- Non-aggression principle

-

The non-aggression principle (also called the non-aggression axiom, the anti-coercion principle, the zero aggression principle, the non-initiation of force), or NAP for short, is a moral stance which asserts that aggression is inherently illegitimate. Aggression, for the purposes of the NAP, is defined as the initiation or threatening of violence against a person or legitimately owned property of another. Specifically, any unsollicited actions of others that physically affect an individual’s property, including that person’s body, no matter if the result of those actions is damaging, beneficiary or neutral to the owner, are considered violent when they are against the owner’s free will and interfere with his right to self-ownership. Supporters of NAP use it to demonstrate the immorality of theft, vandalism, assault, and fraud. In contrast to pacifism, the non-aggression principle does not preclude violence used in self-defense.[1]

Many supporters argue that NAP opposes such policies as victimless crime laws, taxation, and military drafts. NAP has historically been a prominent issue within libertarianism. Though not completely without controversy NAP represents the backbone of present day libertarian political philosophy.[2]

Contents

History

The principle has a long tradition but has been mostly popularized by anarchists and other schools of libertarianism.[3][4][5] Variations of it can be found in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, as well as in Eastern philosophies such as Taoism.[6]

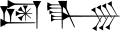

Historical formulations of the non-aggression principle Year Formulated by Formulation 300's BC Epicurus "Natural justice is a symbol or expression of usefullness, to prevent one person from harming or being harmed by another."[7] 900's Abu Mansur Al Maturidi, Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya, Averroes These Islamic theologians and philosopher wrote that man could rationally know that man had a right to life and property. early 1200's Ibn Tufayl In Hayy ibn Yaqzan the Islamic philosopher discussed the life story of a baby living alone without prior knowledge who discovered natural law, and natural rights, which obliged man not to coerce against another's life or property. Ibn Tufayl influenced Locke's notion of Tabula Rasa.[8] 1618 John Locke In Second Treatise on Government he wrote "Being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions."[9] 1682 Samuel von Pufendorf In On the Duty of Man and Citizen he wrote "Among the absolute duties, i.e., of anybody to anybody, the first place belongs to this one: let no one injure another. For this is the broadest of all duties, embracing all men as such."[10] 1722 William Wollaston In The Religion of Nature Delineated he formulated "No man can have a right to begin to interrupt the happiness of another." This formulation emphasized "begin" to distinguish aggressive disturbances from those in self-defense ("...yet every man has a right to defend himself and his against violence, to recover what is taken by force from him, and even to make reprisals, by all the means that truth and prudence permit.") 1790 Mary Wollstonecraft In "A Vindication of the Rights of Men" Mary Wollstonecraft states: "The birthright of man ... is such a degree of liberty, civil and religious, as is compatible with the liberty of every other individual with whom he is united in a social compact, and the continued existence of that compact." 1816 Thomas Jefferson "Rightful liberty is unobstructed action according to our will within limits drawn around us by the equal rights of others. I do not add 'within the limits of the law', because law is often but the tyrant's will, and always so when it violates the rights of the individual." and "No man has a natural right to commit aggression on the equal rights of another, and this is all from which the laws ought to restrain him." (Thomas Jefferson to Francis Gilmer, 1816) 1851 Herbert Spencer The law of equal freedom: "Every man is free to do that which he wills, provided he infringes not the equal freedom of any other man." This notion of equal freedom goes back to earlier liberal thought. 1859 John Stuart Mill The harm principle formulated in On Liberty, states that "the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others". 1961 Ayn Rand In an essay called "Man's Rights" in the book "The Virtue of Selfishness" she formulated "The precondition of a civilized society is the barring of physical force from social relationships. ... In a civilized society, force may be used only in retaliation and only against those who initiate its use." Note that she stipulated the context - civilized society.[11][12][13] 1963 Murray Rothbard "No one may threaten or commit violence ('aggress') against another man's person or property. Violence may be employed only against the man who commits such violence; that is, only defensively against the aggressive violence of another. In short, no violence may be employed against a nonaggressor. Here is the fundamental rule from which can be deduced the entire corpus of libertarian theory." Cited from "War, Peace, and the State" (1963) which appeared Egalitarianism as a Revolt Against Nature and Other Essays[14] Natural law theorist Murray Rothbard traces the non-aggression principle to natural law theorist St. Thomas Aquinas and the early Thomist scholastics of the Salamanca school.[15] This, in turn, may be seen in relation to Aquinas' view on greed, "a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things", and on envy, which be defined as "sorrow for another's good" (cf. Seven deadly sins).

