- Hassan-i Sabbah

-

Part of a series on Shī‘ah Islam Ismāʿīlism

Concepts The Qur'ān · The Ginans

Reincarnation · Panentheism

Imām · Pir · Dā‘ī l-Muṭlaq

‘Aql · Numerology · Taqiyya

Żāhir · BāṭinSeven Pillars Guardianship · Prayer · Charity

Fasting · Pilgrimage · Struggle

Purity · Profession of FaithHistory Shoaib · Nabi Shu'ayb

Seveners · Qarmatians

Fatimids · Baghdad Manifesto

Hafizi · Taiyabi

Hassan-i Sabbah · Alamut

Sinan · Assassins

Pir Sadardin · Satpanth

Aga Khan · Jama'at Khana

Huraat-ul-Malika · BöszörményEarly Imams Ali · Ḥassan · Ḥusain

as-Sajjad · al-Baqir · aṣ-Ṣādiq

Ismā‘īl · Muḥammad

Abdullah /Wafi

Ahmed / at-Taqī

Husain/ az-Zakī/Rabi · al-Mahdī

al-Qā'im · al-Manṣūr

al-Mu‘izz · al-‘Azīz · al-Ḥākim

az-Zāhir · al-Mustansir · Nizār

al-Musta′lī · al-Amīr · al-QāṣimGroups and Present leaders Nizārī · Aga Khan IV

Dawūdī · Burhanuddin

Sulaimanī · Al-Fakhri Abdullah

Alavī · Ṭayyib Ziyā'u d-DīnMain article: NizariHassan-i Sabbāh (Persian: حسن صباح Hasan-e Sabbāh, 1050s–1124) was a Persian Nizārī Shi'a Ismā'īlī Muslim missionary who converted a community in the late 11th century in the heart of the Alborz Mountains of northern Iran. The place was called Alamut and was attributed to an ancient king of Daylam. He founded a group whose members are sometimes referred to as the Hashshashin or "Soldiers" to protect from attackers outside of Iran.

Contents

Sources

Hassan is thought to have written an autobiography, which does not survive but seems to underlie the first part of an anonymous Isma'ili biography entitled Sargudhasht-i Sayyidnā. The latter is known only from quotations made by later Persian authors.[1] Hassan also wrote a Persian treatise on the doctrine of ta'līm, i.e. the teachings of the imam. The text is no longer extant, but fragments are cited or paraphrased by al-Shahrastānī and several Persian historians. He is the original Grand Master creating many of its main principles and foundations.

Early life and conversion

Qom and Rayy

The possibly autobiographical information found in Sargudhasht-i Sayyidnā is the main source for Hassan's background and early life. According to this, Hassan-i Sabbāh was born in the city of Qom (modern Iran) in Persia in the 1050s to a family of Twelver Shī‘ah.[1] His father was an Arab claiming Yemeni descent, who left the Sawād of Kufa hej (modern Iraq) to settle in the (predominantly Shi'a) town of Qom.[2]

Early in his life, his family moved to Rayy.[1] Rayy (Modern Tehran) was a city that had seen a lot of radical thought since the 9th century and it had seen Hamdan Qarmaṭ as one of its voices. It had also seen a lot of missionary work by various sects, each as impassioned as the next.[citation needed]

It was in this centre of religious matrices that Hassan developed a keen interest in metaphysical matters and adhered to the Twelver code of instruction. From 7 to 17,[3] he studied at home, and mastered perfectly palmistry, languages, philosophy, astronomy and mathematics (especially geometry).[4]

Rayy was also home to the activities of Ismā‘īlī missionaries in the Jibal. At the time, Isma'ilism was a growing movement in Persia and other lands east of Egypt.[5] The Persian Isma'ilis supported the da'wa ("mission") directed by the Fatimid caliphate of Cairo and recognised the authority of the Imam-Caliph al-Mustanṣir (d. 1094), though since some time, Isfahan rather than Cairo may have functioned as their principal headquarters.[5] The Ismā'īlī mission worked on three layers: the lowest was the foot soldier or fidā'ī, followed by the rafīk or "comrade", and finally the Dā‘ī or "missionary". It has been suggested that its popularity in Persia owed something to dissatisfaction with their Seljuk rulers, who had recently removed local rulers.[1]

In Rayy, young Hassan came in touch with Amira Darrab, a comrade, who introduced him to Ismā'īlī doctrine. Hassan was initially unimpressed. As he met Darrab, participating in many passionate debates that discussed the merits of Ismā‘īl over Mūsā, Hassan's respect grew. Impressed with the conviction of Darrab, Hassan decided to delve deeper into Ismā'īlī doctrines and beliefs. Hassan began to see merit in switching to Ismā‘īlī.

