th Lord of Bowland. John inherited the rest when Blanche's sister, Maud, Countess of Leicester (married to William V, Count of Hainaut), died on 10 April 1362. John received the title "Duke of Lancaster" from his father on 13 November 1362. John was by then well established, owning at least thirty castles and estates across England and France. His household was comparable in scale and organization to that of a monarch. He owned land in almost every county in England, producing a net income of between £8,000 and £10,000 a year (several millions in today's terms).[2]

After the death of his older brother Edward of Woodstock (also known as The Black Prince), John of Gaunt contrived to protect the religious reformer John Wyclif, possibly to counteract the growing secular power of the Roman Catholic Church. However, John's ascendancy to political power coincided with widespread resentment of his influence. At a time when English forces encountered setbacks in the Hundred Years' War against France, and Edward III's rule was becoming unpopular due to high taxation and his affair with Alice Perrers, political opinion closely associated the Duke of Lancaster with the failing government of the 1370s. Furthermore, while King Edward and the Prince of Wales were popular heroes due to their successes on the battlefield, John of Gaunt had not won equivalent military renown that could have bolstered his reputation. Although he fought in the Battle of Nájera, for example, his later military projects were unsuccessful.

When King Edward III died in 1377 and John's ten-year-old nephew succeeded as Richard II of England, John's influence strengthened. However, mistrust remained, and some suspected him of wanting to seize the throne himself. John took pains to ensure that he never became associated with the opposition to Richard's kingship. As virtual ruler during Richard's minority, he made unwise decisions on taxation that led to the Peasants' Revolt in 1381, when the rebels destroyed his Savoy Palace in London. Unlike some of Richard's other unpopular advisors, John was away from London at the time of the uprising and thus avoided the wrath of the rebels.

In 1386, John left England to claim the throne of Castile. However, crisis ensued almost immediately, and in 1387, King Richard's misrule brought England to the brink of civil war. Only John, on his return to England in 1389, was able to persuade the Lords Appellant and King Richard to compromise, ushering in a period of relative stability. During the 1390s, John's reputation of devotion to the well-being of the kingdom was largely restored. John died of natural causes on 3 February 1399 at Leicester Castle, with his third wife Katherine by his side.

Military commander in France

Because of his rank John of Gaunt was one of England's principal military commanders in the 1370s and 1380s, though his enterprises were never rewarded with the kind of dazzling success that had made his elder brother the Black Prince such a charismatic war leader.

On the resumption of war with France in 1369, John was sent to Calais with the Earl of Hereford and a small English army with which he raided into northern France. On 23 August he was confronted by a much larger French army under Philip, Duke of Burgundy. Exercising his first command, Gaunt dared not attack such a superior force and the two armies faced each other across a marsh for several weeks until the English were reinforced by the Earl of Warwick, at which the French withdrew without offering battle. Gaunt and Warwick then decided to strike Harfleur, the base of the French fleet on the Seine. Further reinforced by German mercenaries, they marched on Harfleur but were delayed by French guerilla operations while the town prepared for a siege. John invested the town for four days in October, but he was losing so many men to dysentry and bubonic plague that he decided to abandon the siege and return to Calais. During this retreat the army had to fight its way across the Somme at the ford of Blanchetaque against a French army led by Hugh de Châtillon, who was captured and sold to Edward III. The survivors of the sickly army returned to Calais, where the Earl of Warwick died of plague, by the middle of November. Though it seemed an inglorious conclusion to the campaign, Gaunt had forced the French king, Charles V, to abandon his plans to invade England that autumn.[3]

In the summer of 1370 John was sent with a small army to Aquitaine to reinforce his ailing elder brother, the Black Prince and his younger brother Edmund of Langley, Earl of Cambridge. With them he participated in the sack of Limoges, after which the Black Prince surrendered his lordship of Aquitaine and sailed for England, leaving John in charge. Though he attempted to defend the duchy against French encroachment for nearly a year, lack of resources and money meant he could do little but husband what little territory the English still controlled, and he resigned the command in September 1371 and returned to England.[4] Just before leaving Aquitaine, on 21 September 1371 he married Infanta Constance of Castile at Roquefort, near Bordeaux, Guienne. The following year he took part with his father, Edward III, in an abortive attempt to invade France with a large army, which was frustrated by three months of unfavourable winds.

