- Common chimpanzee

-

Common chimpanzee[1]

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Hominidae Tribe: Hominini Genus: Pan Species: P. troglodytes Binomial name Pan troglodytes

(Blumenbach, 1776)

distribution of common chimpanzee. 1. Pan troglodytes verus. 2. P. t. ellioti. 3. P. t. troglodytes. 4. P. t. schweinfurthii. Synonyms Simia troglodytes Blumenbach, 1776

Troglodytes troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1776)

Troglodytes niger E. Geoffroy, 1812

Pan niger (E. Geoffroy, 1812)The common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), also known as the robust chimpanzee, is a great ape. Colloquially, the common chimpanzee is often called the chimpanzee (or simply 'chimp'), though technically this term refers to both species in the genus Pan: the common chimpanzee and the closely related bonobo, formerly called the pygmy chimpanzee. Evidence from fossils and DNA sequencing show that both species of chimpanzees are the sister group to the modern human lineage. The common chimpanzee is an endangered species.

Contents

Study

Naming

The name troglodytes, Greek for "cave-dweller" , was coined by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in his book De generis hvmani varietate nativa liber ("Book on the natural varieties of the human genus") published in 1776,[3][4] This book was based on his dissertation presented one year before (it had a date 16 Sep 1775 printed on its title page) to the University of Göttingen for internal use only,[5] thus the dissertation did not meet the conditions for published work in the sense of zoological nomenclature.[6]

The English name 'chimpanzee' came from a Bantu language of Angola. [7]

Field study

Jane Goodall undertook the first long-term field study of the common chimpanzee, begun in Tanzania at Gombe Stream National Park in 1960. Other long-term study sites begun in 1960 include A. Kortlandt in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and Junichiro Itani in Mahale Mountains National Park in Tanzania.[8] Current understanding of the species' typical behaviors and social organization are formed largely from Goodall's ongoing 50-year Gombe research study.[9]

Fossils

A lot of human fossils have been found, but chimpanzee fossils were not described until 2005. Existing chimpanzee populations in West and Central Africa do not overlap with the major human fossil sites in East Africa. However, chimpanzee fossils have now been reported from Kenya. This would indicate that both humans and members of the Pan clade were present in the East African Rift Valley during the Middle Pleistocene. According to Richard Dawkins in his book The Ancestor's Tale, chimps and bonobos are descended from Australopithecus. Gracile type species (see Homininae), in other words, the ancestors of chimpanzees would be some of the Australopithecus afarensis.

Taxonomy

DNA evidence published in 2005 suggests the bonobo and common chimpanzee species separated from each other less than one million years ago (similar in relation between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals).[10][11] The chimpanzee line split from the last common ancestor of the human line approximately six million years ago. Because no species other than Homo sapiens has survived from the human line of that branching, both chimpanzee species are the closest living relatives of humans. The chimpanzee's genus, Pan, diverged from the gorilla's genus about seven million years ago.

Subspecies

Several subspecies of the common chimpanzee have been recognized:

- Central chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes troglodytes, in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo;

- Western chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus, in Guinea, Mali, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria;

- Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes ellioti, in Nigeria and Cameroon;

- Eastern chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, in the Central African Republic, the Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, and Zambia.

Genome Project

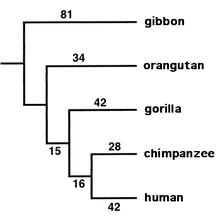

Main article: Chimpanzee Genome Project Relationships among apes. The numbers in this diagram are branch lengths, a measure of evolutionary distinctness. Based on protein electrophoresis data of Goldman et al., PNAS 84: 3307-3311 [12]

Relationships among apes. The numbers in this diagram are branch lengths, a measure of evolutionary distinctness. Based on protein electrophoresis data of Goldman et al., PNAS 84: 3307-3311 [12]

Human and common chimpanzee DNA are very similar. After the completion of the Human Genome Project, a Chimpanzee Genome Project was initiated. In December 2003, a preliminary analysis of 7600 genes shared between the two genomes confirmed that certain genes, such as the forkhead-box P2 transcription factor which is involved in speech development, have undergone rapid evolution in the human lineage. A draft version of the chimpanzee genome was published on September 1, 2005, in an article produced by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium.[13] The DNA sequence differences between humans and chimpanzees is about thirty-five million single-nucleotide changes, five million insertion/deletion events, and various chromosomal rearrangements. Typical human and chimp protein homologs differ in only an average of two amino acids. About 30% of all human proteins are identical in sequence to the corresponding chimp protein. Duplications of small parts of chromosomes have been the major source of differences between human and chimp genetic material; about 2.7% of the corresponding modern genomes represent differences, produced by gene duplications or deletions, during the approximately four to six million years since humans and chimps diverged from their common evolutionary ancestor. Results from human and chimp genome analyses, currently being conducted by geneticists including David Reich, should help in understanding the genetic basis of some human diseases.

