- Saramaka

-

Saramaka

Total population 55,000 Regions with significant populations Suriname and French Guiana Languages Religion Saramaka Religion (80%), Christianity--Moravian, Catholic, Evangelical (20%)

Related ethnic groups Ndyuka, Matawai, Paramaka, Aluku (Boni), Kwinti

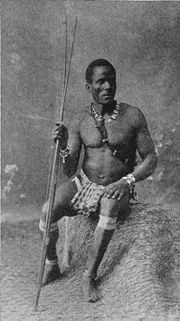

The Saramaka or Saramacca are one of six Maroon peoples (formerly called "Bush Negroes") in the Republic of Suriname. The word "Maroon" comes from the Spanish cimarrón, itself derived from an Arawakan root;[1] by the early 16th century it was used throughout the Americas to designate slaves who successfully escaped from slavery.[2]

Contents

Setting and language

Suriname, formerly called Dutch Guiana, has been independent from the Netherlands since 1975. The 55,000 Saramakas (some of whom live in neighboring French Guiana) are one minority within this multiethnic nation, which includes approximately 37 per cent Hindustanis (East Indian descendants of contract laborers brought in after the abolition of slavery); 31 per cent Creoles (descendants of Africans brought as slaves); 15 per cent Javanese (descendants of contract workers brought during the early 20th century from Indonesia); 3 per cent Chinese, Levantines, and Europeans; 2 per cent Amerindians; and 12 per cent Maroons. Together with the other Maroons in Suriname and French Guiana – the Ndyuka (55,000), and the Matawai, Paramaka, Aluku, and Kwinti (who together number some 18,000) – the Saramaka constitute by far the world's largest surviving population of Afro-American Maroons.[3]

Since their escape from slavery in the 17th and 18th centuries, Saramakas have lived along the upper Suriname River and its tributaries, the Gaánlío and the Pikílío. Since the 1960s they also live along the lower Suriname River in villages constructed by the colonial government and Alcoa after approximately half of tribal territory was flooded for a hydroelectric project built to supply electricity for an aluminum smelter. Today, about one third of Saramakas live in French Guiana, most having arrived since 1990.[4]

The Saramaka and the Matawai (in central Suriname) speak variants of a creole language called Saramaccan, and the Ndyuka, Paramaka, and Aluku, (in eastern Suriname), as well as the several hundred Kwinti, speak variants of another creole language, called Ndyuka. Both languages are historically related to Sranan-tongo (also called Nengre Tongo), the creole language of coastal Suriname. About 50 percent of the Saramaccan lexicon derives from various West and Central African languages, 20 percent from English (the language of the original colonists in Suriname), 20 percent from Portuguese (the language of the slave masters on many Suriname plantations), and the remaining 10 percent from Amerindian languages and Dutch.[5] The grammar resembles that of the other (lexically different) Atlantic creoles and derives from West African models.[6]

History

The ancestors of the Saramaka were among those Africans sold into slavery in the late 17th and early 18th centuries to work Suriname's sugar, timber, and coffee plantations. Coming from a variety of African peoples speaking many different languages, they escaped into the dense rainforest – individually, in small groups, and sometimes in great collective rebellions – where for nearly 100 years they fought a war of liberation. In 1762, a full century before the general emancipation of slaves in Suriname, they won their freedom and signed a treaty with the Dutch crown. Saramakas have a keen interest in the history of their formative years and preserve an unusually rich oral tradition, which has permitted innovative scholarly explorations that bring together oral and archival accounts.[7]

Like the other Suriname Maroons, the Saramaka lived almost as a state-within-a-state until the mid-20th century, when the pace of outside encroachments increased. During the late 1980s a civil war between Maroons and the military government of Suriname caused considerable hardship to the Saramakas and other Maroons. By mid 1989 approximately 3,000 Saramakas and 8,000 Ndyukas were living as temporary refugees in French Guiana, and access to the outside world had become severely restricted for many Saramaka in their homeland.[8] The end of the war in the mid-1990s initiated a period in which the national government largely neglected the needs of Saramakas and other Maroons and granted large timber and mining concessions to foreign multinationals (Chinese, Indonesian, Malaysian, and others) in traditional Saramaka territory but without consulting Saramaka authorities.[9] This period saw numerous changes both on the coast of Suriname and in Saramaka territory. U.S. Peace Corps volunteers took up residence in Saramaka villages, Brazilian gold-miners arrived on the Suriname river, and such activities as prostitution, casino gambling, and drug smuggling became major industries in coastal Suriname and elsewhere.[10]

