- Daniel Sickles

-

Daniel Edgar Sickles

Major General Sickles circa 1862 Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from New York's 10th districtIn office

March 4, 1893 – March 3, 1895Preceded by William Bourke Cockran Succeeded by Amos J. Cummings Member of the U.S. House of Representatives

from New York's 3rd districtIn office

March 4, 1857 – March 3, 1861Preceded by Guy R. Pelton Succeeded by Benjamin Wood United States Minister to Spain In office

May 15, 1869 – January 31, 1874Preceded by John P. Hale Succeeded by Caleb Cushing Personal details Born October 20, 1819

New York City, New YorkDied May 3, 1914 (aged 94)

New York City, New YorkResting place Arlington National Cemetery Political party Democratic Spouse(s) Teresa Bagioli Sickles (m. 1852–1867)

Carmina Creagh (m. 1871–1914)Military service Nickname(s) "Devil Dan"[1] Allegiance United States of America

UnionService/branch United States Army

Union ArmyYears of service 1861–1869 Rank  Major General

Major GeneralCommands III Corps Battles/wars American Civil War Awards Medal of Honor Daniel Edgar Sickles (October 20, 1819 – May 3, 1914) was a colorful and controversial American politician, Union general in the American Civil War, and diplomat.

As an antebellum New York politician, Sickles was involved in a number of public scandals, most notably the killing of his wife's lover, Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key.[2] He was acquitted with the first use of temporary insanity as a legal defense in U.S. history. He became one of the most prominent political generals of the Civil War. At the Battle of Gettysburg, he insubordinately moved his III Corps to a position in which it was virtually destroyed, an action that continues to generate controversy. His combat career ended at Gettysburg when his leg was struck by cannon fire.

After the war, Sickles commanded military districts during Reconstruction, served as U.S. Minister to Spain, and eventually returned to the U.S. Congress, where he made important legislative contributions to the preservation of the Gettysburg Battlefield.

Contents

Early life and politics

Sickles was born in New York City to Susan Marsh Sickles and George Garrett Sickles, a patent lawyer and politician.[3] (His year of birth is sometimes given as 1825, and, in fact, Sickles himself was known to have claimed as such. Historians speculate that Sickles deliberately chose to appear younger when he married a woman half his age.) He learned the printer's trade and studied at the University of the City of New York (now New York University). He studied law in the office of Benjamin Butler, was admitted to the bar in 1846, and was a member of the New York Assembly in 1843.[3]

In 1852, he married Teresa Bagioli against the wishes of both families—he was 33, she only 15, although she was sophisticated for her age, speaking five languages. In 1853 he became corporation counsel of New York City, but resigned soon afterward to become secretary of the U.S. legation in London, under James Buchanan, by appointment of President Franklin Pierce. He returned to America in 1855, was a member of the Senate of New York State from 1856 to 1857, and, from 1857 to 1861, was a Democratic representative in the United States Congress (the 35th and 36th United States Congresses).

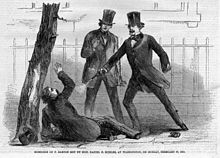

Murder of Key

Sickles's career was replete with personal scandals. He was censured by the New York State Assembly for escorting a known prostitute, Fanny White, into its chambers. He also reportedly took her to England, leaving his pregnant wife at home, and presented White to Queen Victoria, using as her alias the surname of a New York political opponent.[3] In 1859, in Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House, Sickles shot and killed the district attorney of the District of Columbia[4] Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key, whom Sickles had discovered was having an affair with his young wife.[2][5]

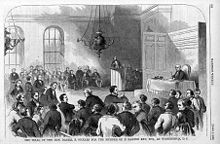

Trial

"You are here to fix the price of the marriage bed!", roared Associate Defense Attorney John Graham, in a speech so packed with quotations from Othello, Judaic history and Roman law that it lasted two days and later appeared as a book.

Sickles surrendered at Attorney General Jeremiah Black's house, a few blocks away on Franklin Square, and confessed to the murder. After a visit to his home, accompanied by a constable, Sickles was taken to jail. He was able to receive visitors, and so many came that he was granted the use of the head jailer's apartment to receive them.[7] This was one of several odd features of his confinement. He was also allowed to retain his personal weapon, unusual even for the time. The press reported heavy visitor traffic, including many representatives, senators, and other leading members of Washington society. President James Buchanan sent Sickles a personal note.

Most painful for Sickles, according to Harper's Magazine, were the visits of his wife's mother and her clergyman. Both told him that Teresa was distracted with grief, shame, and sorrow, and that the loss of her wedding ring (which Sickles had taken on visiting his home) was more than Teresa could bear.

