- Great Frigatebird

-

Great Frigatebird Adult male, with inflated gular sac Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Pelecaniformes Family: Fregatidae Genus: Fregata Species: F. minor Binomial name Fregata minor

(Gmelin, 1789)Synonyms Pelecanus minor Gmelin 1789

Tachypetes palmerstoniThe Great Frigatebird (Fregata minor) is a large dispersive seabird in the frigatebird family. Major nesting populations are found in the Pacific (including Galapagos Islands) and Indian Oceans, as well as a population in the South Atlantic.

The Great Frigatebird is a lightly built large seabird up to 105 cm long with predominantly black plumage. The species exhibits sexual dimorphism; the female is larger than the adult male and has a white throat and breast, and the male's scapular feathers have a purple-green sheen. In breeding season, the male is able to distend its striking red gular sac. The species feeds on fish taken in flight from the ocean's surface (mostly flyingfish), and indulges in kleptoparasitism less frequently than other frigatebirds. They feed in pelagic waters within 80 km (50 mi) of their breeding colony or roosting areas.

Contents

Taxonomy

Its scientific name of Fregata minor arose because when it was first discovered, it was thought to be a small pelican, and so named Pelecanus minor by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Gmelin in 1789. Due to the rules of taxonomy, its species name of minor was retained despite being placed in a separate genus. This has led to the discrepancy between minor, Latin for 'smaller' in contrast with its common name. In Hawaii this species is also known as the Iwa (or 'thief' in Hawaiian).[2]

It is one of five closely related species of Frigatebird that make up their own genus (Fregata) and family (Fregatidae). Its closest relative within the group is the Christmas Island Frigatebird (F. andrewsii).

Physical description

The Great Frigatebird is a large seabird and, despite its name, it is the second largest frigatebird, after the Magnificent Frigatebird. The Great Frigatebird measures 85 to 105 centimetres (33 to 41 in) in length with long pointed wings of 205–230 cm (80.5–90.5 in) and long forked tails.[3] The Great Frigatebird weighs from 640–1,550 g (1.4–3.4 lb).[4] The frigatebirds have the highest ratio of wing area to body mass, and the lowest wing loading of any bird. This has been hypothesized to enable the birds to utilize marine thermals created by small differences between tropical air and water temperatures. Male Great Frigatebirds are smaller than females, but the extent of the variation varies geographically.[5] The plumage of males is black with scapular feathers that have a purple-green iridescence when they refract sunlight. Females are black with a white throat and breast and have a red eye ring. Juveniles are black with a rust-tinged white face, head and throat.

Distribution and habitat

The Great Frigatebird has a wide distribution throughout the world’s tropical seas. Hawaii is the northernmost extent of their range in the Pacific Ocean, with around 10,000 pairs nesting mostly in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. In the Central and South Pacific, colonies are found on most islands Groups from Wake Island to the Galapagos Islands to New Caledonia with a few pairs nesting on Australian possessions in the Coral Sea. Colonies are also found on numerous Indian Ocean islands including Aldabra, Christmas Island, Maldives and Mauritius. The small populations in the Western Atlantic Ocean may still persist but are very small if they do. Great Frigatebirds undertake regular migrations across their range, both regular trips and more infrequent widespread dispersals. Birds marked with wing tags on Tern Island in French Frigate Shoals were found to regularly travel to Johnston Atoll (873 km), one was reported in Quezon City in the Philippines.[6] Despite their far ranging birds also exhibit philopatry, breeding in their natal colony even if they travel to other colonies.[7]

Behaviour

Feeding

An immature Great Frigatebird performing a surface snatch on a Sooty Tern chick dropped by another bird

The Great Frigatebird forages in pelagic waters within 80 km (50 mi) of the breeding colony or roosting areas. Flyingfish from the family Exocoetidae are the most common item in the diet of the Great Frigatebird; other fish species and squid may be eaten as well. Prey is snatched while in flight, either from just below the surface or from the air in the case of flyingfish flushed from the water. Great Frigatebirds will make use of schools of predatory tuna or pods of dolphins that push schooling fish to the surface.[8] Like all frigatebirds they will not alight on the water surface and are usually incapable of taking off should accidentally do so.

Great Frigatebirds will also hunt seabird chicks at their breeding colonies, taking mostly the chicks of Sooty Terns, Spectacled Terns, Brown Noddies and Black Noddies. Studies show that only females (adults and immatures) hunt in this fashion, and only a few individuals account for most of the kills.[9]

Great Frigatebirds will attempt kleptoparasitism, chasing other nesting seabirds (boobies and tropicbirds in particular) in order to make them regurgitate their food. This behaviour is not thought to play a significant part of the diet of the species, and is instead a supplement to food obtained by hunting. A study of Great Frigatebirds stealing from Masked Boobies estimated that the frigatebirds could at most obtain 40% of the food they needed, and on average obtained only 5%.[10]

Breeding

Great Frigatebirds are seasonally monogamous, with a breeding season that can take two years from mating to the end of parental care. The species is colonial, nesting in bushes and trees (and on the ground in the absence of vegetation) in colonies of up to several thousand pairs. Nesting bushes are often shared with other species, especially Red-footed Boobies and other species of frigatebirds.