Description

Adults in the wild weigh between 40 and 65 kg (88 and 140 lb), though males in captivity such as Travis the Chimp have reached 200 pounds; males can measure up to 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) and females to 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in). Their body is covered by a coarse black hair, except for the face, fingers, toes, palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Both their thumbs and their big toes are opposable, allowing a precision grip. Their gestation period is eight months. Infants are weaned when they are about three years old, but usually maintain a close relationship with their mother for several more years; they reach puberty at the age of eight to ten, and their lifespan in captivity is about fifty years. Common chimpanzees are both arboreal and terrestrial, spending equal time in the trees and on the ground.[citation needed] Their habitual gait is quadrupedal, using the soles of their feet and resting on their knuckles, but they can walk upright for short distances. Common chimpanzees are 'knuckle walkers', like gorillas and bonobos, in contrast to the quadrupedal locomotion of orangutans, 'palm walkers' who use the outside edge of their palms.

Ecology

The common chimpanzee is a highly adaptable species. They live in a variety of habitats, including: dry savanna, evergreen rainforest, montane forest, swamp forest, and dry woodland-savanna mosaic.[14][15] In Gombe chimps live in subalpine moorland, open woodland, semideciduous forest, evergreen forest, grassland with scattered trees.[15] At Bossou, chimpanzee inhabit multi-stage secondary deciduous forest arising in areas abandoned due to shifting agriculture. They also live in primary forest and grassland.[16] At Taï, chimps can be found in the last remaining tropical rainforest in Côte d'Ivoire.[17] Chimps have advanced cognitive maps of their home ranges which they use to repeatedly locate food resources. A noisy group of animals, like birds or other primates, may direct a chimp to a new food source. They also may be lead to a new fruit tree or termite mound by a foraging partner that has been there previously.[15] The chimpanzee makes a night nest in a tree in a new location every night, with every chimpanzee in a separate nest other than infants or small chimpanzees, who sleep with their mothers.[18] When confronted by a predator, chimpanzees will react with loud screams and use any object they can against the threat. Leopard predation is apparently a significant cause of mortality in chimpanzees at Taï and Lopé National Park.[17][19] In some cases, chimpanzees have been documented killing leopard cubs,[20] an act which primarily seems to be a protective effort. Lions may have also preyed on chimps at Mahale Mountains National Park, where at least four chimpanzees could have fallen prey to lions.[21] Isolated cases of cannibalism have also been documented.

Food and foraging

Most of the chimpanzee’s diet is made up of fruit. Chimps prefer fruit above all other food items and will even eat them when they are not abundant. They will also eat leaves and leaf buds. Seeds, blossoms, stems, pith, bark and resin make up the rest of their diet.[15] While chimps are mostly herbivorous, they do eat honey, soil, insects, birds and their eggs and small to medium-sized mammals, including other primates.[22][15] The western red colobus ranks at the top of preferred mammal prey. Other mammalian prey include, red-tailed monkeys, yellow baboons, blue duikers, bushbucks and warthogs.[23] Jane Goodall documented many occasions within Gombe Stream National Park of chimpanzees and western red colobus monkeys ignoring each other within close proximity.[24][25]

Nearly all chimpanzee populations have been recorded using tools. They will modify sticks, rocks, grass, and leaves and use them for acquiring honey, termites, ants, nuts, and water. Despite the lack of complexity, there does seem to be forethought and skill in making these tools and should be considered such.[26] While it has been known since Jane Goodall's 1960s discovery that modern chimpanzees use tools, research published in 2007 indicates that chimpanzee stone tool use dates to at least 4,300 years ago.[27] A common chimpanzee from the Kasakela chimpanzee community was the first non-human animal observed making a tool, by modifying a twig to use as an instrument for extracting termites from their mound.[28][29][30] At Taï, chimps simply use their hands to extract termites.[26] When foraging for honey, chimps will use short sticks, strip them of their leaves, twigs, and bark and scoop the honey out of the hive, that is if the bees are stingless. For hives of the dangerous African honeybees, chimps use longer and thinner sticks to extract the honey.[31] Chimps will also use striped, long, thin sticks to extract ants from ground nests.[26] [15] Ant dipping is difficult and some chimps never master it. West African chimps will use fallen branches or hand-held stones and exposed tree roots or rocky outcroppings as hammers or anvils to crack open hard nuts.[26][17] Chimps that do this seem to exhibit forethought as these items are not found together or near a source of nuts. Nut cracking is also difficult and must be learned.[17] Chimps will also use leaves as sponges or spoons to drink water. They crumble the leaves in their mouths and submerge when in water where they act like sponges and the chimps will suck on them.[32]

