- United States presidential line of succession

-

The United States presidential line of succession defines who may become or act as President of the United States upon the incapacity, death, resignation, or removal from office (by impeachment and subsequent conviction) of a sitting president or a president-elect.

Current order

This is a list of the current presidential line of succession,[1] as specified by the United States Constitution and the Presidential Succession Act of 1947[2] as subsequently amended to include newly created cabinet offices.

# Office Current officer President of the United States Barack Obama (D) 1 Vice President of the United States Joe Biden (D) 2 Speaker of the House John Boehner (R) 3 President pro tempore of the Senate Daniel Inouye (D) 4 Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton (D) 5 Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner (I)[3] 6 Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta (D) 7 Attorney General Eric Holder (D) 8 Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar (D) 9 Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack (D) 10 Secretary of Commerce John Bryson (D) 11 Secretary of Labor Hilda Solis (D) 12 Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius (D) 13 Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Shaun Donovan (D) 14 Secretary of Transportation Ray LaHood (R) 15 Secretary of Energy Steven Chu (D) 16 Secretary of Education Arne Duncan (D) 17 Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki* 18 Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano (D) *Eric Shinseki, the Secretary of Veterans Affairs, is not known to have declared a party affiliation.

Eligibility

Eligibility requirements

No person is eligible to be President, unless that person is a natural-born citizen, is at least thirty-five years old, and has been a resident within the United States for at least fourteen years. These eligibility requirements are specified both in the U.S. Constitution, Article II, Section 1, Clause 5, and in the Presidential Succession Act ().

Acting officers

Acting officers may be eligible. In 2009, the Continuity of Government Commission, a private non-partisan think tank, reported,

“ The language in the current Presidential Succession Act is less clear than that of the 1886 Act with respect to Senate confirmation. The 1886 Act refers to "such officers as shall have been appointed by the advice and consent of the Senate to the office therein named..." The current act merely refers to "officers appointed, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate." Read literally, this means that the current act allows for acting secretaries to be in the line of succession as long as they are confirmed by the Senate for a post (even for example, the second or third in command within a department). It is not uncommon for a second in command to become acting secretary when the secretary leaves office. Though there is some dispute over this provision, the language clearly permits acting secretaries to be placed in the line of succession. (We have spoken to acting secretaries who told us they had been placed in the line of succession.)[4] ” Motivation for changes to the succession in 1945

Two months after succeeding Franklin D. Roosevelt, President Harry S. Truman proposed that the Speaker of the House and the President pro tempore of the Senate be granted priority in the line of succession over the Cabinet so as to ensure the President would not be able to appoint his successor to the Presidency.[5]

The Secretary of State is appointed by the President, while the Speaker of the House and the President pro tempore of the Senate are elected officials. The Speaker is chosen by the U.S. House of Representatives, and every Speaker has been a member of that body for the duration of their term as Speaker; the President pro tempore is chosen by the U.S. Senate and by custom the Senator of the majority party with the longest record of continuous service fills this position. The Congress approved this change and inserted the Speaker and the President pro tempore in line, ahead of the members of the Cabinet in the order in which their positions were established.

Some of Truman's critics said that his ordering of the Speaker before the President pro tempore was motivated by his dislike of the then-current holder of the latter rank, Senator Kenneth McKellar.[6] Further motivation may have been provided by Truman's preference for House Speaker Sam Rayburn to be next in the line of succession, rather than Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius, Jr.

In his speech supporting the changes, Truman noted that the House is more likely to be in political agreement with the President and Vice President than the Senate. The succession of a Republican to a Democratic Presidency would further complicate an already unstable political situation. However, when the changes to the succession were signed into law, they placed Republican House Speaker Joseph W. Martin first in the line of succession after the Vice President.[7]

Constitutional foundation

The line of succession is mentioned in three places in the Constitution: in Article II, Section 1, in Section 3 of the 20th Amendment, and in the 25th Amendment.

- Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 makes the Vice President first in the line of succession and allows the Congress to provide by law for cases in which neither the President nor Vice President can serve. The current such law governing succession is the Presidential Succession Act of 1947 (3 U.S.C. § 19).

- Section 3 of the 20th Amendment provides that if the President-elect dies before his term begins, the Vice President-elect becomes President on Inauguration Day and serves for the full term to which the President-elect was elected. The section also provides that if, on Inauguration Day, a president has not been chosen or the President-elect does not qualify for the presidency, the Vice President-elect acts as president until a president is chosen or the President-elect qualifies. Finally, Section 3 allows the Congress to provide by law for cases in which neither a President-elect nor a Vice President-elect is eligible or available to serve.

