- History of martial arts

-

The Boxer of Quirinal resting after contest (Bronze sculpture, 3rd century BC)

The Boxer of Quirinal resting after contest (Bronze sculpture, 3rd century BC)

The early history of martial arts is difficult to reconstruct. Inherent patterns of human aggression which inspire practice of mock combat (in particular wrestling) and optimization of serious close combat as cultural universals are doubtlessly inherited from the pre-human stage, and were made into an "art" from the earliest emergence of that concept. Indeed, many universals of martial art are fixed by the specifics of human physiology and not dependent on a specific tradition or era.

Specific martial arts traditions become identifiable in Ancient Kemet, with fighting systems such as Nuba Wrestling, or Classical Antiquity, with disciplines such as Gladiatorial combat, Greek wrestling, Pankration, or those described in the Indian epics or the Spring and Autumn Annals of China. In modern times, these traditional roots were often used to legitimize invented traditions which were in fact quite new.

Contents

Early history

detail of the wrestling fresco in tomb 15 at Beni Hasan.

detail of the wrestling fresco in tomb 15 at Beni Hasan.

The earliest evidence for specifics of martial arts as practiced in the past comes from depictions of fights, both in figurative art and in early literature, besides analysis of archaeological evidence, especially of weaponry.

Wrestling is a human universal, and is also observed in other great apes, especially in juveniles. The spear has been in use since the Lower Paleolithic and retained its central importance well into the 2nd millennium AD. The bow appears in the Upper Paleolithic and is likewise only gradually replaced by the crossbow, and eventually firearms, in the Common Era. True bladed weapons appear in the Neolithic with the stone axe, and diversify in shape in the course of the Bronze Age (khopesh/kopis, sword, dagger)

One very early example is the depiction of wrestling techniques in a tomb of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt at Beni Hasan (c. 2000 BC). An even earlier depiction of Bronze Age military equipment is depicted on the "war panel" of the Standard of Ur (c. 2600 BC), which does however not show actual combat. A third depiction of early martial arts is a Cycladic firgurine from the Cycladic II Period, (about 2800–2300 BC) which shows a Cycladic warrior drawing a dagger with his left hand and blocking with his right. It can be seen in the Museum of Cycladic Art, Athens, Greece.

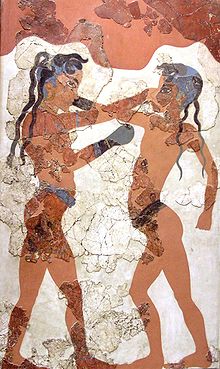

Literary descriptions of combat begin in the 2nd millennium BC, with cursory mention of weaponry and combat in texts like the Gilgamesh epic or the Rigveda. Detailed description of Late Bronze Age to Early Iron Age hand-to-hand combat with spear, sword and shield are found in the Iliad (c. 8th century BC). Pictorial representations of fist fighting in Minoan civilization date to the 2nd millennium BC.

Asia

Further information: Asian martial arts (origins) and Modern history of East Asian martial artsChina

Main article: History of Chinese martial artsAntiquity (Zhou to Jin)

A hand-to-hand combat theory, including the integration of notions of "hard" and "soft" techniques, is expounded in the story of the Maiden of Yue in the Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue (5th c. BC).[1]

The Han History Bibliographies record that, by the Former Han (206 BC – 8 AD), there was a distinction between no-holds-barred weaponless fighting, which it calls shǒubó (手搏), for which "how-to" manuals had already been written, and sportive wrestling, then known as juélì or jiǎolì (角力).

Wrestling is also documented in the Shǐ Jì, Records of the Grand Historian, written by Sima Qian (c. 100 BC).[2] Jiǎolì is also mentioned in the Classic of Rites (1st c. BC).[3]

In the first century, "Six Chapters of Hand Fighting", were included in the Han Shu (history of the Former Han Dynasty) written by Pan Ku. The Five Animals concept in Chinese martial arts is attributed to Hua Tuo, a third-century physician.[4]

Middle Ages

In the Tang Dynasty, descriptions of sword dances were immortalized in poems by Li Bai and Du Fu. In the Song and Yuan dynasties, xiangpu (the earliest form of sumo) contests were sponsored by the imperial courts.

