- Algerian mouse

-

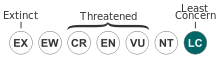

Algerian mouse Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Rodentia Family: Muridae Genus: Mus Species: M. spretus Binomial name Mus spretus

Lataste, 1883Subspecies Mus spretus spretus

Mus spretus parvusSynonyms Mus spicilegus spretus

The Algerian mouse, or western Mediterranean mouse, (Mus spretus) is a wild species of mouse closely related to the house mouse, native to open habitats around the western Mediterranean.

Contents

Description

The Algerian mouse closely resembles the house mouse in appearance, and can be most easily distinguished from that species by its shorter tail. It has brownish fur over most of the body, with distinct white or buff underparts. It ranges from 7.9 to 9.3 centimetres (3.1 to 3.7 in) in head-body length with a 5.9 to 7.3 centimetres (2.3 to 2.9 in) tail and a body weight of 15 to 19 grams (0.53 to 0.67 oz).[2]

Distribution and habitat

The Algerian mouse inhabits south-western Europe and the western Mediterranean coast of Africa. It is found throughout mainland Portugal, and in all but the most northerly parts of Spain. Its range extends east of the Pyrenees into southern France, where it is found in south-eastern regions around Toulouse and up the Rhone valley to Valence. It is also found throughout the Balearic Islands. In Africa, it is found in the Maghreb regions of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and western Libya, north of the Sahara desert. There is also a small population on the coast of eastern Libya.[1]

It prefers open terrain, avoiding dense forests, and being most commonly found in temperate grassland, arable land, and rural gardens. It can typically be found in areas of grassland or open scrub, where shrubs and tall grasses can help obscure it from predators, but where plenty of open ground is available. Although it is considered a fully wild species, avoiding humans, it may occasionally be found in abandoned buildings.[2]

Behaviour and ecology

The Algerian mouse is primarily nocturnal. It is an opportunistic omnivore, primarily feeding on grass seeds, fruit, and insects. It has been reported to require only two thirds the volume of drinking water required by the house mouse. As a relatively unspecialised small mammal, it is preyed on by a number of predators, including owls, mammalian carnivores, and snakes.[2]

Adult males range across a territory of around 340 square metres (3,700 sq ft), which overlap with the ranges of neighbouring females, but not with those of other males.[3] Although they defend at least the core areas of their ranges from other mice, they are less aggressive than house mice, establishing dominance through ritual behaviour rather than overt violence.[4] The mice have been reported to clear away their own faeces from areas they regularly inhabit or use, either by picking up the droppings in their mouths or pushing them along the ground with their snouts. This hygienic behaviour is notably different from that of the closely related house mouse.[5]

Reproduction

Algerian mice breed for nine months of the year, but are sexually inactive from November to January. Although they can breed during any other month, they have two breeding seasons during which they are particularly active. In April and May, adults surviving from the previous year produce a new generation of mice, then both they and their new offspring breed during the second peak in August to September. Gestation lasts 19 to 20 days, and results in the birth of two to ten blind and hairless pups, with about five being average.[2]

The young begin to develop fur at two to four days, their ears open at three to five days, and their eyes open at twelve to fourteen. The young begin to eat solid food as soon as they are able to see, but are not fully weaned for about three or four weeks, leaving the nest shortly thereafter. They reach the full adult size at eight to nine weeks, by which time they are already sexually mature They have been reported to live for up to fifteen months.[2]

Hybridization

Biologist Michael Kohn of Rice University in Houston, Texas and his associate believed that they "caught evolution in the act" while studying mice resistant to warfarin in a German bakery. Genetic study revealed that the supposed house mice carried a significant amount of Algerian mouse DNA in their chromosomes and a gene (VKOR, which has been thought to appear first in Mus spretus and perpetuate because it has helped the mice to survive while eating vitamin K-deficient diets) that confers resistance to warfarin. The discovery was believed to have evolutionary importance because this was the first time hybridization had been shown to result in a positive consequence. The discovery was published in the journal Current Biology in July 2011.[6][7]

Taxonomy and evolution

There are four recognised species of the genus Mus native to Europe. Mus musculus is the house mouse, which primarily inhabits human dwellings and other structures, although it may occasionally return to the wild as feral populations. The Algerian mouse is one of the three remaining wild species; although its exact relationship to the house mouse is unclear, it may represent the earliest evolutionary divergence within the group.[8]

In any event, it is sufficiently closely related that male house mice can breed with female Algerian to produce viable offspring, although this has only been observed in captivity, and does not appear to occur in the wild, perhaps because the two species inhabit different habitats. Male hybrids of these unions are sterile, but female hybrids are not. In contrast, male Algerian mice do not breed with female house mice, violently driving them away.[2]

The oldest fossils of the species date back 40,000 years, and were found in Morocco[2]. Along with evidence based on modern genetic diversity, this suggests that the species first arose in Africa, and only later migrated north to Europe, perhaps with the expansion of agricultural land into the continent during the Neolithic.[9]

References

- ^ a b Amori, G., Aulagnier, S., Hutterer, R., Kryštufek, B., Yigit, N., Mitsain, G. & Muñoz, L.J.P (2008). Mus spretus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 23 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Palomo, L.J. et al. (2009). "Mus spretus (Rodentia:Muridae)". Mammalian Species 840: 1–10. doi:10.1644/840.1.

- ^ Gray, S.J. et al. (1998). "Microhabitat and spatial dispersion of the grassland mouse (Mus spretus Lataste)". Journal of Zoology 246 (3): 299–308. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00160.x.

- ^ Hurst, J.L. et al. (1997). "Social interaction alters attraction to competitor's odour in the mouse Mus spretus Lataste". Animal Behaviour 54 (4): 941–953. doi:10.1006/anbe.1997.0515.

- ^ Hurst, J.L. & Smith, J. (1995). "Mus spretus Lataste: a hygienic house mouse?". Animal Behaviour 49 (3): 827–834. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(95)80214-2.

- ^ http://news.discovery.com/animals/super-mouse-poison-resistant-110721.html#mkcpgn=emnws1

- ^ http://news.sciencemag.org/sciencenow/2011/07/bastard-mouse-steals-poison-resi.html

- ^ Lundrigan, B.L. et al. (2002). "Phylogenetic relationships in the genus Mus, based on paternally, maternally and biparentally inherited characters". Systematic Biology 51 (3): 410–431. doi:10.1080/10635150290069878.

- ^ Gippoliti, S. & Amori, G. (2006). "Ancient introductions of mammals in the Mediterranean Basin and their implications for conservation". Mammal Review 36 (1): 37–48. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2006.00081.x.