Early formulations that use terms such as "harm" or "injury," such as those of Epicurus and Mill above, are today generally considered imprecise. "Harm" and "injury" are too subjective; one man's harm may be another man's benefit. For example, a squatter may make "improvements" that the owner considers detrimental. Modern formulations avoid such subjectivity by formulating the NAP in terms of individual rights or observable conduct (initiation of force/violence).

Justifications

The principle has been derived by various philosophical approaches, including:

- Argumentation ethics: A type of argument that attempts to establish normative or ethical truths by examining the presuppositions of discourse. Some philosophers, such as Stefan Molyneux, have argued that the non-aggression principle is valid because it is demonstrated to be correct by the act of argumentation.

- Natural law: Some derive non-aggression from self-ownership or sovereignty of the individual, such as Josiah Warren, Lysander Spooner, and Murray Rothbard.

- Social contract: The social contract is an intellectual device intended to explain the appropriate relationship between individuals and their governments. Social contract arguments assert that individuals unite into political societies by a process of mutual consent, agreeing to abide by common rules and accept corresponding duties to protect themselves and one another from violence and other kinds of harm.

- Right to life: Some philosophers, such as Ayn Rand, have argued that the non-aggression principle is derived from the right to life (see Objectivism).

Some consequentialist libertarians promote the non-aggression principle by basing its advocacy on forms of consequentialism such as rule utilitarianism and rule egoism. These utilitarians do not believe that it is categorically immoral to engage in aggression, but because they believe situations where aggression would lead to the best consequences are rare, they promote the non-aggression principle with the justification that if others accept it as a rule it would lead to better consequences than if they did not accept it as a rule. They believe the consequences of advocating the rule are superior to advocating that other individuals attempt to calculate each of their own actions to determine whether aggression or non-aggression would lead to better consequences.

Other consequentialist libertarians do not promote the non-aggression principle at all; they simply believe that allowing a very large scope of political and economic liberty results in the maximum well-being or efficiency for a society, even if securing this liberty involves some governmental actions that would be considered violations of the non-aggression principle. It just so happens that these actions are limited in the free society they envision. This type of libertarianism is associated with Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek.[16]

Definition issues

Abortion

Many supporters and opponents of abortion rights justify their position on NAP grounds. The central question to determine whether or not abortion is consistent with NAP is at what stage of development a fertilized human egg cell can be considered a human being. Some supporters of NAP argue this occurs at the moment of conception.[17]

Objectivist philosopher Leonard Peikoff has argued that a fetus has no rights over its host because it is a parasite.[18] Pro-choice libertarian Murray Rothbard has the same stance.[19] Pro-life libertarians, however, state that because the parents were actively involved in giving life to another human being, they are responsible for the position it is in and they are not allowed to kill it with abortive techniques.

Animal rights

Supporters generally argue that NAP only applies to humans, because humans generally have a free will and a self-conscious and rational mind, as well as a moral understanding. Most humans can therefore understand NAP and can be held accountable for their actions. Some critics claim that although these abilities are common they are not universal characteristics of the species. Young children and mentally handicapped persons may not have them (i.e. a person in a coma). When NAP applies to them as well as to normal people, as supporters of NAP agree, critics state that logically NAP should apply to all life forms with similar characteristics (see the Argument from Marginal Cases). This stance would lead to similar rights for sufficiently intelligent animals.[20] The argument extends to intelligent artificial life, such as AI computers and AI robots.[21]