Conversion to Ismailism and training in Cairo

At the age of 17, Hassan converted and swore allegiance to the Fatimid Caliph in Cairo. Hassan's studies did not end with his crossing over. He further studied under two other dā‘iyyayn, and as he proceeded on his path, he was looked upon with eyes of respect.

Hassan's austere and devoted commitment to the da'wa brought him in audience with the chief missionary of the region: ‘Abdu l-Malik ibn Attash. Ibn Attash, suitably impressed with the young seventeen year old Hassan, made him Deputy Missionary and advised him to go to Cairo to further his studies.

However, Hassan did not go to Cairo. Some historians have postulated that Hassan, following his conversion, was playing host to some members of the Fatimid caliphate, and this was leaked to the anti-Fatimid and anti-Shī‘a Nizam al-Mulk. This prompted his abandoning Rayy and heading to Cairo in 1076.

Hassan took about 2 years to reach Cairo. Along the way he toured many other regions that did not fall in the general direction of Egypt. Isfahan was the first city that he visited. He was hosted by one of the Missionaries of his youth, a man who had taught the youthful Hassan in Rayy. His name was Resi Abufasl and he further instructed Hassan.

From here he went to Azerbaijan, hundreds of miles to the north, and from there to Turkey. Here he attracted the ire of priests following a heated discussion, and Hassan was thrown out of the town he was in.

He then turned south and traveled through Iraq, reached Damascus in Syria. He left for Egypt from Palestine. Records exist, some in the fragmentary remains of his autobiography, and from another biography written by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in 1310, to date his arrival in Egypt at 30 August 1078.

It is unclear how long Hassan stayed in Egypt: about 3 years is the usually accepted amount of time. He continued his studies here, and became a full missionary.

Return to Persia

Whilst he was in Cairo, studying and preaching, he upset the highly excitable Chief of the Army, Badr al-Jamalī. It is also said by later sources that the Ismaili Imam-Caliph al-Mustanṣir informed Hassan that his elder son Nizar would be the next Imam. Hassan was briefly imprisoned by Badr al-Jamali. The collapse of a minaret of the jail was taken to be an omen in the favor of Hassan and he was promptly released and deported. The ship that he was traveling on was wrecked. He was rescued and taken to Syria. Traveling via Aleppo and Baghdad, he terminated his journey at Isfahan in 1081.

Hassan’s life now was totally devoted to the mission. Hassan toured extensively throughout Iran. To the north of Iran, and touching the south shore of the Caspian Sea, are the mountains of Alborz. These mountains were home to a people who had traditionally resisted all attempts at subjugation; this place was also of Shī‘a leaning. Within these mountains, in the region of Daylam, Hassan chose to pursue his missionary activities. Hassan became the Chief Missionary of that area and sent his personally trained missionaries into the rest of the region.

The news of this Ismā'īlī's activities reached Nizam al-Mulk, who dispatched his soldiers with the orders for Hassan's capture. Hassan evaded them, and went deeper into the mountains.

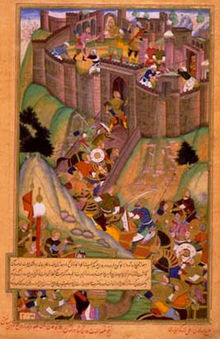

Capture of Alamut

Hashshashin fortress of Alamut

Hashshashin fortress of Alamut

His search for a base from where to guide his mission ended when he found the castle of Alamut in the Rudbar area in 1088. It was a fort that stood guard to a valley that was about fifty kilometers long and five kilometers wide. The fort had been built about the year 865; legend has it that it was built by a king who saw his eagle fly up to and perch upon a rock, of which the king, Wah Sudan ibn Marzuban, understood the importance. Likening the perching of the eagle to a lesson given by it, he called the fort Aluh Amut: the "Eagles Teaching".

Hassan’s takeover of the fort was one of silent surrender in the face of defeated odds. To effect this takeover Hassan employed an ingenious strategy: it took the better part of two years to effect. First Hassan sent his Daʻiyyīn and Rafīks to win the villages in the valley over. Next, key people were converted and in 1090 Hassan took over the fort. It is said that Hassan offered 3000 gold dinars to the fort owner for the amount of land that would fit a buffalo’s hide. The term having been agreed upon, Hassan cut the hide in to strips and link the strips around the perimeter of the fort. The owner was defeated. (This story bears striking resemblance to Virgil's account of Dido's founding of Carthage.) Hassan gave him a draft on the name of a wealthy landlord and told him to take the money from him. Legend further has it that when the landlord saw the draft with Hassan’s signature, he immediately paid the amount to the fort owner, astonishing him.

