- Surgical suture

-

For other uses, see Suture (disambiguation).

Surgical suture is a medical device used to hold body tissues together after an injury or surgery. It generally consists of a needle with an attached length of thread. A number of different shapes, sizes, and thread materials have been developed over its millennia of history.

Contents

History

Through many millennia, various suture materials were used, debated, and remained largely unchanged. Needles were made of bone or metals such as silver, copper, and aluminum bronze wire. Sutures were made of plant materials (flax, hemp and cotton) or animal material (hair, tendons, arteries, muscle strips and nerves, silk, catgut). African cultures used thorns, and others used ant sutures by coaxing insects to bite wound edges with their jaws and subsequently twisting off the insects' heads.[1]

The earliest reports of surgical suture date back to 3000 BC in ancient Egypt, and the oldest known suture is in a mummy from 1100 BC. The first detailed description of a wound suture and the suture materials used in it is by the Indian sage and physician Sushruta, written in 500 BCE. The Greek "father of medicine" Hippocrates described rudimentary suture techniques, as did the later Roman Aulus Cornelius Celsus. The 2nd-century Roman physician Galen has been credited as the first to describe gut sutures,[1][verification needed] or alternatively the 10th-century Andalusian surgeon al-Zahrawi. Al-Zahrawi reportedly discovered the dissolving nature of catgut when his lute's strings were eaten by a monkey.[citation needed] The manufacturing process involved harvesting sheep intestines, the so called catgut suture, and was similar to that of strings for violins, guitar, and tennis racquets.

Joseph Lister introduced great change in suturing technique (as in all surgery) when he endorsed the routine sterilization of all suture threads. He first attempted sterilization with the 1860s "carbolic catgut," and chromic catgut followed two decades later. Sterile catgut was finally achieved in 1906 with iodine treatment.[1]

The next great leap came in the twentieth century. The chemical industry drove production of the first synthetic thread in the early 1930s, which exploded into production of numerous absorbable and non-absorbable synthetics. The first synthetic absorbable was based on polyvinyl alcohol in 1931. Polyesters were developed in the 1950s, and later the process of radiation sterilization was established for catgut and polyester. Polyglycolic acid was discovered in the 1960s and implemented in the 1970s.[1] Today, most sutures are made of synthetic polymer fibers. Silk and gut sutures are the only materials still - though rarely - in use from ancient times. In fact, gut sutures have been banned in Europe and Japan owing to concerns regarding Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy, though silk suture is still used in vascular and ENT (otolaryngology) procedures.

Needles

Traumatic needles are needles with holes or eyes which are supplied to the hospital separate from their suture thread. The suture must be threaded on site, as is done when sewing at home. Atraumatic needles with sutures comprise an eyeless needle attached to a specific length of suture thread. The suture manufacturer swages the suture thread to the eyeless atraumatic needle at the factory. There are several advantages to having the needle pre-mounted on the suture. The doctor or the nurse does not have to spend time threading the suture on the needle. More importantly, the suture end of a swaged needle is smaller than the needle body. In traumatic needles with eyes, the thread comes out of the needle's hole on both sides. When passing through the tissues, this type of suture rips the tissue to a certain extent, thus the name traumatic. Nearly all modern sutures feature swaged atraumatic needles.

There are several shapes of surgical needles. These include straight, 1/4 circle, 3/8 circle, 1/2 circle, 5/8 circle, compound curve, half curved (also known as ski), and half curved at both ends of a straight segment (also known as canoe). The ski and canoe needle design allows curved needles to be straight enough to be used in laparoscopic surgery, where instruments are inserted into the abdominal cavity through narrow cannulas.

Needles may also be classified by their point geometry; examples include:

- taper (needle body is round and tapers smoothly to a point)

- cutting (needle body is triangular and has a sharpened cutting edge on the inside)

- reverse cutting (cutting edge on the outside)

- trocar point or tapercut (needle body is round and tapered, but ends in a small triangular cutting point)

- blunt points for sewing friable tissues

- side cutting or spatula points (flat on top and bottom with a cutting edge along the front to one side) for eye surgery

Finally, atraumatic needles may be permanently swaged to the suture or may be designed to come off the suture with a sharp straight tug. These "pop-offs" are commonly used for interrupted sutures, where each suture is only passed once and then tied.