- The 25th Amendment, ratified in 1967, clarified Article II, Section 1: that the Vice President is the direct successor of the President. He or she becomes President if the President dies, resigns or is removed from office. The 25th also provides for the situation where the President is temporarily disabled, such as if the President has a surgical procedure or becomes mentally unstable. It also required vice presidential vacancies to be filled by the President and confirmed by Congress. Previously, when a vice president had succeeded to the presidency or otherwise left the office empty (through death, resignation, or removal from office), the vice presidency remained vacant until the next presidential election.

Acting President and President

Main article: Acting President of the United States New President Lyndon Johnson was sworn in aboard Air Force One, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963.

New President Lyndon Johnson was sworn in aboard Air Force One, following the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963.

Article II, Section 1 of the United States Constitution provides that:

- In case of the removal of the President from office, or of his death, resignation, or inability to discharge the powers and duties of the said office, the same shall devolve on the Vice President ... until the disability be removed, or a President elected.

This originally left open the question whether "the same" refers to "the said office" or only "the powers and duties of the said office". Some historians, including Edward Corwin[8] and John D. Feerick,[8] have argued that the framers' intention was that the Vice President would remain Vice President while executing the powers and duties of the presidency; however, there is also much evidence to the contrary, the most compelling of which is Article I, section 3, of the Constitution itself, the relevant text of which reads:

- The Vice President of the United States shall be President of the Senate, but shall have no vote, unless they be equally divided.

- The Senate shall choose their other officers, and also a President pro tempore, in the absence of the Vice President, or when he shall exercise the office of President of the United States.

This text appears to answer the hypothetical question of whether the office or merely the powers of the presidency devolved upon the Vice President on his succession. Thus, the 25th Amendment merely restates and reaffirms the validity of existing precedent, apart from adding valuable new protocols for presidential disability. Not everyone agreed with this interpretation when it was first put to the test, and it was left to John Tyler, the first presidential successor in U.S. history, to establish the precedent that was respected in the absence of the 25th Amendment.

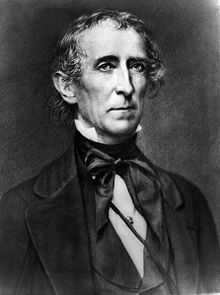

In 1841, John Tyler became the first person to succeed to the presidency.

In 1841, John Tyler became the first person to succeed to the presidency.

Upon the death of President William Henry Harrison in 1841, after a brief hesitation, Vice President John Tyler took the position that he was President, and not merely acting President, upon taking the presidential oath of office. However, some contemporaries—including John Quincy Adams,[8][9] Henry Clay[10] and other members of Congress,[9][10] Whig party leaders,[10] and even Tyler's own cabinet[9][10]—believed that he was only acting as president, and did not have the office itself.

Nonetheless, Tyler adhered to his position, even returning unopened mail addressed to the "Acting President of the United States" sent by his detractors.[11] Tyler's view ultimately prevailed when the Senate voted to accept the title "President,"[10] and this precedent was followed thereafter. The question was finally resolved by Section 1 of the 25th Amendment which specifies that: "In case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation, the Vice President shall become President." The Amendment does not specify whether officers other than the Vice President can become President rather than Acting President in the same set of circumstances. However, the Presidential Succession Act makes clear that anyone who takes office under its provisions shall only "act as President"—even if they "act" in that role for years. Thus only someone serving as Vice President can ever succeed to the title of "President of the United States."

History of succession law set by Congress

Main article: Presidential Succession ActThe Presidential Succession Act of 1792 was the first succession law passed by Congress. The act was contentious because of conflict between the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists did not want the Secretary of State to appear next on the list after the Vice President because Thomas Jefferson was then Secretary of State and had emerged as a Democratic-Republican leader. There were also concerns about including the Chief Justice of the United States since that would go against the separation of powers. The compromise that was worked out established the President pro tempore of the Senate as next in line of succession after the Vice President, followed by the Speaker of the House of Representatives. In either case, these officers were to "act as President of the United States until the disability be removed or a president be elected." The Act called for a special election to be held in November of the year in which dual vacancies occurred (unless the vacancies occurred after the first Wednesday in October, in which case the election would occur the following year; or unless the vacancies occurred within the last year of the presidential term, in which case the next election would take place as regularly scheduled). The people elected President and Vice President in such a special election would have served a full four-year term beginning on March 4 of the next year, but no such election ever took place.