With Alamut as his, Hassan devoted himself so faithfully to study, that it is said that in all the years that he was there – almost 35, he never left his quarters, except the two times when he went up to the roof. He was studying, translating, praying, fasting, and directing the activities of the Daʻwa: the propagation of the Nizarī doctrine was headquartered at Alamut. He knew the Qur'ān by heart, could quote extensively from the texts of most Muslim sects, and apart from philosophy, he was well versed in mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, medicine, architecture, and the major science fields of his time.[6] Hassan was one who found solace in austerity and frugality. A pious life was one of prayer and devotion. Hassan was a charismatic revolutionary; it was said that by the sheer gravity of his conviction he could pierce the hardest and most orthodox of hearts and win them over to his side.

From this point on his community and its branches spread throughout Iran and Syria and came to be called Hashshashin or Assassins, a mystery cult.

Hassan was extremely strict and disciplined. The event of the Great Resurrection (al-qiyāmat al-kubrā) occurred under the later Ismaili Imam Hasan ala-dhikrihi as-salaam in 1164.

Legacy

Most of his life sketch and early Hashashin is obtained through the historical accounts written in the Islamic world and a few accounts were also written on the orders of Halagu Khan, who before destroying everything, gave order to his Chief Minister to write a complete history of the Assassins (based on the records in the Alamut library) and this is where most of the historical data about the order comes from.[7] They either stem from Sunni polemicists who were motivated to discredit the Nizari Isma'ili on political and religious grounds, or Crusaders returning to Europe. Marco Polo also claimed to have visited Alamut, although the timeframe he gives makes his assertion dubious at best.[7][8][9]

His support and involvement with the series of killings of famous scholars, Imams and other noble personalities has given him title of one of the very first terrorist organization in the world. Some of the famous killings and events in those medieval centuries by Hashashin included the following;[9]

- 1092: The famous Seljuq vizier Nizam al-Mulk is murdered by an Assassin in Baghdad. He becomes their first victim.

- 1094: Al-Mustansir dies, and Hassan does not recognize the new caliph, al-Musta'li. He and his followers transferred their allegiance to his brother Nizar. The followers of Hassan soon even came at odds with the caliph in Baghdad too.

- 1113: Following the death of Aleppo's ruler, Ridwan, the Assassins are driven out of the city by the troops of Ibn al-Khashab.

- 1110's: The Assassins in Syria changes their strategy, and start undercover work and builds cells in all cities around the region.

- 1123: Ibn al-Khashab is killed by an Assassin killer.

- 1124: Hassan dies in Alamut, but the organization lives on stronger than ever. — The leading qadi Abu Saad al-Harawi is killed by an Assassin killer.

It is believed that almost thousands of scholars were killed by Hashashin in that era. After the death of Hassan, some notable events included the following;

- 1126 November 26: Emir Porsuki of Aleppo and Mosul is killed by an Assassin killer.

- 12th century: The Assassins extend their activities into Syria, where they could get much support from the local Shi'i minority as the Seljuq sultanate had captured this territory.

- The Assassins captures a group of castles in the Nusayriyya Mountains (modern Syria). The most important of these castles were the Masyaf, from which the "The Old Man of Mountain", Rashideddin Sinan ruled practically independent from the main leaders of the Assassins.

- 1173: The Assassins of Syria enter negotiations with the king of Jerusalem, with the aim of converting to Christianity. But as the Assassins by now were numerous and often worked as peasants, they paid high taxes to local Christian landlords, that Christian peasants were exempted from. Their conversion was opposed by them, and this year the Assassin negotiators were murdered by Christian knights. After this, there was no more talk of conversion.

- 1175: Rashideddin's men make two attempts on the life of Saladin, the leader of the Ayyubids. The second time, the Assassin came so close that wounds were inflicted upon Saladin.

- 1256: Alamut fortress falls to the Mongols under the leadership of Hülegü. Before this happened, several other fortresses had been captured, and finally Alamut was weak and with little support.

- 1257: The Mongol warlord Hülegü attacks and destroys the fortress at Alamut. The Assassin library is fully razed, hence destroying a crucial source of information about the Assassins.

- Around 1265: The Assassin strongholds in Syria fall to the Mamluk Sultan Baibars.[10]

According to polemical accounts which would evolve into popular legend, a future assassin was subjected to rites very similar to those of other mystery cults in which the subject was made to believe that he was in imminent danger of death. But the twist of the assassins was that they drugged the person to simulate a "dying" to later have them awaken in a garden flowing with wine and served a sumptuous feast by virgins. The supplicant was then convinced he was in Heaven and that Sabbah was a representative of the divinity and that all of his orders should be followed, even to death. This legend derives from Marco Polo's account on visiting Alamut just after it fell to the Mongols in the thirteenth century.[7][11]

Other accounts of the indoctrination attest that the future assassins were brought to Alamut at a young age and, while they matured, inhabited the aforementioned paradisical gardens and were kept drugged with hashish; as in the previous version, Hassan occupied this garden as a divine emissary. At a certain point (when their initiation could be said to have begun) the drug was withdrawn from them, and they were removed from the gardens and flung into a dungeon. There they were informed that, if they wished to return to the paradise they had so recently enjoyed it would be at Sabbah's discretion, and that they must therefore follow his directions exactly, up to and including murder and self-sacrifice.[11]

Notes

- ^ a b c d Daftari, The Isma'ilis, p. 311.