Sickles was charged with murder. He secured several leading politicians as his defense attorneys, among them Edwin M. Stanton, later to become Secretary of War, and Chief Counsel James T. Brady, like Sickles a product of Tammany Hall. In a historic strategy, Sickles pled insanity—the first use of a temporary insanity defense in the United States.[8] Before the jury, Stanton argued that Sickles had been driven insane by his wife's infidelity, and thus was out of his mind when he shot Key. The papers soon trumpeted that Sickles was a hero for saving all the ladies of Washington from this rogue named Key.[9]

The graphic confession that Sickles had obtained from Teresa on Saturday proved pivotal. It was ruled inadmissible in court, but, leaked by Sickles to the press, was printed in the newspapers in full. The defense strategy ensured that the trial was the main topic of conversations in Washington for weeks, and the extensive coverage of national papers was sympathetic to Sickles.[10] In the courtroom, the strategy brought drama, controversy, and, ultimately, an acquittal for Sickles.

Sickles then publicly forgave Teresa, and "withdrew" briefly from public life, although he did not resign from Congress. The public was apparently more outraged by Sickles' forgiveness and reconciliation with his wife, whom he had publicly branded a harlot and adulteress, than by the murder and his unorthodox acquittal.[11]

Civil War

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Sickles desired to repair his public image and was active in raising volunteers in New York. He was appointed colonel of one of the four regiments he organized. He was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers in September 1861, becoming one of the most famous political generals in the Union Army. In March 1862, he was forced to relinquish his command when the U.S. Congress refused to confirm his commission, but he worked diligently to lobby among his Washington political contacts and reclaimed both his rank and his command on May 24, 1862, in time to rejoin the Army in the Peninsula Campaign.[3] Because of this interruption, he missed his brigade's significant actions at the Battle of Williamsburg. Despite his complete lack of previous military experience, he did a competent job commanding the "Excelsior Brigade" of the Army of the Potomac in the Battle of Seven Pines and the Seven Days Battles. He was absent for the Second Battle of Bull Run,[5] having used his political influences to obtain leave to go to New York City to recruit new troops. He also missed the Battle of Antietam because the III Corps, to which he was assigned as a division commander, was stationed on the lower Potomac, protecting the capital.

Sickles was a close ally of Major General Joseph Hooker, who was his original division commander and eventually commanded the Army of the Potomac. Both men had notorious reputations as political climbers and as hard-drinking ladies' men. Accounts at the time compared their army headquarters to a rowdy bar and bordello.

Sickles was promoted to major general on November 29, 1862, just before the Battle of Fredericksburg, in which his division was in reserve. Hooker, now commanding the Army of the Potomac, gave Sickles command of the III Corps in February 1863, a controversial move in the army because he became the only corps commander without a West Point education. His energy and ability were conspicuous in the Battle of Chancellorsville. He aggressively recommended pursuing troops he saw in his sector on May 2, 1863. Sickles thought the Confederates were retreating, but these turned out to be elements of Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson's corps, stealthily marching around the Union flank. He also vigorously opposed Hooker's orders moving him off good defensive terrain in Hazel Grove. In both of these cases, it is easy to imagine the disastrous battle turning out very differently for the Union if Hooker had heeded his advice.[citation needed]

Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg marked the most famous incident, and the effective end, of Sickles' military career. On July 2, 1863, Army of the Potomac commander Major General George G. Meade ordered Sickles' corps to take up defensive positions on the southern end of Cemetery Ridge, anchored in the north to the II Corps and to the south, the hill known as Little Round Top. Sickles was unhappy to see a slightly higher terrain feature to his front, the "Peach Orchard". Perhaps remembering the beating his corps had taken from Confederate artillery at Hazel Grove during the Battle of Chancellorsville, he violated orders by marching his corps almost a mile in front of Cemetery Ridge. This had two effects: it greatly diluted the concentrated defensive posture of his corps by stretching it too thin, and it created a salient that could be bombarded and attacked from multiple sides. Meade rode out and confronted Sickles about his insubordination, but it was too late. The Confederate assault by Lieutenant General James Longstreet's corps, primarily by the division of Major General Lafayette McLaws, smashed the III Corps and rendered it useless for further combat. Gettysburg campaign historian Edwin B. Coddington assigns "much of the blame for the near disaster" in the center of the Union line to Sickles.[12] Stephen W. Sears wrote that "Dan Sickles, in not obeying Meade's explicit orders, risked both his Third Corps and the army's defensive plan on July 2.[13] However, Sickles' maneuver has recently been credited by John Keegan with blunting the whole Confederate offensive that was intended to cause the collapse of the Union line.[14] Similarly, James M. McPherson wrote that "Sickles's unwise move may have unwittingly foiled Lee's hopes."[15]

During the height of the Confederate attack, Sickles fell victim to a cannonball that mangled his right leg. Carried by stretcher to an aid station, he bravely attempted to raise his soldiers' spirits by grinning and puffing on a cigar along the way. His leg was amputated that afternoon. He insisted on being transported back to Washington, D.C., which he reached on July 4, 1863, bringing some of the first news of the great Union victory, and starting a public relations campaign to ensure his version of the battle prevailed.