In the mid 1990s, the Association of Saramaka Authorities initiated a complaint before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights to protect their land rights. In November, 2007, the Inter-American Court for Human Rights finally ruled in favor of the Saramaka people against the government of Suriname.[11] In this landmark decision, which establishes a precedent for all Maroon and indigenous peoples in the Americas, the Saramaka were granted collective rights to the lands on which their ancestors had lived since the early 18th century, including rights to decide about the exploitation of natural resources such as timber and gold within that territory. In addition, they were granted compensation from the government for damages caused by previous timber grants made to Chinese companies, paid into a special development fund now managed by Saramakas.[12]

Subsistence, economy, and the arts

Traditional villages, which average 100 to 200 residents, consist of a core of matrilineal kin plus some wives and children of lineage men.[13] Always located near a river, they are an irregular arrangement of small houses, open-sided structures, domesticated trees, an occasional chicken houses, various shrines, and scattered patches of bush. (In contrast, the so-called transmigration villages, built to house the 6,000 Saramakas displaced by the hydroelectric project, range up to 2,000 people, are laid out in a grid pattern, and in many cases are located far from the riverside.) Horticultural camps, which include permanent houses and shrines, are located several hours by canoe from each village, and are exploited by small groups of women related through matrilineal ties. Many women have a house in their own village, another in their horticultural camp, and a third in their husband's village. Men divide their time among several different houses, built at various times for themselves and for their wives. Traditional Saramaka houses are barely wide enough to tie a hammock and not much longer from front to back; with walls of planks and woven palm fronds and roofs of thatch or, increasingly, of corrugated metal, they are windowless but often have elaborately carved facades.[14] Since the Suriname civil war, an increasing number of houses have been built in coastal, Western style, using concrete as well as wood, and featuring windows and an expansive floor plan.

For more than two centuries, the economy has been based on full exploitation of the forest environment and on periodic work trips by men to the coast to bring back Western goods. For subsistence, Saramakas depend on shifting (swidden) horticulture, hunting, and fishing, supplemented by wild forest products such as palm nuts and a few key imports such as salt. Gardens are planted most heavily in dry (hillside) rice, but include other crops as well, such as cassava, taro, okra, maize, plantains, bananas, sugarcane, and peanuts. Domesticated trees such as coconut, orange, breadfruit, papaya, and calabash are mainly in the villages. There are no markets.

Until the late 20th century, Saramakas produced the great bulk of their material culture, much of it embellished with decorative detail. Men built the houses and canoes and carved a wide range of wooden objects for domestic use, such as stools, paddles, winnowing trays, cooking utensils, and combs. Women sewed patchwork and embroidered clothing and carved calabash bowls. Some men also produced baskets, and some women made pottery. Today, an increasing number of items, including clothing, are imported from the coast. Body cicatrization, practiced by virtually all Saramaka women as late as the 1970s and 80s, had become relatively uncommon by the turn of the century, but the numerous genres of singing, dance, drumming, and tale telling continue to be a vibrant part of Saramaka culture.[15]

Once the men have cleared and burned the fields, horticulture is mainly women's work. Hunting, with shotguns, is the responsibility of men, who do most of the fishing as well. Men have always devoted a large portion of their adult years to earning money in coastal Suriname or French Guiana to provide the Western goods considered essential to life in their home villages, such as shotguns and powder, tools, pots, cloth, hammocks, soap, kerosene, and rum. During the second half of the 20th century, small stores sprang up in many villages, and outboard motors, transistor radios, and tape recorders became common. Today, cell phones are ubiquitous and communication with Paramaribo, by both men and women, has vastly increased. And new economic opportunities in the gold industry – mining for men, prostitution for women – are currently being exploited.