With regards to the Shaolin style of martial arts, the oldest evidence of Shaolin participation in combat is a stele from 728 AD that attests to two occasions: a defense of the Shaolin Monastery from bandits around 610 AD, and their subsequent role in the defeat of Wang Shichong at the Battle of Hulao in 621 AD From the 8th to the 15th centuries, there are no extant documents that provide evidence of Shaolin participation in combat.

Late Ming

The modern concepts of wushu emerge by the late Ming to early Qing dynasties (16th to 17th centuries).[5]

Between the 16th and 17th centuries there are at least forty extant sources which provided evidence that, not only did monks of Shaolin practice martial arts, but martial practice had become such an integral element of Shaolin monastic life that the monks felt the need to justify it by creating new Buddhist lore.[6]

References of martial arts practice in Shaolin appear in various literary genres of the late Ming: the epitaphs of Shaolin warrior monks, martial-arts manuals, military encyclopedias, historical writings, travelogues, fiction, and even poetry. However these sources do not point out to any specific style originated in Shaolin.[7] These sources, in contrast to those from the Tang period, refer to Shaolin methods of armed combat. This include the forte of

Shaolin monks and for which they had become famous — the staff (Gun); General Qi Jiguang included these techniques in his book, Treatise of Effective Discipline. Despite the fact that others criticized the techniques, Ming General Yu Dayou visited the Temple and was not impressed with what he saw, he recruited three monks who he would train for few years after which they returned to the temple to train his fellow monks.[8]

India

Main article: Indian martial artsFurther information: Origins of Kalarippayattu and Dravidian martial artsThe classical Sanskrit epics contain accounts of combat, describing warriors such as Bhima. The Mahabharata describes a prolonged battle between Arjuna and Karna using bows, swords, trees and rocks, and fists.[9] Another unarmed battle in the Mahabharata describes two fighters boxing with clenched fists and fighting with kicks, finger strikes, knee strikes and headbutts.[10] Other boxing fights are also described in Mahabharata and Ramayana.[11]

The word "kalari" is mentioned in Sangam literature from the 2nd century BC. The Akananuru and Purananuru describe the martial arts of ancient Tamilakkam, including forms of one-to-one combat, and the use of spears, swords, shields, bows and silambam.[dubious ][12]

A martial art called Vajra Mushti is mentioned in Indian sources of the early centuries AD. Indian military accounts of the Gupta Empire (c. 240-480) identified over 130 different classes of weapons.[citation needed] The Kama Sutra written by Vātsyāyana at the time suggested that women should regularly "practice with sword, single-stick, quarter-staff, and bow and arrow."

Around 630, King Narasimhavarman of the Pallava dynasty commissioned dozens of granite sculptures showing unarmed fighters disarming armed opponents. These may have shown an early form of Varma Adi, a martial art that allowed kicking, kneeing, elbowing, and punching to the head and chest, but prohibited blows below the waist.

Martial arts were not exclusive to the Kshatriya warrior caste, though they used the arts more extensively. The 8th century text Kuvalaymala by Udyotanasuri recorded martial arts being taught at salad and ghatika educational institutions, where Brahmin students from throughout the subcontinent (particularly from South India, Rajasthan and Bengal) "were learning and practicing archery, fighting with sword and shield, with daggers, sticks, lances, and with fists, and in duels (niuddham)."

The earliest extant manual of Indian marital arts is contained as chapters 248 to 251 in the Agni Purana (c. 8th–11th century), giving an account of dhanurveda in a total of 104 shlokas.[13][14][15] These verses describe how to improve a warrior's individual prowess and kill enemies using various different methods in warfare, whether a warrior went to war in chariots, elephants, horses, or on foot. Foot methods were subdivided into armed combat and unarmed combat.[16] The former included the bow and arrow, the sword, spear, noose, armour, iron dart, club, battle axe, discus, and the trident. The latter included wrestling, knee strikes, and punching and kicking methods.

The earliest description of wrestling techniques in Sanskrit literature is found in the Malla Purana (13th century).

Japan

Main article: KoryūKoryū (古流) is a Japanese word that is used in association with the ancient Japanese martial arts. This word literally translates as "old school" or "traditional school". Koryū is a general term for Japanese schools of martial arts that predate the Meiji Restoration (the period from 1866 to 1869 which sparked major socio-political changes and led to the modernization of Japan). While there is no "official" cutoff date, the dates most commonly used are either 1868, the first year of the Meiji period, or 1876, when the Haitōrei edict banning the wearing of swords was pronounced.[17]

The Japanese Book of Five Rings dates to 1664.