A recent study revealed the use of such advanced tools as spears, which West African chimpanzees in Senegal sharpen with their teeth, being used to spear Senegal Bushbabies out of small holes in trees.[33] An eastern chimpanzee has been observed using a modified branch as a tool to capture a squirrel.[34]

When hunting small monkeys like the red colobus, chimps hunt in areas where the forest canopy is interrupted or irregular.[35] This allows them to easily corner the monkeys when chasing them in the appropriate direction. Chimps may also hunt as a coordinated team so that they can corner their prey even in a continuous canopy.[35] During an arboreal hunt, each chimp in the hunting groups has a role. "Drivers" serve to keep the prey running in a certain direction and follow them without attempting to make a catch. "Blockers" are stationed at the bottom of the trees and will climb up to block prey that take off an a different direction. "Chasers" move quickly and try to make a catch. Finally, "ambushers" hide and position themselves where no prey had reached yet and rush out when a monkey nears.[35] Both adult and infants are taken. However, adult male black-and-white colobus monkeys will attack the hunting chimps. In Gombe, chimps also fear adult colobus monkeys.[15] They prefer to snatch infants from their mother’s bellies without harming the mothers. Male chimps hunt more than females. When caught and killed, the meal is distributed to all hunting party members and even bystanders.[35]

Social behavior

Group structure

Common chimpanzees live in communities that typically range from 20 to more than 150 members, but spend most of their time travelling in small, temporary groups consisting of a few individuals, "which may consist of any combination of age and sex classes."[18] Both males and females will sometimes travel alone.[18] The common chimpanzee lives in a fission-fusion society and may be found in groups of the following types: all-male, adult females and offspring, consisting of both sexes, or one female and her offspring. Chimpanzees have complex social relationships and spend a large amount of time grooming each other.[36] At the core of social structures are males, who roam around, protect group members, and search for food. Males remain in their natal communities while females generally emigrate at adolescence. As such, males in a community are more likely to be related to one another than females are to each other. Among males, there is generally a dominance hierarchy and males are dominant over females.[37] However, this unusual fission-fusion social structure, "in which portions of the parent group may on a regular basis separate from and then rejoin the rest,"[15] is highly variable in terms of which particular individual chimpanzees congregate at a given time. This is mainly due to chimpanzees having a high level of individual autonomy within their fission-fusion social groups. Also, communities have large ranges that overlap with those of other groups.

As a result, individual chimpanzees often forage for food alone, or in smaller groups (as opposed to the much larger "parent" group, which encompasses all the chimpanzees who regularly come into contact and congregate into parties in a particular area). As stated, these smaller groups also emerge in a variety of types, for a variety of purposes. For example, an all-male troop may be organized in order to hunt for meat, while a group consisting of lactating females serves to act as a "nursery group" for the young.[38] An individual may encounter certain individuals quite frequently, but have run-ins with others almost never or only in large-scale gatherings. Due to the varying frequency at which chimpanzees associate, the structure of their societies is highly complicated.

Male chimpanzees exist in a linear dominance hierarchy. Top ranking males tend to be aggressive even during dominance stability.[39] This is likely due to the chimp’s fission-fusion society, with male chimps leaving groups and returning after extended periods of time. With this, a dominant male is unsure is if there has been any "political maneuvering" and must re-establish his dominance. Thus a large amount of aggression occurs 5-15 minutes after reunions.[39][40] During aggressive encounters, displays are preferred over attacks. [39][40] Males maintain and improve their social rank by forming coalitions. These coalitions have been characterized as "exploitive" and are based on an individual’s influence in agonistic interactions.[41] Being in a coalition allows males to dominate a third individual when they could not by themselves, as politically apt chimps can exert power over aggressive interactions regardless of their rank. Coalitions can also give an individual male the confidence to challenge a dominant male. The more allies a male has, the better his chance of becoming dominant. However most changes in hierarchical rank are caused by dyadic interactions.[39] Chimpanzee alliances can be very fickle and one member may turn on another if it serves him.[42] Low ranking males commonly switch sides in disputes between more dominant individuals. Low ranking males benefit from an unstable hierarchy and have increased sexual opportunities.[41][42] In addition, conflicts between dominant males causes them to focus on each other rather than the lower ranking males. Social hierarchies among adult females tend to be weaker. Nevertheless, the status of an adult female may be important for her offspring.[43] Females in Tai have also been recorded to form alliances.[44] Social grooming appears to be important in the formation and maintenance of coalitions.[45] It is more common among adult males than adult females.

