- Church Army Chapel, Blackheath

-

Church Army Chapel, Blackheath

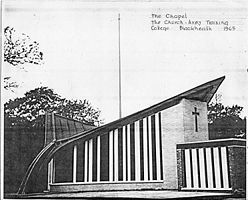

Drawing by E.T. SpashettGeneral information Architectural style Modern Town or city Greenwich, Greater London Country United Kingdom Construction started 1964 Completed 1965 Cost £250,000 (whole site)[1] Technical details Structural system Saddle roof and sectional aluminium spire Design and construction Client Church Army Architect Ernest Trevor Spashett ARIBA

(1923-94)Structural engineer Woodgate (Blackheath) Ltd, Montpelier-vale, Blackheath[2] The Church Army Chapel at Vanbrugh Park, Blackheath, Greater London, designed by Ernest Trevor Spashett (1923-1994), opened in 1965 by Princess Alexandra and consecrated by Michael Ramsey, is a locally listed building of outstanding architectural significance, and is notable for originally having had the tallest sectional aluminium spire of its time, and for being one of the earliest 20th century chapels of modern design to have been conceived with a central altar. It is now part of Blackheath High School.

Contents

Local listing description

At Greenwich Council building conservation department[3] it is locally listed as a building of outstanding architectural significance, under the name of the Wilson Carlile Training College Chapel at 27 Vanbrugh Park, Blackheath, London, by architect E.T. Spashett. It is described as: "An interesting modern building of unusual design featuring a striking gull wing upper roof swept to ground level on one side; grey brick with tall, narrow window lights".[4][5] Local listings have no reference number. By the time Greenwich Council planning department assessed it in the 1980s, the spire was down and lying alongside the building. The building could not be upgraded to national status by The Department for Culture, Media and Sport, representing English Heritage[6] in April 1999, as the spire was gone so the massiveness of the roof structure could no longer be understood by the assessors who were puzzled to find it "overscaled".[7] When opened complete with spire in 1965, the South East London Mercury described the chapel as "a showpiece of modern architecture and building technique".[2]

Design

1964 model of site showing spire fixed to centre of roof

1964 model of site showing spire fixed to centre of roof

See images here and here and here. The Church Army[8] does not normally have a chapel as it does outreach work, but in the 1960s an exception was made for its headquarters at Blackheath, possibly as the chapel could be considered part of the training college.[9]

Spire

The concept for the building is embodied in the spire, which was a very tall, slim, hollow aluminium cone at least twice the height of the building again, chosen for its lightness and strength as proved in the aeroplane construction industry - the architect being ex-Royal Air Force[10] - and built in Bristol by British Aerospace.[11] It was made up of a series of overlapping hollow sections decreasing in size up to the final cone-section at the top, like a Victorian hand-held brass telescope, but with the overlaps of the expanding sections reversed.[12] A small cross-piece through the top cone section doubled as the hilt of a sword, representing the Church Army in the context of such Biblical expressions as "good soldier of Christ".[13] The cross-shaped top was also reminiscent of the capping-crosses of medieval spires like the one on Salisbury Cathedral (see image, below). A slightly similar type of aluminium spire had been added to the top of the Chrysler Building in 1929, allegedly as a surprise in that it created, temporarily, New York's tallest building.[14] St. Michael's Parish Church, Linlithgow has a controversial "crown of thorns" aluminium spire of sectional construction, erected in 1964.[15] However, if one compares the spires alone, this spire was taller than those. It is said to have towered above adjacent buildings discreetly due to its thinness, and could be seen from the Heath.[11]

Loss of the spire

Salisbury Cathedral showing cross capping medieval spire

Salisbury Cathedral showing cross capping medieval spire

Like all ground-breaking designs it required development. Being sectional, it was designed to move to absorb stresses, and being aluminium, it was light. When it was first taken down after stresses were revealed in piles (not the roof) in summer 1965, unusually thick cushioning had to be added to the bases of the piles in the undercroft.[16] A larger aluminium base and fixing point was manufactured for the spire. The second installation of the spire was its final test, the result of which would provide the information needed to design the final and permanent fixing. However when the spire was taken down for the second time, there was no architect or plans available, and the spire lay for some years in pieces on the ground alongside the building. It was never replaced, because only the architect knew how to replace it permanently.He did not refuse to do so, but having left the company after being locked out of the consecration service, Spashett had taken the plans with him, and made himself available to the Church Army to oversee the reinstatement of the spire. However the Church Army's contract with Austin Vernon provided for free backup architectural service, so they declined Spashett's offer, and the spire was never reinstated because remaining staff at the company had not been involved in the design, and did not have the plans. In 1989 Spashett left the plans in Tunbridge Wells for safekeeping,[17] and never retrieved them.[11][18] The present whereabouts of the plans is unknown,[19] and the spire was gone and forgotten by the time Blackheath High School bought the building in 1994.