Korea

The Korean Muyejebo dates to 1598, the Muyedobotongji dates to 1790.

West and Central Asia

The traditional Persian style of grappling was known as Koshti, with the and physical exercise and schooled sport known as Varzesh-e Pahlavani. It was said[18] to be traceable back to Arsacid Parthian times (132 BC - 226 AD), and is still widely practiced today in the region. Following the development of Sufi Islam in the 8th century AD, Varzesh-e Pahlavani absorbed philosophical and spiritual components from that religion. Other historical grappling styles from the region include Turkic forms such as Kurash, Köräş and Yağlı güreş.

Europe

Main article: Historical European martial artsFurther information: History of fencing and Ancient Greek BoxingAntiquity

Further information: Ancient warfareEuropean martial arts becomes tangible in Greek antiquity with Pankration and other martially oriented disciplines of the Ancient Olympics. Boxing became Olympic in Greece as early as 688 BC. Detailed depictions of wrestling techniques are preserved in vase paintings of the Classical period. Homer's Iliad has a number of detailed descriptions of single combat with spear, sword and shield.

Gladiatorial combat appears to have Etruscan roots, and is documented in Rome from the 260s BC.

The papyrus fragment known as P.Oxy. III 466 (2nd century) is the earliest extant literary description of wrestling techniques.

In Sardegna (Italy), in the Bronze Age was practiced a fight style called "Istrumpa". It's proved by the finding of a little bronze statue (called "Bronzetto dei lottatori" or fighter's bronze), where two fighters are on the ground.

Middle Ages

Pictorial sources of medieval combat include the Bayeux tapestry (11th century), the Morgan Bible (13th century). The Icelandic sagas contain many realistic descriptions of Viking Age combat.

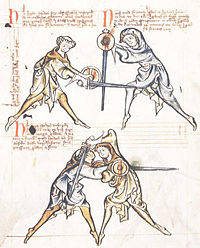

The earliest extant dedicated martial arts manual is the MS I.33 (c. 1300), detailing sword and buckler combat, compiled in a Franconian monastery. The manuscript consist of 64 images with Latin commentary, interspersed with technical vocabulary in German. While there are earlier manuals of wrestling techniques, I.33 is the earliest known manual dedicated to teaching armed single combat.

Wrestling throughout the Middle Ages was practiced by all social strata. Jousting and the tournament were popular martial arts practiced by nobility throughout the High and Late Middle Ages.

The Late Middle Ages see the appearance of elaborate fencing systems, such as the German or Italian schools.

In the Late Middle Ages, fencing schools (Fechtschulen) for the new bourgeois class become popular, increasing the demand for professional instructors (fencing masters, Fechtmeister). The martial arts techniques taught in this period is preserved in a number of 15th century Fechtbücher.

Renaissance to Early Modern period

Further information: Early Modern warfareThe late medieval German school survives into the German Renaissance, and there are a number of printed 16th-century manuals (notably the one by Joachim Meyer, 1570). But by the 17th century, the German school declines in favour of the Italian Dardi school, reflecting the transition to rapier fencing in the upper classes. Wrestling comes to be seen as an ignoble pursuit proper for the lower classes and until its 19th-century revival as a modern sport becomes restricted to folk wrestling.

In the Baroque period, fashion shifts from Italian to Spanish masters, and their elaborate systems of Destreza. In the mid-18th century, in keeping with he general Rococo fashion, French masters rise to international prominence, introducing the foil, and much of the terminology still current in modern sports fencing.

There are also a number of Early Modern fencing masters of note in England, such as George Silver and Joseph Swetnam.

Academic fencing takes its origin in the Middle Ages, and is subject to the changes of fencing fashion throughout the Early Modern period. It establishes itself as the separate style of Mensur fencing in the 18th

Modern history (1800 to present)

Further information: Modern history of East Asian martial artsThe systems of Japanese martial arts that post-date the Meiji Restoration are known as gendai budō. The most well known of these arts include judo, kendo, some schools of iaidō, and aikido. The Western interest in East Asian Martial arts dates back to the late 19th century, due to the increase in trade between America with China and Japan. European martial arts before that time was focussed on the duelling sword among the upper classes on one hand, and various styles of folk wrestling among the lower classes on the other.