Both sexes have a patch of red skin at the throat that is the gular sac; in male Great Frigatebirds this is inflated in order to attract a mate. Groups of males sit in bushes and trees and force air into their sac, causing it to inflate over a period of 20 minutes into a startling red balloon. As females fly overhead the males waggle their heads from side to side, shake their wings and call. Females will observe many groups of males before forming a pair bond. Having formed a bond the pair will sometimes select the display site, or may seek another site, to form a nesting site; once a nesting site has been established both sexes will defend their territory (the area surrounding the nest that can be reached from the nest) from other frigatebirds.

Pair bond formation and nest-building can be completed in a couple of days by some pairs and can take a couple of weeks (up to four) for other pairs. Males collect loose nesting material (twigs, vines, flotsam) from around the colony and off the ocean surface and return to the nesting site where the female builds the nest. Nesting material may be stolen from other seabird species (in the case of Black Noddies the entire nest may be stolen) either snatched off the nesting site or stolen from other birds themselves foraging for nesting material. Great Frigatebird nests are large platforms of loosely woven twigs that quickly become encrusted with guano. There is little attempt to maintain the nests during the breeding season and nests may disintegrate before the end of the season.

A single dull chalky-white egg measuring 68 x 48 mm is laid during each breeding season.[11] If the egg is lost the pair bond breaks; females may acquire a new mate and lay again in that year. Both parents incubate the egg in shifts that last between 3–6 days; the length of shift varies by location, although female shifts are longer than those of males. Incubation can be energetically demanding, birds have been recorded losing between 20–33% of their body mass during a shift.

Incubation lasts for around 55 days. Great Frigatebird chicks begin calling a few days before hatching and rub their egg tooth against the shell. The altricial chicks are naked and helpless, and lie prone for several days after hatching. Chicks are brooded for two weeks after hatching after which they are covered in white down, and guarded by a parent for another fortnight after that. Chicks are given numerous meals a day after hatching, once older they are fed every one to two days. Feeding is by regurgitation, the chick sticks its head inside the adults mouth.

Parental care is prolonged in Great Frigatebirds. Fledging occurs after 4–6 months, the timing dependent on oceanic conditions and food availability.[3] After fledging chicks continue to receive parental care for between 150–428 days; frigatebirds have the longest period of post-fledging parental care of any bird. The length of this care depends on oceanic conditions, in bad years (particularly El Niño years) the period of care is longer. The diet of these juvenile birds is provided in part by food they obtained for themselves and in part from their parents. Young fledglings will also engage in play; with one bird picking up a stick and being chased by one or more other fledglings. After the chick drops the stick the chaser attempts to catch the stick before it hits the water, after which the game starts again. This play is thought to be important in developing the aerial skills needed to fish.

References

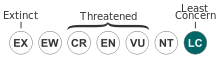

- ^ BirdLife International (2004). Fregata minor. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 12 May 2006. Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- ^ John L. Eliot & Jonathan Blair (1978). "Hawaii's Far-flung Wildlife Paradise". National Geographic (National Geographic Society) 153 (5): 679. ISSN 0027-9358.

- ^ a b Metz, V. G., & E. A. Schreiber. (2002). Great Frigatebird (Fregata minor). In The Birds of North America, No. 681 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0849342585.

- ^ Schreiber E & Schreiber R (1988) " Great Frigatebird Size Dimorphism on Two Central Pacific Atolls" Condor 90(1): 90–99.

- ^ Dearborn, D., Anders, A., Schreiber, E., Adams, R. & Muellers, U. (2003) “Inter Island movements and population differentiation in a pelagic seabird” Molecular Ecology 12: 2835-2843

- ^ Harrison C. (1990). Seabirds of Hawaii: natural history and conservation. Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, NY. ISBN 0-8014-2449-6

- ^ Au, D.W.K. & Pitman, R.L. (1986) Seabird interactions with Dolphins and Tuna in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. Condor, 88: 304-317. [1]

- ^ Megyesi JL, Griffin CR (1996) "Brown noddy chick predation by great frigatebirds in the northwestern Hawaiian islands" Condor 98(2): 322-327

- ^ Vickery, J & Brooke, M. (1994) "The Kleptoparasitic Interactions between Great Frigatebirds and Masked Boobies on Henderson Island, South Pacific " Condor 96: 331-340

- ^ Beruldsen, G (2003). Australian Birds: Their Nests and Eggs. Kenmore Hills, Qld: self. pp. 186–87. ISBN 0-646-42798-9.

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Birds of Australia

- Birds of Africa

- Birds of India

- Fregata

- Birds of Palau

- Birds of the Cook Islands

- Animals described in 1789

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.