Sickles had recent knowledge of a new directive from the Army Surgeon General to collect and forward "specimens of morbid anatomy ... together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed" to the newly founded Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C. He preserved the bones from his leg and donated them to the museum in a small coffin-shaped box, along with a visiting card marked, "With the compliments of Major General D.E.S." For several years thereafter, he reportedly visited the limb on the anniversary of the amputation. The museum, now known as the National Museum of Health and Medicine, features the artifact on display still today. (Other Civil War-era specimens of note on display include the hip of General Henry Barnum, and in the collection but not on display include the vertebrae from assassin John Wilkes Booth and President James A. Garfield.)

Sickles was not court-martialed for insubordination after Gettysburg because he had been wounded, and it was assumed he would stay out of trouble. Furthermore, he was a powerful, politically connected man who would not accept being disciplined without protest and retribution.

Sickles ran a vicious campaign against General Meade's character after the Civil War. Sickles felt that Meade had wronged him at Gettysburg and that credit for winning the battle belonged to him. In anonymous newspaper articles and in testimony before a congressional committee, Sickles maintained that Meade had secretly planned to retreat from Gettysburg on the first day. While his movement away from Cemetery Ridge may have violated orders, Sickles always asserted that it was the correct move because it disrupted the Confederate attack, redirecting its thrust, effectively shielding their real objectives, Cemetery Ridge and Cemetery Hill. Sickles' redeployment did in fact take Confederate commanders by surprise, and historians have argued about the real ramifications ever since.

Sickles eventually received the Medal of Honor for his actions, although it took him 34 years to get it. The official citation that accompanied his medal recorded that Sickles "displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field, vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded."[16]

Postbellum career

Despite his one-legged disability, Sickles remained in the army until the end of the war and was disgusted that Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant would not allow him to return to a combat command. In 1867, he received appointments as brevet brigadier general and major general in the regular army for his services at Fredericksburg and Gettysburg, respectively.

Soon after the close of the Civil War, in 1865, he was sent on a confidential mission to Colombia (the "special mission to the South American Republics") to secure its compliance with a treaty agreement of 1846 permitting the United States to convey troops across the Isthmus of Panama. From 1865 to 1867, he commanded the Department of South Carolina, the Department of the Carolinas, the Department of the South, and the Second Military District. In 1866, he was appointed colonel of the 42nd U.S. Infantry (Veteran Reserve Corps), and in 1869 he was retired with the rank of major general.

Sickles served as U.S. Minister to Spain from 1869 to 1874, after the Senate failed to confirm Henry Shelton Sanford to the post, and took part in the negotiations growing out of the Virginius Affair. His inaccurate and emotional messages to Washington promoted war, until he was overruled by Secretary of State Hamilton Fish and the war scare died out.[17]

Sickles maintained his reputation as a ladies' man in the Spanish royal court and was rumored to have had an affair with the deposed Queen Isabella II. Following the death of Teresa in 1867, in 1871, he married Senorita Carmina Creagh, the daughter of Chevalier de Creagh of Madrid, a Spanish Councillor of State. They had two children.

Sickles was president of the New York State Board of Civil Service Commissioners from 1888 to 1889, sheriff of New York in 1890, and again a representative in the 53rd Congress from 1893 to 1895. For most of his postwar life, he was the chairman of the New York Monuments Commission, but he was forced out when $27,000 was found to have been embezzled.[18]

He had an important part in efforts to preserve the Gettysburg Battlefield, sponsoring legislation to form the Gettysburg National Military Park, buy up private lands, and erect monuments. One of his contributions was procuring the original fencing used on East Cemetery Hill to mark the park's borders. This fencing came directly from Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C. (site of the Key shooting).[19][20] Of the principal senior generals who fought at Gettysburg, virtually all, with the conspicuous exception of Sickles, have been memorialized with statues at Gettysburg. When asked why there was no memorial to him, Sickles supposedly said, "The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles." However, there was, in fact, a memorial commissioned to include a bust of Sickles, the monument to the New York Excelsior Brigade. It was rumored that the money appropriated for the bust was stolen by Sickles himself; the monument is displayed in the Peach Orchard with a figure of an eagle instead of Sickles' likeness.