Social organization

Saramaka society is firmly based on matrilineal principles. A clan (lo) – often several thousand individuals – consists of the matrilineal descendants of an original band of escaped slaves. It is subdivided into lineages (bee) – usually 50 to 150 people – descended from a more recent ancestress. Several lineages from a single clan constitute the core of every village.

Land is owned by these matrilineal clans (lo), based on claims staked out in the early 18th century as the original Maroons fled southward to freedom. Hunting and gathering rights belong to clan members collectively. Within the clan, temporary rights to land use for farming are negotiated by village headmen. The establishment of transmigration villages in the 1960s led to land shortages in certain regions, but the success of the Saramakas in their lawsuit against the government of Suriname will now permit them to manage their lands with less outside interference.

The application of complex marriage prohibitions (including bee exogamy) and preferences is negotiated through divination. Demographic imbalance owing to labor migration permits widespread polygyny. Although co-wives hold equal status, relations between them are expected to be adversarial. The Saramaka treat marriage as an ongoing courtship, with frequent exchanges of gifts such as men's woodcarving and women's decorative sewing. Although many women live primarily in their husband's village, men never spend more than a few days at a time in the matrilineal (home) village of a wife.[16]

Each house belongs to an individual man or woman, but most social interaction occurs outdoors. The men in each cluster of several houses, whether bee members or temporary visitors, eat meals together. The women of these same clusters, whether bee members or resident wives of bee men, spend a great deal of time in each others’ company, often farming together as well.

Matrilineal principles, mediated by divination, determine the inheritance of material and spiritual possessions as well as political offices. Before death, however, men often pass on specialized ritual knowledge (and occasionally a shotgun) to a son.

Each child, after spending its first several years with its mother, is raised by an individual man or woman (not a couple) designated by the bee, girls normally by women, boys by men. Although children spend most of their time with matrilineal kin, father-child relations are warm and strong. Gender identity is established early, with children taking on responsibility for sex-typed adult tasks as soon as they are physically able. Girls often marry by age 15, whereas boys are more often in their twenties when they take their first wife. Protestant missionary schools have existed in some villages since the 18th century; such elementary schools came to most villages only in the 1960s. Schools ceased to function completely during the Suriname civil war of the late 1980s and have been rebuilt only partially since.

Political organization and social control

The Saramaka people, like the other Maroon groups, are run by men. The 2007 ruling of the Inter-American Court for Human Rights helps define the spheres of influence in which the national government and Saramaka authorities hold sway.

Saramaka society is strongly egalitarian, with kinship forming the backbone of social organization. No social or occupational classes are distinguished. Elders are accorded special respect and ancestors are consulted, through divination, on a daily basis.

Since the 18th century treaty, the Saramaka have had a government-approved paramount chief (gaamá), as well as a series of headmen (kabiteni) and assistant headmen (basiá). Traditionally, the role of these officials in political and social control was exercised in a context replete with oracles, spirit possession, and other forms of divination, but the national government is intervening more frequently in Saramaka affairs (and paying political officials nominal salaries), and the sacred base of these officials’ power is gradually being eroded. These political offices are the property of clans (lo). Political activity is strongly dominated by men.

Council meetings (kuútu) and divination sessions provide complementary arenas for the resolution of social problems. Palavers may involve the men of a lineage, a village, or all Saramaka and treat problems ranging from conflicts concerning marriage or fosterage to land disputes, political succession, or major crimes. These same problems, in addition to illness and other kinds of misfortune, are routinely interpreted through various kinds of divination as well. In all cases, consensus is found through negotiation, often with a strong role being played by gods and ancestors. Guilty parties are usually required to pay for their misdeeds with material offerings to the lineage of the offended person. In the 18th century people found guilty of witchcraft were sometimes burned at the stake. Today, men caught In flagrante delicto with the wife of another man are either beaten by the woman's kinsmen or made to pay them a fine.