Intellectual property rights

NAP is defined as applicable to any unauthorized actions towards a person’s physical property. Supporters of NAP disagree on whether it should apply to intellectual property (IP) as well.[22] Those who think not claim IP can be copied by others without any harm to the originator.[23] Those who think that NAP should be applied to IP in the same way as to physical property argue that all IP is somehow sublimated in physical property and that any owner has the right to determine what is done with his physical property.[24]

For example, if a software engineer writes a program on his own computer a copy of this program can only be obtained by using the engineer’s computer (either directly or remote via the internet). If the engineer then burns his program onto a DVD-ROM and sells this DVD to a third party he may sell this product unconditionally (i.e. the sale is free of any restrictions for the DVDs use) or, as would be normal in most cases, under specific conditions (i.e. the sale only transfers user rights and limited copyright). In the latter case, unauthorized copying would violate NAP as the engineer co-owns the DVD and a third party cannot make a copy without using the engineer’s property.

Interventions

Though NAP is meant to guarantee an individual’s sovereignty libertarians greatly differ on the conditions under which NAP applies. Especially unsollicited intervention by others, either to prevent society from being harmed by the individual’s actions or to prevent an incompetent individual from being harmed by his or her own (in)actions, is an important issue.[25] The debate centers on topics like the age of consent for children [26][27][28], intervention counseling (i.e. for addicted persons, or in case of domestic violence) [29][30], medical assistance (i.e. prolonged life support vs euthanasia in general and for the senile or comatose in particular) [31][32], human organ trade [33][34][35], state paternalism (including economic intervention) [36][37][38] and foreign intervention by states [39][40]. Other discussion topics on whether intervention is in line with NAP include nuclear weapons proliferation [41][42][43], and human trafficking and (illegal) immigration [44][45][46].

States

Some supporters justify the state on the grounds that anarchism implies that the non-aggression principle is optional because the enforcement of laws is open to competition.[citation needed] Anarcho-capitalists point out that the state suffers from similar failures because corruption and corporatism, as well as lobby group clientelism in democracies, favor only certain people or organizations. Anarcho-capitalists generally argue that the state violates the non-aggression principle by its nature because governments use force against those who have not stolen private property, vandalized private property, assaulted anyone, or committed fraud.[47][48][49]

Panarchists view a state as compatible with NAP as long as citizenship is not compulsory and all its citizens support its governance voluntarily. Statists, on the other hand, claim a state has legal jurisdiction over a certain area of land, or even owns that land. In that case NAP is not violated if a state imposes rules and regulations, any, as long as people entering the area are aware of these conditions and those already inside who disagree with unilaterally changed conditions are free to leave. The anarcho-capitalist argument that persons born in the land area owned or regulated by a state never were able to agree with the state's conditions and have no obligation to comply usually is countered by the statist argument that as the parents agreed to submit their child to these conditions of stay the child can only hold its parents responsible, not the state.

Taxation

Some libertarians see taxes as a violation of NAP while others argue that because of the free-rider problem in case security is a public good, enough funds would not be obtainable by voluntary means to protect individuals from aggression of a greater severity. They therefore accept taxation, and consequently a breach of NAP with regard to any free-riders, as long as no more is levied than is necessary to optimise protection of individuals against aggression.[citation needed]

Voluntarists such as anarcho-capitalists, on the other hand, claim that the protection of individuals against aggression is a service like any other and that it can be supplied by the free market much more effectively and efficiently than by a government monopoly. Their approach, based on proportionality in justice and damage compensation, argues that full restitution is compatible with both retributivism and a utilitarian degree of deterrence in order to uphold NAP in society.[50][51][52] They extend their argument to all public goods and services that require taxation, like security offered by dikes.[53] Geolibertarians argue a land value tax is compatible with NAP.

Criticisms

NAP faces two kinds of criticism: the first holds that the principle is immoral, the second argues that it is impossible to apply consistently in practice; respectively, consequentialist criticisms and inconsistency criticisms.