Chimpanzees have been described as highly territorial and are known to kill other chimps,[46] although Margaret Power wrote in her 1991 book The Egalitarians that the field studies from which the aggressive data came, Gombe and Mahale, use artificial feeding systems that increased aggression in the chimpanzee populations studied and therefore might not reflect innate characteristics of the species as a whole.[9] In the years following her artificial feeding conditions at Gombe, Jane Goodall described groups of male chimps patrolling the borders of their territory brutally attacking chimps who had split off from the Gombe group. A study published in 2010 found that chimpanzees conduct wars over land, not mates.[47] Patrol parties from smaller groups are more likely to avoid contact with their neighbors. Patrol parties from large groups will even take over a smaller group's territory, gaining access to more resources, food and females.[15][42]

Mating and parenting

Chimpanzees mate year round and there is no evidence for a birth season. However, the number of females that are in estrus varies seasonally in a group.[17][48] Female chimps are more likely to come into estrus when food is readily available. Estrous females exhibit sexual swellings. Chimp mating tends to be promiscuous, with females mating with multiple males in her community during estrus, mostly during the 10-day period of maximal tumescence.[15] As such, males have large testicles for sperm competition. However, other forms of mating also exist. Dominant males sometimes restrict access to females in the community. There are also consortships, where a male and female leave their community for several days to weeks to mate and extra-pair matings where females leave their communities and mate with males from neighboring communities.[15][49] When committing to a specific community, females have limited choice in mates and the dominance hierarchy of males often dictates which males an estrous female will mate with. Thus alternative mating strategies give females more mating opportunities without losing the support of the males in their community.[49] Infanticide has been recorded in chimp communities in Gombe, Mahale, and Kibale National Parks. Male chimps practice infanticide on unrelated young to shorten the interbirth intervals in the females. There are also accounts of infanticide by females. There are questions whether cases of female infanticide are related to the dominance hierarchy in females or are simply isolated pathological behaviors.[15][43]

Care for the young is provided mostly by their mothers. The survival and emotional health of the young is dependent on maternal care.[15] Mothers provide their young with food, warmth, protection and teach them certain skills. In addition, a chimp’s future rank may be dependent on their mother’s status.[15][17] For their first 30 days, infants are in constant physical contact with their mothers, clinging to their bellies. Newborn chimps are helpless and have a grasping reflex that is not strong enough to support them for more than a few seconds. Infants are unable to support their own weight for their first two months and need their mothers' support.[50] When they reach 5-6 months, infants ride on their mothers’ backs. They remain in continual contact for the rest of their first year. When they reach two years of age, they begin to move and sit independently within five meters of their mothers.[50] By three years, infants will move more than five meters away from their mothers. By 4-6 years, chimps are weaned and infancy ends.[50] The juvenile period for chimps lasts from their sixth to ninth year. Juveniles remain close to their mothers but they also have more interactions with other members of their community. Adolescent females move between groups and are supported by their mothers in agonistic encounters. Adolescent males spend time with adult males in social activities like hunting and boundary patroling.[50]

Communication

Chimpanzees use a variety of facial expressions, postures and sounds to communicate with each other.[15] Chimps have expressive faces which are important in close-up communications. When in a frightening situation, a chimp will display a "full closed grin" which evokes an instant fear response in others. Other facial expression include the "lip flip," "pout," "sneer," and "compressed-lips face."[15] To show submission, a chimp will crunch, bob and extend a hand. To show aggression, a chimp will make itself appear larger by swaggering bipedally, hunching over and waving the arms.[15] In certain contexts, such as traveling, finding large food sources, displaying and encounter another community, chimps will beat their hands and feet against the trunks of large tree, an act known as "drumming."[51]

Vocalizations are also important in chimp communication. The most common and important call in adults is the "pant-hoot." These calls are meant to display excitement, sociability feelings and enjoyment of food.[15] Pant-hoots are made of four parts, starting with soft "hoos" that increase in volume and build up to the climax of that call which is made up of screams and sometimes barks and the scream die down to soft "hoos" again as the call ends.[51] Submissive individuals will direct "pant-grunts" towards their superiors.[15][43] Chimps use distance calls to draw attention to danger, food sources or other community members.[15] "Barks" may be modified to "short barks" when hunting and "tonal barks" when sighting large snakes.[51]