Sutures can withstand different amounts of force based on their size; this is quantified by the U.S.P. Needle Pull Specifications.

Thread

Materials

Further information: Suture materials comparison chartSuture thread is made from numerous materials. The original sutures were made from biological materials, such as catgut suture and silk. Most modern sutures are synthetic, including the absorbables polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid, and polydioxanone as well as the non-absorbables nylon and polypropylene. Newer still is the idea of coating sutures with antimicrobial substances to reduce the chances of wound infection.[citation needed] Sutures come in very specific sizes and may be either absorbable (naturally biodegradable in the body) or non-absorbable. Sutures must be strong enough to hold tissue securely but flexible enough to be knotted. They must be hypoallergenic and avoid the "wick effect" that would allow fluids and thus infection to penetrate the body along the suture tract.

Absorbability

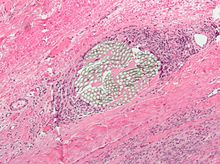

All sutures are classified as either absorbable or non-absorbable depending on whether the body will naturally degrade and absorb the suture material over time. Absorbable suture materials include the original catgut as well as the newer synthetics polyglycolic acid (Biovek), polylactic acid, polydioxanone, and caprolactone. They are broken down by various processes including hydrolysis (polyglycolic acid) and proteolytic enzymatic degradation. Depending on the material, the process can be from ten days to eight weeks. They are used in patients who cannot return for suture removal, or in internal body tissues. In both cases, they will hold the body tissues together long enough to allow healing, but will disintegrate so that they do not leave foreign material or require further procedures. Occasionally, absorbable sutures can cause inflammation and be rejected by the body rather than absorbed.

Non-absorbable sutures are made of special silk or the synthetics polypropylene, polyester or nylon. Stainless steel wires are commonly used in orthopedic surgery and for sternal closure in cardiac surgery. These may or may not have coatings to enhance their performance characteristics. Non-absorbable sutures are used either on skin wound closure, where the sutures can be removed after a few weeks, or in stressful internal environments where absorbable sutures will not suffice. Examples include the heart (with its constant pressure and movement) or the bladder (with adverse chemical conditions). Non-absorbable sutures often cause less scarring because they provoke less immune response, and thus are used where cosmetic outcome is important. They must be removed after a certain time, or left permanently.

Sizes

Suture sizes are defined by the United States Pharmacopeia (U.S.P.). Sutures were originally manufactured ranging in size from #1 to #6, with #1 being the smallest. A #4 suture would be roughly the diameter of a tennis racquet string. The manufacturing techniques, derived at the beginning from the production of musical strings, did not allow thinner diameters. As the procedures improved, #0 was added to the suture diameters, and later, thinner and thinner threads were manufactured, which were identified as #00 (#2-0 or #2/0) to #000000 (#6-0 or #6/0).

Modern sutures range from #5 (heavy braided suture for orthopedics) to #11-0 (fine monofilament suture for ophthalmics). Atraumatic needles are manufactured in all shapes for most sizes. The actual diameter of thread for a given U.S.P. size differs depending on the suture material class.

-

USP

designationCollagen

diameter (mm)Synthetic absorbable

diameter (mm)Non-absorbable

diameter (mm)American

wire gauge11-0 0.01 10-0 0.02 0.02 0.02 9-0 0.03 0.03 0.03 8-0 0.05 0.04 0.04 7-0 0.07 0.05 0.05 6-0 0.1 0.07 0.07 38–40 5-0 0.15 0.1 0.1 35–38 4-0 0.2 0.15 0.15 32–34 3-0 0.3 0.2 0.2 29–32 2-0 0.35 0.3 0.3 28 0 0.4 0.35 0.35 26–27 1 0.5 0.4 0.4 25–26 2 0.6 0.5 0.5 23–24 3 0.7 0.6 0.6 22 4 0.8 0.6 0.6 21–22 5 0.7 0.7 20–21 6 0.8 19–20 7 18

Techniques

Placement

Sutures are placed by mounting a needle with attached suture into a needle holder. The needle point is pressed into the flesh, advanced along the trajectory of the needle's curve until it emerges, and pulled through. The trailing thread is then tied into a knot, usually a square knot or surgeon's knot. Sutures should bring together the wound edges, but should not cause indenting or blanching of the skin,[2] since the blood supply may be impeded and thus increase infection and scarring.[3][4] Sutured skin should roll slightly outward from the wound (eversion), and the depth and width of the sutured flesh should be roughly equal.[3] Placement varies based on the location, but the distance between each suture generally should be equal to the distance from the suture to the wound edge, in accordance with Jenkin's Rule.[4][5]