Aside from adultery disputes, which sometimes mobilize a full canoe-load of men seeking revenge in a public fistfight, intra-Saramaka conflict rarely surpasses the level of personal relations. The civil war that began in 1986, pitting Maroons against the national army of Suriname, brought major changes to the villages of the interior. Members of the "Jungle Commando" rebel army, almost all Ndyukas and Saramakas, learned to use automatic weapons and became accustomed to a state of war and plunder. Their reintegration into Saramaka (and Ndyuka) society has been difficult, though migration to the coast and French Guiana has provided a safety valve.

Belief system

Various religious beliefs encompass every aspect of Saramaka life.[17] Such decisions as where to clear a garden or build a house, whether to undertake a trip, or how to deal with theft or adultery are made in consultation with village deities, ancestors, forest spirits, and snake gods. The means of communication with these powers vary from spirit possession and the consultation of oracle-bundles to the interpretation of dreams. Gods and spirits, which are a constant presence in daily life, are also honored through frequent prayers, libations, feasts, and dances. The rituals surrounding birth, death, and other life crises are extensive, as are those relating to more mundane activities, from hunting a tapir to planting a rice field. Today about 25 per cent of Saramaka are nominal Christians – mainly Moravian (some since the mid 18th century), but others Roman Catholic and, increasingly today, evangelicals of one or another kind.

The Saramaka world is populated by a wide range of supernatural beings, from localized forest spirits and gods that reside in the bodies of snakes, vultures, jaguars, and other animals to ancestors, river gods, and warrior spirits. Within these categories, each supernatural being is named, individualized, and given specific relationships to living people. Intimately involved in the ongoing events of daily life, these beings communicate to humans mainly through divination and spirit possession. Kúnus are the avenging spirits of people or gods who were wronged during their lifetime and who pledge themselves to eternally tormenting the matrilineal descendants and close matrilineal kinsmen of their offender. Much of Saramaka ritual life is devoted to their appeasement. The Saramaka believe that all evil originates in human action; not only does each misfortune, illness, or death stem from a specific past misdeed, but every offense, whether against people or gods, has eventual consequences. The ignoble acts of the dead intrude daily on the lives of the living; any illness or misfortune calls for divination, which quickly reveals the specific past act that caused it. Rites are then performed in which the ancestors speak, the gods dance, and the world is once again made right.

Major village- and clan-owned shrines that serve large numbers of clients, the various categories of possession gods, and various kinds of minor divination are the preserve of individual specialists who supervise rites and pass on their knowledge before death. A large proportion of Saramakas have some kind of specialized ritual expertise, which they occasionally exercise, and for which they are paid in cloth, rum, or, increasingly, cash.

Saramaka ceremonial life is not determined by the calendar, but rather regulated by the occurrence of particular misfortunes, interpreted through divination. The most important ceremonies include those surrounding funerals and the appeasement of ancestors, public curing rites, rituals in honor of kúnus (in particular snake gods and forest spirits), and the installation of political officials.

Every case of illness is believed to have a specific cause that can be determined only through divination. The causes revealed vary from a lineage kúnu to sorcery, from a broken taboo to an ancestor's displeasure. Once the cause is known, rites are carried out to appease the offended god or ancestor (or otherwise right the social imbalance). Since the 1960s, Western mission clinics and hospitals have been used by most Saramaka as a supplement to their own healing practices. During the Suriname Civil War of the 1980s and 1990s, most of these facilities were destroyed and have only been very partially restored since.

The dead play an active role in the lives of the living. Ancestor shrines – several to a village – are the site of frequent prayers and libations, as the dead are consulted about ongoing village problems. A death occasions a series of complex rituals that lasts about a year, culminating in the final passage of the deceased to the status of ancestor. The initial rites, which are carried out over a period of one week to three months depending on the importance of the deceased, end with the burial of the corpse in an elaborately constructed coffin filled with personal belongings. These rites include divination with the coffin (to consult the spirit of the deceased) by carrying it on the heads of two men, feasts for the ancestors, all-night drum/song/dance performances, and the telling of folktales.[18] Some months later, a "second funeral" is conducted to mark the end of the mourning period and to chase the ghost of the deceased from the village forever. These rites involve the largest public gatherings in Saramaka and also include all-night drum/song/dance performances. At their conclusion, the deceased has passed out of the realm of the living into that of the ancestors.