Interaction with humans

Attacks

Common chimpanzees have been known to attack humans on occasion.[52][53] There have been many attacks in Uganda by chimpanzees against human children; the results are sometimes fatal for the children. Some of these attacks are presumed to be due to chimpanzees being intoxicated (from alcohol obtained from rural brewing operations) and mistaking human children[54] for the Western Red Colobus, one of their favourite meals.[55] The dangers of careless human interactions with chimpanzees are only aggravated by the fact that many chimpanzees perceive humans as potential rivals.[56] With up to 5 times the upper body strength of a human, an angered chimpanzee could easily overpower and potentially kill even a fully grown man, as shown by the attack on and near death of former NASCAR driver St. James Davis.[57][58] Another example of chimpanzee to human aggression occurred February 2009 in Stamford, Connecticut, when a 200-pound (91 kg), 14-year-old pet chimp named Travis attacked his owner's friend, who lost her hands, eyelids, nose and part of her upper jaw/sinus area from the attack.[59][60] There are at least 6 documented cases of chimpanzees snatching and eating human babies.[61]

Link with Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1

Two types of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infect humans: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the more virulent and easily transmitted, and is the source of the majority of HIV infections throughout the world; HIV-2 is largely confined to west Africa.[62] Both types originated in west and central Africa, jumping from primates to humans. HIV-1 has evolved from a Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIVcpz) found in the common chimpanzee subspecies, Pan troglodytes troglodytes, native to southern Cameroon.[63][64] Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, has the greatest genetic diversity of HIV-1 so far discovered, suggesting that the virus has been there longer than anywhere else. HIV-2 crossed species from a different strain of SIV, found in the Sooty Mangabey, monkeys in Guinea-Bissau.[62]

Status and conservation

Most countries in which chimpanzees live have laws protecting them and have numerous national parks that contain them, although many chimps live outside the protected areas.[2]

The biggest threats to the common chimpanzee are habitat destruction, poaching and disease.[2] Chimpanzee habitats have been severely reduced by deforestation across West and Central Africa. More than 80% of the region’s original forest cover have been lost.[2] Road building has caused habitat degradation and fragmentation of chimpanzee popualtion and may possibly increase poaching in areas that have not been seriously impacted by such anthropogeniic pressures previously.[2] Deforestation rates are low in western Central Africa but selective logging may be done in most of the forests outside national parks.[2]

Chimpanzee are a common target for poachers. In Côte d’Ivoire, chimpanzees make up 1-3% of bushmeat sold in urban markets.[2] They are also taken in pet trades. Although all range countries that are signatories to CITES have made the pet trade illegally, it continues across Africa illegally.[2] Chimpanzees are also hunted for medicinal purposes in some localities.[2] Capturing chimpanzees for scientific research is still officially permitted in some range countries, such as Guinea.[2] People will intentionally kill chimpanzees to protect their crops.[2] Chimps may also be unintentionally maimed or killed by snares meant for other animals.

Infectious diseases are a main cause of death for chimpanzees. Chimpanzees succumb to many diseases that afflict humans since the two species are so similar.[2] As human populations expand, the frequency of encounters between chimpanzees and humans and/or human waste increases and this leads to higher risks of disease transmission between humans and chimpanzees.[2]

See also

- Chimp Haven

- Great ape personhood

- Homininae

- Johann Friedrich Blumenbach Blumenbach and the Chimpanzee

- List of apes - list of notable individuals

- Theory of mind

- The Third Chimpanzee

- Bili Ape

References

- ^ Groves, C. (2005). Wilson, D. E., & Reeder, D. M, eds. ed. Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 183. OCLC 62265494. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=12100797.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Oates, J.F., Tutin, C.E.G., Humle, T., Wilson, M.L., Baillie, J.E.M., Balmforth, Z., Blom, A., Boesch, C., Cox, D., Davenport, T., Dunn, A., Dupain, J., Duvall, C., Ellis, C.M., Farmer, K.H., Gatti, S., Greengrass, E., Hart, J., Herbinger, I., Hicks, C., Hunt, K.D., Kamenya, S., Maisels, F., Mitani, J.C., Moore, J., Morgan, B.J., Morgan, D.B., Nakamura, M., Nixon, S., Plumptre, A.J., Reynolds, V., Stokes, E.J. & Walsh, P.D. (2008). Pan troglodytes. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 4 January 2009. Database entry includes justification for why this species is endangered

- ^ p. 37 in Blumenbach, J. F. 1776. De generis hvmani varietate nativa liber. Cvm figvris aeri incisis. - pp. [1], 1-100, [1], Tab. I-II [= 1-2]. Goettingae. (Vandenhoeck).