Probably John's most notable feat of arms occurred in August–December 1373, when he attempted to relieve Aquitaine by the landward route, leading an army of some 9,000 mounted men from Calais on a great chevauchée from north-eastern to south-western France on a 900 kilometer raid. This four-month ride through enemy territory, evading French armies on the way, was a bold stroke which impressed contemporaries but achieved virtually nothing. Beset on all sides by French ambushes and plagued by disease and starvation, John of Gaunt and his raiders battled their way through Champagne, east of Paris, into Burgundy, across the Massif Central, and finally down into Dordogne. Unable to attack any strongly fortified forts and cities, the raiders plundered the countryside, raiding towns and villages, weakening the French infrastructure, but the military value of the damage was only temporary. Marching in winter across the Limousin plateau, with stragglers being picked off by the French, huge numbers of the army, and even larger numbers of horses, died of cold, disease or starvation. The army reached English-occupied Bordeaux on 24 December 1373, severely weakened in numbers and capacity having lost at least one-third of their force in action and another third to disease, and many more then succumbed to the bubonic plague that was raging in the city. Sick, demoralized and mutinous, the army was in no shape to defend Aquitaine, and soldiers began to desert. Gaunt had no funds with which to pay them, and despite his entreaties none were sent from England, so in April 1374 he abandoned the enterprise and sailed for home.[5]

John's final campaign in France was in 1378; he planned a 'great expedition' of mounted men in a large armada of ships to land at Brest and take control of Brittany. Not enough ships could be found to transport the horses, and the expedition was tasked with the more limited objective of capturing St. Malo. The English destroyed the shipping in St. Malo harbour and began to assault the town by land on 14 August, but John was soon hampered by the size of his army, which was unable to forage because French armies under Olivier de Clisson and Bertrand du Guesclin occupied the surrounding countryside, harrying the edges of his force. In September the siege was simply abandoned and the army returned ingloriously to England. John of Gaunt received most of the blame for the debâcle.[6]

Partly as a result of these failures, and those of other English commanders at this period, John was one of the first important figures in England to conclude that the war with France was unwinnable because of France's greater resources of wealth and manpower. He began to advocate peace negotiations - indeed as early as 1373, during his great raid through France, he made contact with Guillaume Roger, brother and political adviser of Pope Gregory XI, to let the Pope know he would be interested in a diplomatic conference under papal auspices. This approach led indirectly to the Anglo-French Congress of Bruges in 1374-77, which resulted in a short-lived truce between the two sides.[7] John was himself a delegate to the various conferences that eventually resulted in the Truce of Leulinghem in 1389. The fact that he became identified with the attempts to make peace added to his unpopularity at a period when the majority of Englishmen believed victory would be in their grasp if the French could be roundly defeated as they had been in the 1350s. Another motive was John's conviction that it was only by making peace with France that it would be possible to release sufficient manpower to enforce his claim to the throne of Castile.

Head of Government

On his return from France in 1374, John took a more decisive and persistent role in the direction of English foreign policy, and from then until 1377, owing to the fact that his father and elder brother were both ill and unable to exercise their authority, he was effectively the head of the English government. It was rumoured (and believed by many people in England and France) that he intended to seize the throne for himself and supplant the rightful heir, his nephew Richard, the Black Prince's son, but there seems to have been no truth in this and on the death of Edward III and the accession of the child Richard II Gaunt sought no position of regency for himself and withdrew to his estates.[8]

'King of Castile'

On his marriage to Infanta Constance of Castile in 1371, John assumed (officially from 29 January 1372) the title of King of Castile and Leon in right of his wife, and insisted his fellow English nobles henceforth address him as 'my lord of Spain.' He impaled his arms with those of the Spanish kingdom. From 1372 John gathered around himself a small court of refugee Castilian knights and ladies and set up a Castilian chancery which prepared documents in his name according to the style of Pedro I of Castile, dated by the Castilian era and signed by himself with the Spanish formula 'Yo El Rey' (I, the King).[9] He hatched several schemes to make good his claim with an army, but for many years these were still-born due to lack of finance or the conflicting claims of war in France or with Scotland. It was only in 1386, after Portugal under its new king John of Avis had entered into full alliance with England, that he was actually able to land with an army in Spain and mount an ultimately unsuccessful campaign for the throne of Castile. John sailed from England on 9 July 1386 with a huge Anglo-Portuguese fleet, carrying an army of about 5,000 men plus an extensive 'royal' household and his wife and daughters. Pausing on the journey to use his army to drive off the French forces who were then besieging Brest, he landed at Corunna in northern Spain on 29 July.