Ethnographic studies

Ethnography among the Saramakas has been carried out by Melville and Frances Herskovits (during two summers in 1928 and 1929)[19] and by Richard and Sally Price (intermittently between 1966 and the present, in Suriname until 1986, in French Guiana thereafter). This late-20th century fieldwork complements the modern fieldwork carried out among other groups of Suriname Maroons, such as the Ndyuka ethnography of Bonno and Ineke Thoden van Velzen.[20]

Edward C. Green conducted fieldwork among the Matawais between 1970–73, with intermittent visits since. His dissertation focused on changes underway then in the matrilineal kinship and indigenous spiritual belief systems.

References

- Brunner, Lisl. 2008. "The Rise of Peoples’ Rights in the Americas: The Saramaka People Decision of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights." Chinese Journal of International Law 7:699-711.

- "Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname." Inter-American Court for Human Rights (ser. C). No. 172 (28 November 2007)

- Green, Edward C. The Matawai Maroons: An Acculturating Afro American Society, (Ph.D. dissertation, Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America, 1974.) Available through University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Mich., 1974.

- Green, Edward C., "Rum: A Special purpose Money in Matawai Society", Social and Economic Studies, Vol.25, No.4, pp. 411 417, 1976.

- Green, Edward C., "Matawai Lineage Fission", Bijdragen Tot de Taal Land En Volkenkunde (Contributions to Linguistics and Ethnology, the Netherlands), Vol.133, pp. 136 154, 1977.

- Green, Edward C., "Social Control in Tribal Afro America", Anthropological Quarterly, Vol 50(3) pp. 107 116, 1977.

- Green, Edward C., "Winti and Christianity: A Study of Religious Change", Ethnohistory, Vol.25, No.3, pp. 251 276, 1978;

- Herskovits, Melville J., and Frances S. Herskovits. 1934. Rebel Destiny: Among the Bush Negroes of Dutch Guiana. New York and London: McGraw-Hill.

- Kambel, Ellen-Rose, and Fergus MacKay. 1999. The Rights of Indigenous People and Maroons in Suriname. Copenhagen, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs.

- Migge, Bettina (ed.). 2007. "Substrate Influence in the Creoles of Suriname." Special issue of Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 22(1).

- Polimé, T. S., and H. U. E. Thoden van Velzen. 1998. Vluchtelingen, opstandelingen en andere: Bosnegers van Oost-Suriname, 1986-1988. Utrecht: Instituut voor Culturele Antropologie.

- Price, Richard. 1975. Saramaka Social Structure: Analysis of a Maroon Society in Surinam. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Institute of Caribbean Studies.

- Price, Richard. 1983. First-Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Price, Richard. 1983. To Slay the Hydra: Dutch Colonial Perspectives on the Saramaka Wars. Ann Arbor: Karoma.

- Price, Richard. 1990. Alabi's World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Richard Price (ed.). 1996. Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 3rd edition.

- Price, Richard. 2002. "Maroons in Suriname and Guyane: How Many and Where." New West Indian Guide 76:81-88.

- Price, Richard. 2008. Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Price, Richard. 2011. Rainforst Warriors: Human Rights on Trial. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Price, Richard, and Sally Price. 1977. "Music from Saramaka: A Dynamic Afro American Tradition", Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Folkways Recording FE 4225.

- Price, Richard, and Sally Price. 1991. Two Evenings in Saramaka. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Price, Richard, and Sally Price. 2003. Les Marrons. Châteauneuf-le-Rouge: Vents d'ailleurs.