Edward William Barton-Wright, a railway engineer who had studied Jujutsu while working in Japan between 1894–97, was the first man known to have taught Asian martial arts in Europe. He also founded an eclectic martial arts style named Bartitsu which combined jujutsu, judo, boxing, savate and stick fighting. Also during the late 19th century and early 20th century, catch wrestling contests became immensely popular in Europe.

The development of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu from the early 20th century is a good example of the worldwide cross-pollination and syncretism of martial arts traditions.

During pre-war and World War Two shows the practicality of martial arts in the modern world and were used by Japanese, US, Nepalese (Gurkha) commandos as well as Resistance groups, such as in the Philippines, (see Raid at Los Baños) but not so excessively or at all for common soldiers.

The later 1970s and 1980s witnessed an increased media interest in the martial arts, thanks in part to Asian and Hollywood martial arts movies and very popular television shows like "Kung Fu", "Martial Law" and "The Green Hornet" that incorporated martial arts moments or themes. Following Bruce Lee, both Jackie Chan and Jet Li are prominent movie figures who have been responsible for promoting Chinese martial arts in recent years.

References

- ^ trans. and ed. Zhang Jue (1994), pp. 367-370, cited after Hennin (1999) p. 321 and note 8.

- ^ Henning, Stanley E. (Fall 1999). "Academia Encounters the Chinese Martial arts". China Review International 6 (2): 319–332. ISSN 1069-5834 [1]

- ^ Classic of Rites. Chapter 6, Yuèlìng. Line 108.

- ^ Dingbo. Wu, Patrick D. Murphy (1994), "Handbook of Chinese Popular Culture", Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-27808-3

- ^ China Sportlight Series (1986) "Sports and Games in Ancient China". New World Press, ISBN 0-8351-1534-8.

- ^ Shahar, Meir (2000). "Epigraphy, Buddhist Historiography, and Fighting Monks: The Case of The Shaolin Monastery". Asia Major Third Series 13 (2): 15–36.

- ^ Shahar, Meir (December 2001). "Ming-Period Evidence of Shaolin Martial Practice". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 61 (2): 359–413. ISSN 0073-0548.

- ^ Henning, Stanley (1999). "Martial arts Myths of Shaolin Monastery, Part I: The Giant with the Flaming Staff". Journal of the Chenstyle Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii 5 (1), Shahar, Meir (2007), The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion and the Chinese Martial arts", Honolulu: The University of Hawai'i Press

- ^ Zarrilli, Phillip B. A South Indian Martial Art and the Yoga and Ayurvedic Paradigms. University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- ^ Section XIII: Samayapalana Parva, Book 4: Virata Parva, Mahabharata.

- ^ Shamya Dasgupta (June–September 2004). "An Inheritance from the British: The Indian Boxing Story", Routledge 21 (3), p. 433-451.

- ^ Suresh, P. R. (2005). Kalari Payatte - The martial art of Kerala.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Zarrilli, Phillip B. (1992). "To Heal and/or To Harm: The Vital Spots (Marmmam/Varmam) in Two South Indian Martial Traditions Part I: Focus on Kerala's Kalarippayattu". Journal of Asian Martial Arts 1 (1). http://www.spa.ex.ac.uk/drama/staff/kalari/healharm.html.

- ^ P. C. Chakravarti (1972). The art of warfare in ancient India. Delhi.

- ^ GRETIL etext, based on Rajendralal Mitra, Calcutta : Asiatic Society of Bengal 1870–1879, 3 vols. (Bibliotheca Indica, 65,1-3); AP 248.1-38, 249.1-19, 250.1-13, 251.1-34.

- ^ J. R. Svinth (2002). A Chronological History of the Martial Arts and Combative Sports. Electronic Journals of Martial Arts and Sciences.

- ^ Skoss, Diane (2006-05-09). "A Koryu Primer". Koryu Books. http://www.koryu.com/koryu.html. Retrieved 2007-01-01.

- ^ Nekoogar, Farzad (1996). Traditional Iranian Martial Arts (Varzesh-e Pahlavani). pahlvani.com: Menlo Park. Accessed: 2007-02-08

- Michael B. Poliakoff, Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture Sports and History Series, Yale University Press (1987).

See also

- Martial arts timeline

- History of sport

- History of archery

- History of warfare

- Folk wrestling

- Weapon dance

- History of wrestling

Categories:- Historical martial arts

- History of sports

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.