The Castilian king, John of Trastámara, had expected Gaunt would land in Portugal and had concentrated his forces on the Portuguese border; he was wrong-footed by Gaunt's decision to invade Galicia, the most distant and disaffected of Castile's provinces. From August to October, John of Gaunt set up a rudimentary court and chancery at Orense and received the submission of most of the towns of Galicia, though they made their homage to him conditional on his being recognized as king by the rest of Castile. While John of Gaunt had gambled on an early decisive battle, the Castilians were in no hurry to join battle, and he began to experience difficulties keeping his army together and paying it. In November he met Joao I of Portugal at Ponte do Mouro on the south side of the Minho River and concluded an agreement with him to make a joint Anglo-Portuguese invasion of central Castile early in 1387. The treaty was sealed by the marriage of John's eldest daughter Philippa to the Portuguese King. A large part of John's army had succumbed to sickness, however, and when the invasion was mounted they were far outnumbered by their Portuguese allies. The campaign (April–June 1387) was an ignominious failure. The Castilians refused to offer battle and the Anglo-Portuguese troops, apart from time-wasting sieges of fortified towns, were reduced to foraging for food in the arid Spanish landscape. They were harried mainly by French mercenaries of the Castilian King. Many hundreds of English, including close friends and retainers of John of Gaunt, died of disease or exhaustion. Many deserted or abandoned the army to ride north under French safe-conducts. Shortly after the army returned to Portugal, John of Gaunt concluded a secret treaty with John of Trastámara under which he and his wife renounced all claim to the Castilian throne in return for a large annual payment and the marriage of his daughter Catherine to John of Trastámara's son Henry.

Marriages and descendants

- John's first child was an illegitimate daughter, Blanche (1359-1388/89). Blanche was the daughter of John's mistress Marie de St. Hilaire of Hainaut (1340-after 1399), who was a lady in waiting to his mother, Queen Philippa. The affair apparently took place before John's first marriage, which was to his cousin Blanche of Lancaster. John's daughter, Blanche, married Sir Thomas Morieux in 1381. Morieux held several important posts, including Constable of the Tower the year he was married, and Master of Horse to King Richard II two years later. He died in 1387 after six years of marriage.

- On 19 May 1359 at Reading Abbey, John married his third cousin, Blanche of Lancaster, daughter of Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster. The wealth she brought to the marriage was the foundation of John's fortune. Blanche died of bubonic plague on 12 September 1369 at Bolingbroke Castle, while her husband was away at sea. Their son Henry Bolingbroke became Henry IV of England, after the duchy of Lancaster was taken by Richard II upon John's death while Henry was in exile. Their daughter Philippa became Queen of Portugal by marrying King John I of Portugal in 1387. All subsequent kings of Portugal were thus descended from John of Gaunt.

- In 1371, John married Infanta Constance of Castile, daughter of King Peter of Castile, thus giving him a claim to the Crown of Castile, which he would pursue. Though John was never able to make good his claim, his daughter by Constance, Katherine of Lancaster, became Queen of Castile by marrying Henry III of Castile.

- During his marriage to Constance, John of Gaunt had fathered four children by a mistress, the widow Katherine Swynford (whose sister Philippa de Roet was married to Chaucer). Prior to her widowhood, Katherine had borne at least two, possibly three, children to Lancastrian knight Sir Hugh Swynford. The known names of these children are Blanche and Thomas. (There may have been a second Swynford daughter.) John of Gaunt was Blanche Swynford's godfather.[10]

Constance died in 1394. John married Katherine in 1396, and their children, the Beauforts, were legitimised by King Richard II and the Church, but barred from inheriting the throne. From the eldest son, John, descended a granddaughter, Margaret Beaufort, whose son, later King Henry VII of England, would nevertheless claim the throne.

All monarchs of England and later of Great Britain, the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth Realms from Henry IV onwards are descended from John of Gaunt.

Children

- By Blanche of Lancaster:

- Philippa (1360–1415), married King John I of Portugal (1357–1433)

- John (1362–1365), he was the first born son of John and Blanche of Lancaster and lived possibly at least until after the birth of his brother Edward of Lancaster in 1365 and died before his second brother another short lived boy called John in 1366.[11] He was buried Church of St Mary de Castro, Leicester.