- Price, Richard, and Sally Price. 2003. The Root of Roots, Or, How Afro-American Anthropology Got Its Start. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

- Price, Sally. 1984. Co-Wives and Calabashes. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Price, Sally, and Richard Price. 1999. Maroon Arts: Cultural Vitality in the African Diaspora. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Thoden van Velzen, H.U.E., and W. van Wetering. 1988. The Great Father and the Danger: Religious Cults, Material Forces, and Collective Fantasies in the World of the Suriname Maroons. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Thoden van Velzen, H.U.E., and W. van Wetering. 2004. In the Shadow of the Oracle: Religion as Politics in a Suriname Maroon Society. Long Grove: Waveland.

- Westoll, Andrew. 2008. The Riverbones: Stumbling After Eden in the Jungles of Suriname. Toronto: Emblem Editions.

Notes

- ^ José Juan Arrom, "Cimarrón: Apuntes sobre sus primeras documentaciones y su probable origen", in Cimarrón, José Juan Arrom and Manuel A. García Arévalo, Santo Domingo, Fundación García Arévalo, pp. 13-30 (1986)

- ^ Richard Price (ed.), Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 3rd edition, 1996, pp. xi-xii.

- ^ Richard Price, "Maroons in Suriname and Guyane: How Many and Where." New West Indian Guide 76(2002):81-88.

- ^ Richard Price and Sally Price, Les Marrons, Châteauneuf-le-Rouge, Vents d'ailleurs, 2003.

- ^ Richard Price, Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008, p. 436.

- ^ Migge, Bettina (ed.), "Substrate Influence in the Creoles of Suriname", Special issue of Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 22(1), 2007.

- ^ Richard Price, First-Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People, Baltimore and London, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Richard Price, To Slay the Hydra: Dutch Colonial Perspectives on the Saramaka Wars. Ann Arbor Karoma, 1983. Richard Price, Alabi's World, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990.

- ^ Polimé, T. S. and H. U. E. Thoden van Velzen, Vluchtelingen, opstandelingen en andere: Bosnegers van Oost-Suriname, 1986-1988, Utrecht, Instituut voor Culturele Antropologie, 1998.

- ^ Ellen-Rose Kambel and Fergus MacKay, The Rights of Indigenous People and Maroons in Suriname, Copenhagen, International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs, 1999.

- ^ Andrew Westoll, The Riverbones: Stumbling After Eden in the Jungles of Suriname, Toronto, Emblem Editions, 2008.

- ^ Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname, Judgment of November 28, 2007, Inter-American Court of Human Rights (La Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos), accessed 21 May 2009

- ^ Richard Price, Rainforest Warriors: Human Rights on Trial, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011; "Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname", Inter-American Court for Human Rights (ser. C). No. 172 (28 November 2007); Lisl Brunner, "The Rise of Peoples’ Rights in the Americas: The Saramaka People Decision of the Inter-American Court on Human Rights", Chinese Journal of International Law, 7 (2008):699-711.

- ^ Richard Price, Saramaka Social Structure, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, Institute of Caribbean Studies, 1975.

- ^ Sally Price and Richard Price, Maroon Arts, Boston, Beacon Press, 1999.

- ^ For examples of popular songs, work songs, finger piano pieces, children's riddles, drum language on the apínti talking drum, and more, see Richard Price and Sally Price, "Music from Saramaka: A Dynamic Afro American Tradition", Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Folkways Recording FE 4225, 1977.

- ^ Sally Price, Co-wives and Calabashes, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, 1984.

- ^ Richard Price, Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

- ^ Richard and Sally Price, Two Evenings in Saramaka, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1991.

- ^ Melville J Herskovits and Frances S. Herskovits, Rebel Destiny: Among the Bush Negroes of Dutch Guiana, New York and London, McGraw-Hill, 1934; Richard Price and Sally Price, The Root of Roots, Or, How Afro-American Anthropology Got Its Start, Chicago, Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

- ^ H.U.E. Thoden van Velzen and W. van Wetering, The Great Father and the Danger: Religious Cults, Material Forces, and Collective Fantasies in the World of the Suriname Maroons, Dordrecht, Foris, 1988; H.U.E. Thoden van Velzen and W. van Wetering, In the Shadow of the Oracle: Religion as Politics in a Suriname Maroon Society, Long Grove, Waveland, 2004.

Categories:- Ethnic groups in Suriname

- Maroons

- Indigenous land rights

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.