Many different techniques exist. The most common is the simple interrupted stitch;[6] it is indeed the simplest to perform and is called "interrupted" because the suture thread is cut between each individual stitch. The vertical and horizontal mattress stitch are also interrupted but are more complex and specialized for everting the skin and distributing tension. The running or continuous stitch is quicker but risks failing if the suture is cut in just one place; the continuous locking stitch is in some ways a more secure version. The chest drain stitch and corner stitch are variations of the horizontal mattress. Other stitches include the Figure 8 stitch and subcuticular stitch.

Removal

While some sutures are intended to be permanent, and others in specialized cases may be kept in place for an extended period of many weeks, as a rule sutures are a short term device to allow healing of a trauma or wound.

- "Different parts of the body heal at different speed. Common time to remove stitches will vary: facial wounds 3–5 days; scalp wound 7–10 days; limbs 10–14 days; joints 14 days; trunk of the body 7–10 days.[cite this quote]

- "Not all stitches must be removed. If a small area remains unhealed, notify the health care practitioner. Then if ordered, remove sutures from the healed area only."[cite this quote]

Expansions

A pledgeted suture is one that is supported by a pledget, that is, a small flat absorbent pad or piece of cloth, in order to protect a wound.[7]

Tissue adhesives

In recent years, topical cyanoacrylate adhesives ("liquid stitches"), a.k.a medicinal grade super glue, have been used in combination with, or as an alternative to, sutures in wound closure. The adhesive remains liquid until exposed to water or water-containing substances/tissue, after which it cures (polymerizes) and forms a flexible film that bonds to the underlying surface. The tissue adhesive has been shown to act as a barrier to microbial penetration as long as the adhesive film remains intact. Limitations of tissue adhesives include contraindications to use near the eyes and a mild learning curve on correct usage.

Cyanoacrylate is the generic name for cyanoacrylate based fast-acting glues such as methyl-2-cyanoacrylate, ethyl-2-cyanoacrylate (commonly sold under trade names like Superglue and Krazy Glue) and n-butyl-cyanoacrylate. Skin glues like Indermil and Histoacryl were the first medical grade tissue adhesives to be used, and these are composed of n-butyl cyanoacrylate. These worked well but had the disadvantage of having to be stored in the refrigerator, were exothermic so they stung the patient, and the bond was brittle. Nowadays, the longer chain polymer, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, is the preferred medical grade glue. It is available under various trade names, such as LiquiBand, SurgiSeal, FloraSeal, and Dermabond. These have the advantages of being more flexible, making a stronger bond, and being easier to use. The longer side chain types, for example octyl and butyl forms, also reduce tissue reaction. The use of common household super glue is not advisable.[citation needed]

See also

- Barbed suture

- Chitin

- Ligature

- Knots

- Sewing

- Surgical staple

- List of medical topics

- Steri strip

- Cyanoacrylate

References

- ^ a b c d "History of the Surgical Suture". B. Braun. 2009. http://www.sutures-bbraun.com/index.cfm?917A74A92A5AE6266700AD9ACBE9432C. Retrieved 24 Oct 2009.

- ^ Osterberg, B; Blomstedt, B (1979). "Effect of suture materials on bacterial survival in infected wounds: An experimental study". Acta Chir Scand 145: 431.

- ^ a b Macht, SD; Krizek, TJ (1978). "Sutures and suturing - Current concepts". Journal of Oral Surgery 36: 710.

- ^ a b Kirk, RM (1978). Basic Surgical Techniques. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- ^ Grossman, JA (1982). "The repair of surface trauma". Emergency Medicine 14: 220.

- ^ Lammers, Richard L; Trott, Alexander T (2004). "Chapter 36: Methods of Wound Closure". In Roberts, James R; Hedges, Jerris R. Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 671. ISBN 0-7216-9760-7.

- ^ mondofacto.com 05 Mar 2000

External links

Operations/surgeries and other procedures of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (ICD-9-CM V3 86, ICD-10-PCS 0H) Skin Hair Categories:- Stitches

- First aid

- Medical skills

- Injuries

- Traumatology

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.