Consequentialist criticisms

Main article: ConsequentialismEthics

Some critics argue that the non-aggression principle is unethical because it opposes the initiation of force even when the results of such initiation would be better (though not necessarily for each and every individual involved) than any other course of action. Suppose, for example, that you could save a million lives by killing one innocent person. The non-aggression principle holds that you should not kill that person. However, this leads to a million deaths. While such extreme situations are unlikely, critics argue that milder forms of the same dilemma (for example, the choice between taking away part of a wealthy person's property or allowing a poor person to starve) are common.[citation needed]

One response to this argument by supporters is that the morality of killing one innocent person to save one million lives depends on the context. If someone threatens to kill one million lives unless an innocent person is killed, then it would be immoral to kill that person. However, if the failure to kill an innocent person would lead to millions of deaths because of a virus they carry, this person is initiating force against others, albeit without their knowledge. Furthermore, opponents of NAP must demonstrate why it is preferable for a poor person not to starve at the expense of a wealthy person's property before the argument can be evaluated.[citation needed] Another response to this argument would be that no one has a positive right to be saved. Some critics see the denial of positive rights as unethical but most libertarians argue that positive rights conflict with the right to self-ownership and self-determination of every individual and would legitimize some form of slavery.[54]

Other critics state that NAP is unethical because it legitimizes non-physical violence, such as mental battering, defamation, and boycotting or discrimination. If a victim thus provoked would turn to physical violence, according to NAP, he would be labeled an aggressor. Supporters of NAP, however, state that defamation constitutes freedom of speech and the boycotting or discrimination that may follow constitutes other people's freedom to deal with whoever they like. Supporters also state that individuals most of the time voluntarily engage in situations that may cause mental battering. Some supporters point out that mental battering, when it cannot be avoided, comes down to unauthorized physical overload of the senses (i.e. eardrum and retina) and NAP does apply.

Innocent persons problem

Some critics use the example of the trolley problem to invalidate NAP. In case of the runaway trolley, headed for five victims tied to the track, NAP does not allow a trolley passenger to flip the switch that diverts the trolley to a different track if there is a person tied to that track. That person would have been unharmed if nothing was done, therefore by flipping the switch NAP is violated. Another example often cited by critics is human shields.

Some supporters argue that no one initiates force if their only option for self-defense is to use force against a greater number of people as long as they were not responsible for being in the position they are in. Murray Rothbard's and Walter Block's formulations of NAP avoid these objections by either specifying that the NAP applies only to a civilized context (and not 'lifeboat situations') or that it applies only to legal rights (as opposed to general morality). Thus a starving man may, in consonance with general morality, break into a hunting cabin and steal food, but nevertheless he is aggressing, i.e. violating the NAP, and (by most rectification theories) should pay compensation.[55] Critics argue that the legal rights approach might allow people who can afford to pay a sufficiently large amount of compensation to get away with murder. They point out that local law, though based on NAP, may vary from proportional compensation to capital punishment to no compensation at all.[52]

Supporters generally argue that any harm done to innocent persons or any other collateral damage in these cases is done by whoever of whatever caused this situation to occur. In this view, if the threatened party harms the innocent persons, NAP is not violated. Furthermore, some supporters argue that actions that minimize harm are consistent with NAP.

Inconsistency criticisms

Some critics point out that almost every patch of land on Earth was stolen (i.e. obtained through initiation of force) at some point in its history. The stolen land was later inherited or sold until it reached its present owners. Thus, property over land and natural resources is based on the initiation of force. Among those who make this argument, some claim that private property over natural resources is unique in being based on the initiation of force, while others hold that, by extension, private property over all goods derives from violence, because natural resources are required in the production of all goods.[citation needed]