- ^ Daftari, Farhad (September 2007). "Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period". The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0521616362. "His father, 'Ali b. Muhammad b. Ja'far b. al-Husayn b. Muhammad b. al-Sabbah al-Himyari, a Kufan Arab claiming Yamani origins, had migrated from the Sawad of Kufa to the traditionally Shi'i town of Qumm in Persia."

- ^ Nizam ul-Mulk Tusi, pg. 420, foot note No. 3

- ^ E. G. Brown Literary History of Persia, Vol. 1, pg. 201.

- ^ a b Daftari, The Isma'ilis, pp. 310-11.

- ^ Hassan Sabbah Dabbled in Astronomy: Experts

- ^ a b c http://iranscope.ghandchi.com/Anthology/HassanSabbah.htm

- ^ http://www.rightsidenews.com/2010072411115/world/terrorism/suicide-martyrs-promised-dark-eyed-virgins-in-paradise.html

- ^ a b http://www.unafei.or.jp/english/pdf/PDF_rms/no71/10_p32-p39.pdf

- ^ http://www.shiachat.com/forum/index.php?/topic/34754-hassan-ibn-sabah/

- ^ a b http://www.skewsme.com/assassin.html

See also

References

Secondary sources

- Daftary, Farhad. The Isma'ilis. Their History and Doctrines. 2nd ed (1990). Cambridge et al., 2007.

- Irwin, Robert. "Islam and the Crusades, 1096-1699." In The Oxford History of the Crusades, ed. Jonathan Riley Smith. Oxford, 2002. 211-57.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Hassan-i Sabbah, al-Fuṣūl al-arba'a ("The Four Chapters"), tr. Marshall G.S. Hodgson, in Ismaili Literature Anthology. A Shi'i Vision of Islam, ed. Hermann Landolt, Samira Sheikh and Kutub Kassam. London, 2008. pp. 149–52. Persian treatise on the doctrine of ta'līm. The text is no longer extant, but fragments are cited or paraphrased by al-Shahrastānī and several Persian historians.

- Sargudhasht-i Sayyidnā

- Nizam al-Mulk

- al-Ghazali

Secondary sources

- Daftary, Farhad. A Short History of the Ismailis. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998.

- Daftary, Farhad. The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma'ilis. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 1994. Reviewed by Babak Nahid at Ismaili.net

- Daftary, Farhad. "Hasan-i Sabbāh and the Origins of the Nizārī Ismacili movement." In Mediaeval Ismacili History and Thought, ed. Farhad Daftary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. 181–204.

- Hodgson, Marshall. The Order of Assassins. The Struggle of the Early Nīzarī Ismaīclīs Against the Islamic World. The Hague: Mouton, 1955.

- Hodgson, Marshall. "The Ismacili State." In The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, ed. J.A. Boyle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968. 422–82.

- Lewis, Bernard. The Assassins. A Radical Sect in Islam. New York: Basic Books, 1968.

- Madelung, Wilferd. Religious Trends in Early Islamic Iran. Albany: Bibliotheca Persica, 1988. 101–5.

External links

- The life of Hassan-i-Sabah from an Ismaili point of view. Focuses on assassination as a tactic of asymmetrical warfare and has a small section on Hasan-i-Sabah's work as a scholar.

- Introduction to The Assassin Legends (From The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma‘ilis, London: I. B. Tauris, 1994; reprinted 2001.)

- The life of Hassan-i-Sabbah as part of an online book on the Assassins of Alamut.

- Arkon Daraul on Hassan-i-Sabbah.

- An illustrated article on the Order of Assassins.

- William S. Burrough's invocation of Hassan-i-Sabbah in Nova Express.

- Assassins entry in the Encyclopedia of the Orient.

- Review of the book, "The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma'ilis (I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd: London, 1994), 213 pp." by Babak Nahid, Department of Comparative Literature, University of California, Los Angeles

- Hasan bin Sabbah and the secret order of hashishins

Categories:- 1030s births

- 1124 deaths

- Medieval legends

- People from Qom

- Iranian missionaries

- Iranian Ismailis

- Iranian Muslims

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.