In 1881, after the death of President Garfield, and in 1885, after the death of Vice President Hendricks, there had been no President pro tempore in office, and as the new House of Representatives had yet to convene, no Speaker either,[12] leaving no one at all in the line of succession after the vice president. When Congress convened in December 1885, President Cleveland asked for a revision of the 1792 act.

This was passed in 1886. Congress replaced the President pro tempore and Speaker with officers of the President's Cabinet with the Secretary of State first in line. In the first 100 years of the United States, six former Secretaries of State had gone on to be elected President, while only two Congressional leaders had advanced to that office. As a result, shuffling the order of the line of succession seemed reasonable.[citation needed]

The Presidential Succession Act of 1947, signed into law by President Harry S. Truman, added the Speaker of the House and President pro tempore back in the line, but switched the two from the 1792 order. It remains the sequence used today[update]. Since the reorganization of the military in 1947 had merged the War Department (which governed the Army) with the Department of the Navy into the Department of Defense, the Secretary of Defense took the place in the order of succession previously held by the Secretary of War. The office of Secretary of the Navy, which had existed as a Cabinet-level position since 1798, had become subordinate to the Secretary of Defense in the military reorganization, and so was dropped from the line of succession in the 1947 Succession Act.

Until 1971, the Postmaster General, the head of the Post Office Department, was a member of the Cabinet, initially the last in the presidential line of succession before new officers were added. Once the Post Office Department was re-organized into the United States Postal Service, a special agency independent of the executive branch, the Postmaster General ceased to be a member of the Cabinet and was thus removed from the line of succession.

The order of Cabinet members set out in the statute has always been the same as the order in which their respective departments were established. However, when the United States Department of Homeland Security was created in 2002, many in Congress wanted the Secretary to be placed at number eight on the list – below the Attorney General, above the Secretary of the Interior, and in the position held by the Secretary of the Navy prior to the creation of the Secretary of Defense – because the Secretary, already in charge of disaster relief and security, would presumably be more prepared to take over the presidency than some of the other Cabinet secretaries. Legislation to add the Secretary of Homeland Security to the bottom of the list was enacted on March 9, 2006.

Successions beyond Vice President

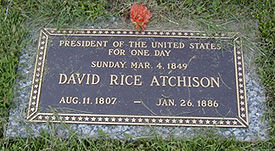

David Rice Atchison's tombstone, Plattsburg, Missouri, including the claim "President of the United States for One Day"

David Rice Atchison's tombstone, Plattsburg, Missouri, including the claim "President of the United States for One Day"

While nine vice presidents have succeeded to the office upon the death or resignation of the President, and two vice presidents have temporarily served as acting President, no other officer has ever been called upon to act as President.

On March 4, 1849, James K. Polk's presidency ended on a Sunday. President-elect Zachary Taylor declined to be sworn in on a Sunday, citing religious beliefs. Senate President pro tempore David Rice Atchison's tombstone states that he was President for the day. However, given that the last day of Atchison's own term as Senate President pro tempore was March 3, that claim seems dubious. Indeed, since Atchison took no oath of office to the presidency, it is not logical to label Atchison as a president on the basis of Taylor's merely not taking the oath.

In 1865, when Andrew Johnson assumed the presidency on the death of Abraham Lincoln, the office of Vice President became vacant. At that time, the Senate President pro tempore was next in line to the presidency. In 1868 Johnson was impeached, and if he had been removed from office, President pro tempore Benjamin Wade would have become acting President. This posed a conflict of interest, as Wade's own vote on removal could have helped to determine whether he would succeed to the presidency.

During the 1973 vice-presidential vacancy, House Speaker Carl Albert was first in line. As the Watergate scandal made President Nixon's removal or resignation possible, Albert would have become Acting President and—under Title 3, Section 19(c) of the U.S. Code—would have been able to "act as President until the expiration of the then current Presidential term." Albert openly questioned whether it was appropriate for him, a Democrat, to assume the powers and duties of the presidency when there was a public mandate for the presidency to be held by a Republican. Albert announced that should he need to assume the presidential powers and duties, he would do so only as a caretaker. However, with the nomination and confirmation of Gerald Ford to the vice presidency, these series of events were never tested. Albert again became first-in-line during the first four months of Ford's presidency, before the confirmation of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller.