Some supporters respond with the "water under the bridge" argument: that transgressions of the past cannot all be rectified, and that an act of theft which happened long ago can reasonably be ignored. Critics argue that this implies that peaceful possession of property in the present legitimizes theft and/or trespass in the past. This requires a "cutoff" point: a point in time when illegitimate property becomes legitimate property. Some critics argue that any such point is arbitrary. Some supporters respond that property can only have a legal owner as long as there are no conflicting ownership claims to that property. The “cutoff” point, therefore, is when the owners who’s property has been stolen drop their claim because property that has no ownership claims at all is free for anyone to homestead.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Walter Block. "The Non-Aggression Axiom of Libertarianism (LewRockwell.com, February 17, 2003)". http://www.lewrockwell.com/block/block26.html. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ Phred Barnet. "The Non-Aggression Principle (Americanly Yours, April 14, 2011)". http://americanlyyours.com/2011/04/14/the-non-aggression-principle/. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Charles Murray, David Friedman, David Boaz, and R.W. Bradford. "Freedom: What’s Right vs What Works (Liberty Magazine, January 2005, Vol 15 No 1, pp. 31-39)". http://libertyunbound.com/sites/files/printarchive/Liberty_Magazine_January_2005.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Walter Block. "Jonah Goldberg and the Libertarian Axiom on Non-Aggression (LewRockwell.com, June 28, 2001)". http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig/block1.html. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ US LP. "”Our vision is for a world in which all individuals can freely exercise the natural right of sole dominion over their own lives, liberty and property” (US Libertarian Party Membership Form)". http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig/block1.html. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Murray N. Rothbard. "Libertarianism in Ancient China (Mises Daily, December 23, 2009)". http://mises.org/daily/3903. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Epicurus. "The Internet Classics Archives: Principal Doctrines (translated by Robert Drew Hicks)". http://classics.mit.edu/Epicurus/princdoc.html. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ G.A. Russell. "The 'Arabick' interest of the natural philosophers in seventeenth-century England (Brill Publishers, 1994, ISBN 9004094598, pp. 224-239)". http://books.google.co.uk/books/about/The_Arabick_interest_of_the_natural_phil.html?id=4H2fESItCVIC. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ John Lock. "Second Treatise of Civil Government (1690, 1764)". http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/phl302/texts/locke/locke2/locke2nd-a.html#Sect.%206.. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Samuel von Pufendorf. "On the Duty of Man and Citizen According to the Natural Law (Cambridge University, 1682, Book I, Chapter VI)". http://www.constitution.org/puf/puf-dut_106.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Ayn Rand. "The Nature of Government (December 1963, from The Virtue of Selfishness, 1961, 1964)". http://www.ccsindia.org/ccsindia/lssreader/2lssreader.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Ayn Rand. "The Roots of War (June 1966, excerpts)". http://www.freedomkeys.com/ar-rootsofwar.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Ayn Rand. "Faith and Force: The Destroyers of the Modern World (1960, 1967, excerpts)". http://freedomkeys.com/faithandforce.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Murray N. Rothbard. "War, Peace, and the State (April 1963)". http://www.lewrockwell.com/rothbard/rothbard26.html. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Murray N. Rothbard. "Introduction to Natural Law (The Ethics of Liberty, 1982, Chapters 1-5)". http://www.lewrockwell.com/rothbard/rothbard135.html. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ Norman P. Barry. "Review Article: The New Liberalism (British Journal of Political Science, Vol. 13, No. 1, January 1983, pp. 93-123)". http://www.jstor.org/pss/193781. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Various authors. "Are libertarians pro choice or pro life? (Libertarian FAQ Wikipage, January 2, 2010)". http://www.libertarianfaq.org/index.php?title=Are_libertarians_pro_choice_or_pro_life%3F. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Leonard Peikoff. "Abortion Rights are Pro-Life". http://www.peikoff.com/essays_and_articles/abortion-rights-are-pro-life/. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ Murray N. Rothbard. "For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto (1973, 1978, 2002 online ed, Chapter 6)". http://mises.org/rothbard/newlibertywhole.asp#p94. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ David Graham. "A Libertarian Replies to Tibor Machan"s "Why Animal Rights Don"t Exist" (Strike The Root, March 28, 2004)". http://www.strike-the-root.com/4/graham/graham1.html. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ BestDeathScenes. "Best Death Scenes: HAL 9000 (YouTube.com video, March 23, 2009)". http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=px0c4Tgg6gg. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ^ Wendy McElroy. "Intellectual Property: The Late Nineteenth Century Libertarian Debate (Libertarian Alliance, 1995, ISBN 1 85637 281 2)". http://www.libertarian.co.uk/lapubs/libhe/libhe014.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ N. Stephan Kinsella. "Against Intellectual Property (Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, Spring 2001, pp. 1-53)". http://mises.org/journals/jls/15_2/15_2_1.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Lysander Spooner. "The Law of Intellectual Property: An Essay on the Right of Authors and Inventors to a Perpetual Property in Their Ideas (Bella Marsh, Boston, 1855)". http://www.lysanderspooner.org/intellect/contents.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Nathaniel Branden. "Reflections on Self-Responsibility and Libertarianism (The Freeman April 2001, Vol. 51, No. 4)". http://www.thefreemanonline.org/featured/reflections-on-self-responsibility-and-libertarianism/. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Wayne Allyn Root. "Anarchism, Age of Consent Laws and the Dallas Accord (Crazy for Liberty, May 7, 2008)". http://crazyforliberty.com/2008/05/07/anarchism-age-of-consent-laws-and-the-dallas-accord-wayne-allyn-root.aspx. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Lonely Libertarian. "Age of Consent (The Lonely Libertarian, April 25, 2008)". http://lonelylibertarian.blogspot.com/2008/04/age-of-consent.html. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Max O’Connor. "Sex, Coercion, and the Age of Consent (Libertarian Alliance, 1981, ISBN 1 85637 190 5)". http://www.thedegree.org/polin010.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ M J P A Janssens et al.. "Pressure and coercion in the care for the addicted: ethical perspectives (Journal of Medical Ethics, 2004, No. 30, pp. 453-458)". http://jme.bmj.com/content/30/5/453.full.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Michael J. Formica. "Addiction, Self-responsibility and the Importance of Choice: Why AA doesn’t work (Psychology Today, June 3, 2010)". http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/enlightened-living/201006/addiction-self-responsibility-and-the-importance-choice. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ John Hospers. "Libertarianism and Legal Paternalism (The Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. IV, No. 3, Summer 1980, pp. 255-265)". http://mises.org/journals/jls/4_3/4_3_2.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ W E Messamore (ed.). "A Euthanasia First in the Netherlands (The Humble Libertarian, November 9, 2011)". http://www.humblelibertarian.com/2011/11/euthanasia-first-in-netherlands.html. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Danny Frederick. "A Competitive Market in Human Organs (Libertarian Papers, Vol. 2, No. 27, 2010, pp. 1-21, online at libertarianpapers.org )". http://independent.academia.edu/DannyFrederick/Papers/159192/A_Competitive_Market_in_Human_Organs. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Graeme Klass. "Organ Trading (The Libertarian Engineer, April 6, 2011)". http://www.graemeklass.com/economics/organ-trading/. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ John Gordon. "The humanity experiment has mixed results: Organ trade and enslaving the disabled (Gordon’s Notes, September 9, 2011)". http://notes.kateva.org/2011/09/humanity-experiment-has-mixed-results.html. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Cass Sunstein. "Libertarian Paternalism (University of Chicago Law School, January 20, 2007)". http://uchicagolaw.typepad.com/faculty/2007/01/libertarian_pat.html. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ David Gordon. "Libertarian Paternalism (Mises Daily, May 21, 2008)". http://mises.org/daily/2965. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Ilya Somin. "Richard Thaler Responds to Critics of Libertarian Paternalism (The Volokh Conspiracy April 15, 2010)". http://volokh.com/2010/04/19/richard-thaler-responds/. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ John Stuart Mill. "A Few Words On Non-Intervention (Libertarian Alliance reprint of J.S. Mill’s essay from Fraser’s Magazine, 1859)". http://www.libertarian.co.uk/lapubs/forep/forep008.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ George Dance. "Non-Intervention (The continuing rEVOlution, May 20, 2011)". http://www.nolanchart.com/article8684-nonintervention.html. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Walter Block & Matthew Block. "Toward a Universal Libertarian Theory of Gun (Weapon) Control: A Spatial and Geographycal Analysis (Ethics, Place and Environment, Vol. 3, No. 3, May 2000, pp.289-298)". http://www.walterblock.com/wp-content/uploads/publications/theory_gun_control.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Michael Gilson-De Lemos. "Who should Own Nuclear Weapons (Best Syndication, November 25, 2005)". http://www.bestsyndication.com/2005/A-H/DAVIS-Mike/112505_nuclear_weapons.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Various authors. "How would markets handle nuclear weapons proliferation and safety issues? (Reddit forum discussion, April 2011)". http://www.reddit.com/r/Libertarian/comments/gp7hy/currently_nuclear_weapons_are_heavily_regulated/. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Per Bylund. "The Libertarian Immigration Conundrum (Mises Daily, December 8, 2005)". http://mises.org/daily/1980. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Ken Schoolland. "Immigration: Controversies, Libertarian Principles and Modern Abolition (International Society for Individual Liberty, 2001)". http://www.isil.org/resources/libertydocs/immigration.html. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Johan Norberg. "Globalisation is Good (Channel 4 UK documentary, 2003, on Google video)". http://video.google.nl/videoplay?docid=5633239795464137680. Retrieved 2011-11-22.