The spire had a flanged base, mounted on a round plate, then a rectangular plate. The shape of this plate, which was enlarged during development, was still visible on Google Earth in its 2006 photographs of the chapel roof, and can be seen in the 1960s and 2009 photographs of the roof below.

Building

In the official programme for the 1965 opening[20] the building is described as follows:

"The chapel is of special interest: it has been planned to suit modern conceptions of worship, with the faithful gathered round the communion table and the celebrant normally facing the people. Its shell roof is in the shape of a hyperbolic paraboloid, and is constructed of three thin skins of timber laid in different directions, glued and spiked, being supported entirely by its two buttresses. The slit windows which run from floor to roof are separated by concrete pillars faced outside with a white mosaic tile finish and inside with white leather-cloth. The furnishings and doors are of American black walnut and the floor is a grey-green terrazzo."[21]

The columns between the windows do not appear to meet the roof when viewed from below: this gives a floating-roof effect. Although the tops of the white brick walls on the east and west elevations are fixed to the roof to stabilise it, the floating-roof effect is continued with a top row of dark blue engineering bricks with dark pointing. Viewed from below, this row can look like a gap between wall and roof. This row is clearly shown in a photograph in the Blackheath Reporter.[22][23]

Roof

The chapel has a saddle roof: mathematically, this is a hyperbolic paraboloid, which, as a doubly ruled surface, can be constructed from two rows of straight beams.

The chapel has a saddle roof: mathematically, this is a hyperbolic paraboloid, which, as a doubly ruled surface, can be constructed from two rows of straight beams.

One inspiration for the building was Le Corbusier and his Modular Man[24] proportions and saddle roofs.[25] By 1963 when the building was at the design stage it was known that the prefabricated shell-roof version, constructed of thin, cast, reinforced concrete, was subject to being lifted bodily from buildings by high winds and that some shapes such as this one could create a drainage problem.[26] Drainage could compromise the smooth appearance with guttering and pipes, or it could encourage chronic leakage over time if holes had to be made in the structure. But by this time wood was a viable alternative for a hyperbolic paraboloid,[27] and with this roof the drainage is part of the aesthetics where it runs down the front and back, so that the roof forms its own flying buttresses, supports its own weight, drains itself, anchors itself to the ground and allows the roof to form part of the building frame.[11] The metal-covered timber roof suffered damage from thieves in 2008, and it was re-covered using a new system.[28][29][30]

The roof is a saddle roof, meaning that it is in the shape of a hyperbolic paraboloid, and thus the curved shape can be constructed with straight beams; a previous example was a 1956 Kansas house.[27]

Interior

Inspiration from Pettie's Vigil

The Vigil, 1884, by John Pettie

The Vigil, 1884, by John Pettie

The cross-shaped blue glass window on the east side[31] was intended to double as a symbolic sword-shape, like the original spire. This is because the first inspiration for the building was The Vigil by John Pettie, 1884.[32] In the painting, a squire holds his vigil by praying overnight before his knighting ceremony, hoping that he and his equipment might be purified beforehand.[33] As the design of the spire was inspired by the vertical position of the squire's sword, which symbolises the cross, so the natural lighting inside the chapel is inspired by this painting. In The Vigil, the dawn light falls from the east window above the altar onto the squire and his sword, and the purification is symbolised by the glow of the white surplice. A shadow below the squire's arm crosses a crease in the surplice, giving the effect of a shadowy cross on his torso.[34][35] In the Blackheath chapel, a blue celestial light is designed to fall in the shape of a cross or sword across the central altar of the basilica-shaped[36] interior from the east side, symbolically purifying the Church Army congregation before their day's work.[11]

The tall, rectangular windows of the building were inspired by the gallery of shadowy pillars in the background of the painting. There is a theory that medieval pillars and fan vaulting had some connection with the appearance of an avenue of trees.[37] In the Church Army chapel, the series of attenuated openings gives a gallery of daylight colours and views of the greenery of the Blackheath environment - so that the nave and aisles are now visually returning to the outdoors.[11]