Death

Sickles lived out the remainder of his life in New York City, dying on May 3, 1914. His funeral was held at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Manhattan on May 8, 1914. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[16][21]

In popular media

Sickles appears prominently in the books Gettysburg and Grant Comes East, the first two books of the alternate history Civil War trilogy by Newt Gingrich and William R. Forstchen.

Medal of Honor citation

- Rank and organization: Major General, U.S. Volunteers

- Place and Date: At Gettysburg, Pa., July 2, 1863.

- Entered Service At: New York, N.Y.

- Birth: New York, N.Y.

- Date of Issue: October 30, 1897.

Citation:

- Displayed most conspicuous gallantry on the field vigorously contesting the advance of the enemy and continuing to encourage his troops after being himself severely wounded.[22][23]

See also

- List of American Civil War generals

- List of American Civil War Medal of Honor recipients: Q–S

- List of U.S. political appointments that crossed party lines

Notes

- ^ Devil Dan Sickles' Deadly Salients - America's Civil War magazine, November 1998

- ^ a b "Assassination of Philip Barton Key, by Daniel E. Sickles of New York". Hartford Daily Courant. March 1, 1959. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/courant/access/824716112.html?dids=824716112:824716112&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI&type=historic&date=Mar+01,+1859&author=&pub=Hartford+Courant&desc=Assassination+of+Philip+Barton+Key,+by+Daniel+E.+Sickles+of+New+York&pqatl=google. Retrieved 2010-11-30. "For more than a year there have been floating rumors of improper intimacy between Mr. Key and Mrs. Sickles They have from time to time attended parties, the opera, and rode out together. Mr. Sickles has heard of these reports, but would never credit them until Thursday evening last. On that evening, just as a party was about breaking up at his house, Mr Sickles received among his papers..."

- ^ a b c d Beckman, p. 1784.

- ^ Keneally, p. 66.

- ^ a b Tagg, p. 62.

- ^ "Yankee King of Spain". Time Magazine June 18, 1945. June 18, 1945. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,775961,00.html. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Assumption.edu.

- ^ Stankowski, J. E. (2009). "Temporary Insanity". Wiley Encyclopedia of Forensic Science. doi:10.1002/9780470061589.fsa272.

- ^ Harpers Magazine, March 12, 1859 editorializing about the murder and trial: No sympathy needed.

- ^ Assumption.edu: "Both Harper's Weekly and Leslie's ran images of Sickles in prison. Harper's was the more bathetic. It showed a haggard sufferer, hands clasped as if in prayer, staring upwards. Light illumines his face and the wall immediately behind, but the rest of the cell is in shadows. Its title was 'Hon. Daniel E. Sickles in prison at Washington,' but it might well have been captioned 'More Sinned Against Than Sinning.' In a later issue, the magazine editorialized against what it described as a publicity campaign to create sympathy for the Congressman. ... The New York Times, the city's other major Democratic daily and the New York Herald's chief rival for the ear of the Buchanan administration, editorialized that the homicide in no way unfitted the Congressman for office." The source gives many more such cites.

- ^ Harper's editorial on the verdict, May 7, 1859, in which they reject the insanity defense as essentially a sham and point out the prosecution did not try very hard.

- ^ Coddington, p. 411.

- ^ Sears, p. 507.

- ^ Keegan, p. 195.

- ^ McPherson, p. 657.

- ^ a b Eicher, p. 488.

- ^ Richard H. Bradford, The Virginius Affair(1980)

- ^ "Seeks To Wipe Out Sickles Commission. Fine Arts Federation Would Have a State Art Board Named to Take Its Place". New York Times. December 12, 1912. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F30910FA355E13738DDDAB0994DA415B828DF1D3. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ James Hessler. "Dan Sickles / The Battlefield Preservationist". civilwar.org. http://www.civilwar.org/education/history/on-the-homefront/battlefield-preservation/dan-sickles-the-battlefield.html. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Daniel Edgar Sickles, Major General United States Army / From a contemporary news report:". arlingtoncemetery.net. http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/dsickles.htm. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ "Crowds Bare Heads At Sickles Funeral. Military Cortege Marches Up Fifth Avenue to Services in St. Patrick's Cathedral.". New York Times. May 9, 1914. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70D11F6355D13738DDDA00894DD405B848DF1D3. Retrieved 2010-11-30. "Between lines of watchers who bared their heads as the flag-covered coffin passed, a military funeral procession marched up Fifth Avenue from Ninth Street to St. Patrick's Cathedral yesterday morning. On a gun caisson amid a guard of honor, composed of his old comrades in the civil war, was the body of Major Gen. Daniel E. Sickles, commander of the Third Army Corps and one of the last of the heroes of Gettysburg."