- ^ Roderick T. Long. "Market Anarchism as Constitutionalism (Anarchism/Minarchism, 2008, Chapter 9)". http://praxeology.net/Anarconst2.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ Geoffrey Allen Plauché (Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA). "On the Social Contract and the Persistence of Anarchy (American Political Science Association, 2006)". http://gaplauche.com/docs/persistentanarchyapsa2006.pdf. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- ^ Stefan Molyneux. "The Stateless Society (LewRockwell.com, October 24, 2005)". http://www.lewrockwell.com/orig6/molyneux1.html. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ J. C. Lester. "Why Libertarian Restitution Beats State-Retribution and State-Leniency (2005)". http://www.la-articles.org.uk/libertarian_restitution.htm. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ Murray N. Rothbard. "Punishment and Proportionality (The Ethics of Liberty, 1982, Chapter 13)". http://mises.org/daily/2496. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ a b David D. Friedman. "Police, Courts and Law – On the Market (The Machinery of Freedom, 1989, Chapter 29)". http://www.daviddfriedman.com/Libertarian/Machinery_of_Freedom/MofF_Chapter_29.html. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- ^ Philipp Bagus. "Can Dikes Be Private? : An Argument Against Public Goods Theory (Journal of Libertarian Studies, Vol. 20, No. 4, Fall 2006, pp. 21-40)". http://mises.org/daily/2537. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Henry Sturman. "Morality and Libertarianism (1999)". http://henrysturman.com/english/articles/morality.html. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- ^ Murray N. Rothbard. "Lifeboat Situations (The Ethics of Liberty, 1982, Chapter 20)". http://mises.org/daily/1628. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