Acoustics, air ducts and undercroft

Architectural acoustics for church music were seriously considered with regard to the chapel. There was some contemporary discussion of the study of acoustics that went into the building of the Queen Elizabeth Hall and Purcell Room in London with their alleged Helmholtz resonators and of Liverpool Cathedral - however some experimentation was done with sound-absorbent surfaces[11] such as the white leather-cloth mentioned in the May 1965 programme above. There are warm air ducts under the building, originally served by an oil fired central heating boiler in the north-west undercroft,[38] and warm-air grilles in the skirting inside the chapel, seen in the interior photograph below. The heavy roof, made of three layers of beams, a copper roof-covering and a wood-panelled lining, is a heat-insulator more powerful than some of the pre-cast hyperbolic paraboloid roofs being manufactured in the 1960s.[11]

The building stands on a hollow box, just over 6 ft high, known as the undercroft, and this is divided horizontally into several odd-shaped and unequal sections by brick walls which lend some rigidity to the structure, and give some support to the cast concrete horizontal joists which underlie the chapel floor and surrounding walkway. On the cast concrete joists is screed, and on that is the grey-green terrazzo interior flooring, and the exterior sandstone walkway. The main stresses from the weight of the building's frame, i.e. the roof, are carried by the two roof buttresses, but the piles below these cannot be seen from inside the undercroft. The east and west brick walls of the chapel were designed to prevent the two high corners of the roof from rocking due to stresses from the spire in a gale. The bases of these can be seen in the undercroft. There is no evidence that these end walls involve piles driven deep into the ground, but they were reinforced at the base during stabilisation of the spire at the development stage in summer 1965. The original air duct and fan are still there. When a box has a weight on top, its side walls want to splay outwards, so the outer walls of this box were originally supported by earth on all four sides. The north side is now exposed due to a new build. Apart from that, the chapel stands on a box of air.[11]

History

Opening

The foundation stone was laid in March 1964.[39] The chapel was part of the Church Army Wilson Carlile Training College designed by the same architect, and was opened by Princess Alexandra at 2.45pm on 6 May 1965,[40][41][1] the opening being commemorated on a marble stone in a cloakroom off the entrance lobby to the chapel. The late R.G.D. (Russell) Vernon MBE,[42] head of Austin Vernon & Partners under whose banner the chapel was designed, was invited to the opening at which the Archbishop of Canterbury Michael Ramsey was to consecrate the chapel. However Vernon knew nothing of the building, as its design had been delegated to E.T. Spashett RIBA. Spashett arrived in his best suit with his wife, his invitation and a camera, as this was his masterpiece and he had spent two years on the project. However he had not been invited to join the VIPs at the consecration inside the building, and was turned away when he tried to get in, although he remained on the fringes of the event, photographing the consecration procession as it circled the building.[11] As in medieval times, architecture is still produced within the studio system, in which the owner of the architectural firm is officially credited with all designs. A paragraph in the programme may have instigated the architect's action at the opening. It says:

"At 3.45 p.m. A procession will be formed to move from the marquee to the Chapel for the dedication of the College. The procession will consist of students and staff... the Architect and all who are seated on the platform."[20]

-

Pews and west-end altar in chapel, 1965[43]

Adaptations

The explanation of "modern conceptions of worship with the faithful gathered round the communion table" in the opening-day programme refers to the original design of a central altar as in Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral which was completed two years later. It was a response to the Liturgical Movement. Therefore it is possible that this was the first 20th century chapel of modern design to have been conceived with a central altar. However the Church Army unexpectedly installed pews and a west-end altar, as seen in the above photo.[43] The interior white leather-cloth for fine acoustic adjustment is now missing; removed by decorators. The terrazzo floor is covered with a sprung wooden floor (see photos above) which may also possibly serve to protect the original floor; however the terrazzo is still visible in the chapel lobby. According to photographs taken of the interior of the chapel in December 2009: since summer 2009 the corner windows by the buttresses have been replaced with mirror-glass; also the dance-barre has been removed on each side, making dancing pupils vulnerable to falling against the window glass, as evidenced by a boarded-up pane which was once original yellow glass.