In 1981, when President Ronald Reagan was shot, Vice President George H. W. Bush was traveling in Texas. Secretary of State Alexander Haig responded to a reporter's question regarding who was running the government by stating;

“ Constitutionally, gentlemen, you have the President, the Vice President and the Secretary of State in that order, and should the President decide he wants to transfer the helm to the Vice President, he will do so. He has not done that. As of now, I am in control here, in the White House, pending return of the Vice President and in close touch with him. If something came up, I would check with him, of course.[13] ” A bitter dispute ensued over the meaning of Haig's remarks. Most people believed that Haig was referring to the line of succession and erroneously claimed to have temporary presidential authority, due to his reference to the Constitution. Haig and his supporters, noting his familiarity with the line of succession from his time as White House Chief of Staff during Richard Nixon's resignation, said he only meant that he was the highest ranking officer of the Executive branch on-site, managing things temporarily until the Vice President returned to Washington.

Constitutional concerns

Several constitutional law experts have raised questions as to the constitutionality of the provisions that the Speaker of the House and the President pro tempore of the Senate succeed to the presidency.[14] James Madison, one of the authors of the Constitution, raised similar constitutional questions about the Presidential Succession Act of 1792 in a 1792 letter to Edmund Pendleton.[15] Two of these issues can be summarized:

- The term "Officer" in the relevant clause of the Constitution is most plausibly interpreted to mean an "Officer of the United States", who must be a member of the Executive or Judicial Branch. The Speaker and the President pro tempore are not officers in this sense.

- Under the principle of separation of powers, the Constitution specifically disallows legislative officials from also serving in the executive branch. For the Speaker or the Senate President pro tempore to become Acting President, they must resign their position, at which point they are no longer in the line of succession. This forms a constitutional paradox to some.

In 2003 the Continuity of Government Commission suggested that the current law has "at least seven significant issues ... that warrant attention", including:[16]

- The reality that all figures in the current line of succession work and reside in the vicinity of Washington, D.C. In the event of a nuclear, chemical, or biological attack, it is possible that everyone on the list would be killed or incapacitated.

- Doubt (such as those expressed above by James Madison) that Congressional leaders are eligible to act as President.

- A concern about the wisdom of including the President pro tempore in the line of succession as the "largely honorific post traditionally held by the longest-serving Senator of the majority party". For example, from January 20, 2001, to June 6, 2001, the President pro tempore was then-98-year-old Strom Thurmond of South Carolina.

- A concern that the current line of succession can force the presidency to abruptly switch parties mid-term, as the Speaker and the President pro tempore are not necessarily of the same party as the President.

- A concern that the succession line is ordered by the dates of creation of the various executive departments, without regard to the skills or capacities of the persons serving as their Secretary.

- The fact that, should a Cabinet member begin to act as President, the law allows the House to elect a new Speaker (or the Senate, a new President pro tempore), who could in effect remove the Cabinet member and assume the office themselves at any time.

- The absence of a provision where a President is disabled and the vice presidency is vacant (for example, if an assassination attempt simultaneously wounded the President and killed the Vice President).

See also

- Designated survivor

- Fiction regarding United States presidential succession

- List of United States presidential assassination attempts and plots

References

- ^ "Presidential Succession: Perspectives, Contemporary Analysis, and 110th Congress Proposed Legislation (RL34692)" (pdf). Congressional Research Service. October 3, 2008. p. 27. http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/RL34692_20081003.pdf.

- ^ 3 U.S.C. § 19

- ^ Raum, Tom (18 October 2008). "Next treasury boss will feel power - and stress". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/money/economy/2008-10-17-2159631534_x.htm. Retrieved November 25, 2010.

- ^ "Preserving Our Institutions: Presidential Succession," Continuity of Government Commission, June 2009, p.34

- ^ "Special Message to the Congress on the Succession to the Presidency. June 19, 1945" by President Harry S. Truman; from the American Presidency Project archives

- ^ Kipnotes.com

- ^ Wildavsky, Aaron B. (2003). Horowitz, Irving. ed (in Rnglish) (Google Books). The revolt against the masses and other essays on politics and public policy. Transaction Publishers. p. 122. ISBN 9780765809605. http://books.google.com/?id=hWT0JOgzHRgC&pg=PA446&dq=9780765809605. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- ^ a b c Schlesinger, Arthur M., Jr. (Autumn, 1974). "On the Presidential Succession". Political Science Quarterly 3 (3): 475, 495–496. JSTOR 2148451.