- ^ ""Civil War Medal of Honor citations" (S-Z): Sickles, Daniel E.". AmericanCivilWar.com. http://americancivilwar.com/medal_of_honor8.html. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- ^ ""Medal of Honor website" (M-Z): Sickles, Daniel E.". United States Army Center of Military History. http://www.history.army.mil/html/moh/civwarmz.html. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

References

- Beckman, W. Robert. "Daniel Edgar Sickles." In Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign; a study in command. New York: Scribner's, 1968. ISBN 0-684-84569-5.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Keegan, John. The American Civil War: A Military History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-26343-8.

- Keneally, Thomas. American Scoundrel: The Life of the Notorious Civil War General Dan Sickles. New York: Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2002. ISBN 0-385-50139-0.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era (Oxford History of the United States). New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. ISBN 0-19-503863-0.

- Roberts, Sam; (1992-03-01). "Sex, Politics and Murder on the Potomac". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E0CE4DF133CF932A35750C0A964958260. Retrieved 2008-08-08. Review of The Congressman Who Got Away With Murder, By Nat Brandt.

- Sears, Stephen W. Gettysburg. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2003. ISBN 0-395-86761-4.

- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg, Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Bradford, Richard H. The Virginius Affair. Boulder: Colorado Associated University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-87081-080-4.

- Brandt, Nat. The Congressman Who Got Away With Murder. Syracuse, NY: University of Syracuse Press, 1991. ISBN 0-8156-0251-0.

- Hessler, James A. Sickles at Gettysburg: The Controversial Civil War General Who Committed Murder, Abandoned Little Round Top, and Declared Himself the Hero of Gettysburg. New York: Savas Beatie, 2009. ISBN 978-1-932714-64-7.

External links

- SICKLES, Daniel Edgar at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress Retrieved on 2008-09-30

- "Sickles articles at Arlington National Cemetery site". http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/dsickles.htm. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- "Mr. Lincoln and New York: Daniel Sickles". http://www.mrlincolnandnewyork.org/inside.asp?ID=78&subjectID=3. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- "Sickles's amputated leg bones". http://nmhm.washingtondc.museum/explore/anatifacts/2_sickles.html. Retrieved September 29, 2010. preserved at the National Museum of Health and Medicine

- "Rootsweb Genealogy data used for dates of births/deaths". http://worldconnect.rootsweb.com/cgi-bin/igm.cgi?op=GET&db=cheristephens&id=I3514. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- "Daniel Sickles". Claim to Fame: Medal of Honor recipients. Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=2113. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- "Daniel Sickles". Claim to Fame: Medal of Honor recipients. Find a Grave. http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=7381. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- "Photograph of Daniel Edgar Sickles from the Maine Memory Network". http://www.mainememory.net/bin/Detail?ln=5254. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

Military offices Preceded by

George StonemanCommander of the III Corps (Union Army)

February 5, 1863 - May 29, 1863Succeeded by

David B. BirneyPreceded by

David B. BirneyCommander of the III Corps (Union Army)

June 3, 1863 - July 2, 1863Succeeded by

David B. BirneyUnited States House of Representatives Preceded by

Guy R. PeltonMember of the U.S. House of Representatives

from New York's 3rd congressional district

March 4, 1857 - March 3, 1861Succeeded by

Benjamin WoodPreceded by

William B. CockranMember of the U.S. House of Representatives

from New York's 10th congressional district

March 4, 1893 - March 3, 1895Succeeded by

Andrew J. Campbell

(died before taking office)

Amos J. Cummings

(elected to replace Campbell)Diplomatic posts Preceded by

John P. HaleU.S. Minister to Spain

1869–1874Succeeded by

Caleb CushingCategories:- 1819 births

- 1914 deaths

- People from New York City

- Union Army generals

- United States Army generals

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from New York

- New York State Senators

- New York Democrats

- United States ambassadors to Spain

- Members of the New York State Assembly

- American diplomats

- New York sheriffs

- New York lawyers

- Politicians with physical disabilities

- Army Medal of Honor recipients

- People of New York in the American Civil War

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- American amputees

- People acquitted of murder

- People acquitted by reason of insanity

- Excelsior Brigade

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.