- Elizabeth (1364–1426), married (1) in 1380 John Hastings, 3rd Earl of Pembroke (1372–1389), annulled 1383; married (2) in 1386 John Holland, 1st Duke of Exeter (1350–1400); (3) Sir John Cornwall, 1st Baron Fanhope and Milbroke (d. 1443)

- Edward (1365) he died later the same year of his birth; He was buried Church of St Mary de Castro, Leicester

- John (1366–1367) he most likely died after the birth of his younger brother Henry the future Henry IV of England; Buried Church of St Mary de Castro, Leicester

- Henry IV of England (1367–1413), married (1) Mary de Bohun (1369–1394); (2) Joanna of Navarre (1368–1437)

- Isabel (1368–1368)[12][13]

- By Constance of Castile:

- Catherine (1372–1418), married King Henry III of Castile (1379–1406)

- John (1374–1375)[13][14]

- By Katherine Swynford (née de Roet/Roelt), mistress and later wife (children legitimised 1397):

- John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset (1373–1410) – married Margaret Holland.

- Henry Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester and Cardinal (1375–1447)

- Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter (1377–1427), married Margaret Neville, daughter of Sir Thomas de Neville and Joan Furnivall.

- Joan Beaufort (1379–1440) – married first Robert Ferrers, 5th Baron Boteler of Wem and second Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmoreland.

- By Marie de St. Hilaire of Hainaut, mistress:

- Blanche(1359–1388/89), married Sir Thomas Morieux (1355–1387) in 1381, without issue

Relationship to Chaucer

John of Gaunt was a patron of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer who recorded much of the mores of England at the time of John in The Canterbury Tales. Near the end of John's life, they were brothers-in-law. Chaucer was married to Philippa de Roet; John's third wife, Katherine, was Philippa's sister. John's children by Katherine were Chaucer's nieces and nephews.

Chaucer's Book of the Duchess, also known as The Deth of Blaunche, was written in commemoration of Blanche of Lancaster, John's first wife. The poem refers to John and Blanche in allegory as the "Black Knight" and the "Lady White." "Blanche" means "white." At the end of the poem reference is made to John's marriage to Blanche by playing on the sound of their titles of Lancaster and Richmond in the form of "long castel" (line 1318) and "riche hil" (line 1319).

Some have suggested that the "long castel" line could also refer to Constanza of Castile, John's second wife, and the heraldic arms of Castile, which display a castle, part of the tradition of heraldic canting arms.

Titles, styles, arms and honours

Arms

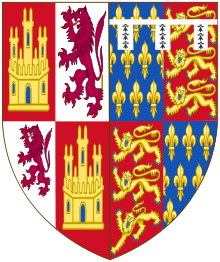

As a son of the sovereign, John bore the royal arms of the kingdom (Quarterly, France Ancient and England), differenced by a label argent of three points ermine.[15]

As claimant to the throne of Castile and Leon from 1372, he impaled the arms of that kingdom (Gules, a castle or, quartering Argent, a lion rampant purpure) with his own. The arms of Castile and Leon appeared on the dexter side of the shield (the left hand side as viewed), and the differenced English royal arms on the sinister; but in 1388, when he surrendered his claim, he reversed this marshalling, placing his own arms on the dexter, and those of Castile and Leon on the sinister.[16] He thus continued to signal his alliance with the Castilian royal house, while abandoning any claim to the throne. There is, however, evidence that he may occasionally have used this second marshalling at earlier dates.[17]

In addition to his royal arms, Gaunt also bore an alternative coat of Sable, three ostrich feathers ermine. This was the counterpart to his brother, the Black Prince's, 'shield for peace' (on which the ostrich feathers were white), and may have been used in jousting. The ostrich feather arms appeared in stained glass above Gaunt's chantry chapel in St Paul's Cathedral.[18]

Popular culture

Lancaster city centre has a public house called The John O'Gaunt. An administrative ward on the city council also bears the name.

Hungerford in Berkshire also has ancient links to the Duchy, the manor becoming part of John of Gaunt's estate in 1362 before James I passed ownership to two local men in 1612 (which subsequently became Hungerford Town & Manor). The links are visible today in the Town and Manor-owned John O'Gaunt pub, the John O'Gaunt state secondary school, as well as various street names. It is also customary for the Loyal Toast to be given by residents as "The Queen, the Duke of Lancaster". There is also a secondary school in Trowbridge, Wiltshire bearing the same name, which is built upon land that he once owned.