Owners of the chapel and college

The first owner was the Church Army, who needed the buildings for their Wilson Carlile Training College in 1965.[40][44] The training college moved to Sheffield in 1991-92.[45] The premises were sold by the Church Army in 1994 to Blackheath High School, which between 1999 and 2009 was using the chapel as a music room and dance studio.[46]

Wilson Carlile Training College site 1965

The chapel was part of a larger build in 1965, and was designed to form part of the south side of an open, central quadrangle (see image of architectural model). The east side consisted of older buildings, and the west side was open, so the only other major new build was the large dormitory block on the north side. This was an international style building of white brick with metal-framed windows and black slate panels between the windows and covering the sills. Only two staircases and the upper part of the west end of this block remain in original condition, as there has been much development on the site since 1965. The description of the site in the May 1965 opening day programme is as follows:

"The new College has accommodation for seventy-two students and in addition three flats are provided nearby for married students and their families. Staff are accommodated either in the College or in adjoining houses, provision has been made for four lecture rooms, library, common rooms etc., and the grounds which cover two acres include spacious lawns and an asphalt area for tennis and netball."[20][47]

RIBA archives holdings

Five black and white photographs dated 1975 are held in the RIBA Archives as part of their Press Office collection and described as follows:[48]

- London: Church Army's Chapel, Blackheath: ext view showing double-curved roof (archts Austin Vernon & Partners, 1965) (BM/ECCL/40/A) (photo G. Hana Ltd 28978)

- London: Church Army's Chapel, Blackheath: ext view (archts Austin Vernon & Partners, 1965) (BM/ECCL/40/B) (photo G. Hana Ltd 28976)

- London: Church Army's Chapel, Blackheath: ext view showing double-curved roof (archts Austin Vernon & Partners, 1965) (BM/ECCL/40/C) (photo G. Hana Ltd 28977)

- London: Church Army's Chapel, Blackheath: int view (archts Austin Vernon & Partners, 1965) (BM/ECCL/40/D) (photo G. Hana Ltd 28975)

- London: Church Army's Chapel, Blackheath: int view (archts Austin Vernon & Partners, 1965) (BM/ECCL/40/E) (photo G. Hana Ltd 28974)

Architect: E. T. Spashett

Ernest Trevor Spashett (1923-1994) was born in Penzance and served in the Royal Air Force 1942-1947, flying Halifaxes.[49] He was apprenticed in Penzance, Cornwall before World War II, designing under supervision the Guildhall at St Ives in 1939 at the age of 16. After the war he trained as an architect with the Ministry of Works repairing London after the war, working on Alexandra Palace[50], Clarence House[51] and Osterley House among others.[52][11] For example, Osterley House was then an RAF convalescence home full of airmen in wheelchairs and on crutches. The zig-zag, half-fenced ramp he designed for the front steps instantly became a racetrack, and had to be heavily-fenced after too many skid turns on the corners created flying wheelchairs. He designed the replacement rose window for Alexandra Palace, the original being lost due to bomb damage.[53]

After qualifying as an architect he worked for Cambridge, Gillingham and Birmingham Councils designing council housing, schools and hospitals. He worked with Yates, Cook and Derbyshire in London from around 1954 to around 1960, then from around 1960 with Austin Vernon & Partners[54] (who had refurbished Dulwich Picture Gallery) in Dulwich from 1959, leaving after the chapel opening debacle in 1965. He specialised in church design and restoration, so in the 1960s and 1970s he was consultant architect for the Benedictines, taking instructions from Basil Hume. In the 1970s he designed accommodation at two monasteries, including a large, reflective, gold, cross-shaped window (now lost) at Gorton Monastery, Manchester, which at certain seasons caused a gold cross-shaped reflection on the public roadway.[55] From 1965 he was architect for estate agents Geering and Colyer in Tunbridge Wells,[56] then left to work freelance in Tunbridge Wells 1982-1989.[11] He continued freelance work in Herne Bay, Kent until retirement due to ill health in 1992. He died in 1994.

References

- ^ a b Unknown journalist (7 May 1965). "Charlton royal visit". Blackheath Reporter: 1.

- ^ a b Unknown journalist (14 May 1965). "The princess was late for tea: royal time-table "forgotten": Church Army College Opening". South East London Mercury: 7.