See also

- Aggression

- Anarcho-capitalism and minarchism

- Economic intervention

- Harm principle

- Law of equal liberty

- Libertarian perspectives on foreign intervention

- Libertarian perspectives on revolution

- Natural law

- Nonviolence

- Pacifism

- Paternalism

- Public order crime

- Self ownership

- Taxation as theft

- Victimless crime

External links

- The Ethics of Liberty e-book by Murray Rothbard, Mises.org

- A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism e-book by Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Mises.org

- The Non-Aggression Axiom of Libertarianism by Walter Block, LewRockwell.com

- Against Utilitarianism; or, Why Not Violate Rights if it'd Do Good by Tibor Machan, Mises.org

- Economics and Its Ethical Assumptions by Roderick Long, Mises.org

- New Rationalist Directions in Libertarian Rights Theory by N. Stephan Kinsella, Mises.org

- The Philosophy of Liberty, an animated production, derives a libertarian philosophy from the principle of self-ownership. Central to this is the non-aggression principle.

Anarcho-capitalism

Features Aggression insurance · Crime insurance · Dispute resolution organization · Free-market roads · Jurisdictional arbitrage · Non-aggression principle · Polycentric law · Private defense agency · Private Governance · Self-ownership · Spontaneous orderCategories:- Libertarian theory

- Anarchist theory

- Anarcho-capitalism

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.