- ^ a b c Rankin, Robert S. (Feb. 1946). "Presidential Succession in the United States". The Journal of Politics 8 (1): 44, 45. JSTOR 2125607.

- ^ a b c d e Abbott, Philip (Dec. 2005). "Accidental Presidents: Death, Assassination, Resignation, and Democratic Succession". Presidential Studies Quarterly 35 (4): 627, 638. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2005.00269.x. JSTOR 27552721.

- ^ Crapol, Edward P. (2006). John Tyler: the accidental president. UNC Press Books. p. 10. ISBN 9780807830413. OCLC 469686610.

- ^ Lewis, Charlton Thomas; Willsey, Joseph H. (1895). Harper's Book of Facts: a Classified History of the World; Embracing Science, Literature, and Art. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 884. LCCN 01-20386. http://books.google.com/books?id=UcwGAAAAYAAJ&lpg=PA884&dq=why%20did%20cleveland%20change%20line%20of%20succession%201885&pg=PA884#v=snippet&q=country%20without%20any%20one%20in%20the%20line%20of%20succession&f=false. Retrieved 24 Apr 2011.

- ^ Alexander Haig, Time Magazine, April 02, 1984

- ^ "Is the Presidential Succession Law Constitutional?", Akhil Reed Amar, Stanford Law Review, November 1995.

- ^ uchicago.edu

- ^ First Report p. 4, continuityofgovernment.org Retrieved December 28, 2010 via Internet Archive to repair dead link

Further reading

- Ask Gleaves: Presidential Succession from the website of Grand Valley State University

- 3 U.S.C. § 19 - "Vacancy in offices of both President and Vice President; officers eligible to act"

- Presidential Succession Act of 1792, 1 Stat. 239 (from the American Memory website of the Library of Congress

- "Presidential Line of Succession Examined", a September 20, 2003 article from the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

- "WI Presidential Succession Act of 1947 held unconstitutional", David Tenner, Usenet group: soc.history.what-if, January 14, 2003.

- Fools, Drunkards, & Presidential Succession from the Federalist Society website

- Official website of the Continuity of Government Commission

- October 2003 Hearings before the Continuity of Government Commission

- Testimony of M. Miller Baker from the U.S. Senate website

External links

- The Presidency: Preserving Our Institutions Second report of the Continuity of Government Commission, June 2009 (includes the text of the Presidential Succession Acts of 1792, 1886 and 1947)

Lists relating to Presidents of the United States and Vice Presidents of the United States Presidential lists by order Professional careers - Political affiliation

- Other offices held

- Elected office

- Executive experience

- Inaugurations

- Doctrines

- International trips

- Judicial appointments

- Pardons

- Vetoes

- Control of Congress

- Assassination attempts and plots

- Libraries

- Campaign slogans

- Currency appearances

- U.S. postage stamp appearances

Personal life - Nicknames

- Names

- Genealogical relationship

- Education

- Military service

- Pets

- Place of birth

- Place of primary affiliation

- Previous occupation

- Religious affiliation

- Residences

- Summer White Houses

- Languages

- Handedness

- Deaths in office

Vice presidential lists - Order of service

- Time in office

- Age of ascension

- Other offices held

- Birth

- Tie-breaking votes

- Death and longevity

- Vacancies

- Place of primary affiliation

- Religious affiliation

- Education

Succession - Line of succession

- Designated survivor

Elections Candidates - 1789–1852

- 1856–present

- Democratic tickets

- Republican tickets

- Height

- African American

- Female

- Lost their home state

- Former presidents who ran again

- All candidates with at least one electoral vote

In fiction - Presidents

- Vice Presidents

- Candidates

- Succession

Families - First Family

- First ladies (List

- Number living)

- Second ladies

- Children

Orders of succession Monarchies Bahrain · Belgium · Bhutan · Brunei · Cambodia · Denmark · Japan · Jordan · Kuwait · Lesotho · Liechtenstein · Luxembourg · Malaysia · Monaco · Morocco · Netherlands · Norway · Oman · Qatar · Saudi Arabia · Spain · Swaziland · Sweden · Thailand · Tonga · United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realmsPresidencies Categories:- United States presidential succession

- Vice Presidency of the United States

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.