- ^ "Greenwich Council". Planning and Building department. http://www.greenwich.gov.uk/Greenwich/YourEnvironment/PlanningAndBuilding/. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "Buildings of Local Architectural or Historic Interest Borough of Greenwich". Vanbrugh Park, SE3 Wilson Carlisle Training College Chapel (Spashett's name incorrectly spelled as of November 2010, but Council has agreed to correct it). Greenwich Council. Compiled 1983; updated 2010. http://www.greenwich.gov.uk/NR/rdonlyres/3077F8FA-28C0-4AB2-8CD8-50FEC16CE417/0/LocalListofBuildingsJuly2010.pdf. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- ^ Information held by Greenwich Council Buildings Conservation Officer

- ^ "English Heritage". Public archive (National Monuments Record). http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/server/show/nav.19915. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Buildings, Monuments and Sites; Duncan Galbraith (12 April 1999). Letter: Planning (listed buildings and conservation areas)Act 1990; Buildings of special architectural or historic interest; Blackheath School for Girls, 27 Vanbrugh Park, Greenwich; Ref HSD/5012/274/SL1455-98.

- ^ "Church Army Online". Homepage. http://www.churcharmy.org.uk/pub/home.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-16.[dead link]

- ^ "Church Army Online". FAQs: General Questions:What is Church Army?. http://www.churcharmy.org.uk/faq.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-16.[dead link]

- ^ "Pilotfriend". Aviation, the first 100 years: Handley Page Halifax. The Ailerons on a Halifax are aluminium.. http://www.pilotfriend.com/photo_albums/timeline/ww2/Handley%20Page%20Halifax.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Information from architect's archives.

- ^ Such a telescope was the first inspiration for the construction of the spire: information from architect, 1964.

- ^ "Center for church music, songs and hymns". Onward Christian Soldiers. 2009. http://www.songsandhymns.org/hymns/detail/onward-christian-soldiers. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ Pierpoint, Claudia Roth (18 November 2002). "The New Yorker Archive". The Silver Spire, p.74. http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2002/11/18/021118fa_fact_pierpont. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ "Scran". Photograph of Crown of Thorns spire on Linlithgow Church. http://www.scran.ac.uk/database/record.php?usi=000-000-113-234-C. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ Archives of the architect, and information from George Brandon, chief engineer involved in maintenance of the Festival Hall, one of the buildings studied by Spashett during the design of this chapel

- ^ If found, the building plans and photographs should be sent to the RIBA Drawings and Archives Collection, London for safekeeping; the RIBA has said it would be pleased to have them.

- ^ The architect's archives (to be catalogued and donated to RIBA Archives in late 2009)

- ^ "BNET UK". Kent and Sussex Courier: Reward for finding chapel plans. 2 October 2009. http://findarticles.com/p/news-articles/kent-and-sussex-courier-the-tunbridge-wells-ed/mi_8138/is_20091002/reward-chapel-plans/ai_n51046836/. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- ^ a b c Church Army (1965). Programme: The Opening by her Royal Highness Princess Alexandra. Church Army Press, Cowley, Oxford. pp. 1–10.

- ^ The explanation of "modern conceptions of worship" may imply a central altar as in Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. However the Church Army unexpectedly installed pews and a west-end altar, as seen in a photo in Church Army Review, Editor Vera Burtt, June 1965, page 8. The interior white leather-cloth is now missing. The terrazzo floor is covered with a sprung wooden floor, which may also possibly serve to protect the original floor, however the terrazzo is still visible in the chapel lobby.

- ^ Unknown journalist (30 April 1965). "Princess Alexandra will love this new college". Blackheath Reporter: 7.

- ^ The same Blackheath Reporter 30 April 1965 p.7 article contains a large photo of the chapel being built, with the mosaicist at work on the window columns.

- ^ Hersey, George L.. "Google Books". Architecture and geometry in the age of the Baroque, p.212: illustration of Modular Man. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=F1Tl9ok-7_IC&pg=PA211&dq=Le+Corbusier+modular+man. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Bussagli, Marco. "Google Books". Understanding Architecture, p.95: citing Le Corbusier in connection with paraboloid roofs. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=fMfCkY6-9joC&pg=PA95&lpg=PA95&dq=Le+Corbusier+paraboloid+roof&source=bl&ots=WsV9lZO03E&sig=ho55VZztTcThzTYmpj6nnSnAzjs&hl=en&ei=qZlfSoPAGaaNjAfwvNniDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=7. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "SSQ". Kalzip helps the RAF go bold in the cold, 2006: description of drainage and roof flashing challenge of paraboloid roof. http://www.buildingdesign-news.co.uk/2007/21-Kalzip-Standing-seam-metal-roofing-roof-flashing-News-220507.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-16.[dead link]

- ^ a b Martin, Sarah; Tom Harper (May-June 2007). "Kansas Preservation Vol 29, no.3". House of Tomorrow. pp. 12–15. http://www.kshs.org/resource/ks_preservation/kpmayjun07.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-23.