- ^ AnimalBase species taxon summary for troglodytes Blumenbach, 1776 described in Simia, version 11 June 2011

- ^ Kroke, C. 2010. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Bibliographie seiner Schriften. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag, No. 1 and 2.

- ^ ICZN Code Art. 8.1.1

- ^ Online Etymology Dictionary: Chimpanzee

- ^ Cohen, Joel E. (Winter 1993). "Going Bananas". American Scholar.

- ^ a b Margaret Power (December 1993). "Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees". American Anthropologist 95 (4): 1010–11.

- ^ Won YJ, Hey J (February 2005). "Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees". Mol. Biol. Evol. 22 (2): 297–307. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi017. PMID 15483319. http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/content/22/2/297.full.pdf+html.

- ^ Fischer A, Wiebe V, Pääbo S, Przeworski M (May 2004). "Evidence for a complex demographic history of chimpanzees". Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 (5): 799–808. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh083. PMID 14963091.

- ^ Goldman D, Giri PR, O'Brien SJ (May 1987). "A molecular phylogeny of the hominoid primates as indicated by two-dimensional protein electrophoresis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84 (10): 3307–11. Bibcode 1987PNAS...84.3307G. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.10.3307. PMC 304858. PMID 3106965. http://www.pnas.org/content/84/10/3307.full.pdf+html.

- ^ Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (September 2005). "Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome". Nature 437 (7055): 69–87. Bibcode 2005Natur.437...69.. doi:10.1038/nature04072. PMID 16136131. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v437/n7055/full/nature04072.html.

Cheng Z, Ventura M, She X, et al. (September 2005). "A genome-wide comparison of recent chimpanzee and human segmental duplications". Nature 437 (7055): 88–93. Bibcode 2005Natur.437...88C. doi:10.1038/nature04000. PMID 16136132. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v437/n7055/full/nature04000.html. - ^ Poulsen JR, Clark CJ (2004). "Densities, distributions, and seasonal movements of gorillas and chimpanzees in swamp forest in northern Congo". Int J Prim 25 (2): 285–306. doi:10.1023/B:IJOP.0000019153.50161.58.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Goodall, Jane (1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. ISBN 0674116496.

- ^ Sugiyama Y, Koman J (1987). "A preliminary list of chimpanzees' alimentation at Bossou, Guinea". Primates 28 (1): 133–47. doi:10.1007/BF02382192.

- ^ a b c d e f Boesch C, Boesch-Achermann H. (2000) The chimpanzees of the Taï Forest: behavioral ecology and evolution. Oxford, England: Oxford Univ Pr.

- ^ a b c Van Lawick-Goodall, Jane (1968). "The Behaviour of Free-Living Chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs (Rutgers University) 1 (3): 167.

- ^ Henschel P, Abernethy KA, White LJT (2005). "Leopard food habits in the Lopé National Park, Gabon, Central Africa". Afr J Ecol 43 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2004.00518.x.

- ^ "Aggression toward Large Carnivores by Wild Chimpanzees of Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania". Content.karger.com. 2008-09-11. http://content.karger.com/ProdukteDB/produkte.asp?Aktion=ShowPDF&ArtikelNr=000156259&Ausgabe=238792&ProduktNr=223842&filename=000156259.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ^ Tsukahara T (10 September 1992). "Lions eat chimpanzees: The first evidence of predation by lions on wild chimpanzees". American Journal of Primatology 29 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350290102.

- ^ Isabirye-Basuta G. (1989) "Feeding ecology of chimpanzees in the Kibale Forest, Uganda". In: Heltne PG, Marquardt LA, editors. Understanding chimpanzees. Cambridge, (MS): Harvard Univ Pr; p 116-27.

- ^ Boesch C, Uehara S, Ihobe H. (2002) "Variations in chimpanzee-red colobus interactions". In: Boesch C, Hohmann G, Marchant LF, editors. Behavioral diversity in chimpanzees and bonobos. Cambridge, England: Cambridge Univ Pr; p 221-30.

- ^ "Chimps on the hunt". BBC Wildlife Finder. 1990-10-24. http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/species/Common_Chimpanzee#p004hd8g. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ^ Van Lawick-Goodall, Jane (1968). "The Behaviour of Free-Living Chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs (Rutgers University) 1 (3): 191.

- ^ a b c d Boesch C, Boesch H. (1993) "Diversity of tool use and tool-making in wild chimpanzees". In: Berthelet A, Chavaillon J, editors. The use of tools by human and non-human primates. Oxford, England: Oxford Univ Pr; p 158-87.