John held large tracts of land in Lincolnshire and the City of Lincoln. At the appropriately named site of Gaunt Street, he maintained a palace, remains of which were found in the late 1960s. A Finial window, complete, was found between two walls in the then 'West's Garage'. This was moved and now adorns the entrance through the East bail of Lincoln castle.

Opposite the Palace site, stands St.Mary's Guildhall, locally known as John O'Gaunt's stables. This large medieval building, once formed the entrance to the Football ground of Lincoln City F.C., until they moved to their present ground. It was known as The John O'Gaunt ground.

The remnants of the castle at Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, once owned by John, sit on John o' Gaunt's Street.

The John of Gaunt Stakes is a British race for Thoroughbred horses run annually in June.

In William Shakespeare's play Richard II, the famous England speech is spoken by the character of John of Gaunt as he lies on his deathbed.

- This royal throne of kings, this scepter'd isle,

- This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

- This other Eden, demi-paradise,

- This fortress built by Nature for herself

- Against infection and the hand of war,

- This happy breed of men, this little world,

- This precious stone set in the silver sea,

- Which serves it in the office of a wall,

- Or as a moat defensive to a house,

- Against the envy of less happier lands,

- This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England,

- This nurse, this teeming womb of royal kings,

- Fear'd by their breed and famous by their birth

- Renowned for their deeds as far from home,

- For Christian service and true chivalry,

- As is the sepulchre in stubborn Jewry,

- Of the world's ransom, blessed Mary's Son,

- This land of such dear souls, this dear dear land,

- Dear for her reputation through the world,

- Is now leased out, I die pronouncing it,

- Like to a tenement or pelting farm:

- England, bound in with the triumphant sea

- Whose rocky shore beats back the envious siege

- Of watery Neptune, is now bound in with shame,

- With inky blots and rotten parchment bonds:

- That England, that was wont to conquer others,

- Hath made a shameful conquest of itself.

- Ah, would the scandal vanish with my life,

- How happy then were my ensuing death!

- —Act II, scene i, 42–54

The Tragedy of King Richard II at Wikisource

Anya Seton's bestselling 1954 novel Katherine depicts John's long-term affair with and eventual marriage to Katherine Swynford.

The eponymous character of the US comic book series GrimJack is legally named John Gaunt. According to author John Ostrander, he took the name from the historical figure simply because it sounded impressive, without any specific historical reference.

John of Gaunt is a major character in Garry O'Connor's Chaucer’s Triumph: Including the Case of Cecilia Chaumpaigne, the Seduction of Katherine Swynford, the Murder of Her Husband, the Interment of John of Gaunt and Other Offices of the Flesh in the Year 1399.

John O'Gaunt is a piece of music written for Brass Band by Gilbert Vinter in 1965. It documents John O'Gaunts life in a musical tone poem.

The romance novel "Almost Innocent" by Jane Feather tells the story of a possibly fictitious illegitimate daughter of John of Gaunt, and contains much history and vivid description of John and of royal life.

John of Gaunt's armour has been on display in the Tower of London for many years, and is of exceptional size, since the man himself was 6'7" tall. However, in her biography of Katherine Swynford (2007), Alison Weir states that this is legend and that the armor in question is of German origin, not English.

References

- ^ Oliver D. Harris, ‘"Une tresriche sepulture": the tomb and chantry of John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster in Old St Paul’s Cathedral, London', Church Monuments, vol. 25 (2010), pp. 7-35

- ^ Sumption (2009), p. 3.

- ^ Jonathan Sumption, Divided Houses: The Hundred Years War III (London: Faber & Faber, 2009), pp. 38-69.

- ^ Sumption (2009), pp. 69-108.

- ^ Sumption (2009), pp. 187-202.

- ^ Sumption (2009), pp. 325-327.

- ^ Sumption (2009), pp. 212-213.

- ^ Sumption (2009), pp. 213, 283-4.

- ^ Sumption (2009), pp. 122-3.

- ^ Dame Blanche Morieux in John of Gaunt: King of Castile and Leon, Duke of Aquitaine and Lancaster by Sydney Armitage-Smith, pp. 460-461. (1904, 1905). Accessed 11 March 2008.

- ^ Weir, Alison., Katherine Swynford the story of John of Gaunt and his scandalous duchess (London, 2008) pg. 43

- ^ Leese, Thelma Anna, Blood royal: issue of the kings and queens of medieval England, 1066-1399, (Heritage Books Inc., 1996), 219.