- ^ "Building Talk". Waterproofing for hyperbolic paraboloid roof. 29 July 2008. http://www.buildingtalk.com/news/ico/ico129.html. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ "Imagazine". Contractors of the year: winner. 18 June 2008. http://www.imaroofer.com/docs/2008-06.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ "Capital Roofing". The roof repairers. http://www.capital-roofing.co.uk/. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ In 2009 this was blocked on the outside so appears black from the inside. See photographs on article page.

- ^ "Tate Online". The Vigil by John Pettie, 1884. https://www.tate.org.uk/servlet/ViewWork?cgroupid=999999961&workid=11526&searchid=10979. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ Mitchell, Esther (2002). "Essortment". Medieval History: The Vigil of Arms. http://www.essortment.com/all/vigil_rhvh.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ T. Leman Hare, ed (1934). The World's Greatest Paintings: one hundred selected masterpieces of famous art galleries. Long Acre, London WC2: Odhams Press Ltd. pp. Alphabetical by painters; not numbered..

- ^ Scott, Sir Walter. Essay on Chivalry.

- ^ i.e. the early meeting-room form

- ^ Paterson, Allen; Steven Wooster. "Google Books". Trees For Your Garden, page 56. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=FMhzj-J0FagC&pg=PA56&lpg=PA56&dq=fan+vaulting+trees&source=bl&ots=M-V-IR1RkA&sig=NoEgao2Ri0o8_Csk9vHYV1PzgXw&hl=en&ei=maFfSrrDApHQjAfzx8ngDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Now served by gas boilers: information from college staff.

- ^ Unknown journalist (6 March 1964). "Well and truly laid". The Mercury: 16.

- ^ a b The Times; Court Circular; "Thatched House Lodge, Richmond Park, May 6", page 16. 7 May 1965.

- ^ "The Times". Today's Arrangements: p.15, col.1.. 6 May 1965.

- ^ "The Edward Alleyn Club". Death of former club president (RGD (Russell) Vernon, MBE). 9 July 2009. http://www.edwardalleynclub.com/en/articles/?events=310. Retrieved 2009-07-16.[dead link]

- ^ a b Church Army editor Vera Burtt (June 1965). "Image: "The College Chapel"". Church Army Review: 8.

- ^ "Church Army Online". Some Key Dates: "1965 Wilson Carlile Training College opened in Blackheath". 2009. http://www.churcharmy.org.uk/pub/aboutus/KeyDates.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-17.[dead link]

- ^ "Sheffield Directory". Wilson Carlile College Of Evangelism: Information from college.. http://www.sheffielddirectory.co.uk/info/16193/. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ^ "Blackheath High School GDST". History (citing 1994 move to Vanburgh Park). http://www.blackheathhighschool.gdst.net/index.php?page=about/history/index.html. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ The programme incorrectly names Russell Vernon as architect: Spashett designed the build for Austin Vernon & Partners, of which Vernon was the director.

- ^ "RIBA archives catalogue". Views of modern buildings: churches (1975). http://www.architecture.com/LibraryDrawingsAndPhotographs/RIBALibrary/Catalogue.aspx. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "BomberCrew.com". Homepage. http://www.bombercrew.com/. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ As part of a Ministry of Works team, facilitating the repair of the rose window.

- ^ As part of a Ministry of Works team refurbishing for Princess Elizabeth and Prince Philip.

- ^ For the Ministry of Works.

- ^ Archives of the architect.

- ^ asayburn (18 November 2008). "Dulwich on View". More Talking Houses: citations of Dulwich houses designed by Austin Vernon. http://dulwichonview.org.uk/2008/11/18/more-talking-houses/. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Information from the archivist at Gorton Monastery, Manchester

- ^ "Canterbury.gov.uk". Letter from Geering & Colyer dated 10 February 1978, citing E.T. Spashett ARIBA as architect. http://www2.canterbury.gov.uk/planning/dcn/CA/__/77/_0/07/94.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

External links

- Youtube video panorama of interior of chapel

- Advisory Board for Redundant Churches: Criteria for determining heritage values and the scope for change in closed Anglican churches

- Greenwich Heritage Centre: local archives covering Blackheath area.

- Church Army online

- Blackheath High School: virtual tour and videos

- Greenwich Council: planning and building department

- 20th Century Society: society for preservation of modern buildings

- RIBA archives

Categories:- Chapels in London

- Former churches in London

- Religious buildings completed in 1965

- Churches in Greenwich

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.