- ^ Mercader J, Barton H, Gillespie J, et al. (February 2007). "4,300-year-old chimpanzee sites and the origins of percussive stone technology". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (9): 3043–8. Bibcode 2007PNAS..104.3043M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607909104. PMC 1805589. PMID 17360606. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/104/9/3043.

- ^ Goodall, J. (1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 535–539. ISBN 0-674-11649-6.

- ^ Goodall, J. (1971). In the Shadow of Man. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 35–37. ISBN 0-395-33145-5.

- ^ "Gombe Timeline". Jane Goodall Institute. Archived from the original on 2008-01-25. http://web.archive.org/web/20080125194313/http://www.janegoodall.org/jane/study-corner/chimpanzees/gombe-timeline.asp. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ^ Stanford CB, Gamaneza C, Nkurunungui JB, Goldsmith ML (2000). "Chimpanzees in Bwindi-Impenetrable National Park, Uganda, use different tools to obtain different types of honey". Primates 41 (3): 337–41. doi:10.1007/BF02557602.

- ^ Sugiyama Y (1995). "Drinking tools of wild chimpanzees at Bossou". Am J Prim 37 (1): 263–9. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350370308.

- ^ Fox, M. (2007-02-22). "Hunting chimps may change view of human evolution". Archived from the original on 2007-02-24. http://web.archive.org/web/20070224115149/http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20070222/sc_nm/chimps_hunting_dc. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ Huffman MA, Kalunde MS (January 1993). "Tool-assisted predation on a squirrel by a female chimpanzee in the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania" (PDF). Primates 34 (1): 93–8. doi:10.1007/BF02381285. http://www.springerlink.com/content/u1g710357w253541/fulltext.pdf.

- ^ a b c d Leipzig G (2002). "COOPERATIVE HUNTING ROLES AMONG TAI CHIMPANZEES". Human Nature 13 (1): 27–46. doi:10.1007/s12110-002-1013-6.

- ^ The Chimpanzees of Tanzania". Wild Kingdom. December 31, 1976.

- ^ Goldberg TL, Wrangham RW (1997). "Genetic correlates of social behavior in wild chimpanzees: evidence from mitochondrial DNA". Anim Beh 54 (3): 559–70. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0450.

- ^ Pepper JW, Mitani JC, Watts DP (1999). "General gregariousness and specific social preferences among wild chimpanzees". Int J Prim 20 (5): 613–32. doi:10.1023/A:1020760616641.

- ^ a b c d Muller, MN. (2002) "Agonistic relations among Kanyawara chimpanzees". In: Boesch C, Hohmann G, Marchant LF, editors. Behavioural diversity in chimpanzees and bonobos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p 112-124.

- ^ a b Bygott, JD. (1979) "Agonistic behavior, dominance, and social structure in wild chimpanzees of the Gombe National Park". In: Hamburg, DA, McCown, ER, editors. The great apes. Menlo Park: Benjamin-Cummings. P 73-121.

- ^ a b de Waal, FBM. (1987) "Dynamic of social relationships". In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT, editors. Primate societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 421-429.

- ^ a b c Nishida, T., M. Hiraiwa-Hasegawa. (1986) "Chimpanzees and Bonobos: Cooperative Relationships among Males". Pp. 165-177 in B.B. Smuts, D.L. Cheyney, R.M. Seyfarth, R.W. Wrangham, T.T. Struhsaker, eds. Primate Societies. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

- ^ a b c Pusey AE, Williams J, Goodall J (1997). "The influence of dominance rank on the reproductive success of female chimpanzees". Science 277 (5327): 828–831. doi:10.1126/science.277.5327.828. PMID 9242614.

- ^ Stumpf, R. (2007) "Chimpanzees and bonobos: Diversity within and between species". In: Campbell CJ, Fuentes A, Mackinnon KC, Pancer M, Bearder SK, editors. Primates in perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. p 321-344.

- ^ Watts DP (2001). "Reciprocity and interchange in the social relationships of wild male chimpanzees". Behaviour 139: 343–370.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (2009-02-18). "Why the Stamford Chimp Attacked". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1880229,00.html. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ "Killer Instincts". The Economist. 2010-06-24. http://www.economist.com/node/16422404.

- ^ Wallis J. (2002) "Seasonal aspects of reproduction and sexual behavior in two chimpanzee populations: a comparison of Gombe (Tanzania) and Budongo (Uganda) ". In: Boesch C, Hohmann G, Marchant LF, editors. Behavioural diversity in chimpanzees and bonobos. Cambridge (England): Cambridge Univ Pr. p 181-91.

- ^ a b Gagneux P, Boesch C, Woodruff DS (1999). "Female reproductive strategies, paternity and community structure in wild West African chimpanzees". Anim Beh 57: 19–32. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0972.