- ^ a b G.E. Cokayne; with Vicary Gibbs, H.A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, editors, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed, 13 volumes in 14 (1910-1959 reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, U.K. Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000), volume XII/2, page 908 Hereinafter cited as The Complete Peerage

- ^ Leese, Thelma Anna, Blood royal: issue of the kings and queens of medieval England, 1066-1399, (Heritage Books Inc., 1996), 222.

- ^ Marks of Cadency in the British Royal Family

- ^ Armitage-Smith, John of Gaunt, pp. 456–57.

- ^ P.A. Fox, ‘Fourteenth-century ordinaries of Arms. Part 2: William Jenyns’ Ordinary’, Coat of Arms, 3rd ser. vol. 5 (2009), pp. 55–64 (pp. 59, 61, pl. 2).

- ^ Harris, '"Tresriche sepulture"', pp. 22-3

Further reading

- Armitage-Smith, Sydney (1904) John of Gaunt, King of Castile and Leon, Duke of Lancaster, &c. London: Constable

- Cantor, Norman F. (2004) The Last Knight: the Twilight of the Middle Ages and the Birth of the Modern Era New York: Free Press, 2004

- Goodman, Anthony (1992) John of Gaunt: the Exercise of Princely Power in Fourteenth-Century Europe. New York: St. Martin's Press

- Green, V.H.H. (1955) The Later Plantagenets: A Survey of English History 1307-1485 Edward Arnold

- Harris, Oliver D., ‘"Une tresriche sepulture": the tomb and chantry of John of Gaunt and Blanche of Lancaster in Old St Paul’s Cathedral, London', Church Monuments, vol. 25 (2010), pp. 7-35

- Nicolle, David (2011) The Great Chevauchée; John of Gaunt's Raid on France 1373. Osprey Raid Series #20. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978 1 84908 247 1

- Walker, Simon (1990) The Lancastrian Affinity, 1361–1399 Oxford: Clarendon Press

External links

- Information about John of Gaunt by Sandra Grünewald

- Sir Jean Froissart: John of Gaunt in Portugal, 1385

- The Katherine Swynford Society website

Ancestry

Ancestors of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster 16. Henry III of England 8. Edward I of England 17. Eleanor of Provence 4. Edward II of England 18. Ferdinand III of Castile 9. Eleanor, Countess of Ponthieu 19. Joan, Countess of Ponthieu 2. Edward III of England 20. Philip III of France 10. Philip IV of France 21. Isabella of Aragon 5. Isabella of France 22. Henry I of Navarre 11. Joan I of Navarre 23. Blanche of Artois 1. John of Gaunt 24. John I, Count of Hainaut 12. John II, Count of Holland 25. Adelaide of Holland 6. William I, Count of Hainaut 26. Henry V, Count of Luxembourg 13. Philippa of Luxembourg 27. Margaret of Bar 3. Philippa of Hainault 28. Philip III of France 14. Charles, Count of Valois 29. Isabella of Aragon 7. Joan of Valois 30. Charles II of Naples 15. Margaret, Countess of Anjou 31. Mary of Hungary John of GauntBorn: 6 March 1340 Died: 3 February 1399Regnal titles Preceded by

Richard IIDuke of Aquitaine

1390–1399Succeeded by

Henry BolingbrokePeerage of England New creation Duke of Lancaster

1362–1399Succeeded by

Henry BolingbrokePreceded by

Henry of GrosmontEarl of Leicester

Earl of Lancaster

Earl of Derby

1361–1399Political offices Preceded by

Henry of GrosmontLord High Steward

1362–1399Succeeded by

Henry BolingbrokeHM The Queen

Henry of Grosmont (1351-1361) · John of Gaunt (1362-1399) · Henry IV (1399) · Henry V (1399-1413 – merged in crown)Categories:- 1340 births

- 1399 deaths

- People from Ghent

- House of Lancaster

- Princes of England

- Pretenders to the throne of the kingdom of Castile

- Dukes of Lancaster

- Earls of Richmond

- Lord High Stewards

- Knights of the Garter

- English people of French descent

- English people of Greek descent

- English people of Serbian descent

- English people of Scottish descent

- English people of Spanish descent

- High Sheriffs of Lancashire

- Burials at St Paul's Cathedral

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.