- ^ a b c d Bard KA. (1995) "Parenting in primates". In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting. Volume 2, Biology and ecology of parenting. Mahwah (NJ): L Erlbaum Associates; p 27-58.

- ^ a b c Crockford C, Boesch C (2005). "Call combinations in wild chimpanzees". Behaviour 142 (4): 397–421. doi:10.1163/1568539054012047.

- ^ Claire Osborn (2006-04-27). "Texas man saves friend during fatal chimp attack". The Pulse Journal. http://www.pulsejournal.com/featr/content/shared/news/stories/CHIMP_ATTACK_0427_COX.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.[dead link]

- ^ "Chimp attack kills cabbie and injures tourists". London: The Guardian. 2006-04-25. http://www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,,1760554,00.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ "'Drunk and Disorderly' Chimps Attacking Ugandan Children". 2004-02-09. http://www.primates.com/chimps/drunk-n-disorderly.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ Tara Waterman (1999). "Ebola Cote D'Ivoire Outbreaks". Stanford University. http://virus.stanford.edu/filo/eboci.html. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ^ "Chimp attack doesn’t surprise experts". MSNBC. 2005-03-05. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/7087194/. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ "Birthday party turns bloody when chimps attack". USATODAY. 2005-03-04. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-03-04-chimp-attack_x.htm. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ Amy Argetsinger (2005-05-24). "The Animal Within". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/05/23/AR2005052301819.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ^ Sandoval, Edgar (2009-02-18). "911 tape captures chimpanzee owner's horror as 200-pound ape mauls friend". New York: Nydailynews.com. http://www.nydailynews.com/news/2009/02/17/2009-02-17_911_tape_captures_chimpanzee_owners_horr-2.html/. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ By Stephanie Gallman CNN (2009-02-18). "Chimp attack 911 call: 'He's ripping her apart' - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. http://edition.cnn.com/2009/US/02/17/chimpanzee.attack/. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ "Online Extra: Frodo @ National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. 2002-05-15. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0304/feature4/online_extra2.html. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ^ a b Reeves JD, Doms RW (June 2002). "Human immunodeficiency virus type 2". J. Gen. Virol. 83 (Pt 6): 1253–65. doi:10.1099/vir.0.18253-0. PMID 12029140. http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12029140.

- ^ Keele BF, Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, et al. (July 2006). "Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1". Science 313 (5786): 523–6. Bibcode 2006Sci...313..523K. doi:10.1126/science.1126531. PMC 2442710. PMID 16728595. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2442710.

- ^ Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson DL, et al. (February 1999). "Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes". Nature 397 (6718): 436–41. Bibcode 1999Natur.397..436G. doi:10.1038/17130. PMID 9989410.

- General references

- Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa, 1775.

- Tutin CEG, McGrew WC, Baldwin PJ (1983). "Social organization of savanna-dwelling chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, at Mt. Assirik, Senegal". Primates 24 (2): 154–173. doi:10.1007/BF02381079.

External links

- DiscoverChimpanzees.org

- Chimpanzee Genome resources

- Primate Info Net Pan troglodytes Factsheets

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Species Profile

- New Scientist 19 May 2003 - Chimps are human, gene study implies

- Video clips and news from the BBC (BBC Wildlife Finder)

Extant species of family Hominidae (Great apes) Ponginae Homininae CategoryApe-related articles Ape species

Ape study Ape language · Ape Trust · Dian Fossey · Birutė Galdikas · Jane Goodall · Chimpanzee genome project · Human genome project · Neanderthal genome project · Willie Smits · Lone Drøscher Nielsen · Borneo Orangutan SurvivalLegal and social status See also Bushmeat · Ape extinction · List of notable apes · List of fictional apes · Human evolution · Mythic humanoids · HominidCategories:- IUCN Red List endangered species

- Animals described in 1776

- Chimpanzees

- Fauna of West Africa

- Mammals of Africa

- Mammals of Angola

- Mammals of Burkina Faso

- Mammals of Burundi

- Mammals of Cameroon

- Mammals of the Central African Republic

- Mammals of the Republic of the Congo

- Mammals of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Mammals of Côte d'Ivoire

- Mammals of Equatorial Guinea

- Mammals of Gabon

- Mammals of Ghana

- Mammals of Guinea

- Mammals of Guinea-Bissau

- Mammals of Liberia

- Mammals of Mali

- Mammals of Nigeria

- Mammals of Senegal

- Mammals of Sierra Leone

- Mammals of Sudan

- Mammals of Tanzania

- Mammals of Uganda

- Megafauna of Africa

- Sequenced genomes

- Tool-using species

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.